Gary Locke’s career tracks the rise of the U.S. policy of engagement with China, and he remains committed to working with Beijing. The child and grandchild of Chinese immigrants, in 1996 Locke was the first Chinese-American elected governor of Washington. During his two terms, he led trade missions to China, pressing for more exports of Boeing planes and other Washington state products. In 2009, he was President Obama’s pick as Commerce Secretary where again he invited business groups to travel with him on export missions to China. From 2011 to 2014, he was ambassador to China, where his informal manner — and Chinese background — was the source of much discussion on Chinese websites. He is now an attorney at Dorsey & Whitney. This interview is part of Rules of Engagement, a series by Bob Davis, who covered the U.S.-China relationship at The Wall Street Journal starting in the 1990s. In these interviews, Davis asks current and former U.S. officials and policymakers what went right, what went wrong and what comes next.

Illustration by Kate Copeland

Q: You are the child of and grandchild immigrants from China. And a lot of your career seemed to be focused on China. How much do you think your background and upbringing influenced how you looked at your different jobs and how you looked at China?

A: When I was in the state legislature, the issues in front of us were very wide ranging. Especially in the human services area or with legal issues, I tried to bring my sensitivities and knowledge about the day-to-day struggles and aspirations of immigrants into the discussion and analysis. But there was nothing really related directly with China.

When I became governor, we did focus on China in terms of trade missions and helping Washington state producers, farmers and companies sell their products and services to China. Trying to expand markets for Washington state companies meant more jobs for the people of the state and a higher level of income.

I’ve always believed in trade — in two-way trade and fair trade. Just as we want people in other countries to buy products made in America or the state of Washington, we have to be open to buying their products.

You went twice to Taishan [the place in southern China where the paternal side of his family had lived], once before becoming ambassador and once after.

The first trip to Taishan in 1997 was near the end of my first year as governor. It was during our first trade mission. We first stopped off in Japan because at that time there was a great sensitivity about so-called Japan passing — everybody passing over Japan and going straight to China. At that time, Japan was then one of our state’s longest and strongest trading partners. So we could not ignore that relationship.

My siblings joined me halfway through the trip to China, and then my mom and dad joined us at the very end. We all met up in Hong Kong and the next day we went by hydrofoil up the Pearl River back to Taishan, where my father was born. [Taishan is in Guangdong province.]

Taishan is the area from which most of the early Chinese immigrated to the United States to finish the construction of the railroad, to work in the lumber camps, and the gold mines. It was the area that was the source of the immigrants that formed the Chinatowns of San Francisco, Seattle, Vancouver, and New York.

They all spoke the Taishan dialect, which is very different from the Hong Kong dialect and very different from Mandarin. My mom and dad had not been back to the family village in 50 years since their wedding. So, this was an opportunity for the family to really reconnect. We went back to the ancestral home, which was occupied by my dad’s uncle, who was much younger than my dad.

It was like stepping back into the 1800s. They cooked using wood kindling and coal briquettes. People had water that came in using a hand pump in one corner of the living room. They used an outhouse about 75 or 100 yards from the edge of the village. They washed their clothes by hand and had very few electrical appliances. The refrigerator was a little bit bigger than what you might see in a hotel room or a college dormitory.This is a village that’s a mile and a half from a modern city of about several million people.

Later on, in December 2013, I went back as ambassador to the village. By then, my father had passed away, and so we wanted to put his picture on the family altar or shrine. I also brought my kids there because I wanted them to see how grandpa was raised and to appreciate the quality of life and the freedom and the luxuries that we have in America.

I take it the village had changed quite a bit.

It had not really changed even then.

When you were ambassador, your personal style was much remarked upon. You’d go to a Starbucks and order for yourself, that kind of thing. Did you feel your Chinese-American heritage put you in a different kind of category? Did you feel any special burden or responsibility?

Embassy and State Department personnel commented that I had access to more high-ranking Chinese government officials than any other previous ambassador. Of course, when I first went to China, the expectations among the Chinese people were that I would be more sympathetic to the position of the Chinese government. The fact that I do not speak Mandarin quickly reinforced in the minds of the Chinese that I am an American and I represent the U.S. government, the American people, and President Obama, and that I was there to convey American values, concerns, and perspectives.

But I think that my Chinese ancestry gave me a little bit more cachet and provided more openings to discussions with Chinese government officials and other members of Chinese society.

In this interview series, we get to see the arc of U.S.-China relations. When you were governor and Commerce secretary, that was during the height of engagement. When you think today about the trade missions you led, do you think that they accomplished something?

On the trade mission as governor, we were mobbed. People say that I was treated like a rock star. That type of treatment helped give Washington state companies and our issues greater publicity and greater gravitas. That made our trade mission much more successful in helping sell Washington State products from cherries to potato chips and or frozen potatoes.

And Boeing aircraft too, right?

| BIO AT A GLANCE | |

|---|---|

| AGE | 74 |

| BIRTHPLACE | Seattle Washington, USA |

| FORMER POSITIONS |

|

And Boeing airplanes and Washington State apples and so forth.

We also had some issues with the Chinese government over their restrictions on Washington state wheat over some phyto-sanitary conditions [placed on U.S. exports]. Because of my stature and my novelty as a Chinese-American governor, we were able to get those resolved to the benefit of Washington state and to its wheat growers. The same thing happened as Commerce Secretary when I was promoting the opening of a Walmart.

Now, of course, China is viewed as toxic. You see very few of those missions anymore. Do you think governors and Commerce secretaries are making a mistake by not doing what you did in leading trade missions?

Certainly, with the tensions between the United States and China there are now greater restrictions on exports of U.S. products to China, especially in the high-tech area. But there is still a great demand for made-in-USA products and services. There’s a need for products and services that would raise the standard of living for the people of China, while at the same time providing jobs for the people of America. At the Commerce Department, we had this saying: “The more U.S. companies export, the more they produce. The more they produce, the more workers they need.” And that means good paying jobs for the American people.

…there are so many issues facing the world that cannot be solved by the United States alone or by China alone. And the world is expecting and demanding joint collaboration…

Yes, we have very tough relations, and we have tensions with China, from human rights to the Taiwan Straits to intellectual property. But there’s a huge demand for so many things made in the U.S.. So, we need to find a way to acknowledge those differences and those tensions, but at the same time collaborate on things of mutual benefit.

Would you urge Commerce Secretary Raimondo to organize and lead some trade missions as well?

Oh, yes. Very much so, whether it’s in environmental services, medical collaboration, or other joint efforts. Certainly U.S. companies excel in environmental technology, and pollution is a huge problem in China affecting the livelihood of the Chinese people.

Let me flip the question. Critics would say that those missions were naïve. The Chinese didn’t import that much, and the United States gave the impression that all we cared about was making money, while other issues, like human rights and political differences were very secondary. What would you say to that?

There were great expectations about China’s trajectory, in terms of democracy and liberalization of government policies, when it joined the World Trade Organization. A lot of those expectations have not come to fruition. Many of us were disappointed in that.

Why do you think it didn’t work out?

I think people were hoping that exposure to the West and more trade would lead to the introduction of more Western ideas and ideals, and that China, as they joined the world order, would adopt many of these principles and policies. But China has not. In fact, under President Xi Jinping, China has become a lot more authoritarian, and the power of the Communist Party has expanded into the affairs of companies.

Nonetheless there are so many issues facing the world that cannot be solved by the United States alone or by China alone. And the world is expecting and demanding joint collaboration, for example, in climate change. If the United States were to make dramatic reductions in greenhouse gases, but China does very little, then all our sacrifices and all of our efforts will be for naught and vice versa.

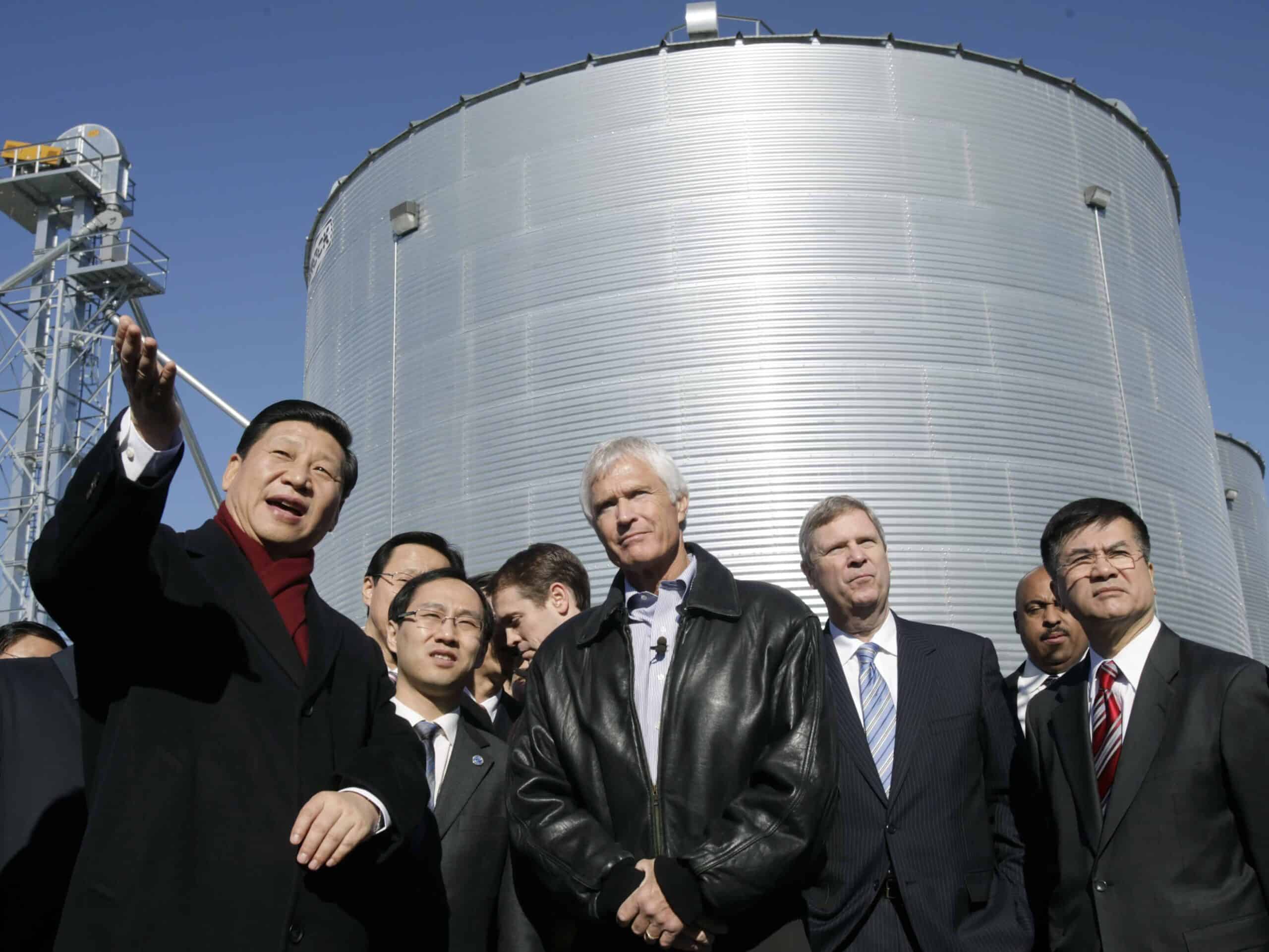

Let’s talk a bit about Xi Jinping. You had a lot of interactions with him aside from being ambassador. You were with him when he toured Iowa as vice president. And after you left as ambassador and he came to Seattle, you were a co-leader of a coordinating group for his visit.

When you were ambassador, after Xi became Party chairman but wasn’t yet president, you were quoted as saying, “I believe everyone inside and outside of China is very hopeful, but only time will tell.” There was a great expectation that Xi was a reformer.

I remember that when he was vice president, he talked about some of the lessons of his father. In one story he recounted, there were some upheavals and the authorities in China were cracking down in a violent way on people who were trying to leave the country or who were protesting social conditions in China. He said that his father said that the government needs to look at their underlying dissatisfaction and not just react to their protestations. The government should try to go deeper and find out what is bothering the Chinese people. So, I think there was hope that he would be a little bit more of a humane leader and really look at the conditions that the people were responding to and try to address them.

Clearly, he has been a much more authoritarian leader, much more confrontational to the United States than expected. Why do you think people misread him?

It’s apparent that the leaders of China are very much concerned about maintaining their power and their grip over the country and maintaining the strength of the Communist Party. You see how much they’re spending on domestic security, censorship, the monitoring of social media, and the crackdown on corruption. It’s all to make sure there’s no internal threat to the power of the Communist Party.

Have you been surprised at how close he’s been to Putin?

It’s been somewhat of a natural evolution. Obviously, there was an estrangement, but they are two communist countries, and they have somewhat of a common history. They also have a great deal of tension and rivalry. I think their closeness is a relationship of convenience right now.

How much do you think the frostiness in U.S.-China relations is because of Xi, or because of Trump, or because of some other reason?

It’s a combination of all of that. The U.S. business community has long been concerned about the trade practices and economic policies of China — the unfair competition that exists. Trump imposed tariffs to try to address some of these issues, but it hasn’t really worked. Americans are actually paying more per household every year according to the New York Fed and the Wall Street Journal because of these tariffs. Of course, President Biden has kept those tariffs in place and has imposed greater restrictions on the sale or exports of technology. It was all for legitimate concerns about our national security.

China is saying, ‘Wow we’re subject to the whims of the political forces in the United States, whether it’s the Congress or the administration, Democrat or Republican. We better double down on some of our policies, like Made in China 2025,’ [an industrial policy plan] where they want to be world-class in many areas of technology.

They’re saying, ‘We better accelerate our efforts to be self-sufficient.’ It’s only going to be a matter of time before China is able to make their own machines and design and manufacture their own chips. So, I see somewhat of an acceleration of decoupling going on.

It sounds like you think the U.S. is going too far.

No. I think we have to protect our national security. We need to be sure that our technology is not helping to advance their military.

I’m just saying, China will eventually produce what they need. We may be delaying them. It could be 10 years, eight years, 15 years, I don’t know. Perhaps they will always lag America by a few years. But they will eventually develop the technology to make many of these advanced semiconductors and devise the machinery to make them themselves.

When you were ambassador to China, the U.S announced the pivot to Asia. That didn’t seem to work very well. It seemed to be more symbol than substance. Why didn’t the pivot seem to do very much?

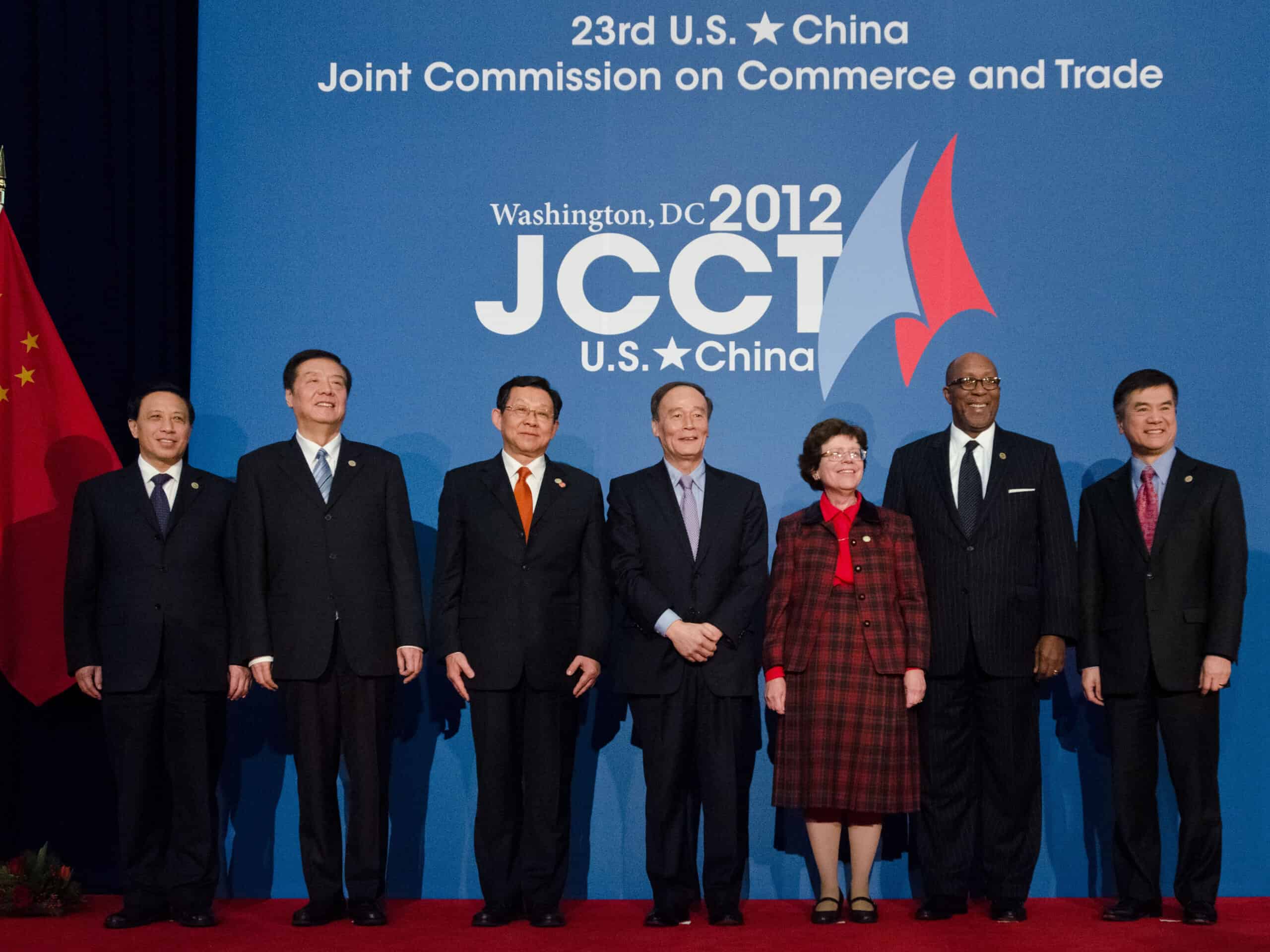

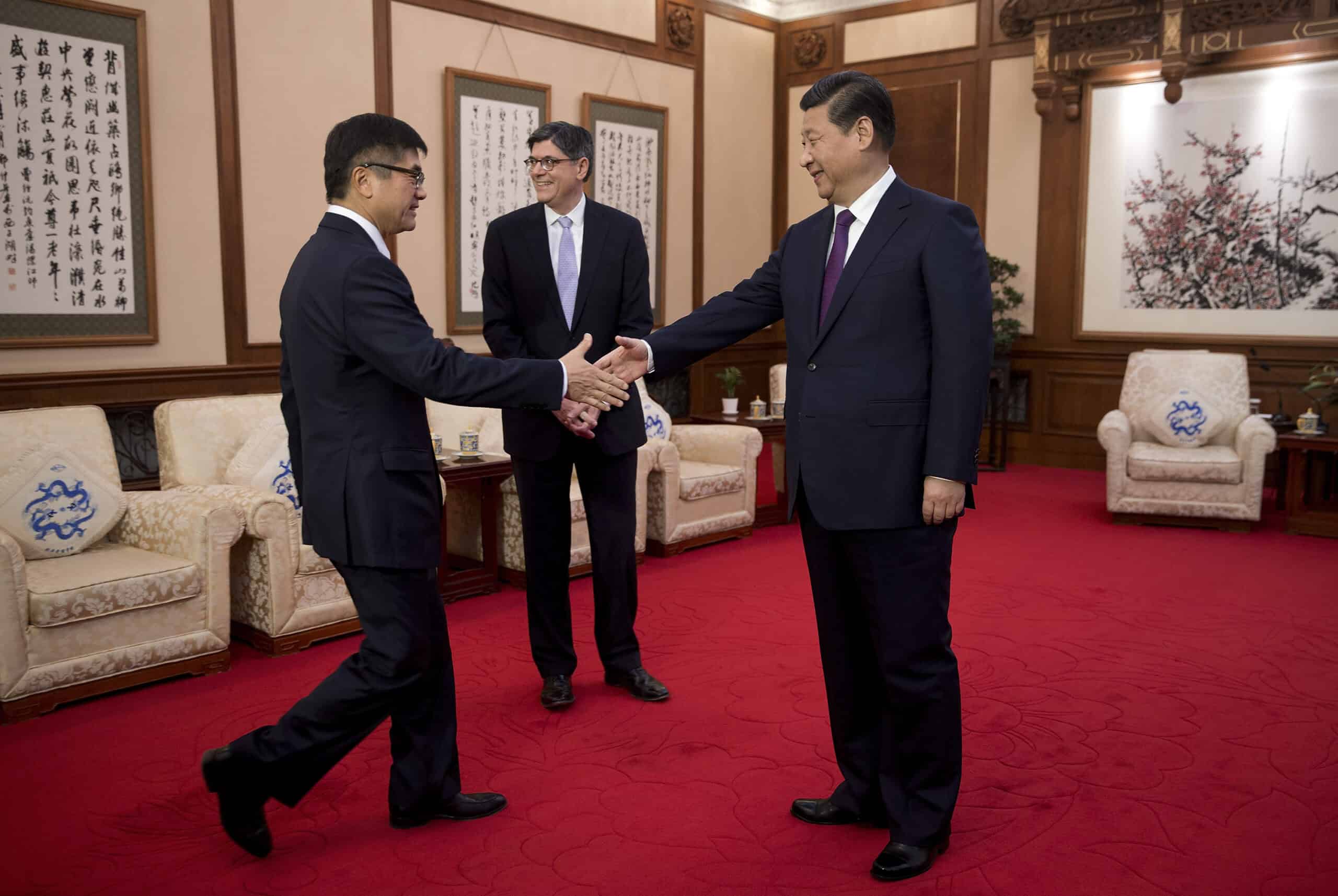

Gary Locke, then Ambassador to China, announces a new trade and investment initiative between the U.S. and China to increase bilateral ties. Beijing, China, September 20, 2011. Credit: U.S. Department of State

The pivot was basically a statement that America had been so preoccupied with the Middle East that we had somewhat disengaged or withdrawn our attention from the Asia-Pacific region. The pivot was a recognition that we needed to pay greater attention to the Asia-Pacific. Our allies in the region wanted us to have closer relations with them and to be more attentive to their issues.

The message from D.C. and from the embassy was that the pivot was not meant to constrain or limit China. Rather the U.S. is merely coming back to a region that America has long had an interest in, going back over 100 years. Our attention had been diverted during the Gulf wars from the region, but we wanted to be back.

Now, of course, with the current turmoil in Europe and the Middle East, we’re back in some ways to being focused on what’s happening in those regions again.

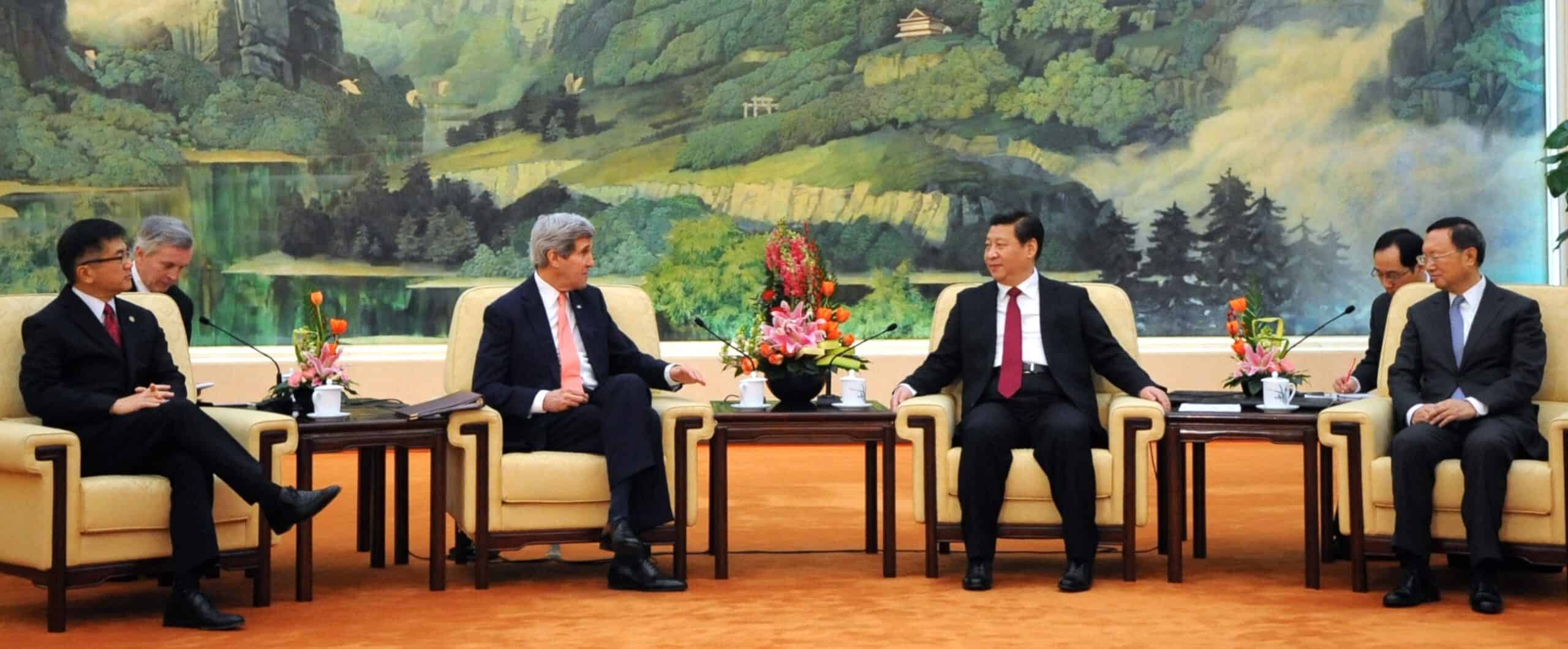

For this series, I did an interview with Obama Defense Secretary Ash Carter, which turned out to be the last interview he did before unfortunately he died. He made the case that the DOD shifted resources and so on. But he blamed the State Department — not Hillary Clinton [for not pivoting]. Clearly, he was blaming John Kerry although he didn’t mention Kerry’s name. Do you think that was accurate?

I’m not sure what he was referring to so I guess I wouldn’t be able to comment on that.

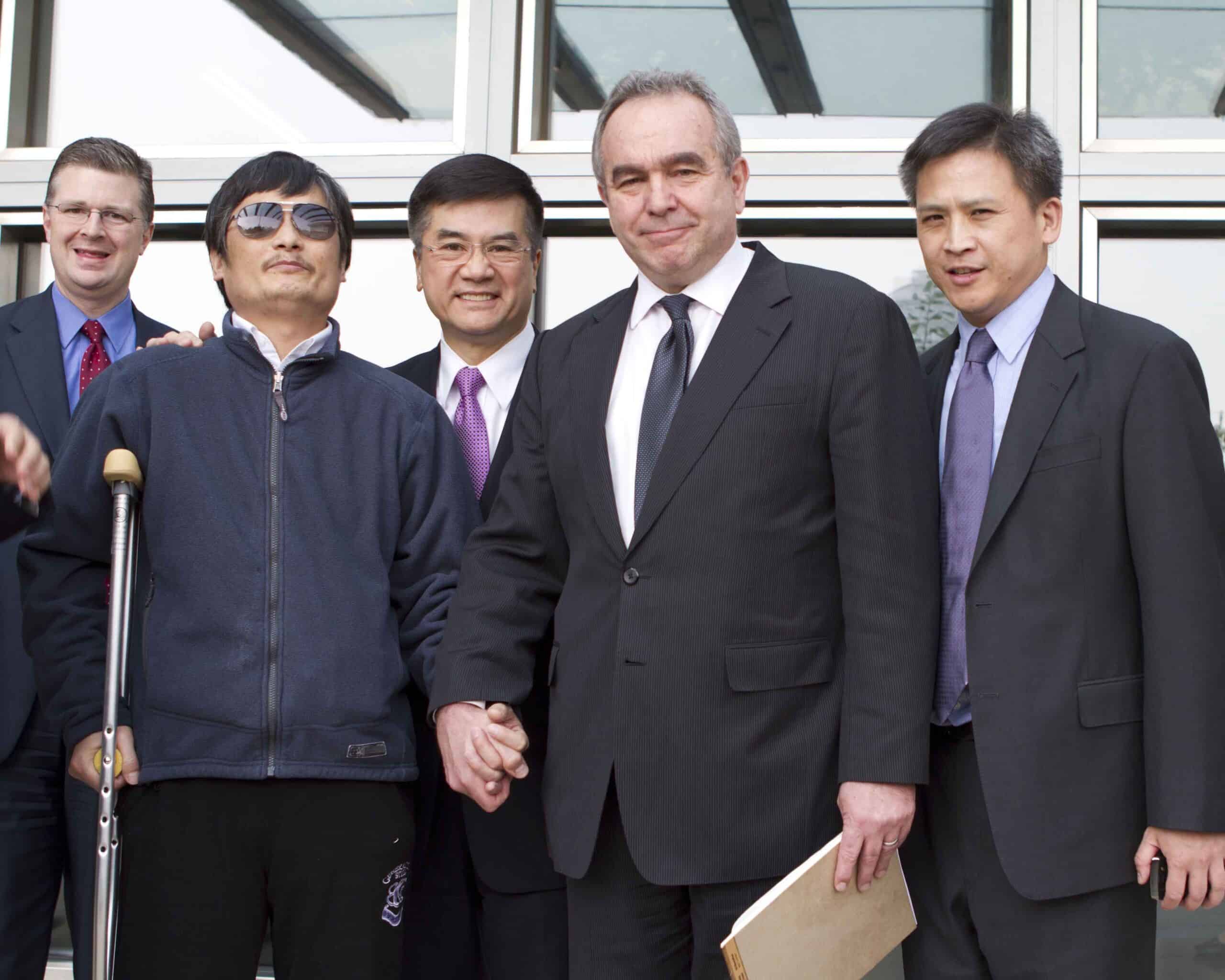

One of the events that got a lot of publicity when you were ambassador was when the blind dissident Chen Guangcheng sought refuge in the U.S. embassy, at a time when Hillary Clinton was visiting China. Later, Chen moved to the United States and made a speech at the 2020 Republican convention.

First of all, I’m very proud that the U.S government, the embassy, the State department team, the Obama administration, and Hillary Clinton were able to get Chen Guangcheng freed from the oppression of China. He never wanted to come to the United States. All he wanted was to be able to live in a different province, free from the persecution and the harassment of the local government officials.

We were negotiating on his behalf to enable him and his family to live somewhere else, while the Chinese government was demanding his immediate release from the embassy. When negotiations broke down at one point, we were prepared to have him live in the embassy for the foreseeable future.

We knew that that would threaten the upcoming high-level talks between the U.S. government and China which were slated to begin within a few days. Hillary Clinton, the secretary of Defense, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, the Treasury secretary and many other cabinet secretaries were coming [for a meeting of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in May 2012]. We were prepared to sacrifice the Dialogue in order to uphold our values of protecting a person who was being persecuted in China and who had been given refuge in the embassy.

In the end, the Chinese agreed to let him and his family live in a different province, and we escorted him to a hospital to receive needed medical treatment. Within days, he changed his mind and he wanted to come to the United States. But at that point we had no leverage. He was outside the protection of the embassy and in a Chinese hospital.

That’s when Hillary Clinton rose to the occasion and quietly negotiated with the Chinese government. A few weeks later, the Chinese government said that Chen Guangcheng, like any other Chinese citizen, was free to apply for a visa to leave the country.

He went to NYU, which took him in at great risk because they were opening a branch campus in Shanghai. They were concerned that taking him in and giving him basically free room and board for the next year or so, would cause the Chinese government to retaliate and withdraw permission for NYU to have that branch campus.

Then Chen Guangcheng was invited by many conservative organizations to give speeches and receive awards. They basically used him to fundraise and made him the guest of honor to help attract more donors and attendees at events. That’s unfortunate.

What did you think when he was talking to the Republican Convention?

I think he had been captivated by other groups. I’ll just leave it at that.

What do you think about the role of an ambassador when there’s instant communications? China is the focus of so much attention in Washington.

The role of foreign service officers and ambassadors to any country has changed dramatically over the decades in the face of instant communication and the internet. Decades ago, ambassadors and embassies communicated with Washington D.C. using cables, and communication was very slow. The State department, the White House, and Washington D.C. depended on communications from embassies and ambassadors to know what was going on in the country and to make recommendations on U.S. policy.

All countries try to promote their own domestic industries. But in the end, we still need to trade with each other, because there are many things that Americans want and need that are not produced here.

In the era of the internet, when we wake up in the morning in China or any other country, and we see what has happened overnight, we want to report that to Washington D.C. But D.C. already knows because of the time zone differences and with the internet.

Then U.S. Ambassador to China, Gary Locke, speaks to the press outside his family’s residence in Beijing, August 14, 2011. Credit: AP Archive via YouTube

So, a lot more policy now is made directly in Washington D.C., but with input from the foreign service officers. When I was ambassador, I was really trying to reinforce in the minds of our foreign service officers and all the members of the embassy team that our job is no longer simply to report what is going on, because D.C. knows what’s going on. But based on our contacts with people in China — whether scholars, businesspeople, academics, mid-level government officials — we need to be making recommendations or going a step further to talk about the implications of what is going on and what it means to American interests. We need to provide more insight as opposed to just reporting what’s going on.

It was hard to get the embassy personnel to embrace that type of expanded role because they’re so used to simply reporting, reporting, reporting, and leaving it to the ambassador to make those types of recommendations.

With the Obama administration, in his first term, Obama did almost nothing on trade issues. The second term, he did quite a bit with the Trans-Pacific Partnership and other things. Do you think Biden would be the same if he wins the election? In a second term, a bigger focus on foreign trade, particularly regarding China?

[The Trans-Pacific Partnership was the Obama administration’s flagship trade proposal to create a free trade pact among 11 Asia-Pacific nations. President Trump pulled the U.S. out of negotiations on his first working day in office. The TPP nations and others eventually signed what’s called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.]

I don’t really think it’ll be different. The restrictions on exports of advanced semiconductors and equipment necessary for the manufacturing of advanced chips will continue. Restrictions on trade under the Biden administration have been very targeted and very strategic, as they should be. I’m not in favor of carte blanche restrictions and tariffs.

The Trump tariffs across-the-board on Chinese goods have hurt the American consumer and have not really achieved the objectives that American companies and American policyholders have wanted. Our tariffs on Chinese goods have raised the price of goods for the American consumer. They also made made-in-America products more expensive when China retaliated, so we were not able to sell as much into China. And the tariffs increased the cost of American products using Chinese components, making American products more expensive compared to products coming from other countries.

While other countries have similar concerns as America has over China’s economic and trade policies, unfair subsidies, etcetera, etcetera, they’re sitting back and saying, ‘Wow, we hope America wins this trade war, but meantime we’re benefitting because our exports to China are not subject to retaliatory tariffs.’

The cost of those Chinese components that are incorporated into Western and other products are forcing prices to go up. So, American products now are at a competitive disadvantage compared to the products made by companies in other countries. They’re sitting back and saying, ‘Wow we hope America wins this trade war, but in the meantime we’re benefiting.’

Do you think Biden should repeal the Trump tariffs?

I don’t think he will unless China makes substantial policy changes to address the concerns that American businesses and policymakers have long had about China’s failure to fulfill many of their commitments that they made when they joined the WTO. China will have to make more measurable steps in addressing these concerns. In the meantime, the Biden administration will focus on targeted strategic restrictions on U.S. exports to China.

What if Trump is elected? How would you expect things to change?

| MISCELLANEA | |

|---|---|

| BOOK REC | The Boys in the Boat |

| FAVORITE FILMS | No real favorites, but among more recent films, The Martian. For holiday films, It’s a Wonderful Life |

| FAVORITE MUSIC | Tony Bennett, Beatles |

| MOST ADMIRED | John F. Kennedy |

He’ll continue those tariffs for sure. I think he’ll approach China with very much of a sledgehammer approach — an across-the-board approach as opposed to being very strategic and targeted.

I think there’s a natural decoupling going on. As we saw from COVID, we should not be so reliant on things coming from any particular country. All countries need to diversify their supply chain, whether because of a possible natural disaster that shuts whole sectors of an economy in, let’s say China or any part of the world, or because of political issues.

And China is doing exactly the same thing. They don’t want to be so reliant on advanced chips from the United States — and even everyday chips — or cell phones.

So, you see the world bifurcating?

All countries try to promote their own domestic industries. But in the end, we still need to trade with each other, because there are many things that Americans want and need that are not produced here. And there are so many things that we make that are so highly valued and in great demand and have great cache around the world.

Bob Davis, a former correspondent at The Wall Street Journal, covered U.S.-China relations beginning in the 1990s. He co-authored “Superpower Showdown,” with Lingling Wei, which chronicles the two nations’ economic and trade rivalry. He can be reached via bobdavisreports.com.