Large language models produced by Chinese AI firms have received a flurry of unexpected endorsements lately.

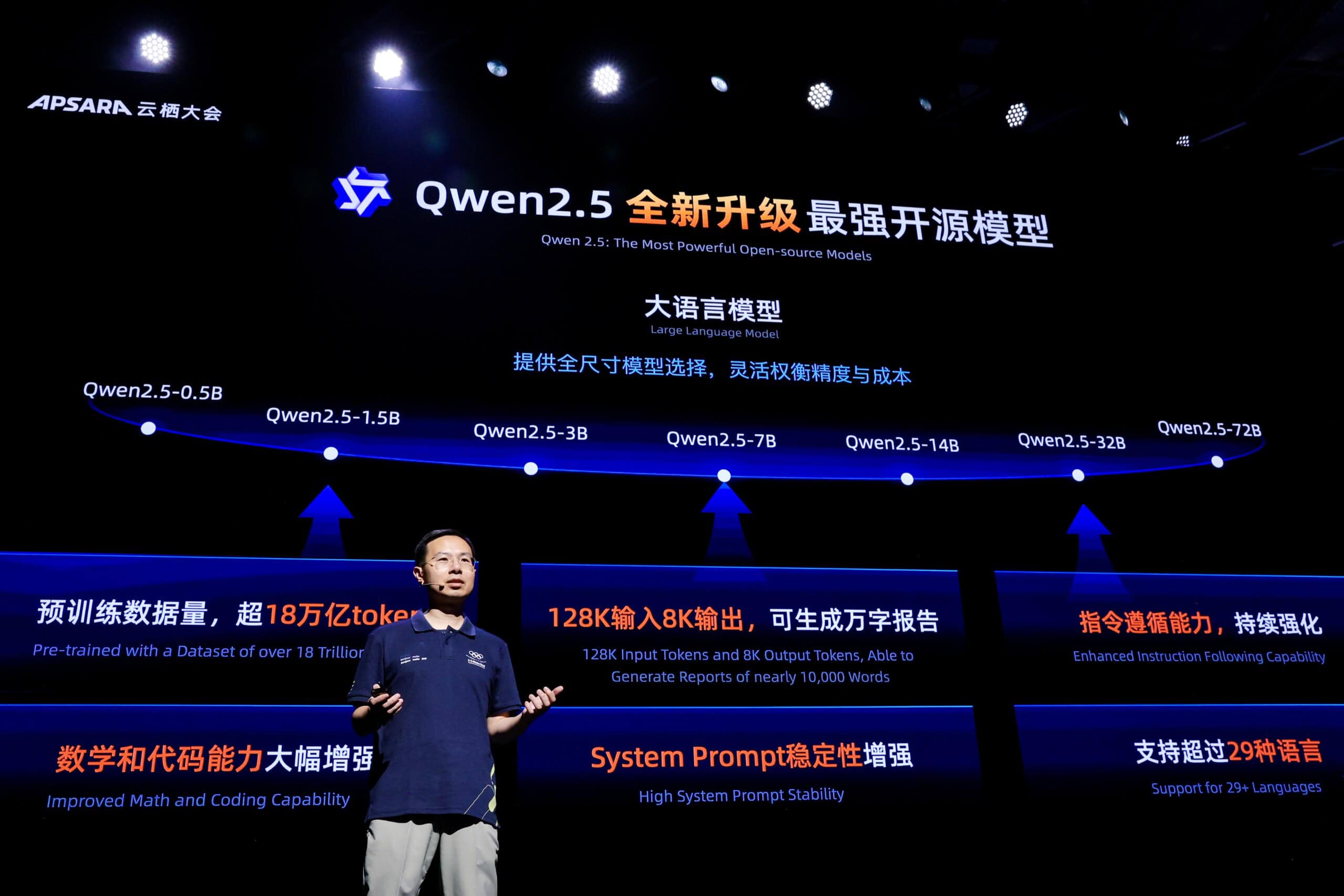

Brian Chesky, chief executive of Airbnb, caused a stir last month when he revealed that the company favours Alibaba’s Qwen over ChatGPT for its customer service chatbot, because it is “fast and cheap.”

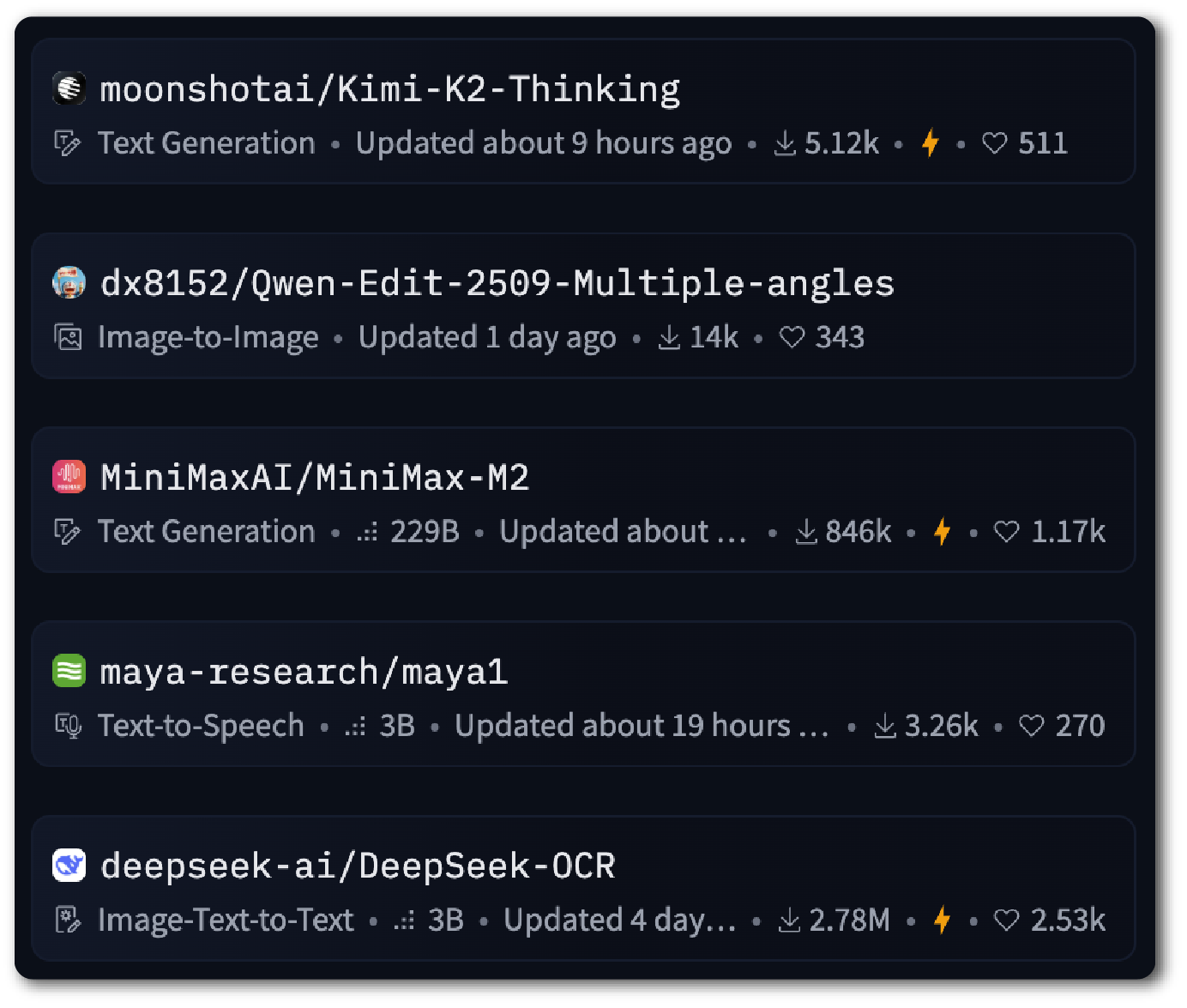

Before that, Chamath Palihapitiya, a prominent venture capitalist and former Facebook executive, said he has moved his company’s workflows from Amazon’s Bedrock to Beijing-based startup Moonshot’s Kimi K-2 model because it was “way more performant [sic].”

The same month, Thinking Machines Lab, a $12 billion startup led by Mira Murati, former chief technology officer of OpenAI, released a tool that helps users customize existing open source models — including eight from Qwen.

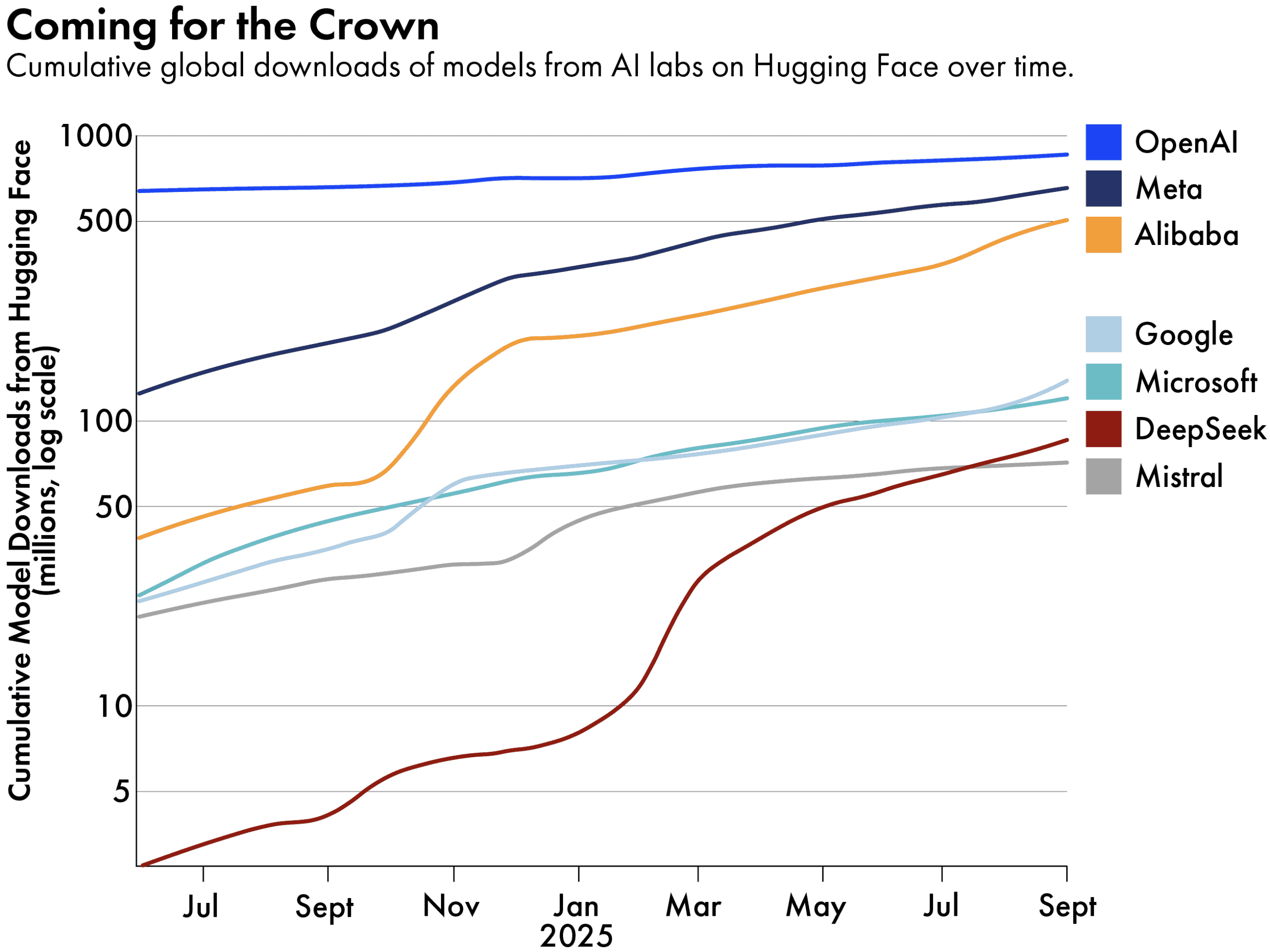

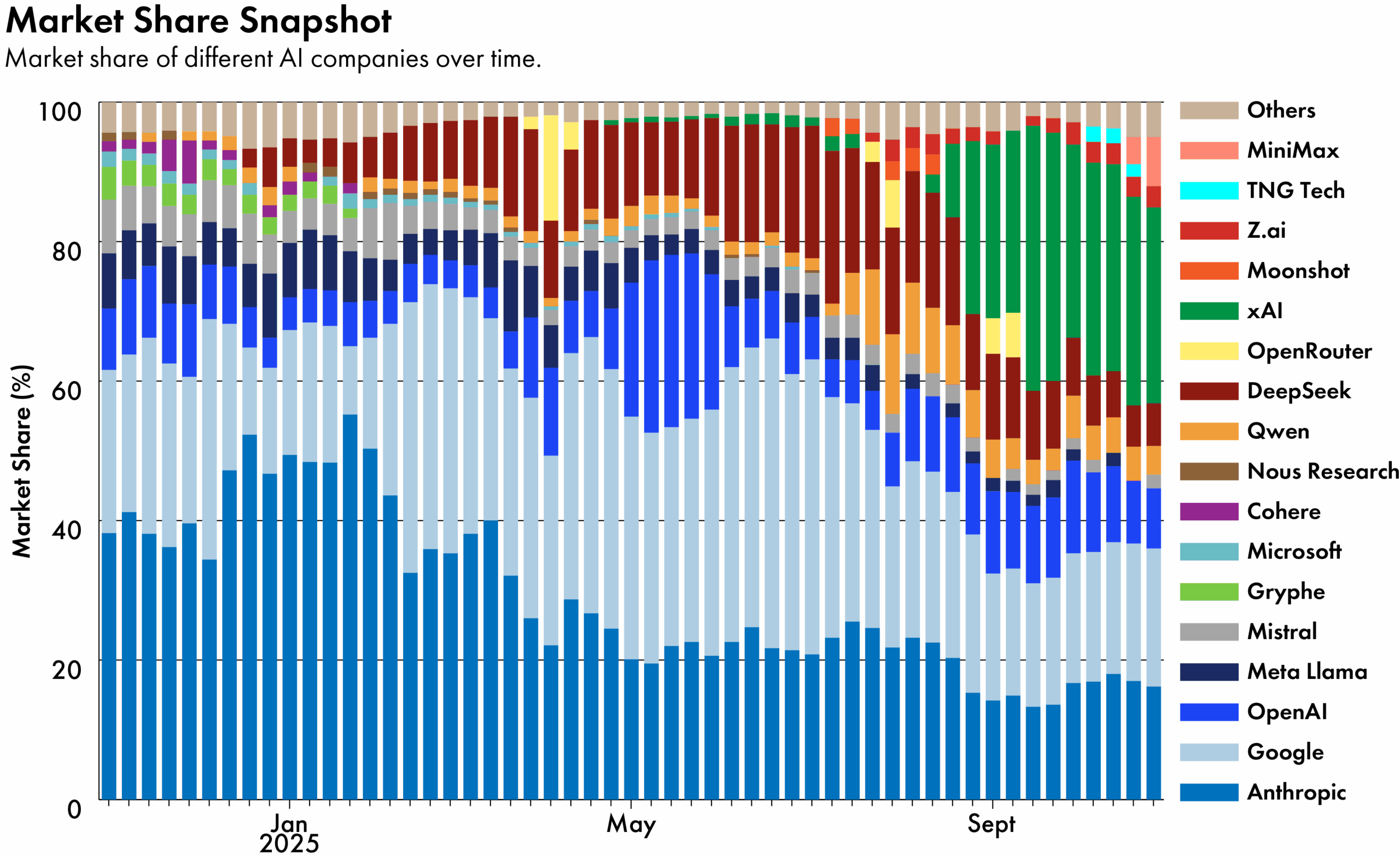

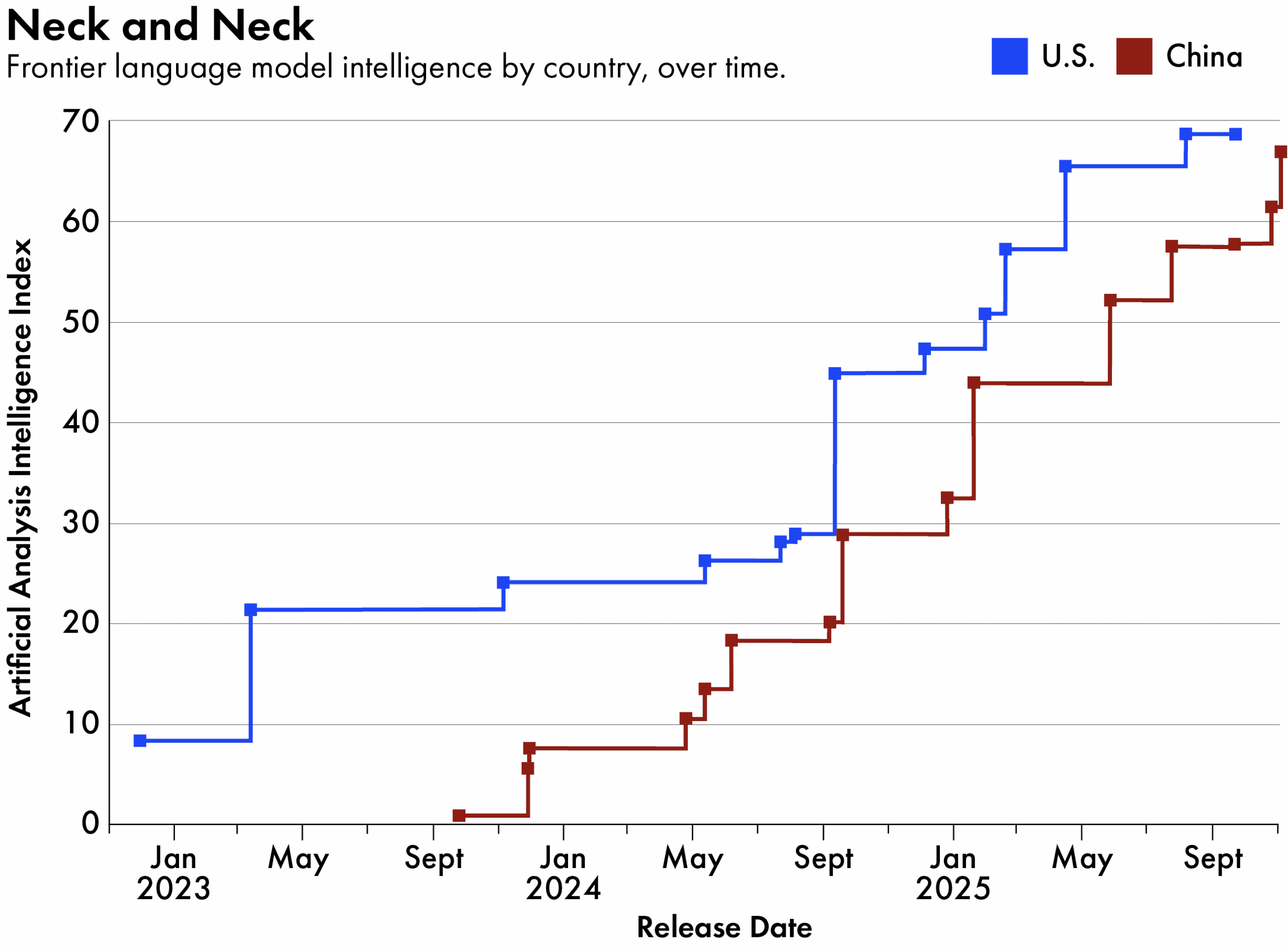

To many within the AI industry, these endorsements have come as little surprise. Chinese players have churned out increasingly competitive LLM offerings since the launch of DeepSeek first shook up the AI industry earlier this year.

To an average startup, what really matters is the speed and quality of the results, and if you’re doing things on scale, how cheap that is. Chinese models that are coming out in the market have consistently performed really well in terms of balancing those three factors.

Aman Sharma, co-founder of Lamatic, a South Florida firm that helps businesses build AI solutions

“These public examples are just the tip of the iceberg,” says Nathan Lambert, a machine learning researcher and author of the newsletter Interconnects. “I’ve personally heard of many other high profile cases, where the most valued and hyped American AI startups are starting to train models on the likes of Qwen, Kimi, GLM, or DeepSeek.” GLM is a model developed by Beijing-based startup Zhipu, which has recently rebranded as Z.ai.

Besides closing on U.S. rivals on various quality benchmarks, Chinese models are also winning over customers as geopolitical and cybersecurity concerns take a backseat to factors like cost, efficiency and ease of use. The shift in part represents a win for open-source technology, which many Chinese AI firms prefer as a way to speed up innovation.

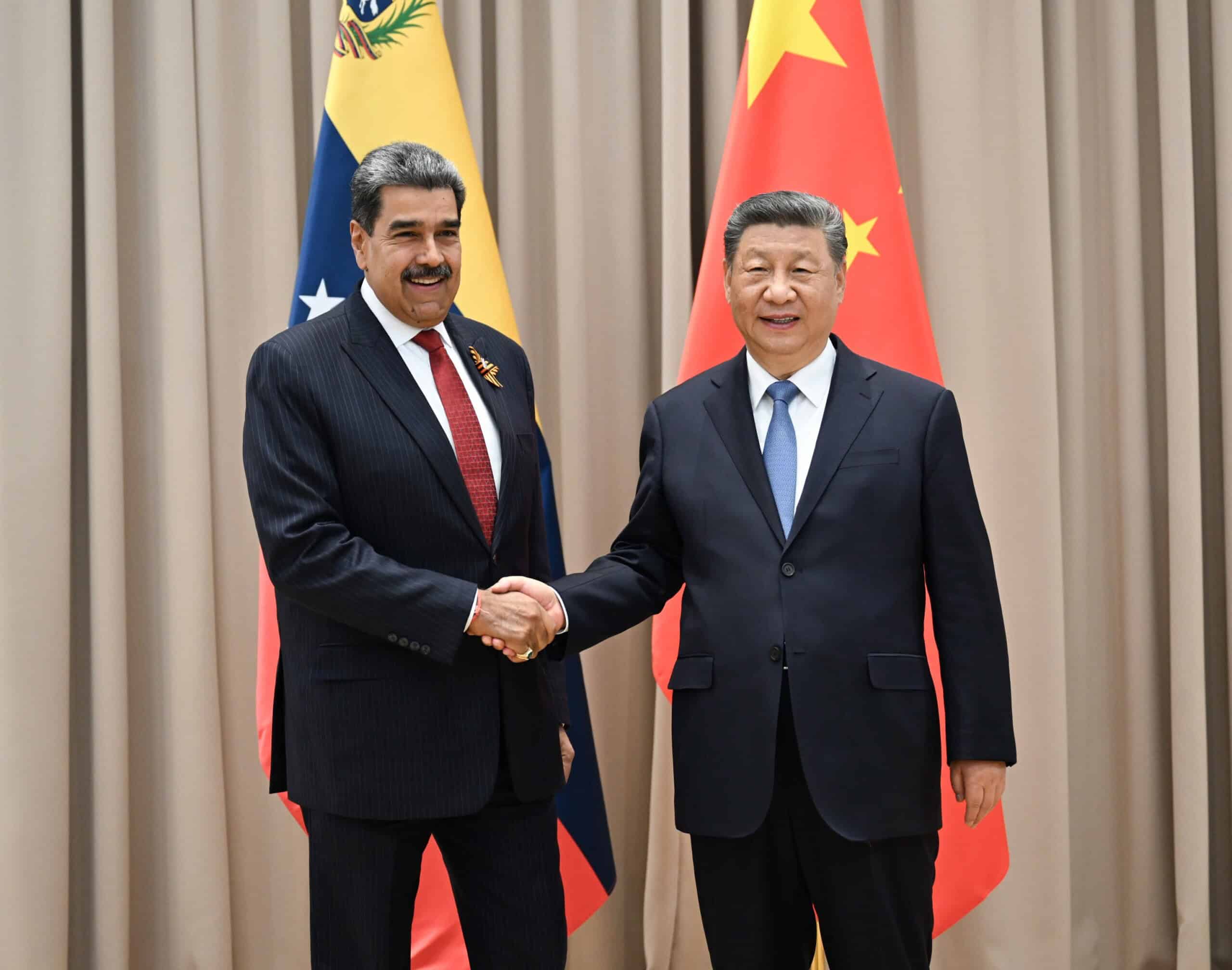

But some see the increased interest in Chinese models as a shot across the boughs of the U.S. AI industry — as well as a potential source of concern in Washington.

The U.S. government added Zhipu to a trade blacklist in January, citing its ties to the Chinese military, which the company has denied. A recent report by the Center for AI Standards and Innovation — part of the Commerce Department — warned both about potential security risks associated with foreign AI systems and that the growing use of Chinese models is “cutting into U.S. developers’ historic global lead.”

“If U.S. model developers are losing potential big tech company clients like Airbnb to Chinese competitors, it is a warning sign that their approach is not working very well,” says Sam Bresnick, a research fellow at the Georgetown University Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET). Bresnick adds that momentum is building in the U.S. to limit the use of Chinese LLMs within the government, which could extend to businesses at some point.

In the meantime, the likes of DeepSeek and Qwen have been trending on OpenRouter, a popular U.S. platform that directs developers to different AI models. They were both among the top ten most popular models on the platform last week, along with those from Z.ai and MiniMax, a Shanghai-based AI unicorn. This time last year, the chart was dominated by U.S. models.

The biggest factor where this matters is for government and high-stakes enterprise applications where security is paramount. There are natural concerns over what data the model was pre-trained and post-trained on and whether it exhibits behaviors the company wouldn’t want.

Nathan Benaich, founder of venture capital firm Air Street Capital

One reason for Chinese models’ soaring adoption is that many of them are what is technically known as ‘open weight’. U.S. companies tend to closely guard their models’ training data, code and architecture and restrict how they are used and distributed. But Chinese models usually come with more permissive licenses, allowing users to modify the parameters — also known as weights — that define a model’s internal structure and affect how it makes decisions.

“If you’re a startup, you can basically pull those weights off the internet and use your proprietary data to fine-tune them,” says Bresnick, describing a process whereby companies can train an existing model for specific tasks, such as coding or answering customer inquiries.

Strapped for cash, many startups are doing just that. Take Univa, a South Korean company that develops AI solutions to process documents for government departments: in September, it said Qwen’s open source software had helped it cut costs by 30 percent.

Alibaba itself now reckons there are over 170,000 models based on Qwen. The Chinese company leads globally in new derivative models uploaded to the U.S. developer forum Hugging Face every month, having overtaken Meta’s Llama since the start of this year.

The actual number of companies using Chinese models may be even higher.

Last week, Cursor, a San Francisco-based startup, impressed users with a new AI tool that can write code much faster than its peers. Its tendency to switch to Chinese characters and other technical features, however, have prompted widespread industry speculation that its base model is from China. Similar conjecture surrounds SWE-1.5, a coding agent released last week by another Silicon Valley startup, Cognition. Some users have linked it to Zhipu’s GLM-4.5, a model built for programming.

A demo of Cursor’s ‘frontier coding model’. Credit: Cursor

Zhipu declined to comment on the speculation. But Li Zixuan, Zhipu’s head of global operations, told The Wire China the company is “tracking a growing number of derivative and fine-tuned models across research [labs] and startups.”

Both Cursor and Cognition did not respond to requests for comment.

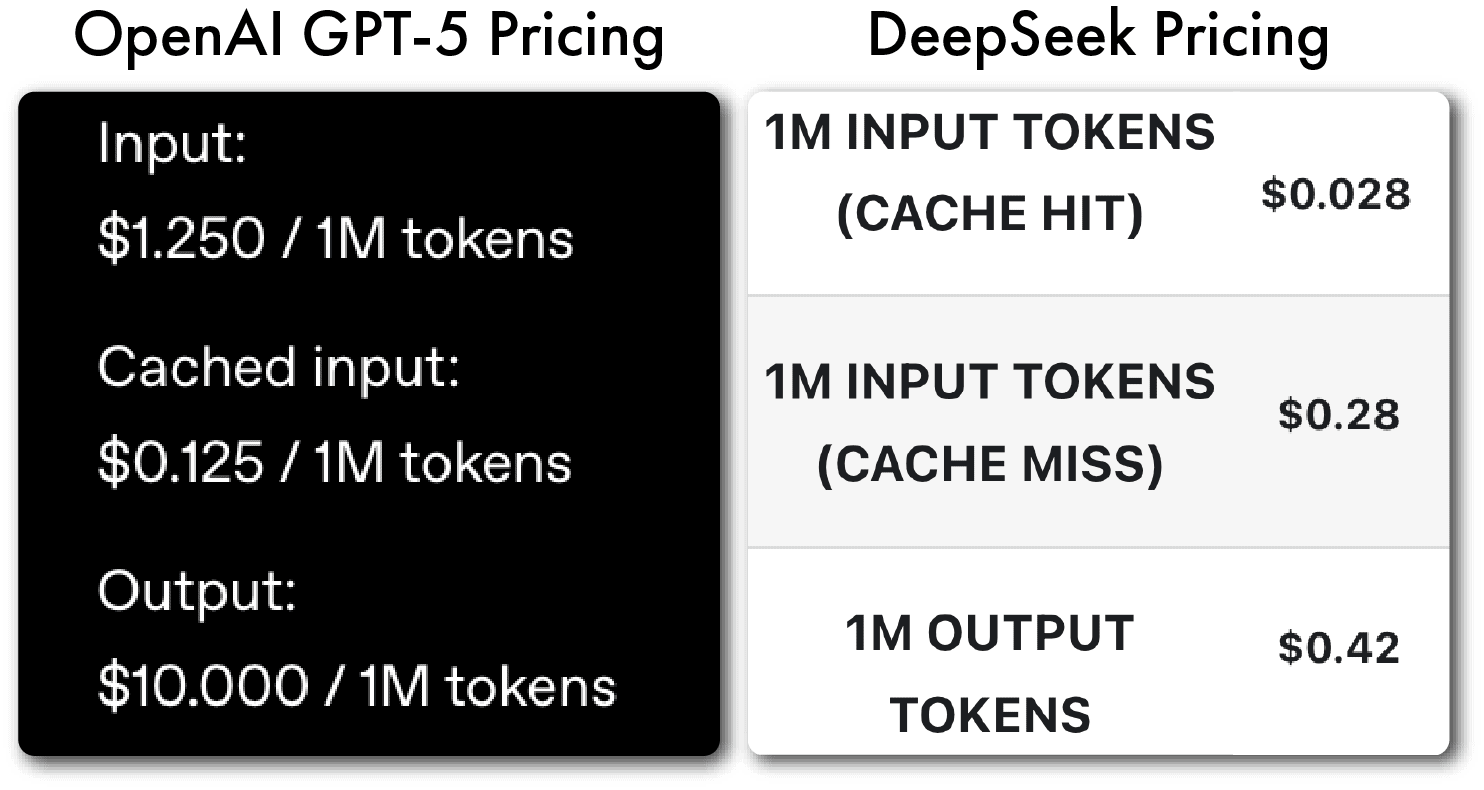

Another factor working in Chinese AI’s favor is pricing. For users, Chinese LLMs typically cost around one-fifth of their foreign counterparts, according to a new report by SuperCLUE, a Chinese group that ranks LLM capabilities. MiniMax, for instance, advertises its latest model M2 as a cheap alternative to Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4.5. They score comparably on several benchmarks, but M2 costs 8 percent of the latter’s price, as the company highlights in its social media posts.

“There is enormous global demand for AI right now, and we see major opportunities for companies that can truly innovate,” a MiniMax spokesperson told The Wire China in an email.

The long term dominance of American AI depends heavily on an unpredictable trajectory of the technology, if we continue to cede the lead in open source to China.

Nathan Lambert, a machine learning researcher and author of the newsletter Interconnects

Some analysts say Chinese companies are deliberately aiming to undercut their American and other international rivals. But the low prices also reflect local market realities. “Chinese models are trying to globalize, but they still primarily service Chinese customers, and no one’s going to pay OpenAI prices,” says Rui Ma, founder of the research firm Tech Buzz China.

“To an average startup, what really matters is the speed and quality of the results, and if you’re doing things on scale, how cheap that is,” says Aman Sharma, co-founder of Lamatic, a South Florida firm that helps businesses build AI solutions. “Chinese models that are coming out in the market have consistently performed really well in terms of balancing those three factors.”

In certain sectors, the use of Chinese models — including products built on top of them — is still a definite no-no. “The biggest factor where this matters is for government and high-stakes enterprise applications where security is paramount,” says Nathan Benaich, founder of Air Street Capital, a venture capital firm in London that specializes in AI companies.

Some researchers have identified political biases and censorship in Chinese models as well. “There are natural concerns over what data the model was pre-trained and post-trained on and whether it exhibits behaviors the company wouldn’t want,” Benaich adds.

Nevertheless, there is considerable interest in Chinese offerings. A July survey by Artificial Analysis, a San Francisco-based company that develops AI benchmarks, found that up to 82 percent of users are open to using Chinese LLMs, provided that they are hosted on infrastructure based outside of the country.

Chinese AI companies are still nowhere near the likes of OpenAI when it comes to revenue or market valuation. But some observers say their growing traction indicates that AI labs and companies in the U.S. ought to rethink their strategy, especially their fixation with proprietary models.

“The long term dominance of American AI depends heavily on an unpredictable trajectory of the technology, if we continue to cede the lead in open source to China,” says Lambert, who has started a campaign to advocate for more resources towards homegrown open source models.

Rachel Cheung is a staff writer for The Wire China based in Hong Kong. She previously worked at VICE World News and South China Morning Post, where she won a SOPA Award for Excellence in Arts and Culture Reporting. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Columbia Journalism Review and The Atlantic, among other outlets.