President Joe Biden’s staff spent the first two years of his presidency preparing one of the most consequential foreign policy decisions of the decade: an arsenal of export controls aimed at hobbling China’s ascent in chipmaking and artificial intelligence.

At stake, they believed, was America’s lead in AI, which officials viewed as critical for national security. But the costs were also high. They would need to force U.S. allies to comply with far reaching trade restrictions and potentially hurt the sales of some of America’s most valuable companies, including the chipmaking giant Nvidia.

By early 2022, Biden had signed off on the controls.

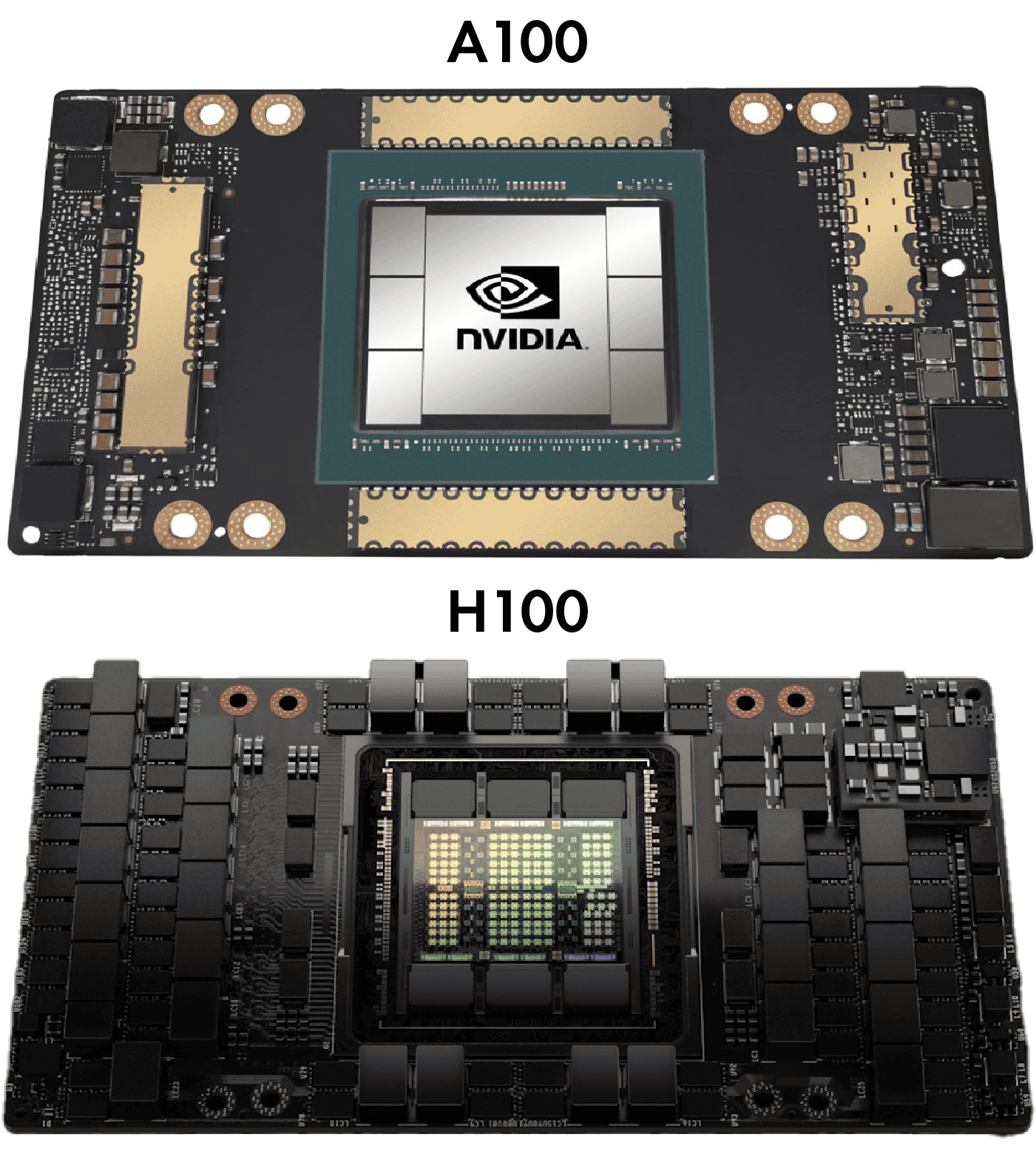

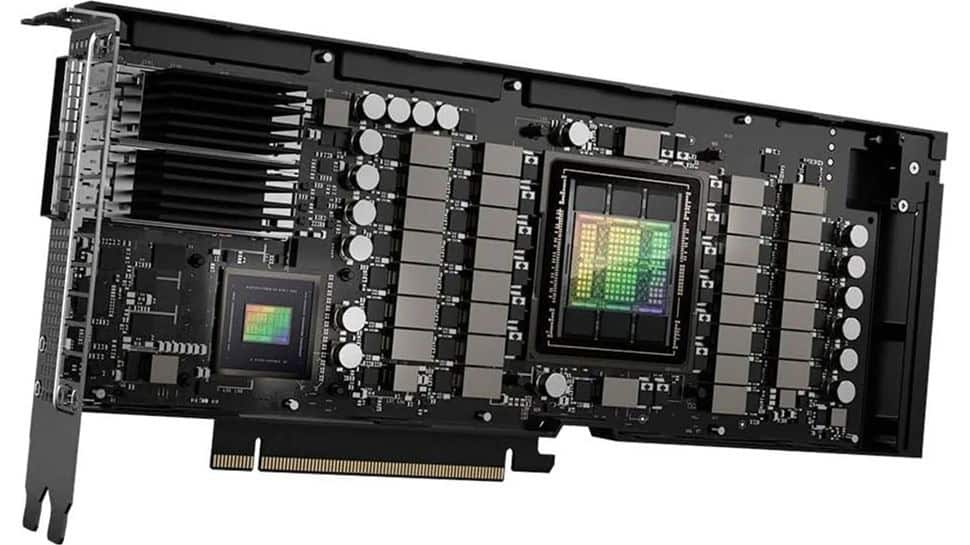

At the time, Nvidia was preparing to begin full production of its most powerful chip, the H100. Negotiations with Japan and the Netherlands, whom the U.S. hoped would join the controls, were moving slowly. Officials wanted to strike before Chinese companies could acquire H100s, and while China’s ability to make its own semiconductors was still constrained.

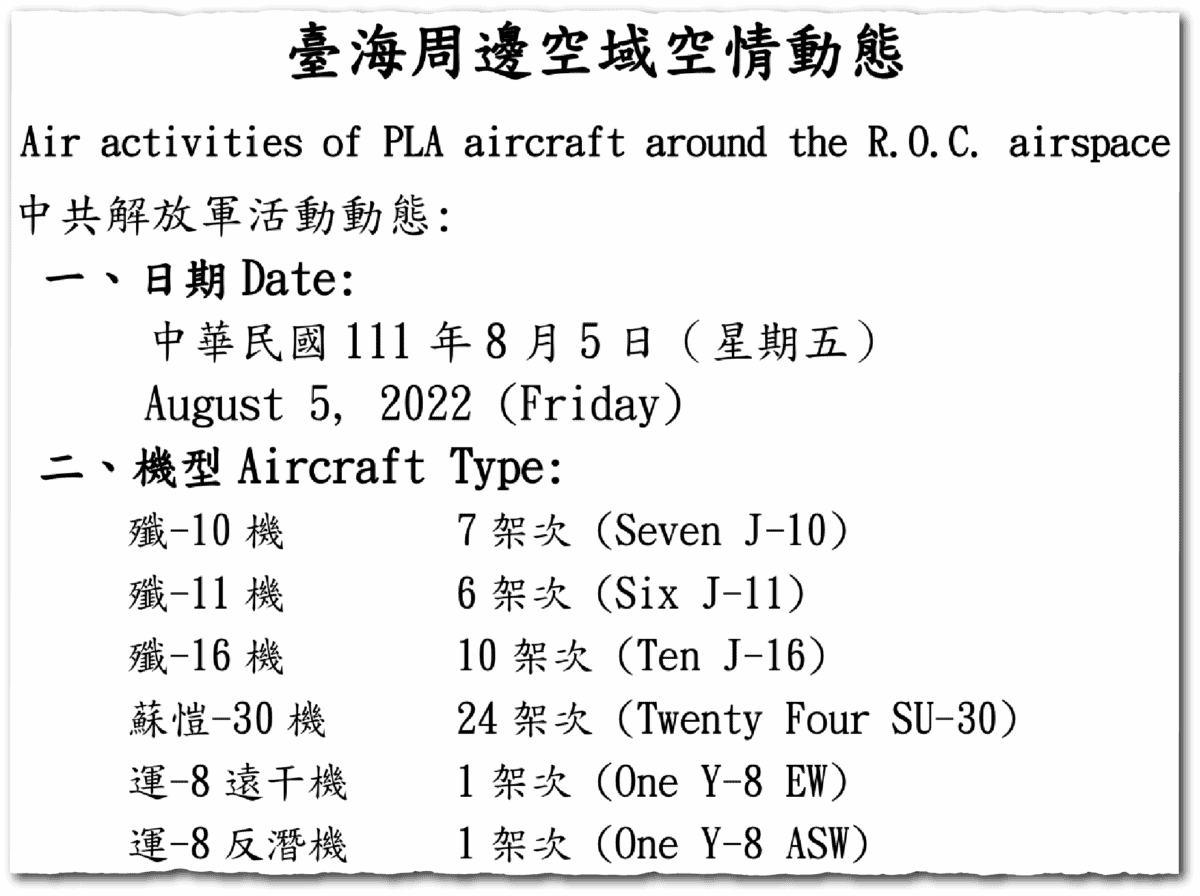

Then, on August 2, 2022, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan. China responded with fury. Almost two hundred Chinese planes broached Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone the week after Pelosi departed; more than a dozen warships sailed in and around the Taiwan Strait; and the PLA fired missiles into splash zones surrounding the island.

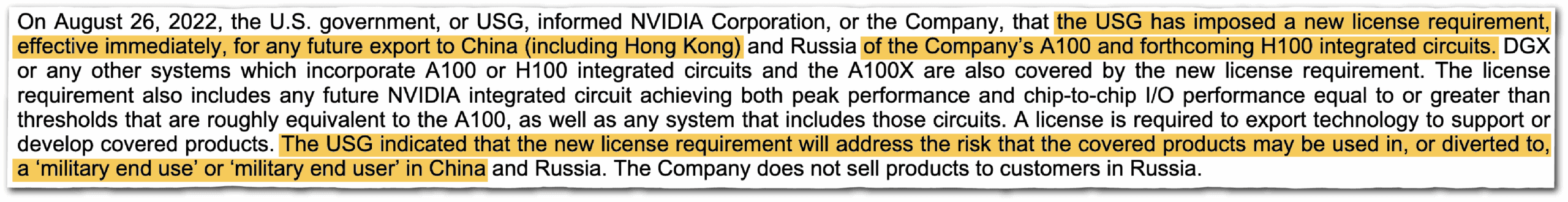

The extraordinary reaction by Beijing created an “enabling environment” for the controls, a former official recalls. That month, Biden officials privately informed Nvidia that it had imposed a new licensing requirement on two of the company’s flagship AI chips, the A100 and H100. “Steps that were well under way became all the more urgent,” the official says. While they add that the export controls were not a direct response to China’s aggression, the nature of the exercises “clarified” the need to act quickly.

‘AS LARGE OF A LEAD AS POSSIBLE’

Weeks later, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan signaled that the Nvidia filing was part of something bigger. Speaking at a Washington think tank on September 16, he said that staying “a couple of generations ahead” of China on technologies like semiconductors was no longer sufficient. “We must maintain as large of a lead as possible.”

When the policy dropped on October 7, 2022, it struck analysts like a lightning bolt. A “genuine landmark in U.S.-China relations,” one observer called it. “An act of war,” said another.

“We are at an inflection point,” added Secretary of State Antony Blinken, ten days after the policy was announced. “The post-Cold War world has come to an end, and there is an intense competition underway to shape what comes next. And at the heart of that competition is technology.”

The export controls turned the U.S.-China trade war that started under the first Trump administration into an all-out battle for technological supremacy. It triggered a cycle of tit-for-tat retaliation, as China restricted U.S. access to a growing swathe of critical minerals and rare earths. It also marked the beginning of a vociferous, years-long debate among U.S. government officials, foreign policy experts, industry lobbyists and the chief executive of the world’s most valuable company over whether Washington can prevent China’s technological rise.

For most of that time, the hawks had the upper hand. The controls have been cheered by both parties in Congress. Republican lawmakers not only welcomed the Biden administration’s move — they wanted more. Until January of this year, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), which oversees export control policy, dutifully complied, stacking increasingly onerous rules on top of rules, further choking off China’s access to chips and chipmaking equipment.

“Frontier AI will confer strategic, military, and intelligence advantages that America should never surrender to China or any other strategic competitor,” Sullivan told The Wire. “Strong controls on AI chips and chip manufacturing equipment, which are essential for our national security and AI leadership, should not be up for negotiation.”

During the second Trump administration, export controls have become bargaining chips in trade negotiations with China. And in a stunning concession last month, the administration reversed a ban it had imposed on sales to China of Nvidia’s H20 and Advanced Micro Devices’ MI308 AI chips in exchange for a gratuity-like 15 percent cut.

“I don’t think the U.S. understands that we have just handed China the key to unlock their biggest constraint in the AI race,” says Liza Tobin, managing director at Garnaut Global, who served as China Director on the National Security Council in the first Trump and Biden administrations. “We know that China has ambitions to become self-reliant, but they have not been able to get there yet in advanced AI semiconductors. So we’ve given them a bridge between their short term constraints and the long term goal.”

The administration has made some moves to tighten China’s access to chipmaking equipment, including a rule on August 29 that will require semiconductor giants Intel, Samsung and SK Hynix to obtain individual licenses to ship gear to their Chinese subsidiaries. The U.S. applied a similar restriction to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

We are first and foremost in a transactional environment right now. Export controls aren’t in vogue. The administration won’t do much on export controls before they’ve buttoned up the majority of what the president wants to do on trade.

a former official who worked in the first Trump and Biden administrations

To understand how U.S. policymakers conceived and developed one of their most audacious strategies to take on China — and the unexpected change of tack this year — The Wire spoke to more than two dozen current and former government officials across the Biden and two Trump administrations. Many spoke on condition of anonymity in order to discuss internal deliberations, or for fear of reprisals from the current administration.

Some officials argue that Trump’s shock deals with Nvidia and AMD were not a deliberate reversal of U.S. strategy, but rather reflect an internal vacuum that has left China tech policy at the whim of the president. Key bodies that previously drove export control policy, including the National Security Council, have been gutted, depriving the administration of much technical expertise.

As a former official put it: “Imagine trying to build a nonproliferation regime with no physicists.”

At Commerce, current and former officials say export controls have taken a backseat to trade negotiations. License approvals have ground to a halt, leaving tens of thousands of applications stuck in limbo, but also depriving Chinese companies of chips and tools. An exodus of specialist staff means that work on a long-term strategy to regulate AI chip exports has slowed too.

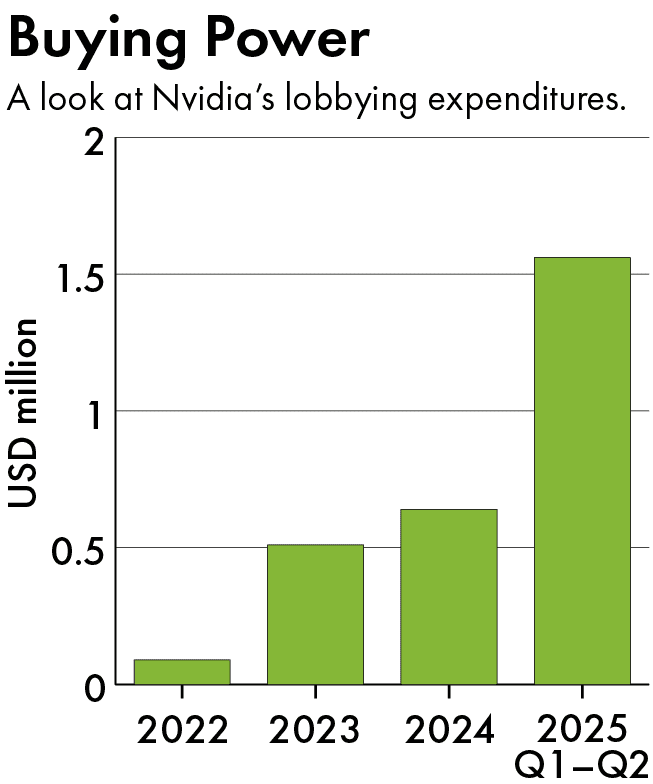

This has created a golden opportunity for companies like Nvidia, which wants to sell more chips to China. The $4 trillion company was caught off guard when the Biden administration introduced its sweeping semiconductor controls in 2022, and its lobbyists have struggled to curry favor in Washington. Into the fray has stepped Nvidia Chief Executive Jensen Huang, who has found a way to cut past the bureaucracy and strike deals directly with the president.

What is unclear is whether more concessions are to come. At a press conference on August 11, Trump was asked about Huang’s ambition to sell a downgraded version of his company’s powerful next-generation chip, the B300, to China. “I think he’s coming to see me again about that,” the president said.

President Trump responds to a question on Nvidia’s chips, August 11, 2025. Credit: The White House

“We are first and foremost in a transactional environment right now,” says a former official who worked in the first Trump and Biden administrations. “Export controls aren’t in vogue. The administration won’t do much on export controls before they’ve buttoned up the majority of what the president wants to do on trade.”

‘GO FOR THE JUGULAR’

The Biden administration wasn’t the first to see the rise of China’s semiconductor industry as a threat.

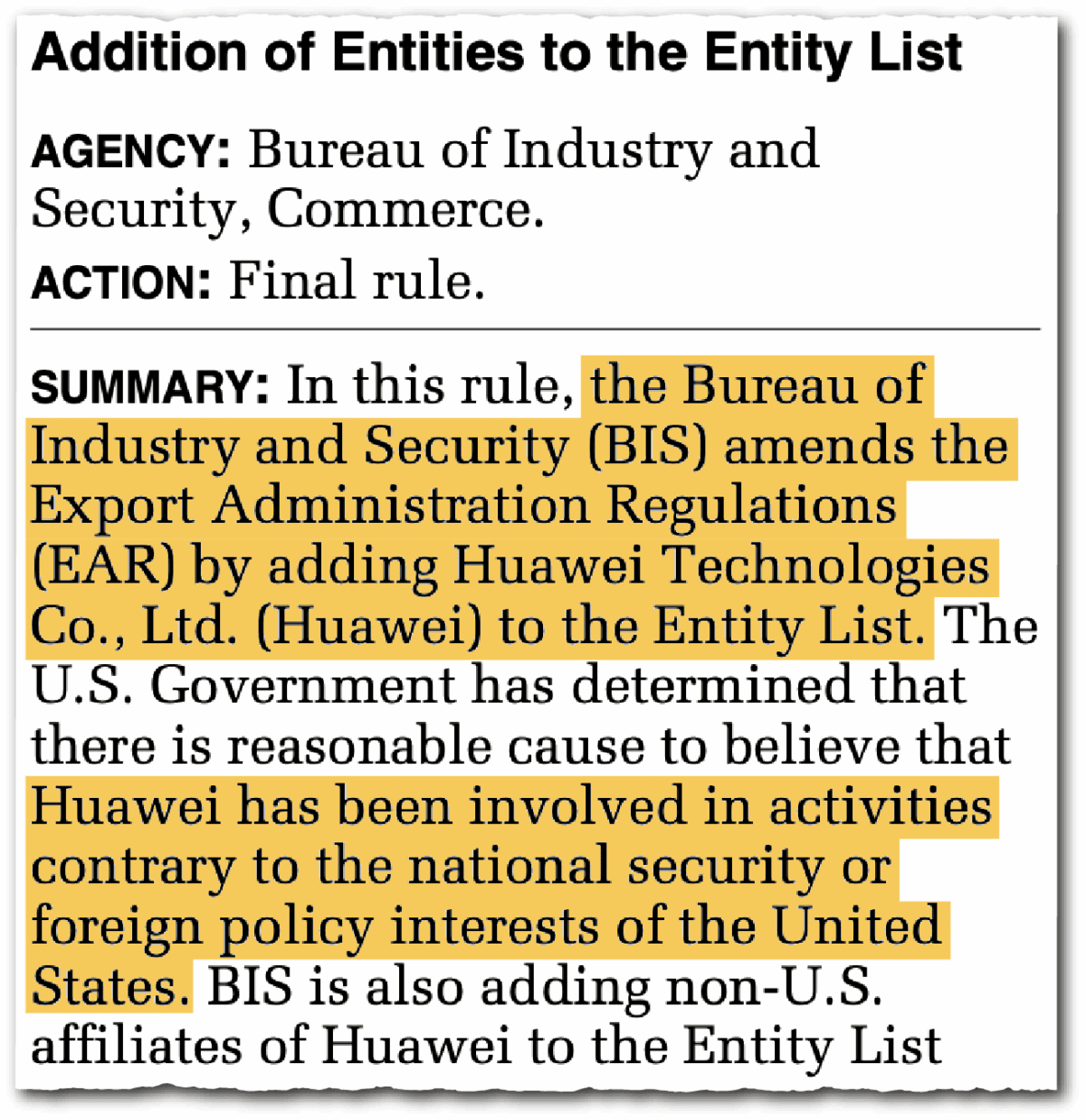

In 2019, Trump’s first administration added Huawei to the Entity List, blocking the Chinese tech giant from accessing American technology without a license. The effort was not effective.

“The first batch of Huawei export controls were a humbling experience for the Trump administration,” says Gregory Allen, a senior advisor with the Wadhwani AI Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “There was a massive gap between the amount of pain they thought and told everyone they were going to inflict, and what they actually inflicted. Companies basically said their goods weren’t U.S. exports because they didn’t depart from U.S. shores.”

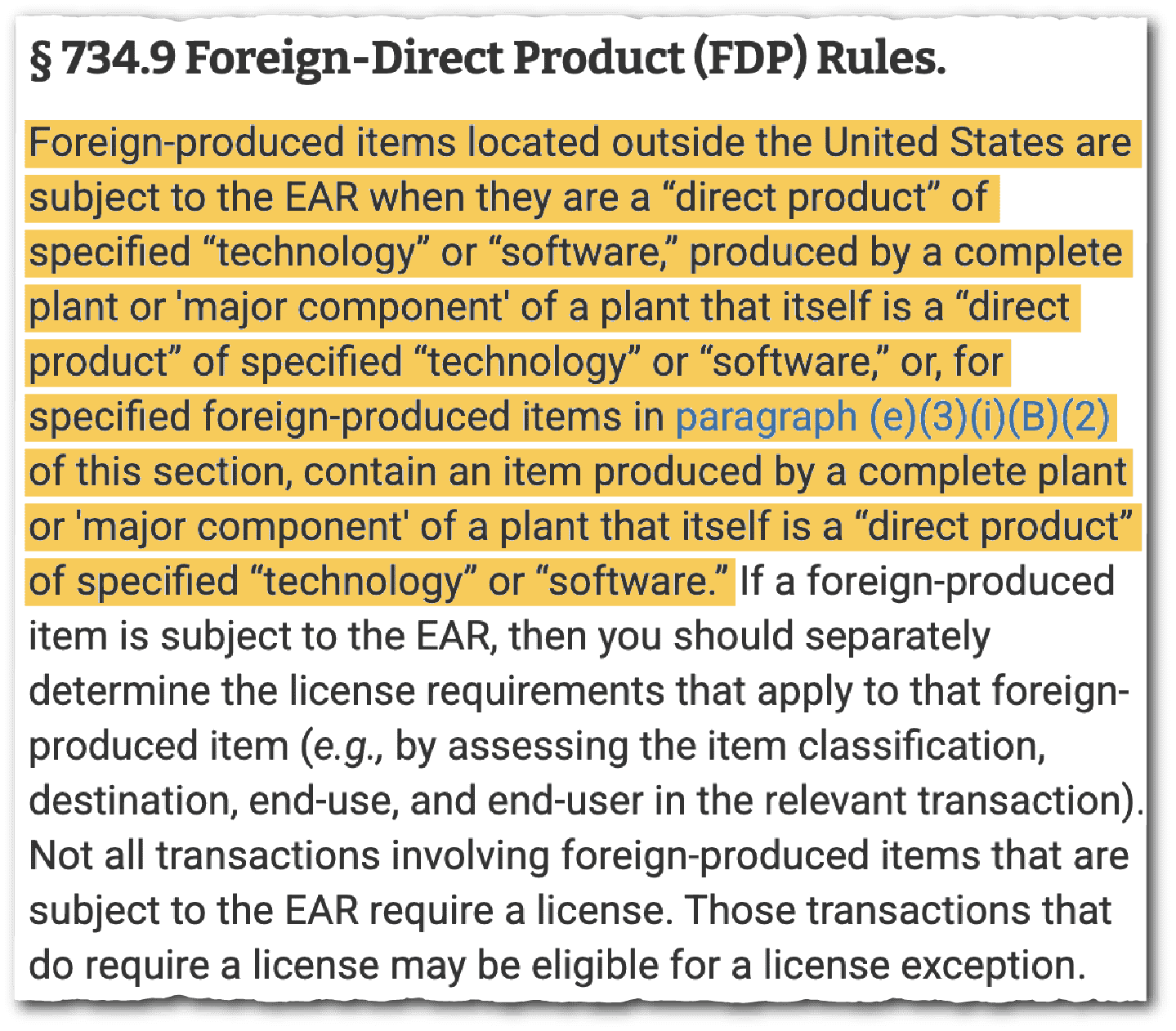

Undeterred, the administration doubled down, invoking an obscure provision known as the foreign direct product rule in 2020. The FDPR allowed Washington to vastly extend its jurisdiction to cover goods made anywhere, as long as their production involved American inputs or know-how. It allowed the Commerce Department to restrict, for example, TSMC from selling to Huawei, even though its chips were neither manufactured on, nor transited, U.S. territory.

Trump’s Commerce Department also sought to undercut China’s chipmaking capacity by adding Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) — China’s leading chipmaker — to a trade blacklist called the Entity List, and pressuring the Netherlands to restrict sales of national champion ASML’s most advanced chipmaking equipment to China.

Around the same time, a group of analysts outside of government were proposing new ways to ensure U.S. dominance of AI.

“We realized we had a chokepoint in the semiconductor supply chain, and the Trump administration demonstrated we had the regulatory tools to cut the Chinese off,” says Chris McGuire, who at the time was leading research at the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI), a congressionally-mandated body tasked with studying how AI development could bolster U.S. national security. In 2021 it recommended export controls on China as part of a 750 page report to Congress.

Separately, at the Washington-based Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), a think tank affiliated with Georgetown University and led at the time by Jason Matheny, scholars including Ben Buchanan, Tarun Chhabra, and Saif Khan co-authored reports calling for the U.S. and its allies to double down on controlling the flow of chips and chipmaking equipment to China.

“CSET and NSCAI were the two most influential [non-government] institutions thinking through potential policies and their desirability and likely implications,” says Allen.

By 2021 Buchanan, Chhabra, Khan, Matheny, McGuire and other CSET alumni had joined the Biden administration, fanning out across the National Security Council and Office of Science and Technology Policy. As early as the transition, they had been instructed to begin work on export controls for semiconductor manufacturing equipment. With backing from Sullivan, they quickly began translating their ideas into a plan that would limit its flow to China. A critical extension of the plan would also cover AI chips themselves, and use the FDPR to make sure companies in other countries couldn’t sell to China either.

The decision to impose FDPR on China helped inform U.S. policy when Russia amassed troops on its border with Ukraine at the end of 2021. According to two people familiar with the matter, at a Christmas party that year, Sullivan asked: “If we’re planning to do this to China, why wouldn’t we do this to Russia?” The U.S. announced sanctions on Russia using the FDPR immediately after Russia’s full-scale invasion the following February.

Using metaphors like “use a scalpel” and “be surgical,” President Biden urged his team to continue pursuing the China controls, but to keep them narrow and tailored, former officials recall. Sullivan referred to a “small yard, high fence” approach.

Tarun [Chhabra] knew exactly what he was doing the day he got in and had a clear sense of purpose and mission about using the tools we have. They used the existing statutory framework and stretched the rubber band as far as it could go.

a former Commerce official

On matters of economic and technological competition with China more broadly, the president was more assertive, according to four people with knowledge of his instructions. He told his team: “Go for the jugular.”

Several former officials say that Chhabra emerged as a key architect of the policy, corralling the necessary cooperation from multiple departments — Commerce, Defense, Energy, State — as well as the NSC.

“Tarun knew exactly what he was doing the day he got in and had a clear sense of purpose and mission about using the tools we have,” says a former Commerce official. “They used the existing statutory framework and stretched the rubber band as far as it could go.”

The Commerce Department’s first set of export controls restricted sales of high-performance chips and chip manufacturing equipment — especially those intended for AI — and set a presumption of denial for exports to China.

“One of the biggest surprises was just the fact that we’re not going to be selling AI chips [to China] at all,” says Doug O’Laughlin, president of consultancy SemiAnalysis. It was, he says, “a strangling.”

FRIENDS AND FOES

Almost as soon as the controls were announced, the White House began fielding a torrent of calls from alarmed allies and firms. Sullivan spoke directly with the leaders of many companies, according to two people familiar with the matter.

For months, the U.S. had been negotiating with the Netherlands and Japan, hoping that they would join in imposing China export controls on their own companies, such as ASML and Tokyo Electron. Dutch and Japanese officials were initially reluctant to do so.

The White House decided to push ahead anyway.

Then President Biden with then Japanese Prime Minister Kishida (left), January 13, 2023, and then Prime Minister of the Netherlands Rutte (right), January 17, 2023. Credit: Biden White House Archived via Flickr

“We were willing to go this alone as a down payment and show that we had skin in the game while we’re having the discussions with our allies,” Under Secretary of Commerce for Industry and Security Alan Estevez said the month the rule came out. “We had the rule ready and we decided to execute it.”

After the U.S. imposed controls, discussions with the Netherlands and Japan sped up. In January 2023, Sullivan separately hosted his Dutch and Japanese counterparts at Blair House, the plush home near the White House where foreign dignitaries stay on official business. He presented them with a gift of three arrows stitched together on white fabric — an allusion to a Japanese parable about strength in numbers. By the end of the month, the Netherlands and Japan had agreed to follow the U.S. lead.

The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry declined to comment.

White House officials also had to contend with protests from American companies whose sales to China were hit by the controls.

The three largest American chip equipment firms, Applied Materials, KLA, and Lam Research, argued that U.S. restrictions were stifling their ability to compete with foreign rivals. They hired the consulting firm run by Bruce Mehlman, a well-known Washington lobbyist whose brother once chaired the Republican National Committee, and inundated members of Congress and federal agencies with letters. (Mehlman and Lam Research did not respond to requests for comment. Applied Materials and KLA declined to comment.)

“The [semiconductor equipment makers] played a very smart game where they have been cooperative to a point where they convinced a lot of people in the government that we could do these smart, targeted regulations,” one person familiar with their discussions with the administration says. “It’s allowed them to continue to do a ton of business in China. That may actually have been a mistake.”

Nvidia’s lobbying efforts were less effective. The company adapted quickly to the initial export controls in 2022, which cut off sales of its flagship A100 and H100 chips to China, by developing modified chips for the Chinese market known as the A800 and H800. But those chips were banned the following year, when the Commerce Department revised the scope of its controls.

While Nvidia’s China revenues almost tripled from 2022 to 2024, they did not keep pace with overall sales growth. In 2022 China accounted for 21 percent of Nvidia’s total revenues. By 2024 that had fallen to 13 percent.

“They wanted no line to be drawn,” recalls another former senior Commerce Department official. “They might have had a better chance of defining the placement of the line with a different approach.”

Several people familiar with Nvidia’s lobbying efforts say the company has aggressively rebutted its perceived opponents. Nvidia representatives frequently refuted arguments by export control proponents in private meetings by dismissing the people as dumb or uniformed, five people told The Wire.

They gave the whole song and dance about how there’s no evidence of diversion. You’d have to be totally uninformed to believe Nvidia’s narrative… They are mostly playing defense and trying to muddy the waters and poison the well.

Samuel Hammond, chief economist at the Foundation for American Innovation

Nvidia executives have also challenged claims that its chips are being smuggled into China, or that the Chinese military is purchasing its chips, despite a growing amount of evidence to the contrary. Huang has said there is “no evidence of any AI chip diversion.”

After Samuel Hammond, chief economist at the Foundation for American Innovation, a right-leaning Washington think tank, wrote a March report on Chinese chip smuggling that was critical of Nvidia, the company asked him for a meeting within an hour. “They gave the whole song and dance about how there’s no evidence of diversion,” he says. “You’d have to be totally uninformed to believe Nvidia’s narrative… They are mostly playing defense and trying to muddy the waters and poison the well.”

In a statement to The Wire, a spokesperson for Nvidia said: “Commercial chip sales pose no more national security threat than uncontrolled products like commercial jetliners and consumer pickup trucks.”

“A FOOL’S ERRAND”

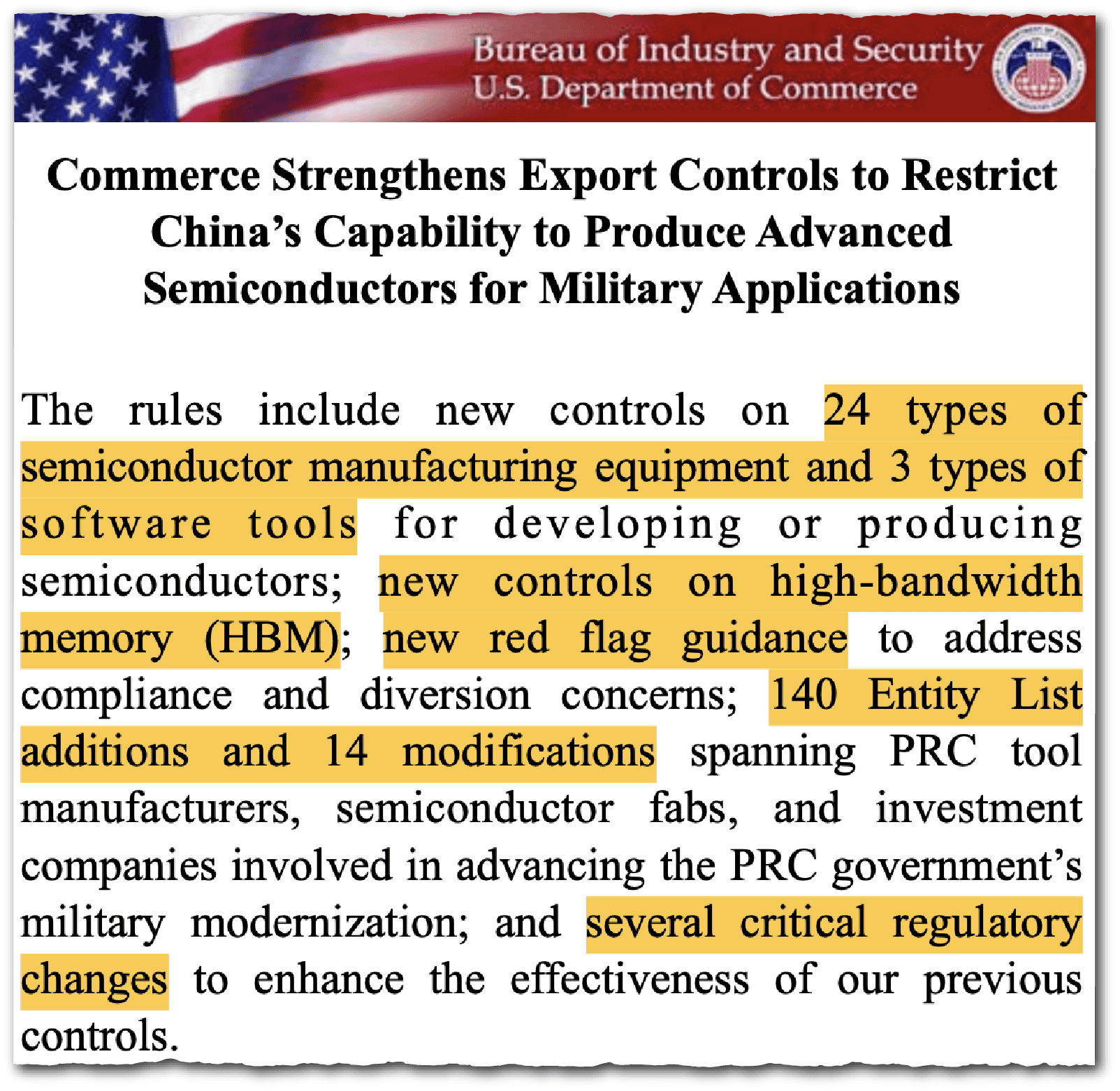

Biden administration officials did not feel like their job was done after the first set of controls came out. In October 2023, Commerce updated them. The ‘clean-up rule’ plugged many of the gaps critics say the original controls had missed, such as banning the A800 and H800 and expanding the restrictions to cover overseas facilities of companies headquartered in China.

For months behind closed doors, officials had debated the appropriate performance threshold for chips that could not be sold to China, according to four former officials. Commerce, led by Secretary Gina Raimondo, proposed allowing Nvidia to sell a chip “basically equivalent” to the A800 before being shot down by the other three agencies and the White House, one person noted, though she favored the geographic expansion and other tightening measures.

Then Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo with Japan’s then Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry Saito Ken, and then Dutch Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation Liesje Schreinemacher (right). Credit: METI, Gina Raimondo

“Trying to hold China back is a fool’s errand,” Raimondo said last December. Raimondo did not respond to a request for comment.

At the same time, Commerce officials increased pressure on allies to match U.S. restrictions. Raimondo, who began to play a larger role in chip negotiations after her Dutch and Japanese counterparts took over their side of negotiations, led the diplomatic squeeze.

Then Commerce Secretary Raimondo on working with allies, Regan Defense Forum, December 7, 2024. Credit: President Reagan’s Foundation

“When I set the rules, I have to make damn sure China can’t just buy this stuff from Japan or Korea or the Europeans, so that’s why we have to work with them,” Raimondo said at the Reagan Defense Forum in Washington last year.

“She was very willing to pressure them, threaten them, drive them to do whatever it takes to get them to do more,” recalls a person familiar with the negotiations. “There was no love lost with the allies if they were not doing what they needed to do.”

The U.S., the Netherlands and Japan disagreed over which companies and tools should be off limits, and whether their nationals should be allowed to service machinery in China. In each arena, U.S. rules were more restrictive.

The Dutch and Japanese did eventually upgrade their controls, but still not as much as the U.S. wanted. Many analysts say that the two allies did so reluctantly. “They definitely are being dragged along by the U.S.,” says O’Laughlin, of SemiAnalysis.

Kazuto Suzuki, a professor of science and technology policy at the University of Tokyo, says Japan’s export controls were primarily motivated by the desire to prevent China from developing AI that could be used for military purposes. But he notes that “it is obvious that we are following American footsteps.”

“China is the golden market. You are just throwing all those profits away,” he adds. “The Japanese government said we can accept this loss but we cannot accept conflict with the United States.”

As Chinese chipmakers and AI companies continued to make progress, a chorus of China hawks ratcheted up pressure on the administration to do more. In 2023, Michael McCaul, Republican chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, published a review of BIS, in which the committee criticized the agency for “too often [putting] economic and commercial considerations of single companies before national security.”

After news broke last October that TSMC may have inadvertently produced chips for Huawei, BIS published a new rule that increased scrutiny of chip fabs. In December it published a different rule further limiting China’s access to high bandwidth memory chips and expanding the application of FDPR to restrict exports of advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment made anywhere in the world — with exemptions for Japan and the Netherlands. And as fears grew in Washington over whether China was buying chips through third countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, officials also rushed out a sweeping and complex new framework for controlling the sale of AI chips worldwide.

For some in the AI industry, it was this “AI diffusion” rule that took Washington’s rapidly expanding regulatory agenda too far. Nvidia issued a public statement castigating the Biden administration.

“In its last days in office, the Biden Administration seeks to undermine America’s leadership with a 200+ page regulatory morass, drafted in secret and without proper legislative review,” wrote Ned Finkle, Nvidia’s vice president of government affairs.

NEW SHERIFF, SAME LAW

Former export control officials agree that the hardest thing about imposing controls is getting the technical parameters right.

“Drawing the line [between] what to control and what not to control is a fraught process,” says Thea Kendler, who served as assistant secretary for export administration at BIS under Biden. “We did the best we could with the information we had, but that information changed over the time and resulted in the need to constantly update.”

The more U.S. tech is out there, the higher the probability that tech is diverted to China, which cuts against the goal of restricting China’s access to the most advanced tech. [But] the more you restrict, the more you create potential market vacuums that Chinese companies could theoretically fill in.

Michael Horowitz, a Biden Defense department official who worked on the AI diffusion rule

The change in administration was widely expected to trigger a review of Commerce’s strategy.

Michael Horowitz, a Biden Defense department official who worked on the AI diffusion rule, says that at the end of 2024 “there was a bipartisan consensus that tech diversion to China was the biggest risk.” Now, he adds, “the Trump administration is looking at these issues with fresh eyes.”

The new administration has been more forceful in setting expectations that allies align their export controls with America’s, according to an official who worked under both presidents.

But a key point of disagreement has been over the diffusion rule, which many in the new administration believe went too far in limiting U.S. companies’ abilities to market their chips abroad.

“The more U.S. tech is out there, the higher the probability that tech is diverted to China, which cuts against the goal of restricting China’s access to the most advanced tech,” Horowitz says. But, he adds, “the more you restrict, the more you create potential market vacuums that Chinese companies could theoretically fill in.”

Inside the second Trump administration, David Sacks, the president’s “AI czar,” emerged as a vocal critic of the Biden regulations.

“TO WIN THE AI RACE, THE BIDEN AI DIFFUSION RULE MUST GO,” he posted on X in May. “Yes, we must take aggressive steps to prevent advanced semiconductors from being illegally diverted into China. But that goal should not preclude legitimate sales to the rest of the world as long as partners comply with reasonable security conditions.”

Five days later, the Commerce Department announced it had rescinded the rule.

In July, the Trump administration released its own AI plan, outlining its vision for achieving “global dominance” in the technology. The plan’s introduction, signed by Sacks, science advisor Michael Kratsios and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, emphasizes a “need to establish American AI — from our advanced semiconductors to our models to our applications — as the gold standard for AI worldwide.”

The plan calls for an export control strategy that is, on paper, similar to the Biden playbook. It focuses more on the supply chain, recommending new restrictions on components used to make semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and does not call for removing existing controls.

“The highest-end semiconductors need to continue to be export-controlled and not allowed into China,” Kratsios said at a CSIS event in July. “What’s important is that we’re not necessarily cutting everything off from China.”

FROM NATIONAL SECURITY TO ECONOMIC LEVERAGE

But even if the controls themselves are not changing, the motivation behind them is. The Biden administration consistently argued that slowing China’s AI advancements was necessary to hinder its military modernization. Under Trump, they are no longer just about national security, but are increasingly viewed as economic leverage, especially in trade negotiations.

Dean Ball, a lead writer of Trump’s AI Action Plan who left the administration in August, does not view export controls as driven by stopping the Chinese military from using advanced AI. “That’s a nice lie people in DC have told themselves,” he says. What the controls are really aimed at, he adds, is economic competition: “If the PLA wants to use AI to do something, they’re going to do it regardless of whether the H20 is allowed in China. This is about normal consumer and enterprise uses of AI.”

This change in how export controls are regarded was reflected in the Trump administration’s willingness to put newly imposed controls up for negotiation in recent trade talks with China, especially in return for access to rare earth minerals.

In May, Washington slapped export controls on software used to design chips, in retaliation against China’s moves to suspend exports of rare earths and related magnets to the U.S. It then lifted those restrictions in July, after Beijing agreed to resume some rare earth sales.

“Export controls until now have been adamantly defended as [essential to] national security,” says Matt Axelrod, the assistant secretary for export enforcement at BIS during the Biden administration. “Other countries, particularly China, make the claim that the U.S. uses export control for economic leverage, and the U.S. has consistently made the case that’s not true.”

Meanwhile, companies on either side of the Pacific are still waiting for the Trump administration to translate its AI Action Plan into policy.

“There was a pretty unified sense that the Trump administration was going to come in and quickly do various things they argued the prior administration had failed to do and generally be more stringent on export controls, especially with respect to China,” a third former Commerce official told The Wire. “It seems they have taken some significant steps, at least behind the scenes, but we’re also seven months in and many of the major proposals have not materialized, creating potential gaps in effectiveness.”

Export controls until now have been adamantly defended as [essential to] national security. Other countries, particularly China, make the claim that the U.S. uses export control for economic leverage, and the U.S. has consistently made the case that’s not true.

Matt Axelrod, the assistant secretary for export enforcement at BIS during the Biden administration

The inaction, several officials who worked in the Trump administration told The Wire, stems chiefly from the exodus of expertise from the administration.

In April Trump fired David Feith, the senior director for technology and national security on the NSC, after a meeting with far-right activist Laura Loomer. Trump himself had appointed Feith months earlier. The administration later closed the whole directorate — which played a key role in architecting the export controls under Biden — and replaced it with a team focused on supply chain security.

“The guidance and balanced counsellor role of the NSC is either inoperative or, at best, really starved,” says Garnaut Global’s Tobin.

The NSC did not respond to a request for comment.

In July, the State Department closed the Office of the Special Envoy for Critical and Emerging Technology, which played a role in coordinating chip and AI policy. Career officials were fired and foreign service officers reassigned. “Even the political appointees were apoplectic,” says a former State Department official.

“The reorganization has streamlined decision-making and has reduced redundancies without compromising core capabilities,” a State Department spokesperson says.

Under Trump, BIS has taken restrictive measures like pausing licenses to restricted entities. The bureau is also in line to receive a 59 percent increase in funding, if Congress agrees on a proposed budget.

But BIS has also lost at least 30 percent of the staff that work on export control policy and license applications to DOGE cuts and resignations; license approvals have slowed to a crawl. Three people familiar with the matter say the bureau has been sidelined, with its top official, Under Secretary Jeffrey Kessler, having limited access to Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick. Major administration policies such as the chip design software export controls were drafted without the involvement of BIS staff.

“Decision making on AI policy became increasingly centralized within a few decisionmakers in the White House and Commerce Department,” particularly Lutnick and Sacks, says the former State Department official.

Whether Lutnick and Sacks are on the same page is a different question. In June the Commerce secretary told lawmakers that China’s chipmaking capacity this year would only be around 200,000 advanced chips, far short of domestic demand. But, in a post on X last month, Sacks criticized the Biden administration’s “overzealous regulations” for being “predicated on the assumption that China couldn’t produce enough chips for export.”

The Bureau of Industry and Security, Department of Commerce, and White House did not respond to requests for comment.

At Nvidia, Huang has been able to cut through the bureaucratic thicket and appeal directly to the president. At the press conference on August 11, Trump described the H20 chip as “an old chip” and “obsolete” — language, two analysts say, that is distinctly reminiscent of Nvidia’s private talking points.

A Trump administration official who spoke on the condition of anonymity says the optics of the H20 ban are worse than the reality. “The process has generated controversy, but we still controlled a chip that was previously uncontrolled and required licenses in a way that the previous administration did not.” (Biden administration officials maintain they would have gotten around to banning the chip.)

Administration officials have yet to codify Trump’s 15 percent deal with Nvidia and AMD, even as BIS has approved H20 licenses for some Chinese customers, paving the way for Nvidia to ship some chips to China without paying the commission, Colette Kress, Nvidia’s chief financial officer, said in an August earnings call.

“Until the previous administration, U.S. export policy wisely focused on military products while promoting American prosperity,” the Nvidia spokesperson said. “The overbroad export controls of the previous four years undercut American leadership, deprived the American public of billions of dollars in tax revenue and enriched Huawei, without a single benefit in return. America rightly chose to turn the page on that failed approach and move forward with the new Administration’s AI Action plan.”

A stronger test of the Trump administration’s willingness to hold steady on export controls will be whether it allows Nvidia to sell an even more advanced chip to Chinese companies. Huang said last month that he is hoping to do so and is “optimistic” a deal can be reached.

At the press conference in August, Trump suggested he would be open to approving a degraded chip with “30 percent to 50 percent” of its performance curtailed.

But even a 50 percent degraded version of Nvidia’s next generation chip, the B300, would outperform Nvidia’s current state-of-the-art H100 chip, and would vastly exceed the thresholds set by the Biden administration’s 2023 controls, according to Lennart Heim, a researcher at RAND.

Khan, who helped design the Biden controls, says that to allow sales of such a chip is to give up on chip export controls, because Chinese companies could buy enough degraded B300s to compensate for their limits. “Selling an unlimited number of those is tantamount to canceling the chip control policy,” he says.

Noah Berman is a staff writer for The Wire based in New York. He previously wrote about economics and technology at the Council on Foreign Relations. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe and PBS News. He graduated from Georgetown University.

Eliot Chen is a Toronto-based staff writer at The Wire. Previously, he was a researcher at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Human Rights Initiative and MacroPolo. @eliotcxchen