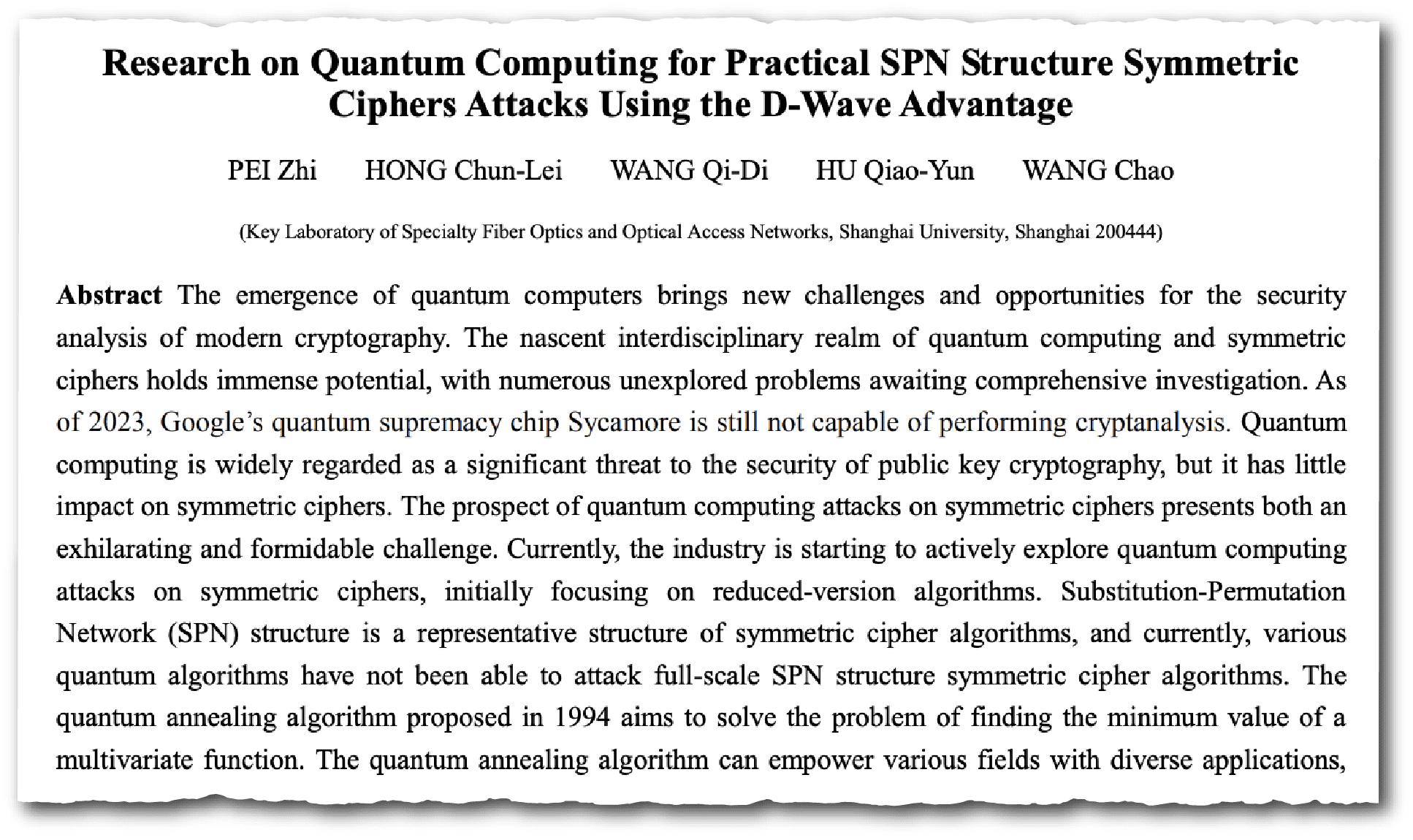

In October, researchers at Shanghai University published a paper in the Chinese Journal of Computers that triggered a tsunami of panic across the Pacific. Using a quantum computer developed by D-Wave, a Canadian company, the researchers said they had developed a hybrid method and successfully executed attacks on three encryption algorithms. “This marks the first practical attack on multiple full-scale SPN structure symmetric cipher algorithms using a real quantum computer,” they said.

The South China Morning Post, which first reported on the paper, summed up the achievement in its headline: “Chinese scientists hack military grade encryption on quantum computer: paper.” A flurry of subsequent headlines touted the “breakthrough,” and a fear began to form that China had taken a considerable step towards “Q-Day” — the moment when quantum computers will be powerful enough to mosey right into all currently encrypted communications.

In other words, it looked like the U.S. government’s nightmare scenario.

“People were panicked because the researchers reported findings that suggested the advent of encryption breaking quantum computers was much closer than almost anyone had predicted,” says Dan Goodin, senior security editor at the tech publication Ars Technica. “If the findings were valid, it meant that medical and banking records, TLS keys for websites, and military secrets could all be exposed before there were any quantum-resistant replacements in place.” (The National Institute of Standards and Technology, under the Department of Commerce, has set out a plan to help federal agencies, tech providers and others move their systems to quantum-resistant cryptographic standards by 2035.)

Cryptography Standards’, released November, 2024. Credit: NIST

Of all of China’s quantum ambitions, “that is definitely the threat that is most concerning,” says Sam Howell, an associate fellow with the Technology and National Security Program at the Center for a New American Security. “At the forefront of all policy makers’ minds is: What if China develops a quantum computer powerful enough to crack public key encryption?”

And yet, there is no indication that China is anywhere close to achieving that.

Despite the reaction to the Shanghai University researchers’ findings, the extent of their attack — searching “integral distinguishers up to 9-round” — is something that is known to be possible with classical computers. And the research didn’t prove that quantum computers would be any better for the task. David Jao, a professor who studies post-quantum cryptography at the University of Waterloo, says that the researchers did not so much crack the lock as develop a new lockpick. “The breakthrough was that they were able to do it with a quantum computer, which I guess is cool, if you want to see quantum computers do tricks like a show pony,” Jao says.

(SCMP, which was presumably told the same thing at some point, quietly removed its reference to the Chinese scientists’ achievement on “military grade” encryption.)

The Western fear surrounding China’s quantum advances is compounded by the logic-defying nature of quantum technologies. The field is both otherworldly and “spooky,” as Albert Einstein remarked, and its potential capabilities extend far beyond what most of us can even fathom. The concept of quantum catalysis, for instance, is “similar to Star Trek,” Lu Chao-Yang, a leading Chinese quantum physicist at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) explained in an interview. “You can travel somewhere else without physically transporting the object.”

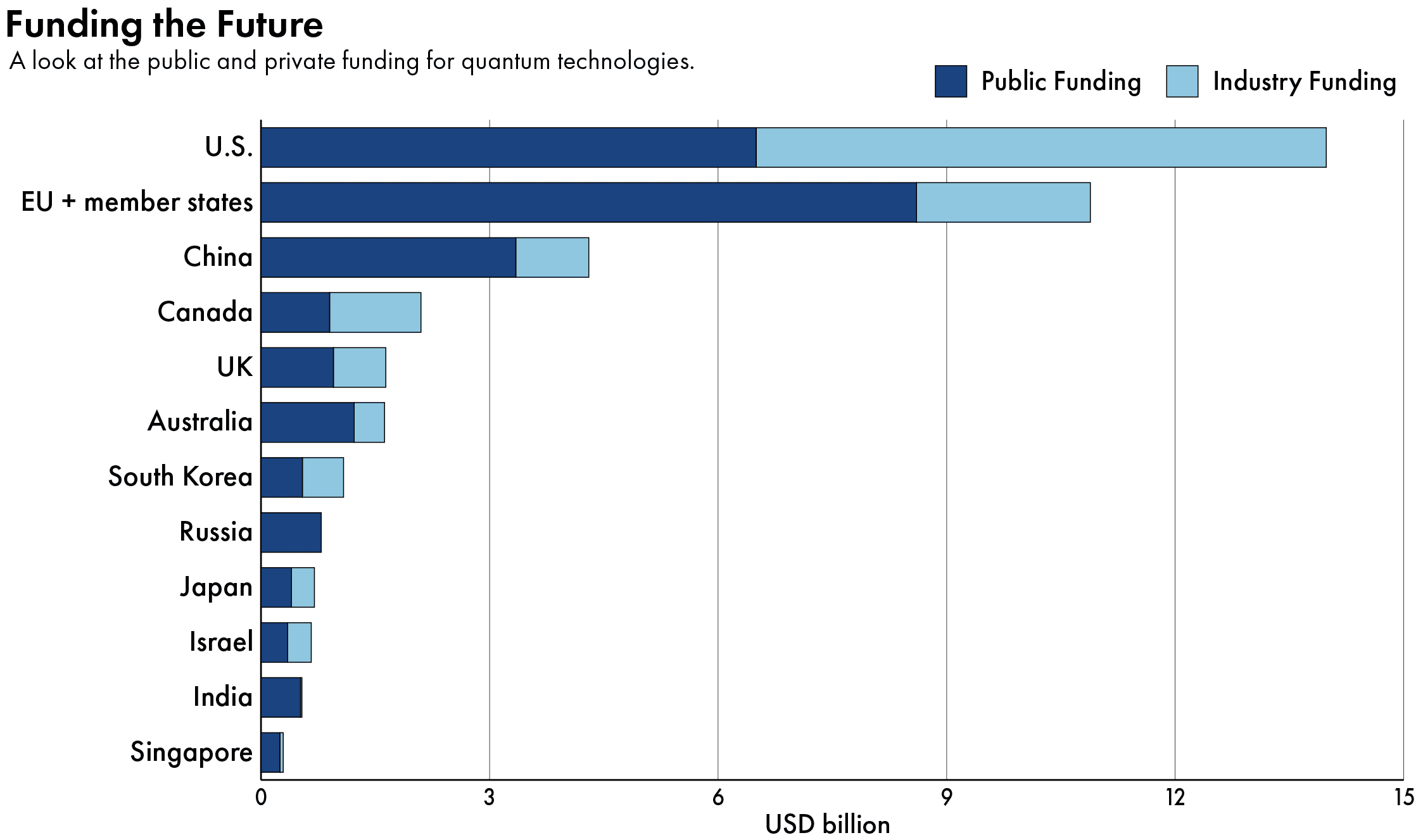

In other words, significant advances in quantum promise to upend every industry from material science to finance to healthcare to warfare. And a prominent narrative is that China is leaping ahead while the U.S. risks falling behind. In a 2022 report, for instance, McKinsey wrote that China has committed $15.3 billion to quantum computing investments — “more than double that of EU governments ($7.2 billion) and eight times what the United States has pledged to spend ($1.9 billion).” Other consultancies have put China’s investment into quantum at $25 billion, fueling the notion that China is outspending every other country in the world.

There’s a decent chance that quantum technology will be transformative on the level of the internet; there’s also a decent chance it will just completely fizzle out and won’t actually lead to commercial applications of any kind.

Edward Parker, a physical scientist at RAND Corporation

But much like the Shanghai University paper, China’s investment into and advances in quantum technologies deserve a closer look. The $15–25 billion figure, for instance, is likely padded significantly by reports that China spent $10 billion in 2017 on the national lab for quantum information sciences in Hefei, which some Chinese media outlets hailed as the largest such facility in the world. But while widely cited, the $10 billion figure is extremely difficult to verify; an official release from the provincial government stated that the total investment for the first phase of construction was less than $1 billion. In a 2022 report, RAND researchers said they could not find reference to the $10 billion figure in Chinese-language media. “We believe that it stems from a common translation error involving the different structures of the English and Chinese counting systems,” they wrote.

Lu, the Chinese scientist who is part of the lab, has also repeatedly told Western media that these figures don’t make sense. “I think Google alone maybe will have more than we invest for the whole country,” he told New Scientist in 2021. “We’re not moving so fast in terms of the national project because not all scientists in China are convinced. We’re still waiting for the real money. If there’s a further delay, we’ll definitely be left behind.”

China, of course, is likely not publicizing all of its investment into quantum, which is seen as a dual-use technology with military applications. But Olivier Ezratty, author of the book Understanding Quantum Technologies, stresses that “the misleading communication is often not coming from China itself. In the U.S., consultants and others are amplifying the threat from China because it justifies having more investment in the United States.”

To be sure, China has made significant strides. Thanks to mega-projects such as its quantum satellite constellation and ground-based network, the general consensus is that it has a lead in quantum communications, and the country could close the gap in quantum computing in the future.

But despite the promises it holds, research on quantum is still at such an early stage that there remains a lot of uncertainty. Even China’s perceived headstart in quantum communications might not hold, says André König, chief executive of Global Quantum Intelligence, a New York-based market data provider: “It’s like saying you’re ahead in a marathon after three or four kilometers.”

“No one knows where quantum is going anywhere in the world,” adds Edward Parker, a physical scientist at RAND Corporation. “There’s a decent chance that quantum technology will be transformative on the level of the internet; there’s also a decent chance it will just completely fizzle out and won’t actually lead to commercial applications of any kind.”

While the U.S. wants to be prepared, researchers and experts in the field are increasingly pushing back against the idea that China’s quantum threat is imminent or existential. Instead, they argue, a better understanding of China’s quantum scene and its achievements is critical. As Brian Siegelwax, author of the newsletter The Quantum Dragon, put it after reviewing China’s “most capable” superconducting quantum computer last January: “What are they proud of and what are we fearing?”

THE TWO GUOS

Most of China’s quantum enterprises are concentrated on a single road in the city of Hefei, earning it the nickname of Quantum Avenue. Among them is the 7-year-old startup Origin Quantum, which is the proud owner of the quantum computer that Siegelwax reviewed as less-than-capable last year.

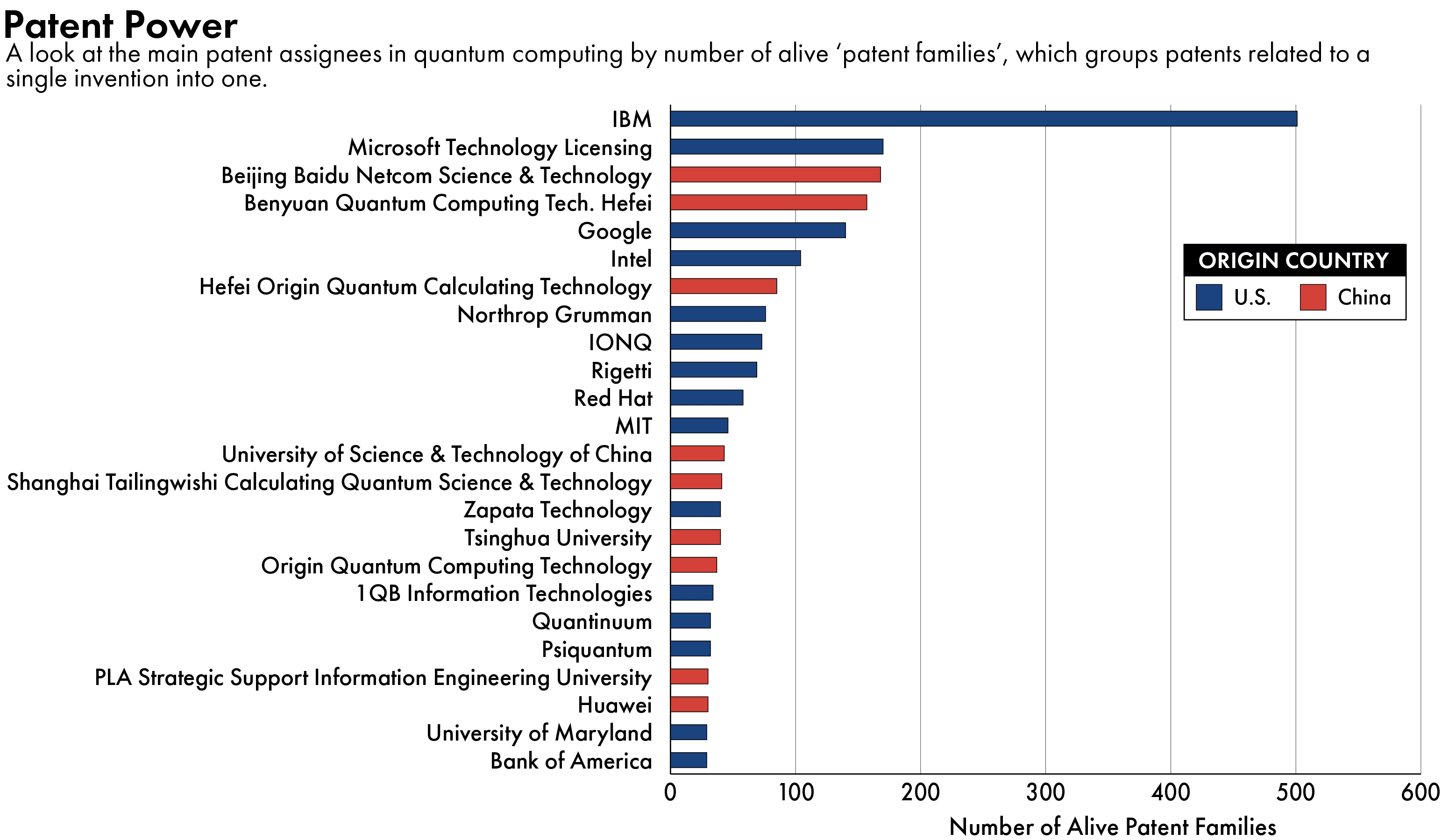

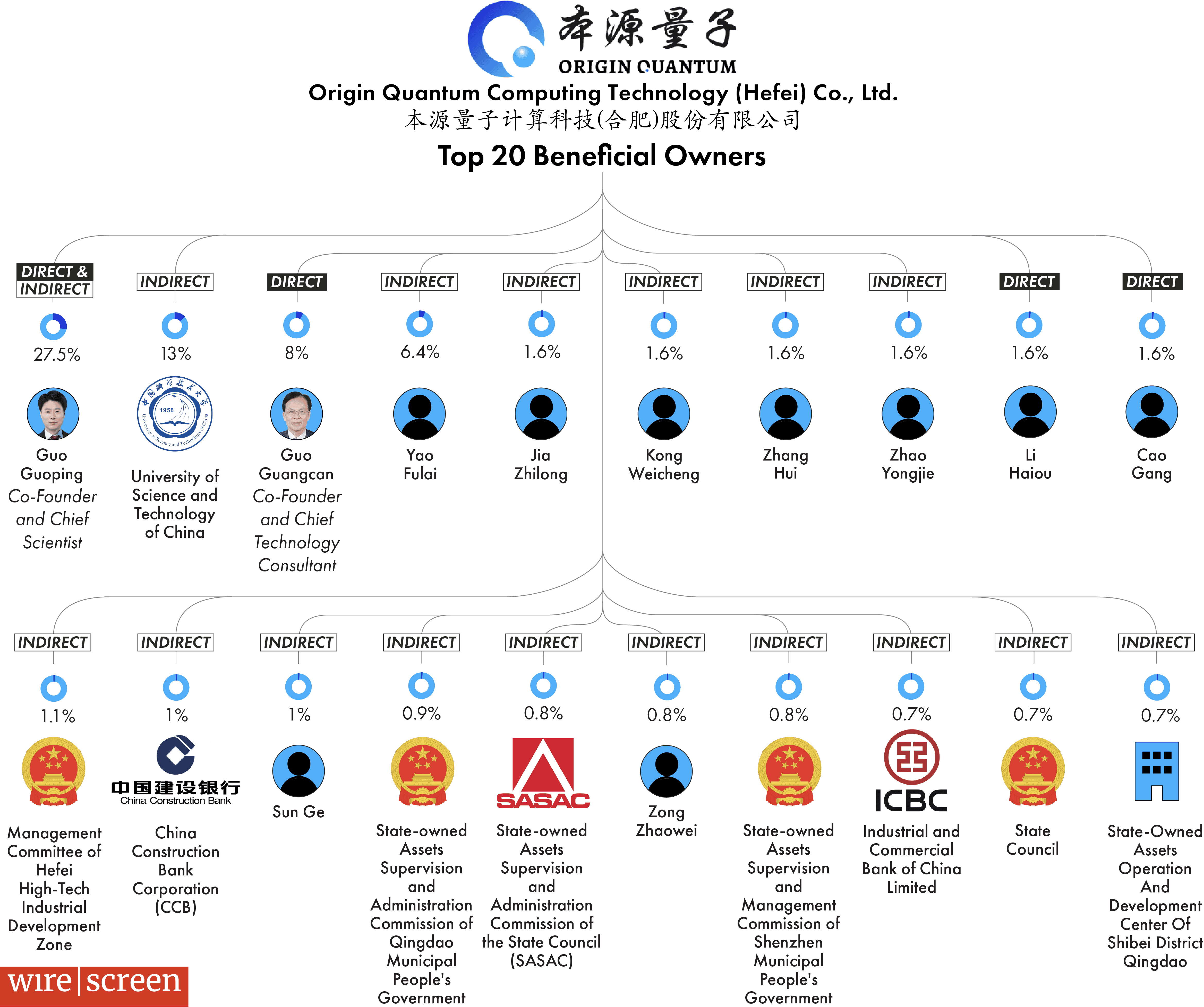

Origin Quantum is, by many metrics, the quantum leader in China’s private sector. The company said it delivered a 24-qubit quantum computer to an unspecified user in 2021, making China the third country after Canada and the U.S. to sell such a device. The following year, it raised 1 billion yuan ($148 million) from mainly state-owned venture firms in the largest funding round disclosed by a Chinese quantum company. Then, last January, it debuted Wukong, its 72-qubit chip quantum computer online, offering free trials to global users. The company said this month that Wukong has been accessed 19.6 million times by users from 139 countries, who completed some 330,000 quantum computing tasks.

“It seems pretty obvious that Origin Quantum is one of the stronger players in China,” says Jeroen Groenewegen-Lau, an analyst at Mercator Institute for China Studies. “But that doesn’t really help us with assessing how valuable their IP actually is or how relevant their breakthrough is.”

Siegelwax, who specializes in the nitty gritty of quantum computers, endeavored to find out. For his newsletter, he has run basic tests on over a hundred quantum platforms and utilities. He found that Wukong had poorer performance — such as lower qubit connectivity and higher error rates — than other systems, and Siegelwax says that when he accessed it during daytime in China, Wukong only had one user in line, not the throngs the company has claimed. By comparison, IBM’s machines often have long queues of up to hundreds of users.

“It [offers] free access to machines that presumably cost a ton of money, but they are qualitatively poor enough that there is no reason to use them,” Siegelwax told The Wire China.

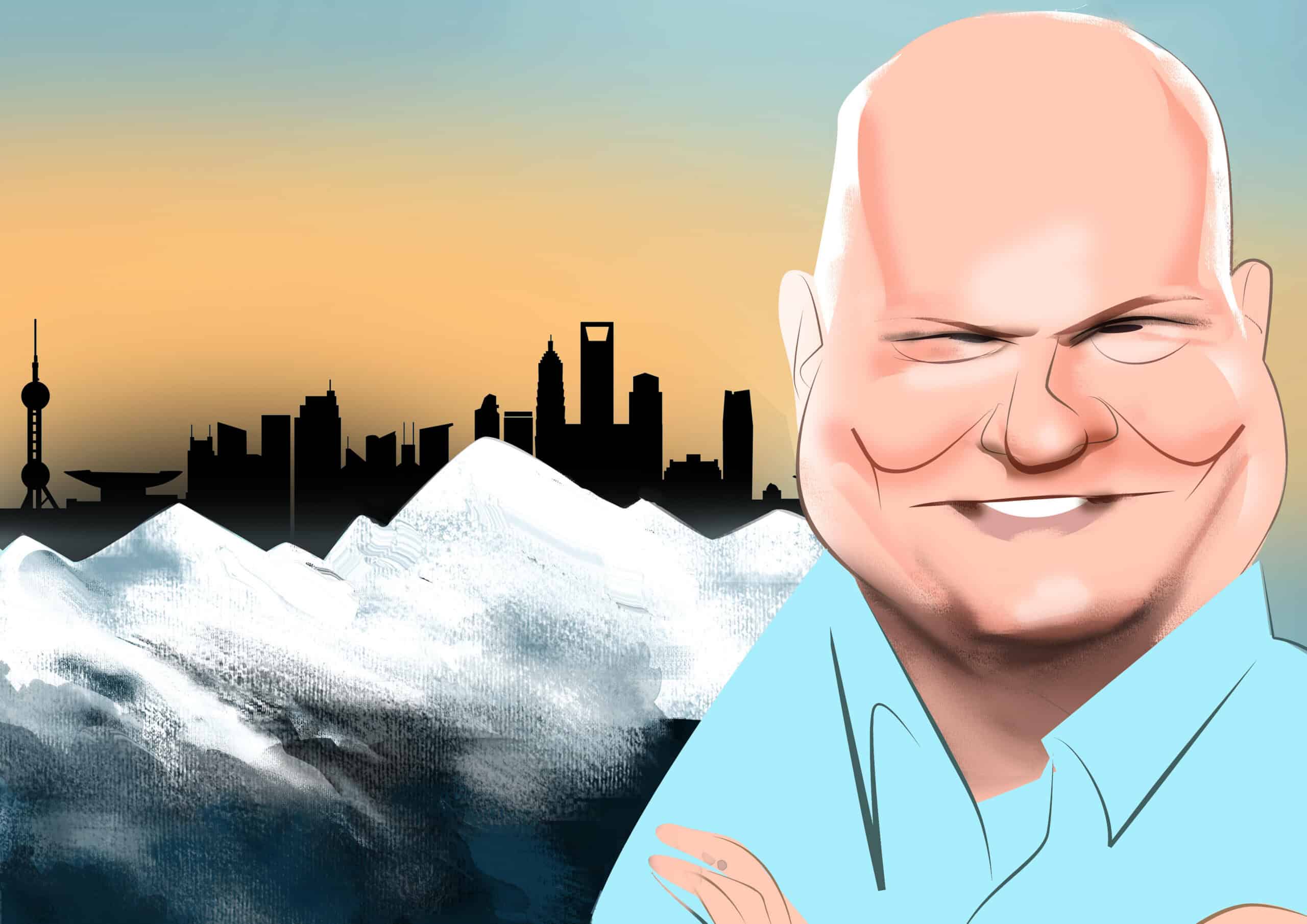

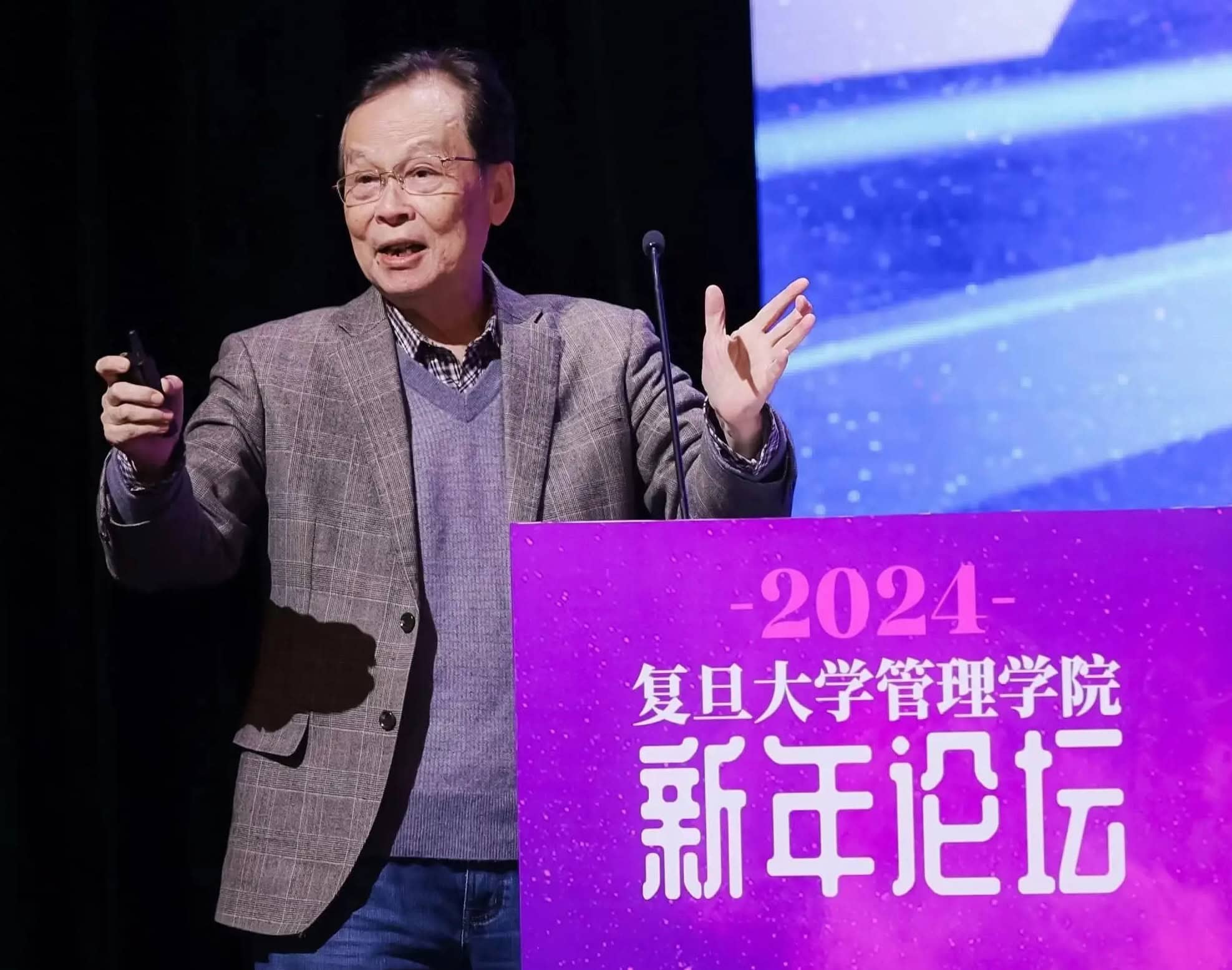

Origin Quantum did not respond to requests for comment, but it’s not difficult to imagine this review bruising the pride of its 82-year-old founder, Guo Guangcan.

As one of China’s first quantum physicists, Guo has long attached a strong nationalistic mission to his work. Emblazoned on the company’s wall, for instance, is the slogan: “Accelerate the pace of technological self-sufficiency, solve ‘chokepoints’ imposed by foreign countries.” When a correspondent from The Economist visited recently for a scheduled interview, the company was so alarmed by the sight of a foreigner that it called the police.

In other words, while many scientists bemoan the politicization of fields like quantum, Origin Quantum has both embraced and benefited from it.

“For his generation of Chinese scientists who came of age in the Mao era, science and technology was for national defense and strengthening,” says Yangyang Cheng, a fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center and a USTC alum. “And in today’s China, leaning into certain types of rhetoric in a lot of the fields of emerging technologies is not just a way to raise prestige, it is also a marketing strategy.”

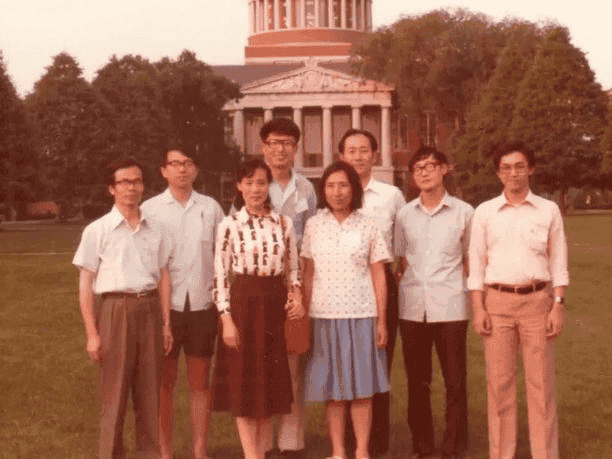

Indeed, Guo Guangcan comes by it honestly. As a student at USTC in 1963, he became mesmerized by quantum mechanics. But in the early 1980s, when Guo was granted a rare opportunity to be a visiting scholar at the University of Toronto, he was stunned to discover that China was 20 years behind the West. When he and seven other Chinese scholars — including Deng Xiaoping’s youngest son, Deng Zhifang — met up at a quantum conference in New York, they decided something had to be done. “We made a pact that when we returned to the country, we must jumpstart quantum development in China,” he recalled in an interview with the Chinese state broadcaster earlier this month. “That was the promise.”

In 1983, Guo returned to China armed with boxes of photocopies of research papers he had made in the University of Toronto library. Eventually, he compiled them all into China’s first textbook on quantum optics. But many scientists in China at the time still regarded quantum as a pseudo-science, and Guo told Nature in 2023 that he was “lonely and helpless” for years.

Around 1998, Guo found a kindred spirit: a student, Guo Guoping (unrelated), who would eventually become Origin Quantum’s co-founder and chief scientist. In the company’s lore, the two often reflect on their humble beginnings, including how they purchased second-hand equipment from U.S. universities to build their first laboratory and how their team took turns using the sole computer — an Intel 386 — in the lab. Guo has said his application for national funding was rejected three times before 2001, when he finally received $3.42 million — half the amount he had asked for.

Guo was shrewd, however, and more than a decade later, he saw an opening for more national support. In 2013, when the Edward Snowden leaks triggered Chinese leaders’ anxiety about their vulnerability to cyberattacks and espionage, Guo was quick to propose quantum cryptography as an answer. “Once the application of quantum keys is realized, it can guarantee that messages transmitted through optical fibers wouldn’t be eavesdropped on,” he told China Science Daily that November.

…no country — not China, not the U.S. — can do quantum alone, it is too complex from a hardware point of view, a mathematical algorithm point of view, and also a supply chain point of view.

André König, chief executive of Global Quantum Intelligence, a New York-based market data provider

Quantum shot up China’s list of priorities after the scandal, but Guo’s ambitions didn’t end there. In 2017, a year after China launched the world’s first quantum communication satellite Micius, the two Guos founded Origin Quantum as a private company, setting out to turn more than a decade of research into practical quantum computers. At the time, most of China’s quantum efforts were still led by research institutions, but they were concerned that China could lose the market to first-movers such as tech giants Google and IBM. “Much like the Windows operating system, if a habit is formed, it would be very difficult to replace it with domestic operating systems,” Guo Guoping told The Paper in 2023.

The two Guos have been rewarded for that vision. In 2023, Guo Guoping became a deputy to the National People’s Congress, the national legislature. Meanwhile, Guo Guangcan is finally realizing his lifelong dream and is eager to pass the torch to a new generation: Origin Quantum’s research department had a team of over 200 scientists in 2023 with an average age of 26.

Guo Guangcan discusses quantum computers during a CCTV interview, February 2, 2025. Credit: CCTV

“Guo Guangcan deserves a lot of credit for what was developed [in China],” says Barry Sanders, a professor at the University of Calgary in Canada, who knows Guo because he spent over a decade as a visiting professor at USTC. Yet there’s still “a big question for China as to how much do you want to develop everything indigenously, versus how much benefit there is through the training that goes on outside the country?”

THE MARATHON

Accurately gauging the quantum threat from China — and thus America’s approach to it — remains one of the most tricky elements in the U.S.-China tech competition, not least because of the parade of “breakthroughs.” In one of the most controversial examples, a December 2022 paper from Tsinghua University and other Chinese institutions claimed to have found a new method that could potentially break RSA-2048, a public key commonly used for encrypting emails. Similar to the Shanghai University paper, these claims sent shockwaves across the cryptographic research community before they were eventually debunked. In his blog, Scott Aaronson, director of the quantum information center at the University of Texas, described it as “one of the most actively misleading quantum computing papers I’ve seen in 25 years.”

China is not alone in producing papers that hype up findings. “Posting nonsensical claims and hugely exaggerating your progress is something that every country does,” Parker, of RAND, says. “Not a lot of people really understand [quantum]. So it’s easy to make claims that are very hard to verify and seem superficially plausible.”

But the West’s often disproportionate reaction to Chinese findings underscores two developments: first, just how isolated Chinese scientists have become from the global community; and second, how easy it is to misinterpret quantum developments when they’re seen solely through a geopolitical lens.

The securitization of the field can disrupt academic collaborations, which means there are fewer means of understanding the status of advances in China, says Elsa Kania, an adjunct senior fellow with the Center for a New American Security: “When there’s increased secrecy and less transparency, that makes misperception or misinformation more likely to occur.”

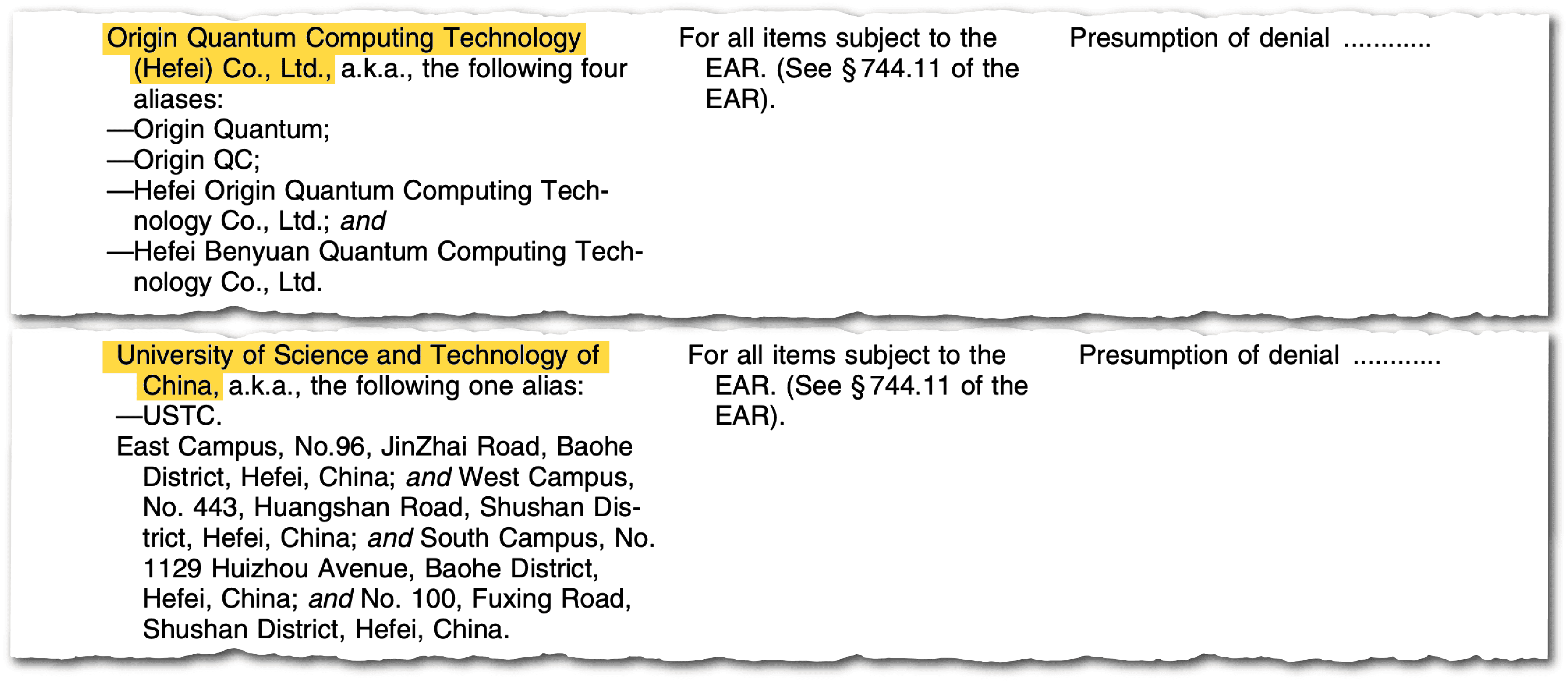

After both the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent U.S.-China tensions, foreign researchers began to draw scrutiny for any work they do in China, while fewer Chinese quantum scientists are showing up to global conferences. As early as 2021, the U.S. imposed export controls on a handful of Chinese quantum institutions, and it drastically expanded the scope in May last year by adding 22 more to the Department of Commerce’s entity list, including Origin Quantum and USTC. “Almost all of China’s core strength in quantum information research has been listed,” Yin Zhangqi, a physicist at the Beijing Institute of Technology, told SCMP.

Elias X. Huber, a Yenching Scholar at Peking University who has studied China’s quantum landscape, notes that this ‘decoupling’ could hurt the West’s quantum ambitions as well. Given how far we are from practical applications of quantum, the U.S. and Europe still have “a lot to gain from sending students to China, from trying to participate in the Chinese quantum development in a way that benefits them.”

The 2022 RAND report by Parker and others has argued the same: It recommended U.S. policymakers not impose export controls yet, noting that it would impede the international collaboration crucial to driving scientific advancements in quantum.

A completely bifurcated quantum industry, Huber adds, will not only make it “much harder to have something equivalent to AI safety dialogues in the future,” but it will also mean the U.S. has “very little leverage [over China] because the supply chains are separated.”

Chinese companies like Origin Quantum, which has aimed to be self-sufficient right from the start, are unconcerned with such outcomes. In fact, the company wore the U.S. sanction as a badge of honor and added it to their social media profile. “I see an increasing convergence of ‘Chinese strength’ in the quantum computing industry in China, which fills me with confidence in the self-reliance and improvement of China’s quantum computing technology,” Guo Guangcan told Global Times last July. “The U.S. blockades will only push our nation to accelerate quantum technologies.”

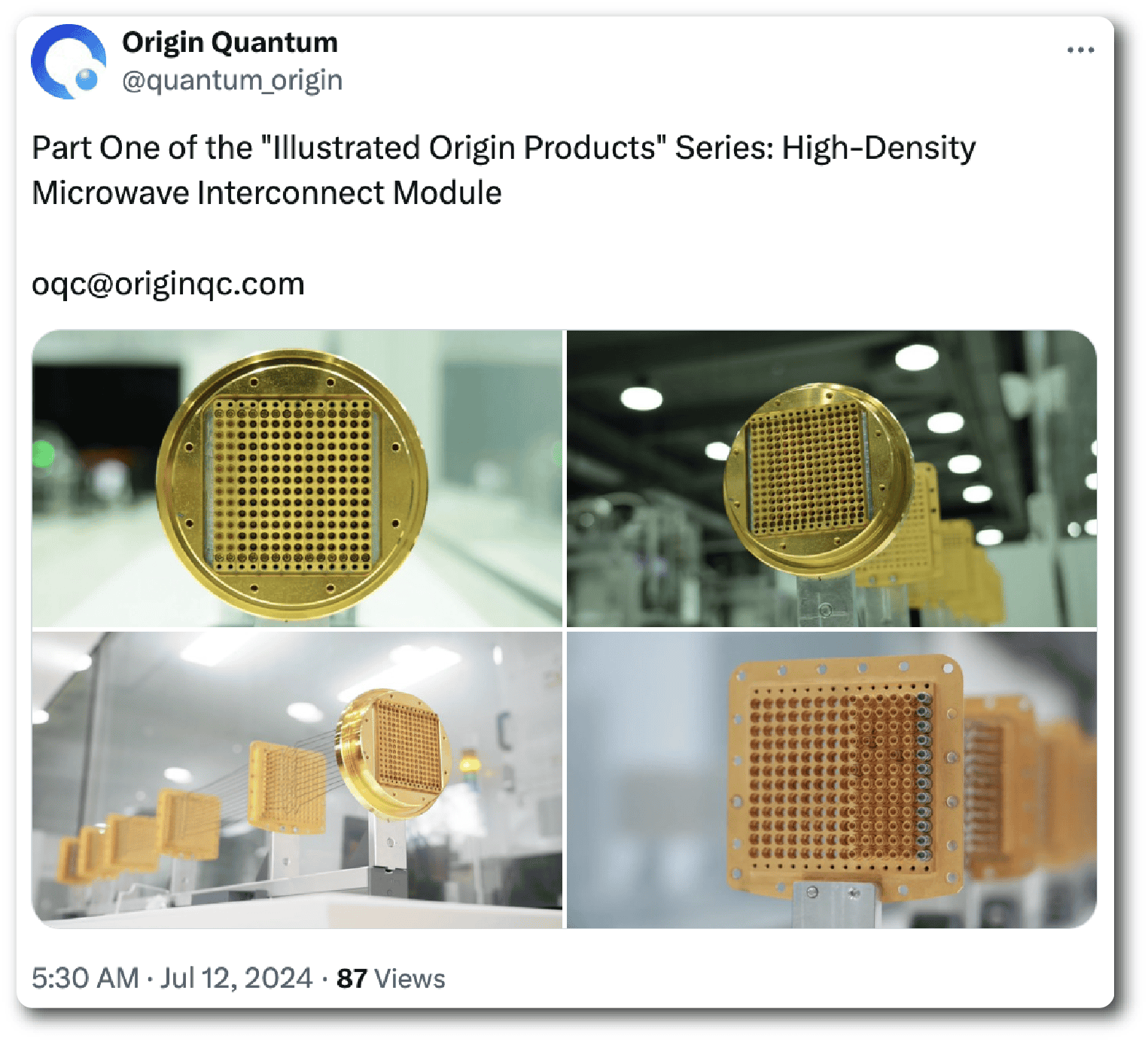

Days after being sanctioned by the U.S., Origin Quantum announced that it was able to produce the “high-density microwave interconnect module” — an essential component for transmitting data — domestically, overcoming its reliance on a Japanese company for one of its parts. A research center cofounded by Origin Quantum has also helped develop a refrigerator needed for keeping superconducting quantum chips in near-absolute zero temperature. Although the Chinese refrigerator is not as sophisticated as the ones by the leading Finnish company Bluefors, says MERICS’s Groenewegen-Lau, it was still a breakthrough in an area that was once thought to be a potential chokepoint.

To some, it brings to mind China’s recent advancements and innovation in semiconductors and AI, despite American export controls. “It really adds additional incentives to all the players — commercial ones, but also researchers — to work together to overcome these bottlenecks with indigenous development,” Huber says.

A decade ago, a company in China could develop and compete on the basis of quality and price. Now it’s not like that. There are questions about whether the technology is secure, if it has back doors and if the price is fair.

Barry Sanders, a professor at the University of Calgary in Canada

But there could be a limit. As some note, building a quantum computer is inherently a global effort.

“We believe that no country — not China, not the U.S. — can do quantum alone, it is too complex from a hardware point of view, a mathematical algorithm point of view, and also a supply chain point of view,” König says.

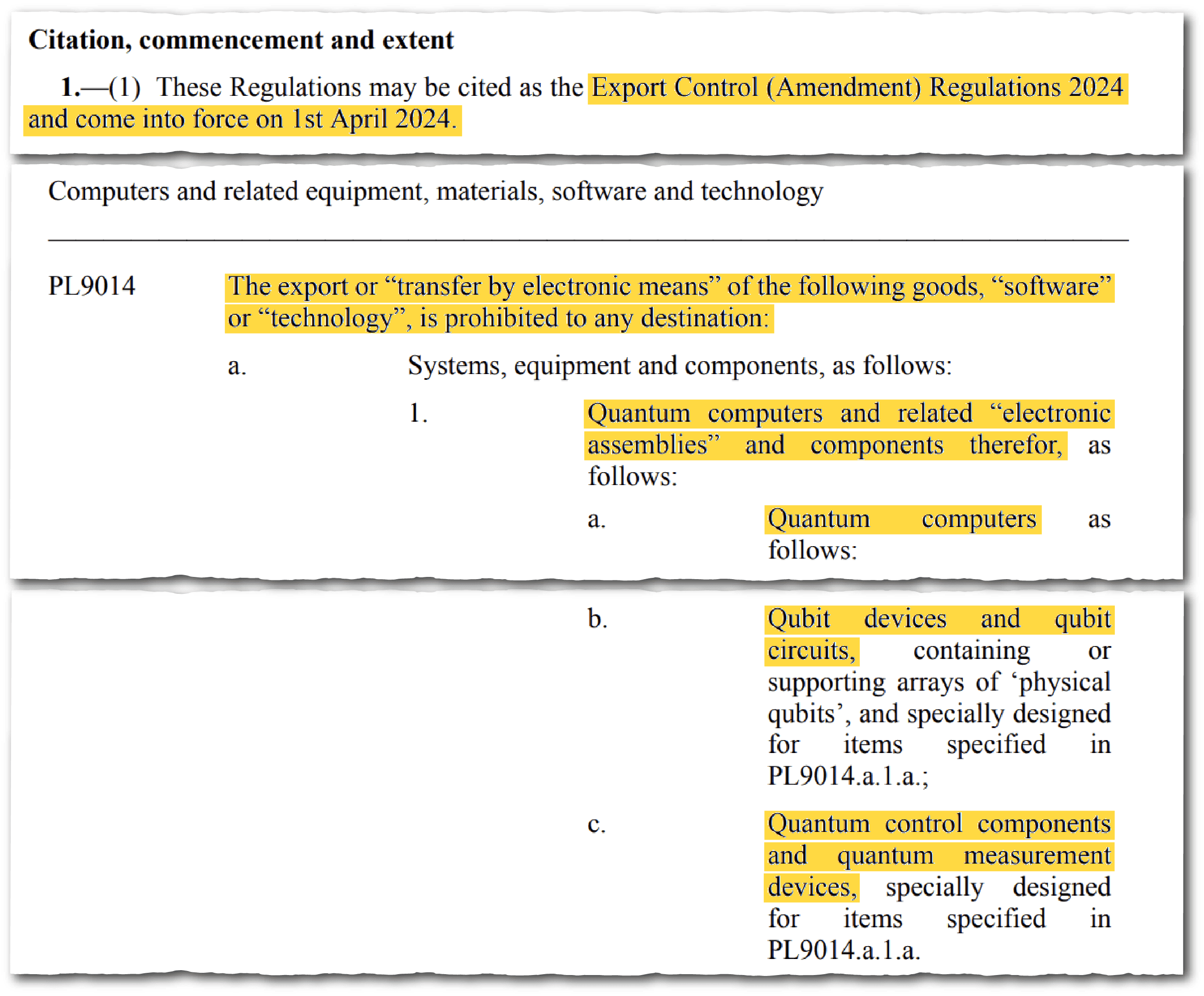

Indeed, Origin Quantum’s side-stepping may only get more difficult as export restrictions become a multilateral effort. Quantum computers have a complex supply chain that is currently spread out across the world; not a single continent has a full stack, let alone a country or a company. France, Spain and the Netherlands are among the EU countries that have introduced export curbs on quantum related technologies in recent years, and the UK followed suit in April, extending restrictions to cryogenic equipment essential for cooling quantum processors.

There’s also the question of how far companies like Origin Quantum can get if they don’t have global market access. “A decade ago, a company in China could develop and compete on the basis of quality and price,” says Sanders. “Now it’s not like that. There are questions about whether the technology is secure, if it has back doors and if the price is fair.”

Within China, there are also voices pushing back against the growing geopolitical divides in quantum.

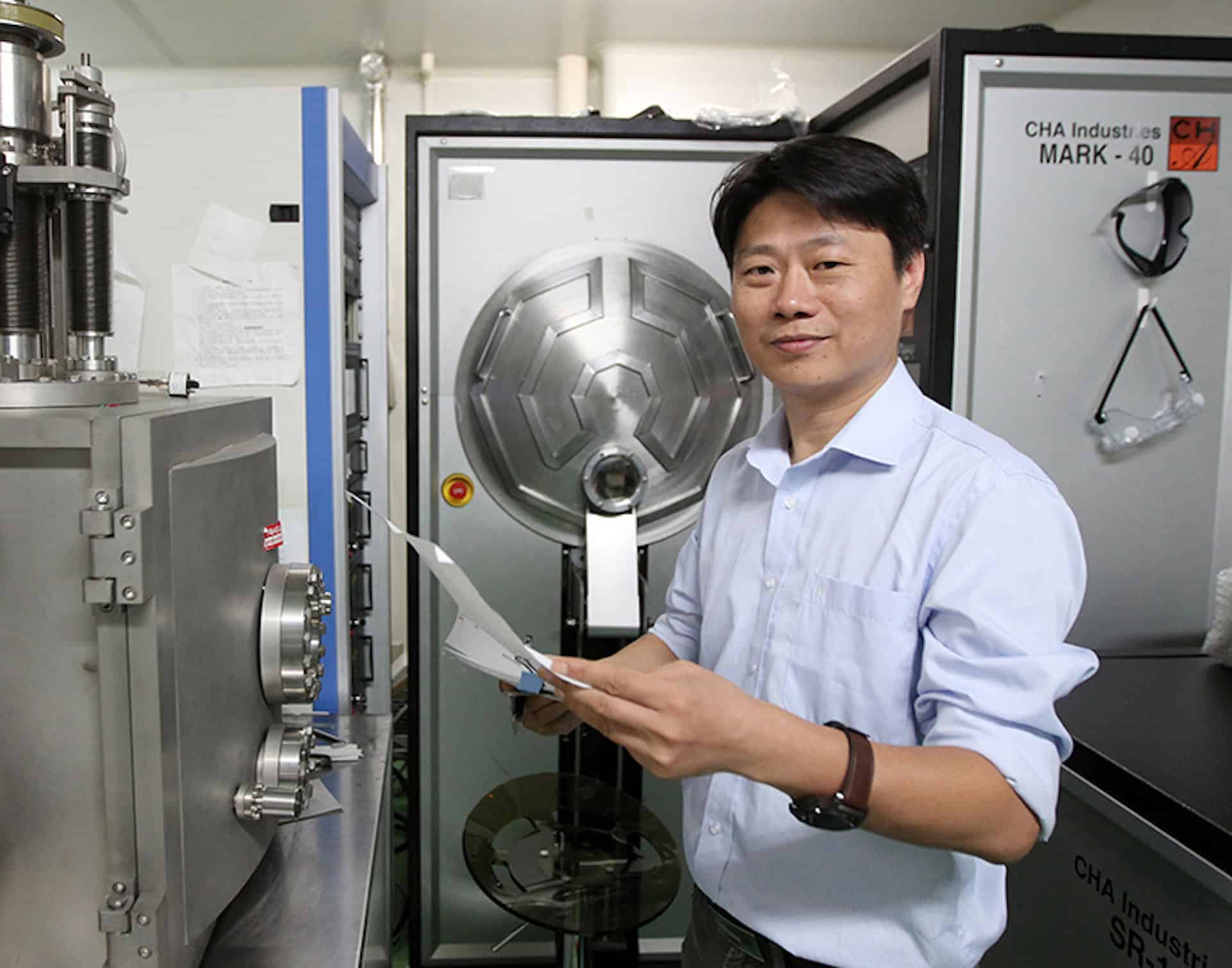

SpinQ, a Shenzhen-based quantum startup, has taken the opposite tack from Origin Quantum.

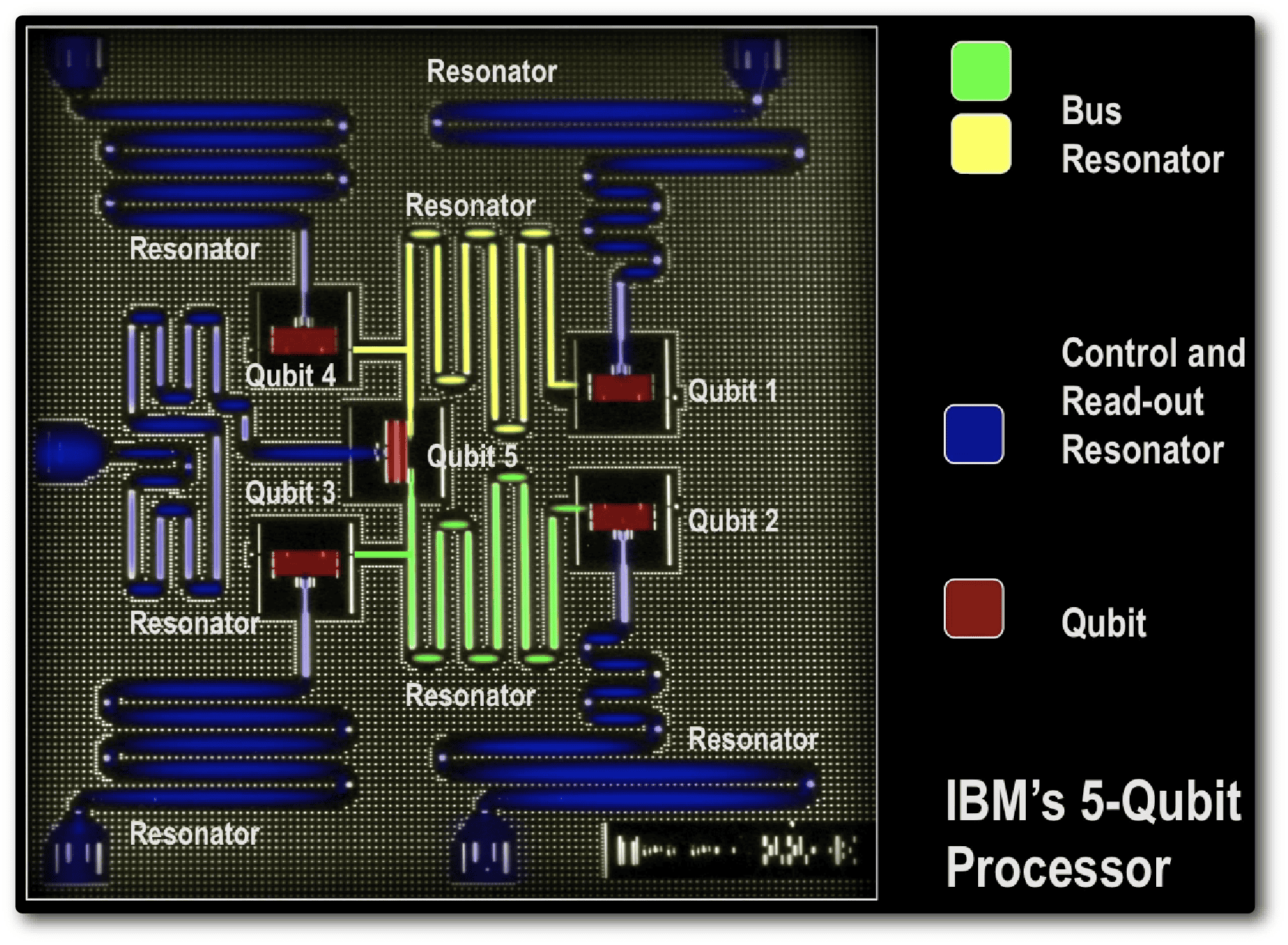

“We know from our own experience the value of internationalization,” says co-founder Xiang Jingen, who was a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University and spent years working in Canada. Xiang says he was inspired to start his own quantum company after IBM shared its 5-qubit quantum processor with the world by putting it on the cloud in 2016. “Our team believes exchange is important, and you cannot build a quantum computer behind closed doors.”

To date, SpinQ has sold more of its Gemini Mini — a 2-qubit portable quantum computer about as big as a toaster — to universities overseas than domestically. Besides technological advances, Xiang says global cooperation is necessary to bring down costs and figure out quantum industrialization.

Left: A selection of SpinQ’s educational grade nuclear magnetic resonance quantum computing products, including the Gemini Mini. Right: SpinQ’s Superconducting Quantum Computer. Credit: SpinQ

Those hoping to scale beyond the scientific standpoint, however, are still in for a long slog. While some within the industry argue there could be practical applications as early as the end of this decade, Jensen Huang, chief executive of Nvidia, recently said quantum technologies were still 15 to 30 years away — an assessment that wiped billions off quantum computing stocks.

Given that volatility and time frame, some say Chinese quantum companies are in a better position since government support is often seen as more reliable in China. Origin Quantum, for instance, is backed by several government entities or state-owned companies, according to data from WireScreen, including the China Construction Bank Corporation and the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC).

But while state-affiliated funds align their investments with government priorities, they aren’t necessarily more patient. “State-funds have much less risk appetite, and it causes a lot of problems,” Huber says. “For instance, the terms would be very harsh for entrepreneurs, including having personal liability for some of these investments.”

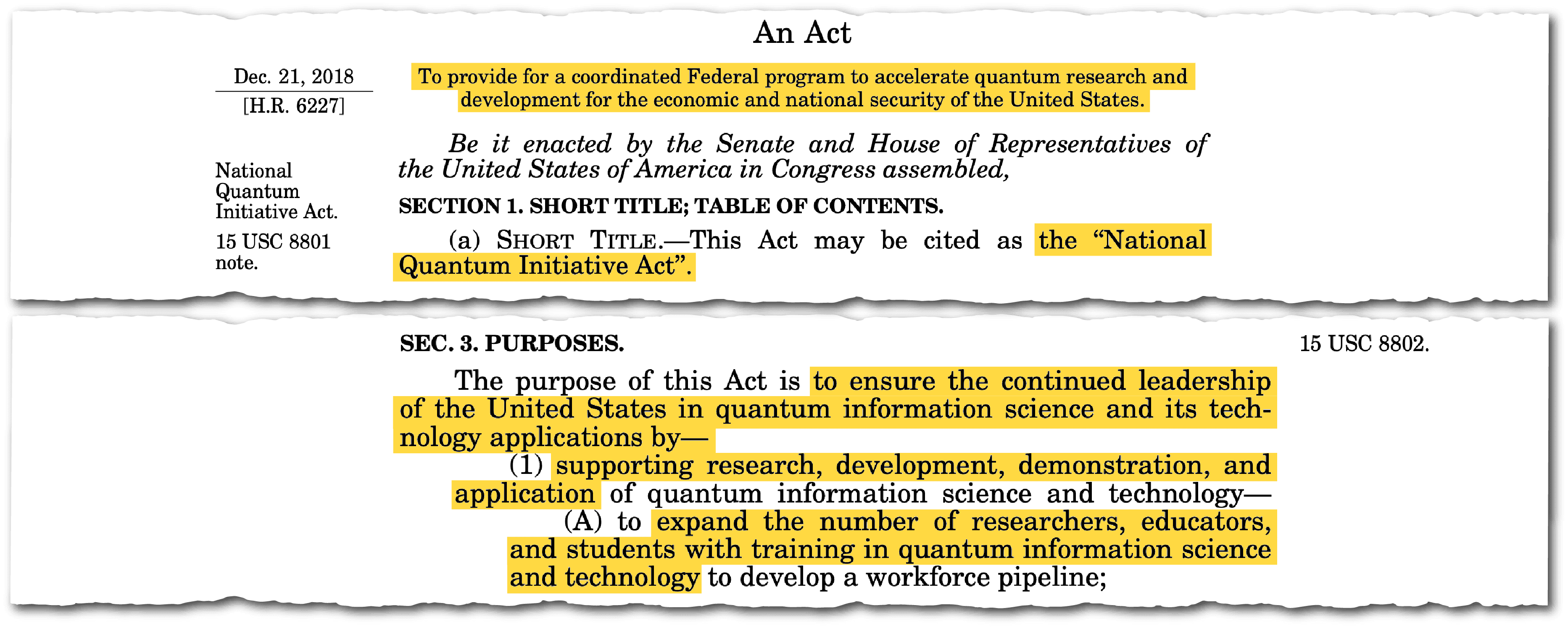

China’s top-down approach is also often heralded as an advantage in quantum, because it can be more coordinated and efficient. But in a report last year, the Chinese Academy of Science and Technology for Development and a Chinese quantum think tank pointed out that China still does not have a national framework like the U.S. does: In 2018, the U.S. passed the National Quantum Initiative Act, which coordinates between federal agencies and research institutes to ensure U.S.’s leadership in the field. The Chinese report identified the absence of something similar as China’s top challenge, saying such forward-looking plans are needed to “find a shortcut and overcome the U.S.’s technological blockade.”

Both the U.S. and China, then, cycle through periods of panic that they are falling behind. While there is certainly a competition happening, Kania characterizes the rivalry in quantum technology, and especially computing, as not just a marathon but “multiple marathons, all on different routes, and no one knows which will be faster or which will get there first, or even how long the course is.”

In other words, both sides need to remember to pace themselves.

Rachel Cheung is a staff writer for The Wire China based in Hong Kong. She previously worked at VICE World News and South China Morning Post, where she won a SOPA Award for Excellence in Arts and Culture Reporting. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Columbia Journalism Review and The Atlantic, among other outlets.