It is a paradox that Xi Jinping remains an enigma, given that for the past 12 years he has been leader of the world’s largest military, second-largest nation by population size, second-largest economy, and second-largest political party.

Xi Jinping stands with the members of the Politburo Standing Committee and addresses goals set by the National Congress, October 27, 2022. Credit: CCTV

Xi’s interactions with foreign leaders and other outsiders are highly scripted, leaving next to no space for spontaneous interactions. Little is known about his personal habits and interests. The circle he trusts for counsel is small and shrinking. In public appearances he is controlled, measured, enigmatic. China’s — and Xi’s — isolation during its draconian Covid lockdowns only exacerbated this trend toward impenetrability.

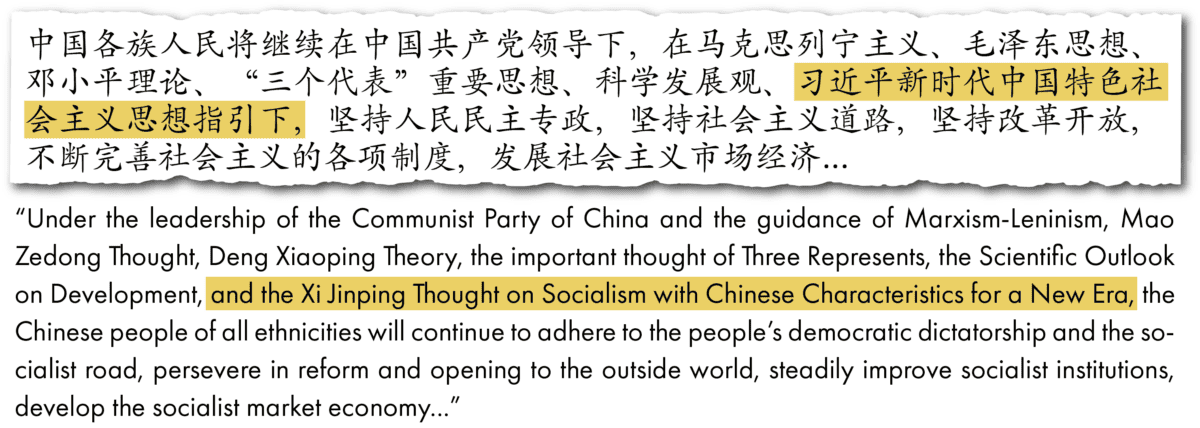

But if we don’t know much about Xi the man, the same cannot be said about what Xi thinks. Here, his output has been prodigious, assembled and presented to the world beginning in 2017 as “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” (习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想). It doesn’t matter that the hundreds of speeches and commentaries with his name as the sole byline are produced by a sophisticated machine of propagandists and advisors — each and every piece with his name attached carries his imprimatur. Xi wants China’s political machinery and the Chinese people to know exactly what he thinks, for theirs is the burden of translating his ideas about economic development, military power, the structure of society and foreign relations into action. He wants the world to know what he thinks, for he sees global politics as a battle not only of influence and power, but also of ideas and narratives. And it is in that realm that Xi sees an opening to shape international perceptions of China, not just as a superpower, but as a global solutions provider.

Xi wants the world to know what he thinks, for he sees global politics as a battle not only of influence and power, but also of ideas and narratives.

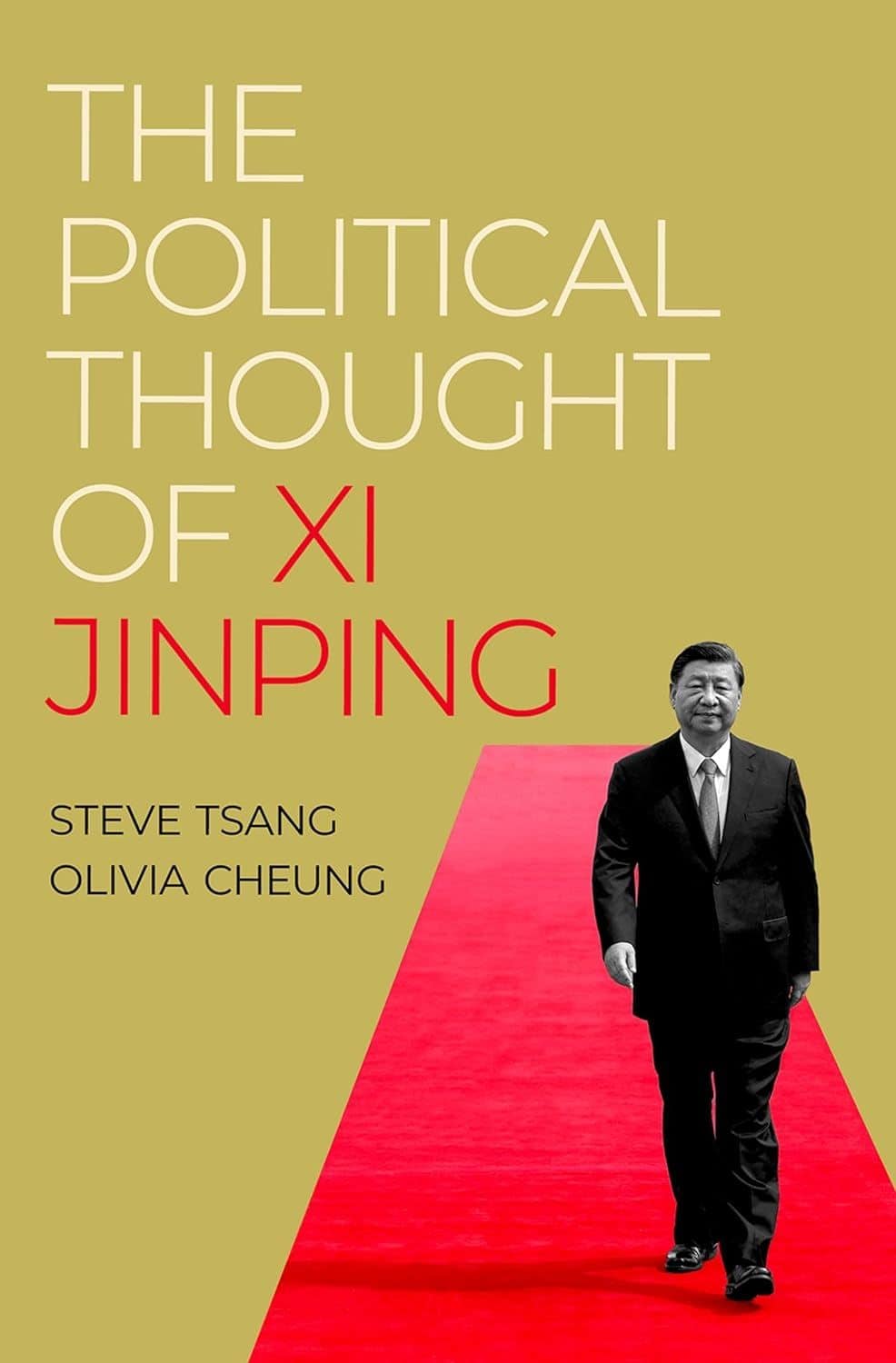

Synthesizing Xi Jinping’s voluminous thought is the subject of two recent books, both published by Oxford University Press. Steve Tsang and Olivia Cheung’s The Political Thought of Xi Jinping (January 2024) provides a balanced, brisk overview of Xi’s ideas about governance, politics and society. Ambassador Kevin Rudd’s On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism is Shaping China and the World (October 2024) is more ambitious, seeking a macro-thesis explaining Xi’s overall political-ideological project that centers Marxism — not just Leninism — in driving Xi’s agenda and worldview.

One of the first books to treat Xi’s ideas seriously (as opposed to the many other titles that explore his family story, his tenure as General Secretary, and his foreign and domestic policy), The Political Thought of Xi Jinping applied “three concentric circles” of sources to understand his underlying ideology: Xi’s oral and written remarks; the macro-policy plans that have been promulgated on his watch; and an analysis of how Xi’s vision has been implemented (or not).

Tsang and Cheung, both academics at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), succeed in their concise distillation of Xi’s major political and policy priorities, including both his aspirations and his paranoia. While the authors harbor clearly-articulated concerns about China’s grand strategy under Xi, the text is more analytical than alarmist. Clinical in their language, they steer the reader through a crisp 210 pages that build a foundational understanding of Xi’s expansive policy and political agenda since he came to power in late 2012.

According to Tsang and Cheung, “Xi Jinping Thought” is a body of evolving ideological and governance concepts that, unlike Mao Zedong Thought, is not wedded to Marxist principles of permanent revolution, but instead focuses on reinvigorating the Leninist tendrils that keep the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in power domestically, and channeling China’s formidable resources to establish China as a comprehensive global superpower. While the authors see Xi Thought as deeply ideological, it is an ideology tied not to communism, but to serving the CCP. They conclude that Xi Jinping Thought “is mostly, if not exclusively, about the security of the regime and its core leader, without a real commitment to delivering socialist ideals. The elements in Marxism-Leninism central to Xi Thought come not from Marxist teachings but from the Leninist principles of organization, control, and discipline.”

It is worth lingering on this assertion, for the question of where and how Marxism matters to Xi Jinping and the CCP he commands runs through both of these books.

For Tsang and Cheung, Xi’s relationship to Marxism is complicated. While Xi’s immediate predecessors — Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin — paid lip service to Marx, the authors see the current General Secretary as seeking to graft a “sinified” version of Marxism onto Leninism and nationalism. Like Mao, Xi wants to borrow from Marx, while ignoring the elements of Marxism that don’t fit with his governing philosophy. As Tsang and Cheung write:

“To Xi, the essence of the ideology is Marxism-Leninism as appropriated by himself based on his understanding of Chinese history for use in the era he is ushering in for China. In other words, while its doctrines are essentially Marxist-Leninist, their meanings are based on Xi’s interpretation, which is heavily ladened with party-centric nationalism.”

There is no doubt that, in an important sense, Xi draws deeply on the ideas of classical Marxism. Like prior CCP leaders, Xi sees not history, but History — a grand Hegelian sweep of events that moves, inexorably, towards Progress. George Kennan captured this belief in an unpublished essay from 1947 on the role of ideology in Soviet foreign policy:

“It is in the light of ideology, and in the language of ideology, that Soviet leaders become aware of what transpires in the world. They think of it, and can think of it, only in the terms of Marxist philosophy. Their own education knows no other terms … Ideology, we must remember, provides the jargon of official Soviet life. And in that sense, it pervades all understanding and discussion of objective reality.”

The eventual triumph of the stated goal of the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” (中华民族伟大复兴) is not a hypothesis for Xi; it is as inevitable as the dialectical march of historical materialism itself. For Xi, China’s rise is not just a political goal but a fulfillment of historical destiny, where the contradictions of global capitalism will be resolved in China’s favor, leading to the nation’s rightful place as a global leader in a new world order.

When Xi Jinping speaks of China entering a “New Era,” he draws not only from the legacy of periodization that has long defined traditional Chinese thought about the rise and fall of dynasties, but from the wellspring of Hegalian-Marxism and its vision of historical progress. The “New Era” signifies a decisive break from the past, where China, under the leadership of the Communist Party, will resolve the contradictions of development both domestically and internationally. This is not merely a narrative of economic growth or national strength; it is a comprehensive ideological mission to transform China, and the world around it. Xi sees himself as a key agent in this historical process, cementing the CCP’s legitimacy not just as a ruling party but as the ultimate custodian of China’s historical trajectory.

Like prior CCP leaders, Xi sees not history, but History — a grand Hegelian sweep of events that move, inexorably, towards Progress.

In On Xi Jinping, Kevin Rudd has written the most comprehensive analysis of Xi to date — one that will set the bar for future studies of Xi’s governing philosophy. Part of the richness of the book comes from Rudd’s unique vantage point, having served as Prime Minister of Australia from 2007–2010 and again in 2013, its foreign minister from 2010–12, and now its ambassador to the United States since 2023 (to say nothing of his time running Asia Society from 2021–231Disclosure: China Books Review is co-published by Asia Society’s Center on U.S.–China Relations, and as a full-time student of Xi Jinping Thought while undertaking his DPhil at Oxford, which he received in 2022). Rudd is also likely the only author of a study on Xi to have spent time alone with his subject, as he did when Xi visited Canberra in 2010, when Rudd was serving as Prime Minister.

This singular work, which emerged from Rudd’s doctoral thesis at Oxford, brings with it a tactile ability to view Xi through multiple lenses: politician, bureaucrat, coalition-builder, grand strategist. The book draws from an extraordinary range of primary sources in Chinese, secondary sources and academic literature (the footnotes and bibliography alone are over 170 pages) to build a comprehensive composite of Xi’s worldview, the sources that inspire it, and how he is channeling that to transform China. There is very little by way of personal biography, unlike other titles on Xi — it is rather a study in ideas, ideology and governing philosophy.

Rudd argues that Xi is profoundly different from his immediate predecessors (Hu Jintao, Jiang Zemin, Deng Xiaoping) in three important respects. First, Xi has moved domestic politics towards what Rudd calls the “Leninist left,” which entails a dramatic centralization of decision-making, a disciplinary rectification of the Party, and a reinvigoration of orthodox ideology throughout the policymaking and governance apparatus. Second, economic policy under Xi has shifted to the “Marxist left,” with a de-emphasis on the growth-at-all-costs model that defined much of the Reform and Opening era, a higher tolerance for state intervention in the economy, and a shift in spending priorities toward technologies that will power the Chinese economy in decades to come. Third, foreign policy under Xi has become more confrontational and assertive, in a move toward the “nationalist right” that strives to center Chinese power in its regional relationships, to alter global institutions to better serve Chinese interests, and to create advantageous terms in its bilateral relationship with the United States.

Taken in whole, Rudd sees China’s transformations as coalescing into a new ideological-governance framework that he calls “Marxist-Leninist nationalism,” or “Marxist nationalism” for short. In his words, this “encompasses a clear-cut, historically determinist mission for a new era, an all-powerful Leninist party and paramount leader to oversee this mission, and a commitment to relentless struggle to overcome the emerging contradictions identified both at home and abroad through the tools of dialectical materialism.”

In contrast to Tsang and Chueng, Rudd does not view Xi’s national project as primarily focused on ensuring the Party’s grip on power, although he argues that this certainly matters to Xi. Nor does he see Xi’s adherence to Marxism as shallow or ideological theater. Xi, Rudd argues, is a real, bone fide Marxist, not just in his adoption of its analytical techniques, but also in how he sees the substance and direction of policy and governance more broadly. “Xi’s Marxist-Leninist Nationalism,” he argues, is “not just cynically seen as a convenient intellectual fiction to hold the party together and to define its enemies both within and without.” Instead, he sees a “fundamental commitment to Marxism-Leninism,” with dialectical materialism being the “intellectual engine room” of Xi’s Marxist worldview.

Rudd argues that Xi’s ideological convictions are genuine and foundational, driving his efforts to assert Party control, reshape the international order, and secure China’s future as a socialist superpower. This is perhaps the most substantial disagreement between these two works: Tsang and Chueng see Xi’s Marxism as a patina, whereas Rudd believes that Marx’s ideas — alongside those of Lenin and key aspects of Chinese history and culture — form the core of his worldview.

Rudd sees China’s transformations as coalescing into a new ideological-governance framework that he calls … “Marxist nationalism.”

Marxist theory centers on the idea that history is driven by class struggle rooted in material conditions. Karl Marx argued that societies evolve through stages, from feudalism to capitalism, each defined by the dominant economic system and class relations. In capitalism, the bourgeoisie owns the means of production, while the proletariat sells its labor for wages. This relationship is exploitative, as capitalists profit by extracting surplus value from workers. Marx believed this exploitation would lead to the creation of a revolutionary class consciousness, driving the proletariat to overthrow capitalist systems. He predicted socialism would emerge in its place, with collective ownership of the means of production, eventually leading to a stateless, classless society (communism) where wealth is distributed based on need, not profit.

Can such a theory be plausibly overlain on the actual, existing political system in contemporary China, even under an ideologue such as Xi? Can one make a tenable case that Xi is attempting to steer the Party-state apparatus toward Marx’s utopian vision, or even toward a more pragmatic version of socialism?

It is true that Xi has frequently extolled Marx, calling him “the greatest thinker of modern times” and declaring that “the belief in Marxism and the faith in socialism and communism are the political soul of the Communists and the spiritual pillar that enables the Communists to withstand any test.” He has exhorted the CCP to realize communism, and invoked dialectical and historical materialism in countless speeches and articles as vital tools of statecraft and ideological orientation. It’s also undoubtedly true, as Rudd demonstrates, that Xi and the Party apparatus lean heavily on a Marxist lens to interpret the world, to understand the gyrations of History, and to explain the structural contradictions between socialist China and the capitalist West. Indeed, one cannot understand Xi, or China’s sui generis political architecture, without understanding the functional power of Marxist frameworks in shaping the Party’s worldview. Just as the once-open Russian and Chinese archives demonstrated that Soviet and Chinese leaders during the Cold War made key decisions based on ideology (in addition to realpolitik), so too will future historians discover the extent to which Xi’s ideological worldview drives his decision-making.

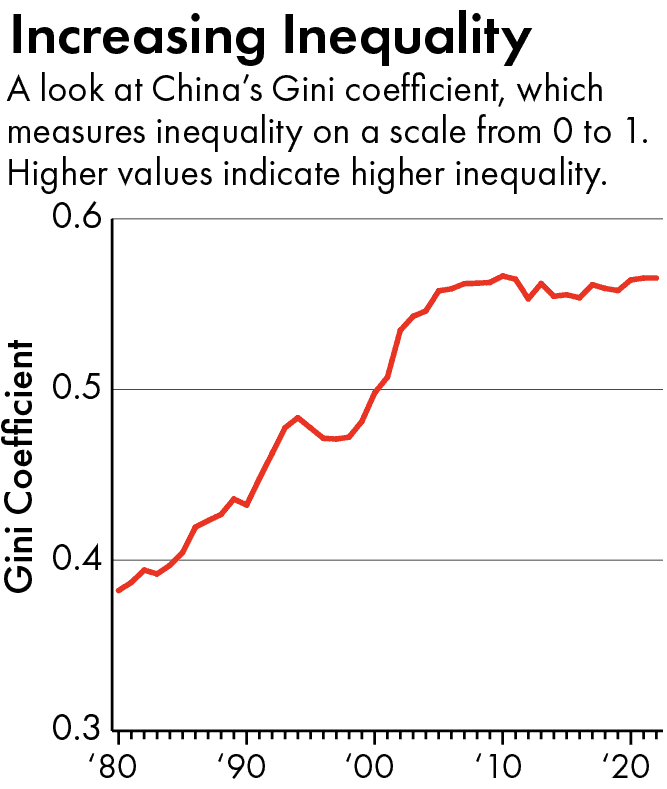

Yet Xi’s brand of Marxism is, to be charitable, conflicted. There is no doubt that Xi is hostile to free-market capitalism, and sees what he calls its “final demise” as the precondition for socialism’s “final victory.” Xi has also revamped and redefined China’s economic development model away from growth-at-all-costs to one that, purportedly, will pursue a better quality of economic activity, including more equitable income redistribution, environmental stewardship, and the redistribution of capital towards the “real economy” (away from the financiers and real estate speculation and towards manufacturing and a genuine housing market). Xi’s campaign to end absolute poverty through a “targeted poverty alleviation” policy inaugurated in 2013, for all its shortcomings, led to a meaningful decrease in poverty incidence in both rural and urban areas. And his administration also continues to push forward on hukou (rural registration) reform, which remains a critical barrier to social improvement for vast numbers of migrant laborers.

Can Marxist theory be plausibly overlain on the actual, existing political system in contemporary China, even under an ideologue such as Xi?

This, however, is Marxism at the far margins. What would Marx make of contemporary China under Xi? It is difficult to speculate, but there is much he would likely not approve of. Xi’s government routinely jails labor activists and student Marxists, cracking down on the very groups Marxists would champion. When his “common prosperity” initiative, which sought to reduce income inequality and ensure more equitable distribution of wealth, seemed in danger of encouraging calls for a full-blown European-style welfare state, Xi used the Party’s authoritative Qiushi journal to declare in October 2021 that China “should resolutely prevent falling into the trap of ‘welfareism’ to support lazy people.” This sounds more like Milton Friedman than Karl Marx. More than three years since “common prosperity” got its initial push, it has faded to the margins of policy discussion.

Although wealth distribution in China has long been highly unequal, citizens tolerated these disparities because they believed that their personal efforts could lift them from poverty to relative prosperity. Yet a recent Stanford University research paper shows that for the first time in 20 years, most Chinese respondents believe wealth is shaped by structural inequalities rather than individual merit. There has been no widespread tax reform, which is essential if China is going to adequately provide for the medical and social services needed to support the coming wave of retirees exiting the workforce. Despite some recent progress, educational opportunities and outcomes vary widely by income and geography. China’s healthcare system remains underfunded and ruthlessly capitalist.

Indeed, after more than a decade in power, Xi has failed to implement any significant policies that have fundamentally and genuinely moved China closer to a type of socialism that makes breakthroughs in enriching the people, not just the state. By way of comparison, areas that Xi Jinping clearly sees as priorities, such as national security, have witnessed a wholesale transformation as Xi applies his significant political capital to drive reform in the face of stiff opposition. A real Marxist would take the resources and energy that have been plowed into Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, his military modernization and his “overall national security outlook,” and instead channel them into fiscal, educational and health care reform.

Any plausible argument for prioritizing socialism evaporates when the field of analysis is Xinjiang or Tibet. For decades, the CCP has waged campaigns of repression and social transformation in Xinjiang and Tibet, aiming to tightly assimilate these regions into the full ideological and governance sphere of the Chinese Party-state. In Xinjiang, mass surveillance, forced internment of Uyghurs and restrictions on religious practices have been central to Beijing’s effort to suppress ethnic identity and dissent under the guise of counterterrorism. Similarly, in Tibet the CCP has sought to erode the region’s unique culture and religion through restrictions on Buddhist practices, heavy-handed political control and mass migration of Han Chinese settlers. Both regions have seen intensified efforts at sinicization, with Beijing seeking to reshape ethnic, cultural and religious identities in line with state ideology.

Of course, repression alone doesn’t negate the theory of Xi’s Marxism. Indeed, one of the oldest, most contested debates of the Cold War period was this: Did Marx invent the Gulag? In other words, was Stalinism and Maoism — and all the slaughter that accompanied actual, existing communism in the 20th century — the inevitable outcome of Marx’s ideas? If so, Xi is simply the direct and ineluctable offspring of Das Kapital. It is a valid question, and one where persuasive arguments have been put forward on both sides of the proposition. But it is important to recognize that labeling Xi Jinping as a “Marxist” should come with deep qualifications, as his governance agenda shows little commitment to the kind of radical economic and social transformation that Marx originally envisioned.

A segment from a speech delivered by Xi Jinping at a conference marking the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth, May 4, 2018. Credit: CGTN

When it comes to Xi’s pronouncements on Marx and Marxism, we might appropriate Leszek Kolakowski’s appraisement of Mao’s philosophical writings in his monumental 1976 book Main Currents of Marxism: “To put it mildly, much good will is needed to perceive any deep theoretical significance to these texts.” Xi’s speeches and writings on Marx and socialism mirror the superficiality of his grasp of — or genuine interest in — deep Marxism. Like the fear-driven attention lauded on Stalin’s 1938 course text History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Xi’s orations on Marxism are politely applauded and his disquisitions in Qiushi magazine are carefully scrutinized in Party study sessions. But no cadre gets smarter about Marxism after reading or listening to them. Consider his speech marking the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth, a moment when acumen as a Marxist interpreter should be most evident. Instead we get this empty pablum:

“A history of the development of Marxism is the history of Marx, Engels and their successors who have constantly developed according to the times, practice and the development of understanding, and the history of constantly absorbing all the excellent ideological and cultural achievements in the history of mankind to enrich themselves. Therefore, Marxism has been able to maintain its wonderful youth, constantly exploring new issues raised by the development of the times and responding to the new challenges facing human society.”

One can wade through Xi’s pronouncements on Marx in the hopes of enlightenment, but will search in vain for any original theoretical advancements — or indeed any sense that Xi believes in the fundamental Marxist project of the emancipation of the proletariat.

Xi also understands that Marxist ideas, if allowed to spread unchecked in China, could well become a potent weapon for criticizing the Party. The left flank of the ideological spectrum — as I explore in China’s New Red Guards: The Return of Radicalism and the Rebirth of Mao Zedong (2022) — has always been the most exposed for the CCP, as it is only from the left that the purported “socialist” orientation of the Party can truly be challenged on its face. To prevent this, Xi has deftly contained the discourse, ensuring that Marxist principles are sanitized and deployed selectively, under strict Party control, to reinforce loyalty and suppress dissent. By co-opting revolutionary rhetoric, Xi hopes to avoid Marxism being used to highlight contradictions in the Party’s governance or economic policies, which, for nearly 50 years, have diverged from socialist ideals. In this way, Xi’s Marxism becomes a tool of statecraft, not a weapon of proletariat liberation.

Rather, with Xi there is overlap with a critique of Stalinism that grew in the period around and after the Stalinist purges of the 1930s — what Trotsky called, in a 1937 essay, “the revolution betrayed.” Just as Trotsky condemned state capitalism under Stalin for “supporting unviable enterprises” and “perpetuating parasitic social strata,” Xi calls for the nation’s gargantuan state-owned enterprises to become “stronger, better and larger” in their service of national greatness and the enrichment of the state, not the people’s livelihoods. Likewise, the entrenchment of an ever more powerful Party bureaucracy and organization under Xi has created what Trotsky condemned as the “sole privileged and commanding stratum.” In Xi’s cult of personality we see, as Trotsky did under Stalin, an “increasingly insistent deification” which “with all its elements of caricature, [becomes] a necessary element of the regime.”

Chinese propaganda posters from 2013 (left) and 2015 (right) featuring Xi Jinping, based on the theme of ‘The Chinese Dream’. Credit: BG E37/724, BG E37/932 (chineseposters.net, Landsberger Collection)

Of course there is no Trotsky in today’s China — at least not one willing to publicly level the charge of betraying the revolution. There is dissent and private grumbling, but the security and surveillance tools at Beijing’s disposal are too fearsome to ignore, and the consequences of open opposition are too high. Xi’s version of Stalinism will likely lurch along until he voluntarily steps down (highly implausible), is unseated (unlikely) or, more probably, dies on the throne.

Like Mao, Xi has selectively appropriated the superficial language of Marxism to justify his policies and consolidate his power.

If Xi Jinping Thought is not a vision for a genuine socialist movement driving towards a communist utopia, what is it? Here, both On Xi Jinping and The Political Thought of Xi Jinping are compelling in their description of Xi’s adherence to Lenin. In its purest form, Leninism advocates a highly disciplined, centralized political party to lead the working class in overthrowing a capitalist system. He argued that spontaneous revolution from the masses alone would be insufficient — a small, ideologically committed elite must guide the revolution to prevent it from being co-opted or crushed by reactionary forces. Once in power, this Party must suppress counter-revolutionary elements and begin building socialism by nationalizing industry, redistributing land and establishing state control over the economy. All of this can only be made possible by the implacable discipline of the Party apparatus. If Lenin had a foundational maxim, it was articulated in this 1920 essay:

“The Bolsheviks could not have retained power for two and a half months, let alone two and a half years, without the most rigorous and truly iron discipline in our Party.”

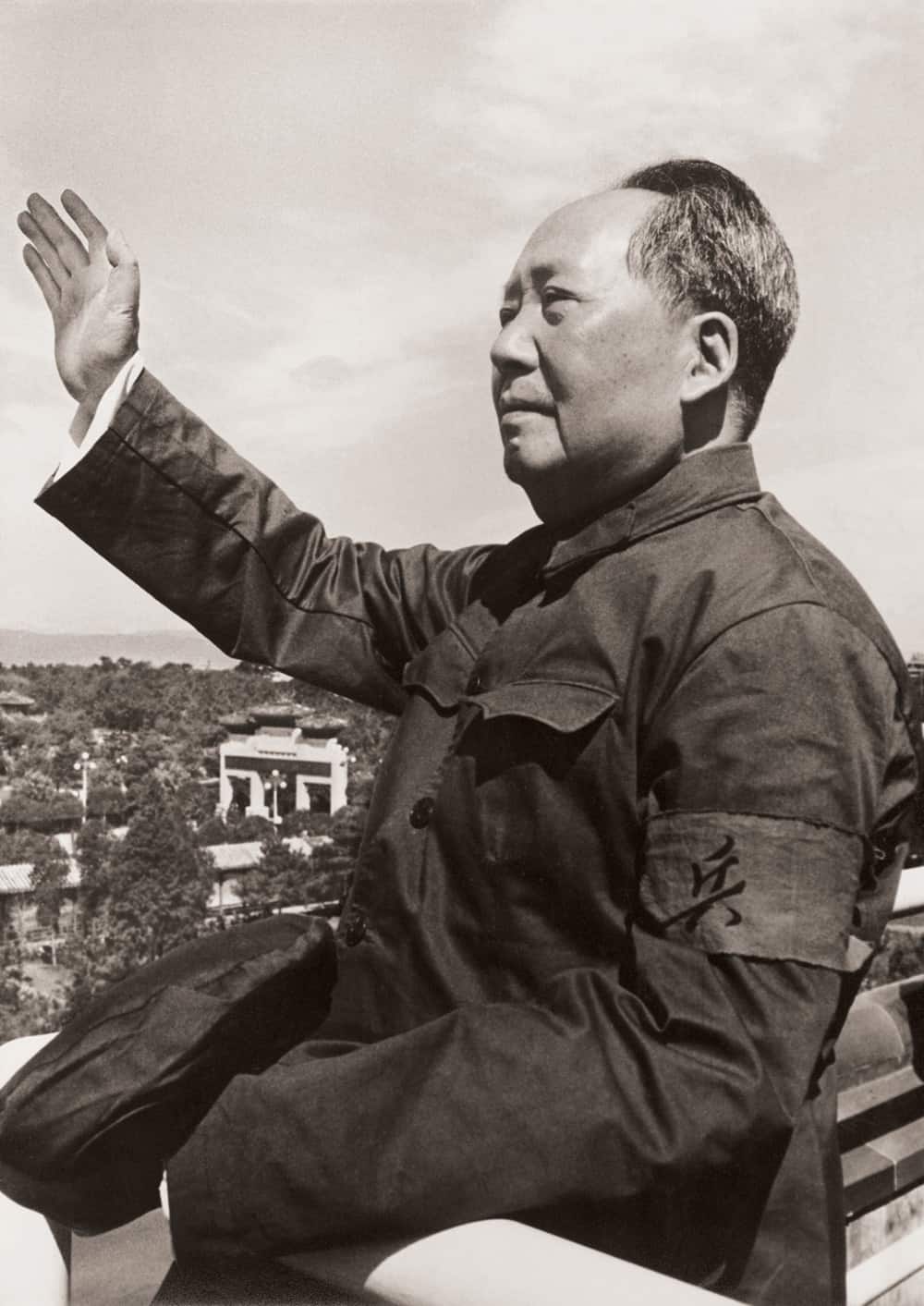

Mao Zedong had his own Leninist inclinations, but his path diverged sharply from Lenin’s, and thus from Xi’s. While Mao initially embraced the idea of a disciplined vanguard party, his relationship with the Communist Party eventually fractured in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In response, Mao turned against the very Party he helped create, launching the Cultural Revolution and igniting chaos within the ranks. He sought to purge the Party of perceived revisionists and counter-revolutionaries, believing that only through constant struggle and mass mobilization could the revolution stay alive. Mao saw revolution not as a one-time event but as a continuous, violent upheaval, often bypassing the Party apparatus and appealing directly to the masses.

Xi, on the other hand, has taken the opposite approach. His strategy centers on reinforcing the Party’s iron discipline and ensuring his absolute control over it. Rather than turning to the masses to challenge the Party’s authority, Xi has worked to instill loyalty within the Party itself, purging those he views as disloyal or corrupt but always under the banner of strengthening Party unity and organizational power. For Xi, the Party is not something to be questioned or overturned — it is the essential vehicle for maintaining stability and achieving national rejuvenation. While Mao ultimately went to war with his own Party, Xi has doubled down on Lenin’s vision of a tightly controlled, elite-driven organization, seeing it as the cornerstone of his political vision and the key to his long-term survival.

Xi understands that Leninism provides a potent ideological framework for autocrats, due to its inherent emphasis on centralized control, the suppression of political opposition, and the elevation of the Party as the sole legitimate representative of the people and their collective will. Built on a principle of concentrated leadership, justified by the need to prevent counter-revolutionary forces from undermining the socialist project, Lenin created a structural pathway for dictatorial power. One can easily see the path from Leninism to Stalinism to Maoism to Xi-ism.

But this is not Leninism for Leninism’s sake. Nor is it a continuous revolution to bring Marx’s vision of communism to China, or to realize heaven on earth. The true substance of Xi Jinping Thought is how to direct Leninism at a policy agenda focused on building and wielding comprehensive national power. While Chinese leaders and intellectuals since the late 19th century have sought to restore China’s central place in the international order, from Zeng Guofan and the Self-Strengthening Movement to Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, Xi is employing a new toolkit. He leverages cutting-edge technology, state-controlled capitalism and assertive foreign policy, with an unprecedented focus on expanding China’s influence across key global arenas. Unlike his predecessors, who often adopted more cautious or internally-focused approaches, Xi has mobilized far greater resources and directed the full machinery of the Party toward strategic ambitions on the world stage. His methods — which blend Leninist control with modern economic, technological and military prowess — represent a more aggressive and concentrated effort to reclaim China’s historical stature, with the long-term goal of challenging the current global power balance.

That is the goal. Yet it is becoming more evident by the day that to achieve this objective, Xi is corrupting the machinery of effective governance, like Stalin and Mao did before him. He has replaced pragmatism with paranoia, merit with loyalty, and debate with blind obedience. Governing institutions, that once seemed to be serving the nation as a whole, now serve one man’s unrelenting pursuit of power for the Party that he leads. Bureaucratic professionalism is giving way to fear-driven stagnation, as officials scramble to stay in favor, not to solve governance challenges. The promise of a prosperous, harmonious society has been bartered for the promise of stability, security and “national greatness.” Yet the price of pursuing these goals — paid in the currency of repression — continues to rise. The question is not just whether Xi will achieve his aims, but what will be left of China if he does.

This review was co-published with China Books Review.

Join China Books Review at Asia Society in New York tomorrow (October 18, 2024) for the book launch of On Xi Jinping, with Kevin Rudd in conversation with Li Yuan and Orville Schell (members only).

Jude Blanchette holds the Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. He lived and worked in China for more than a decade, most recently in The Conference Board’s China Center in Beijing. Blanchette has written for Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, The Wall Street Journal and others, and is author of China’s New Red Guards: The Return of Radicalism and the Rebirth of Mao Zedong (Oxford University Press, 2019).