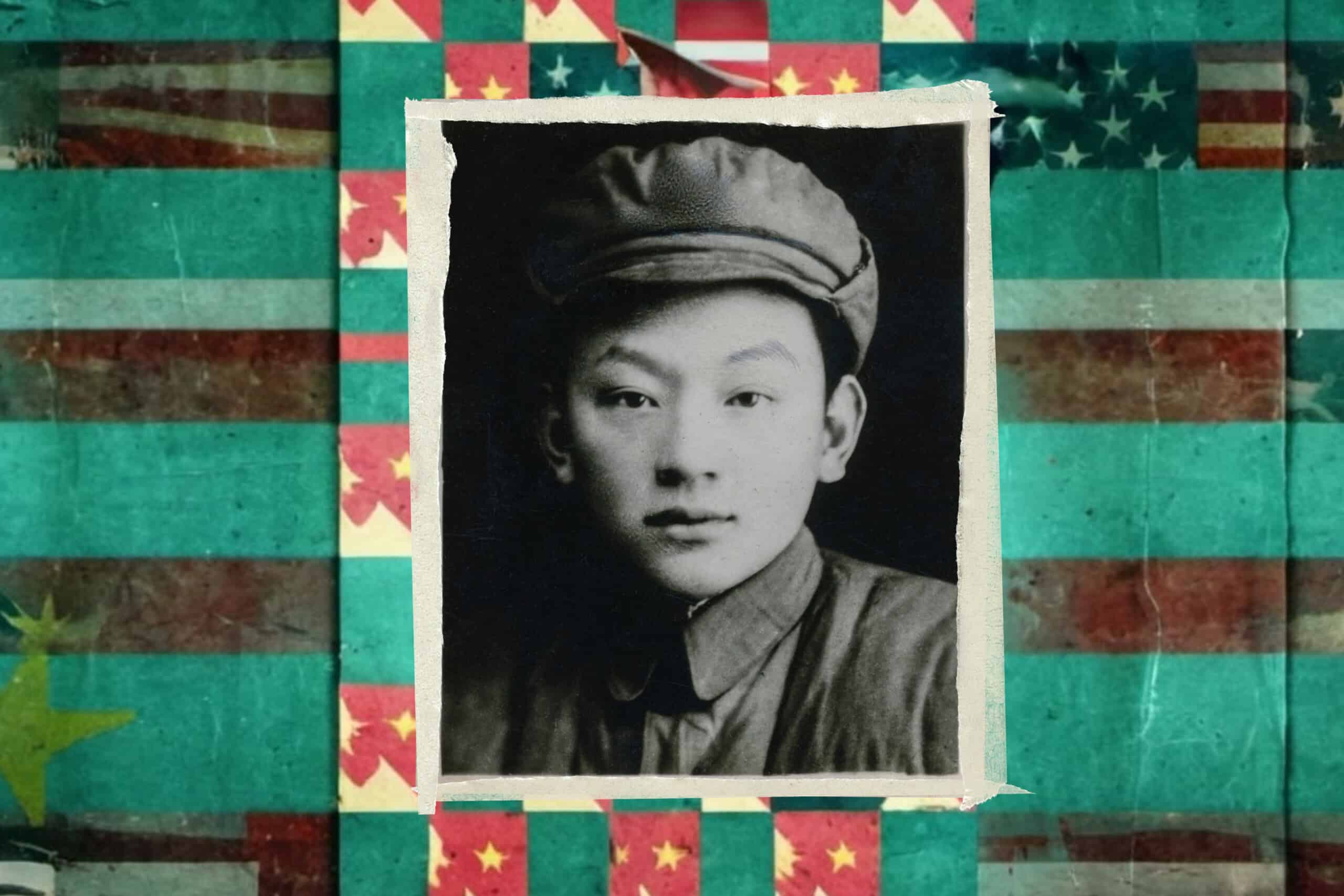

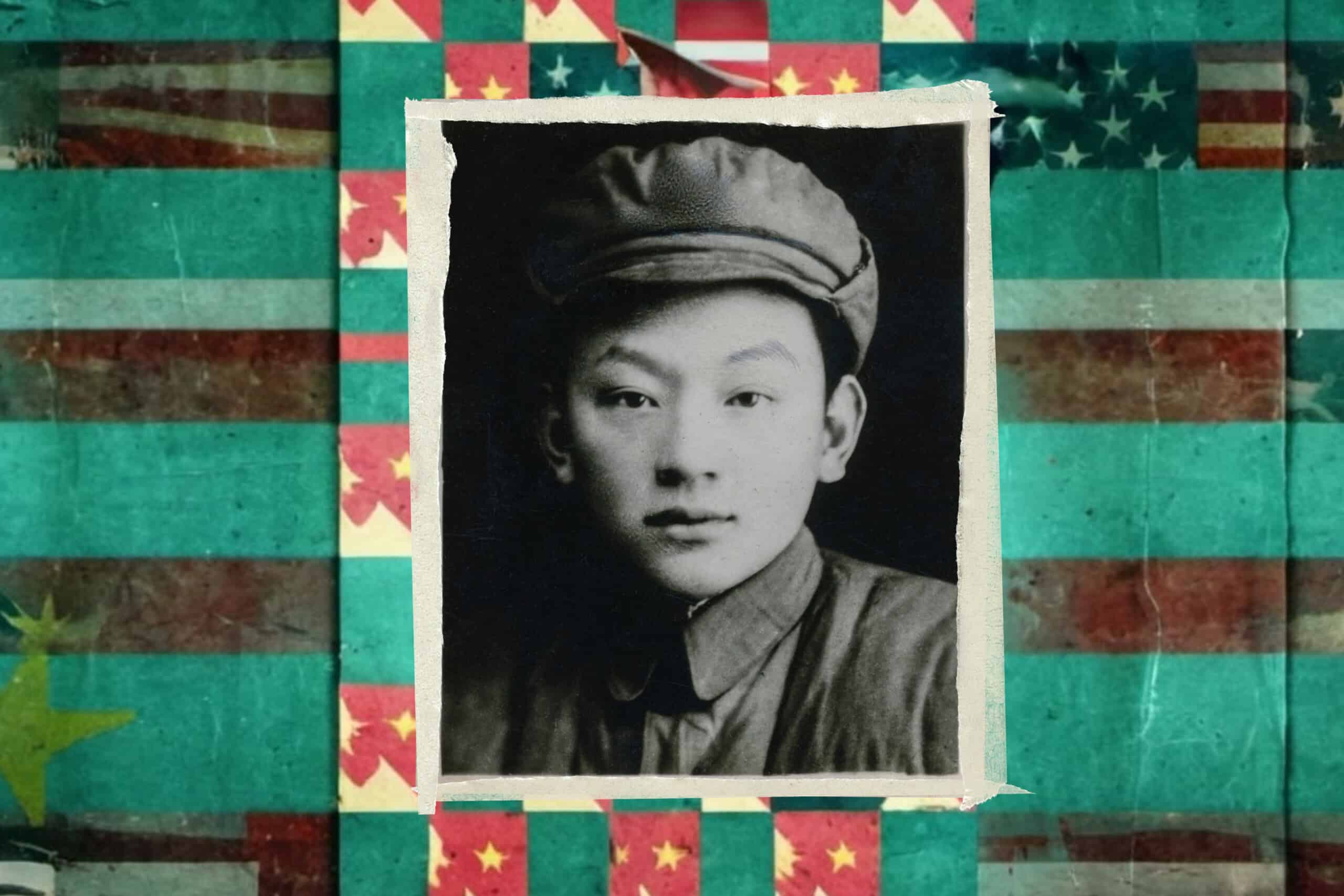

He remembered the persimmons hanging low from the trees in the autumn light. They dangled from the branches above his head, plump and smooth and the color of burnt copper. He sat in the open back of the truck alongside the other soldiers. Trees lined the road, and the air was crisp and dry. They pointed at the persimmons, marveled at them. How sweet it would be to bite into one. Dust trailed the truck as it continued down the dirt road. They were heading into a vast and sere land, a place of anc

Subscribe or login to read the rest.

Subscribers get full access to:

- Exclusive longform investigative journalism, Q&As, news and analysis, and data on Chinese business elites and corporations. We publish China scoops you won't find anywhere else.

- A weekly curated reading list on China from Andrew Peaple.

- A daily roundup of China finance, business and economics headlines.

We offer discounts for groups, institutions and students. Go to our

Subscriptions page for details.

Includes images from Depositphotos.com