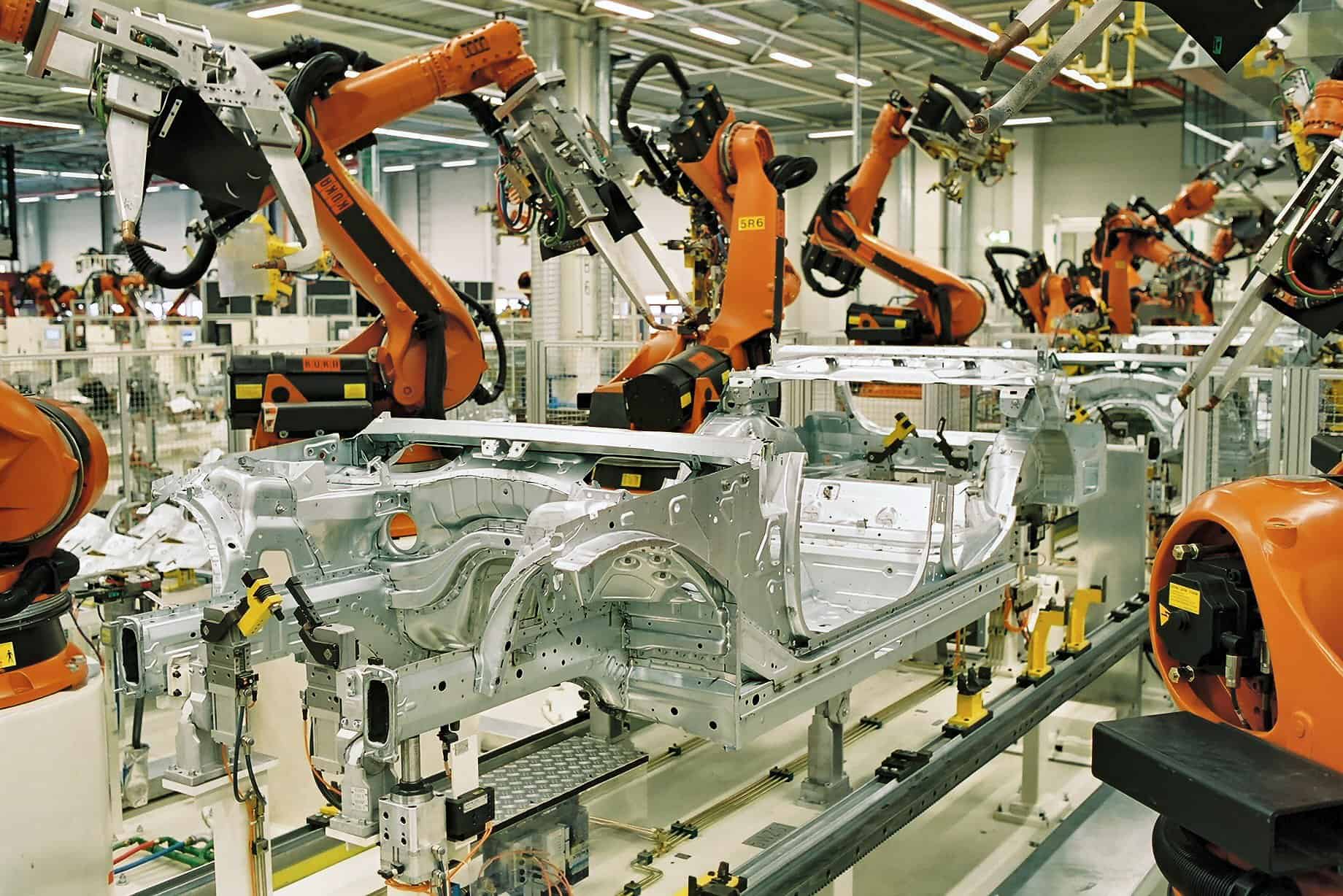

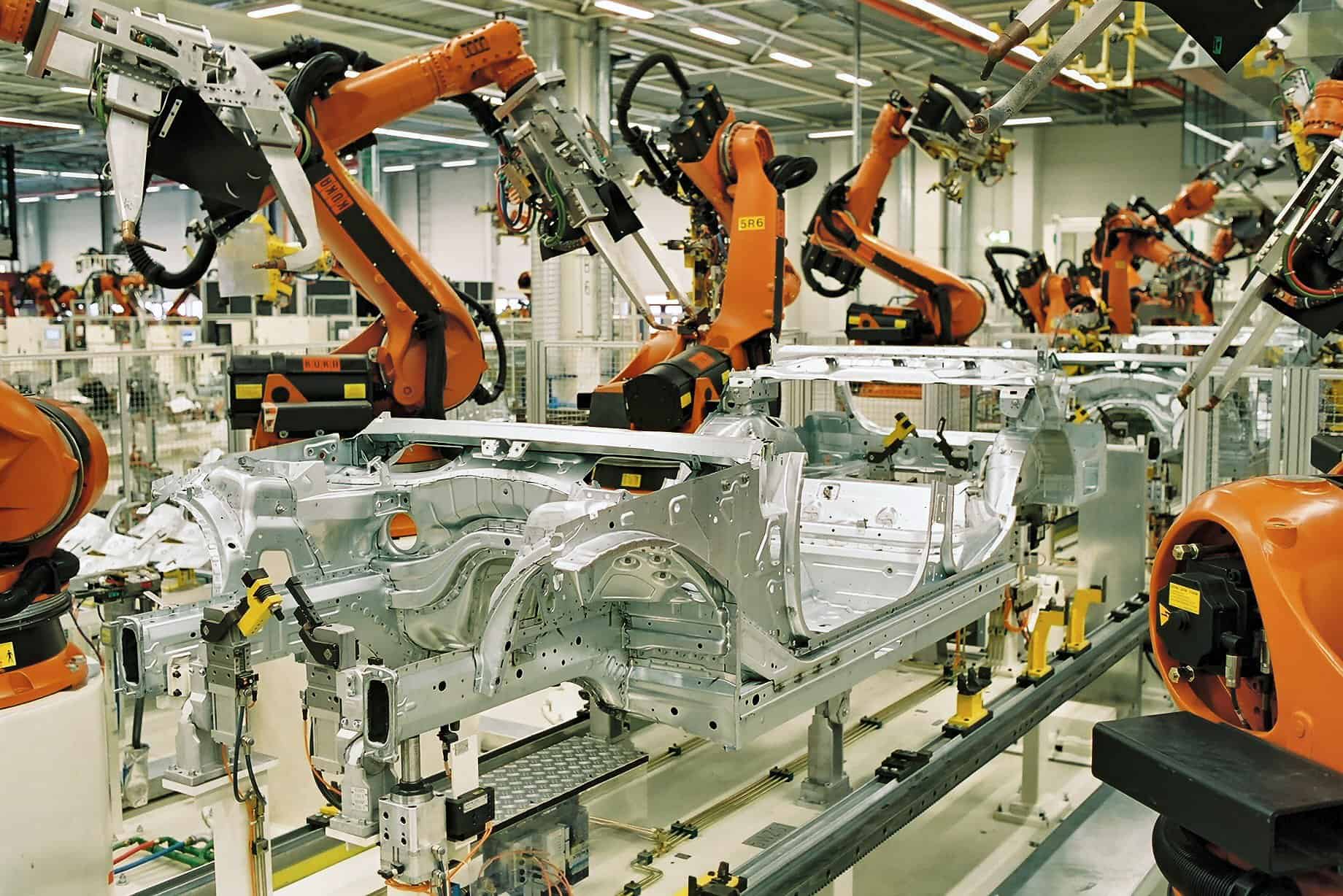

The march of the robots stalled globally last year — except, that is, in China.

Sales of industrial robots in the world’s second-largest economy jumped 19 percent in 2020, according to recent data from the International Federation of Robotics, compared with a slight 2 percent decline in overall global sales. The sharp rise has consolidated China’s position as a global leader in automation: even in 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, the country installed more robots than the next fo

Subscribe or login to read the rest.

Subscribers get full access to:

- Exclusive longform investigative journalism, Q&As, news and analysis, and data on Chinese business elites and corporations. We publish China scoops you won't find anywhere else.

- A weekly curated reading list on China from Andrew Peaple.

- A daily roundup of China finance, business and economics headlines.

We offer discounts for groups, institutions and students. Go to our

Subscriptions page for details.

Includes images from Depositphotos.com