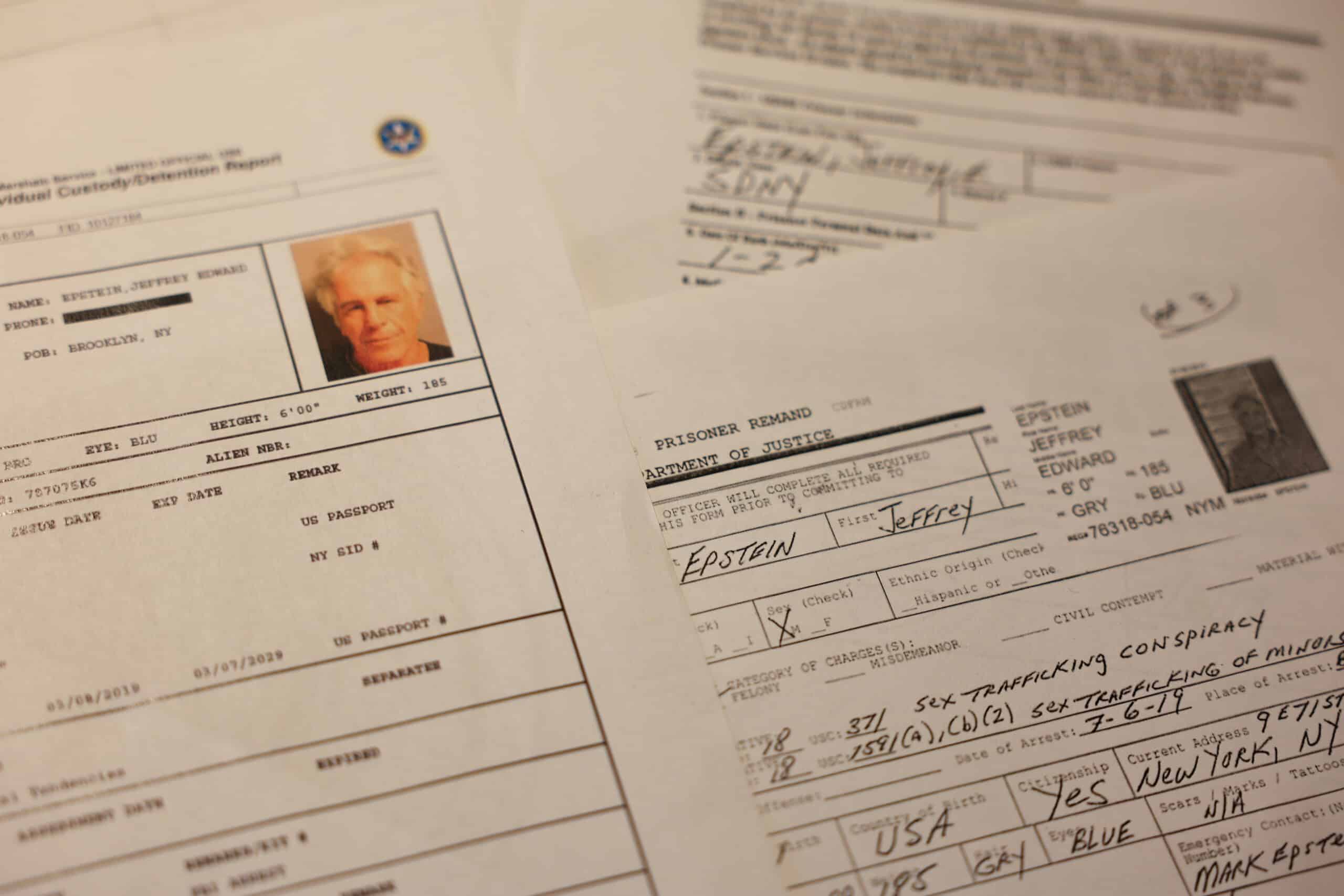

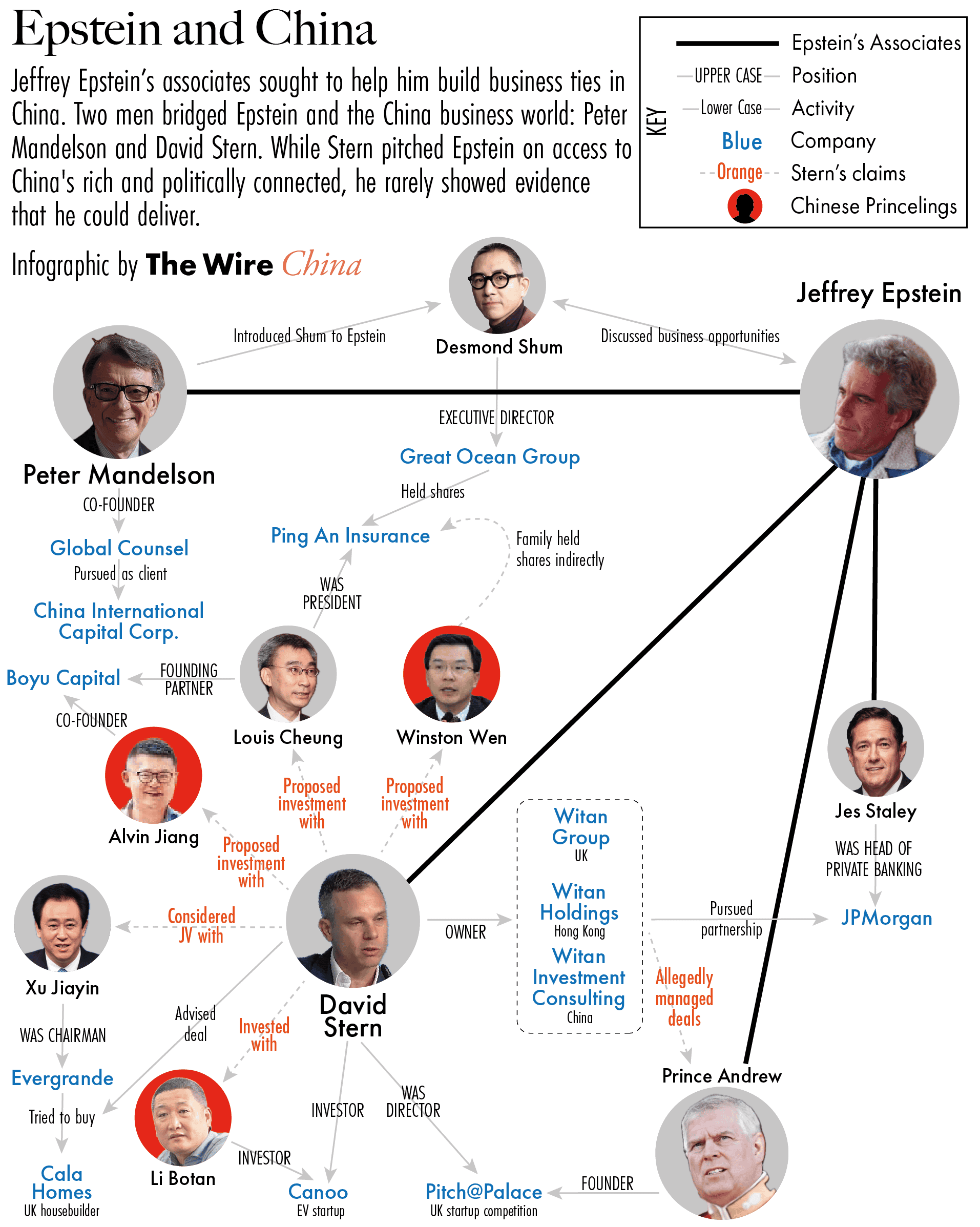

Documents recently released by the U.S. Department of Justice reveal how associates of Jeffrey Epstein sought to help him and his business partners build ties in China.

Bridging Epstein and the Chinese business world were Peter Mandelson, the veteran UK Labour Party politician, and David Stern, a businessman with close ties to Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, formerly Prince Andrew.

It isn’t clear if Epstein’s extensive discussions with them ultimately generated any deals. But the documents nonetheless show how the rise of the China market beckoned Epstein, who made much of his money from advising billionaires such as former Victoria’s Secret owner Leslie Wexner and Apollo Global Management co-founder Leon Black.

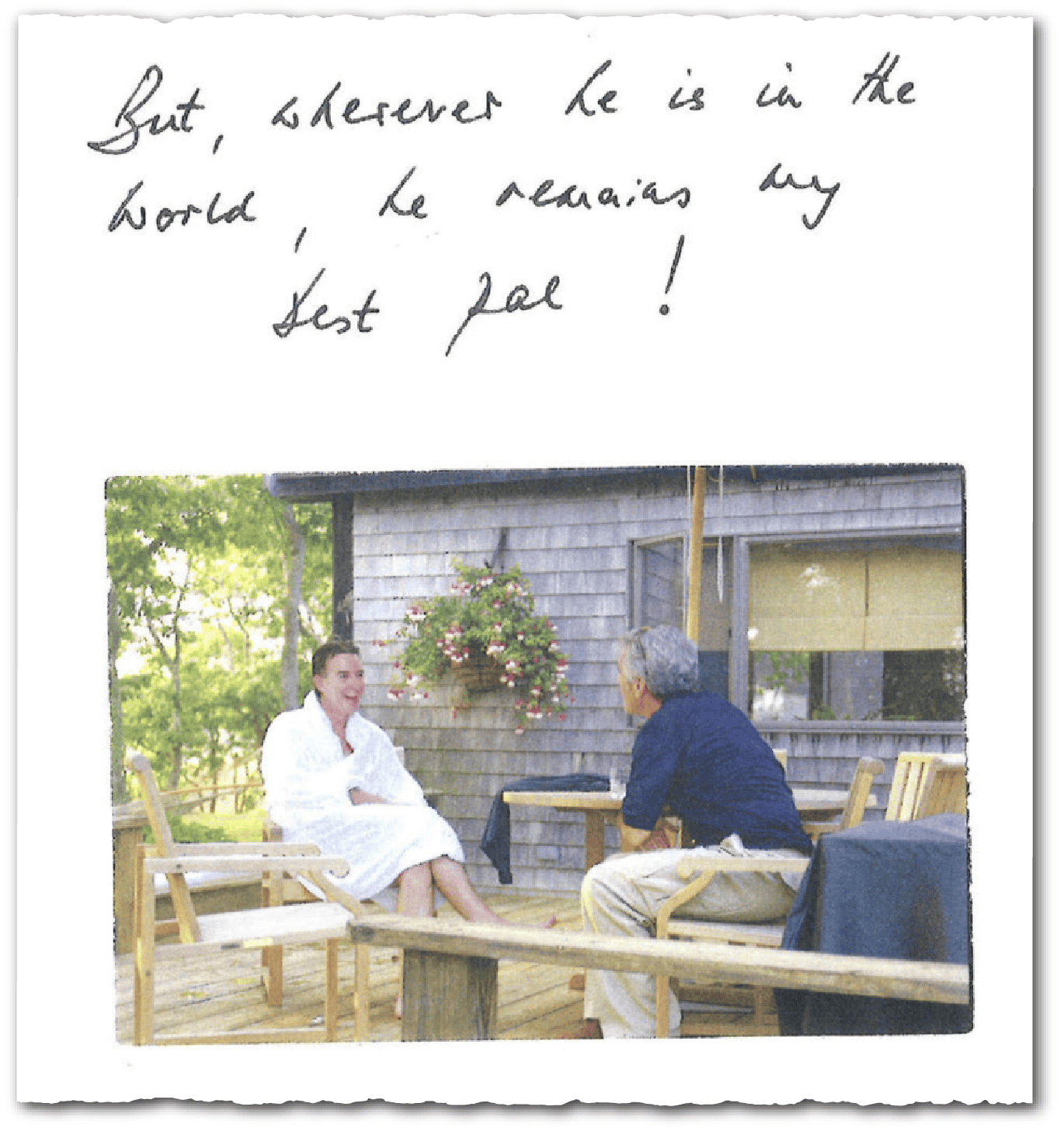

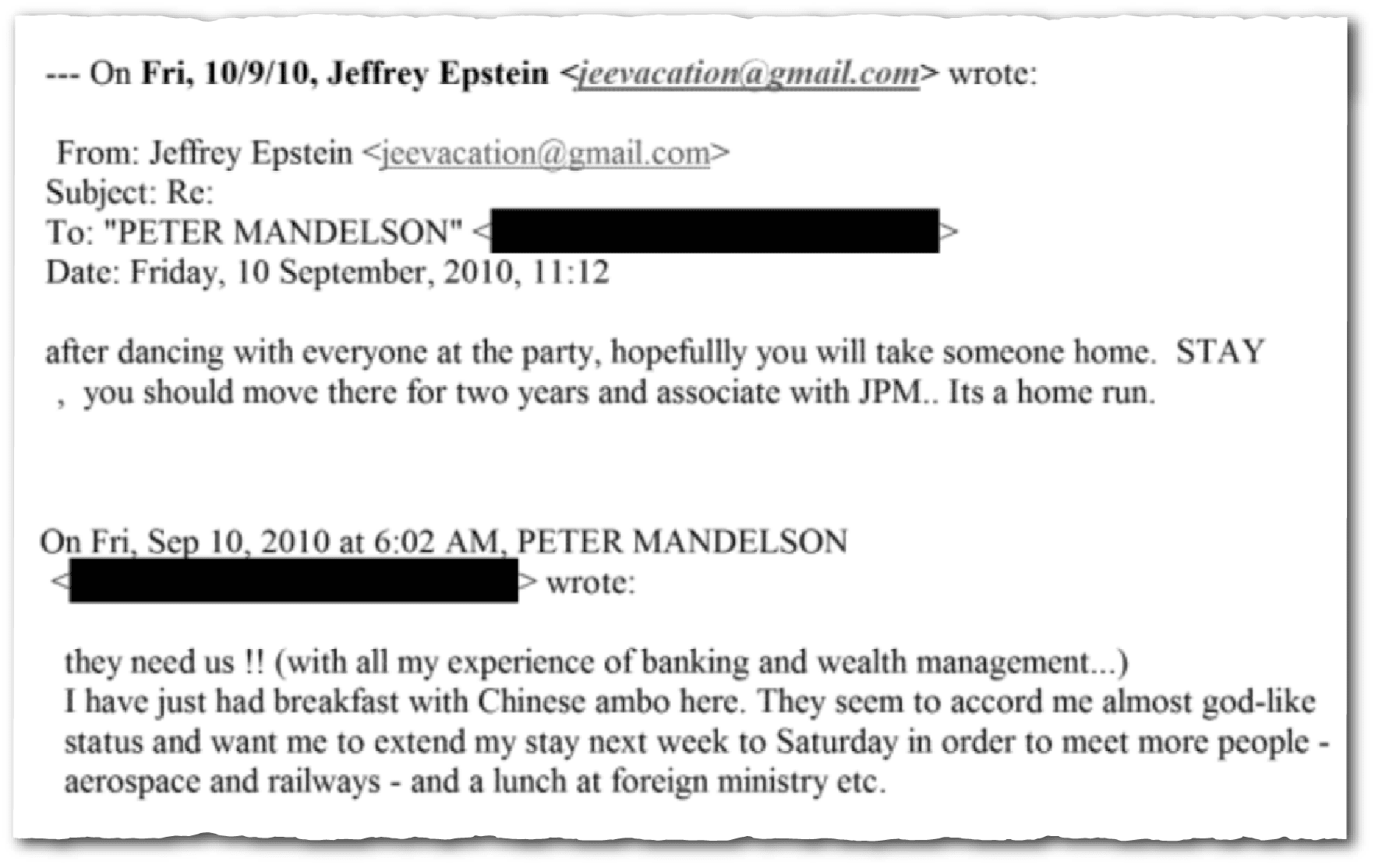

Mandelson, who has called Epstein “my best pal”, discussed China with him as early as 2010, the year Mandelson left his post as business secretary in the Labour government. They stayed in contact until at least 2016, by which point Mandelson had stepped away from public office and founded the lobbying firm Global Counsel. Mandelson continued to visit China regularly.

The emails also show how Mandelson considered himself to be revered by Chinese officials: in between visits in 2010, he described being accorded “almost god-like status”.

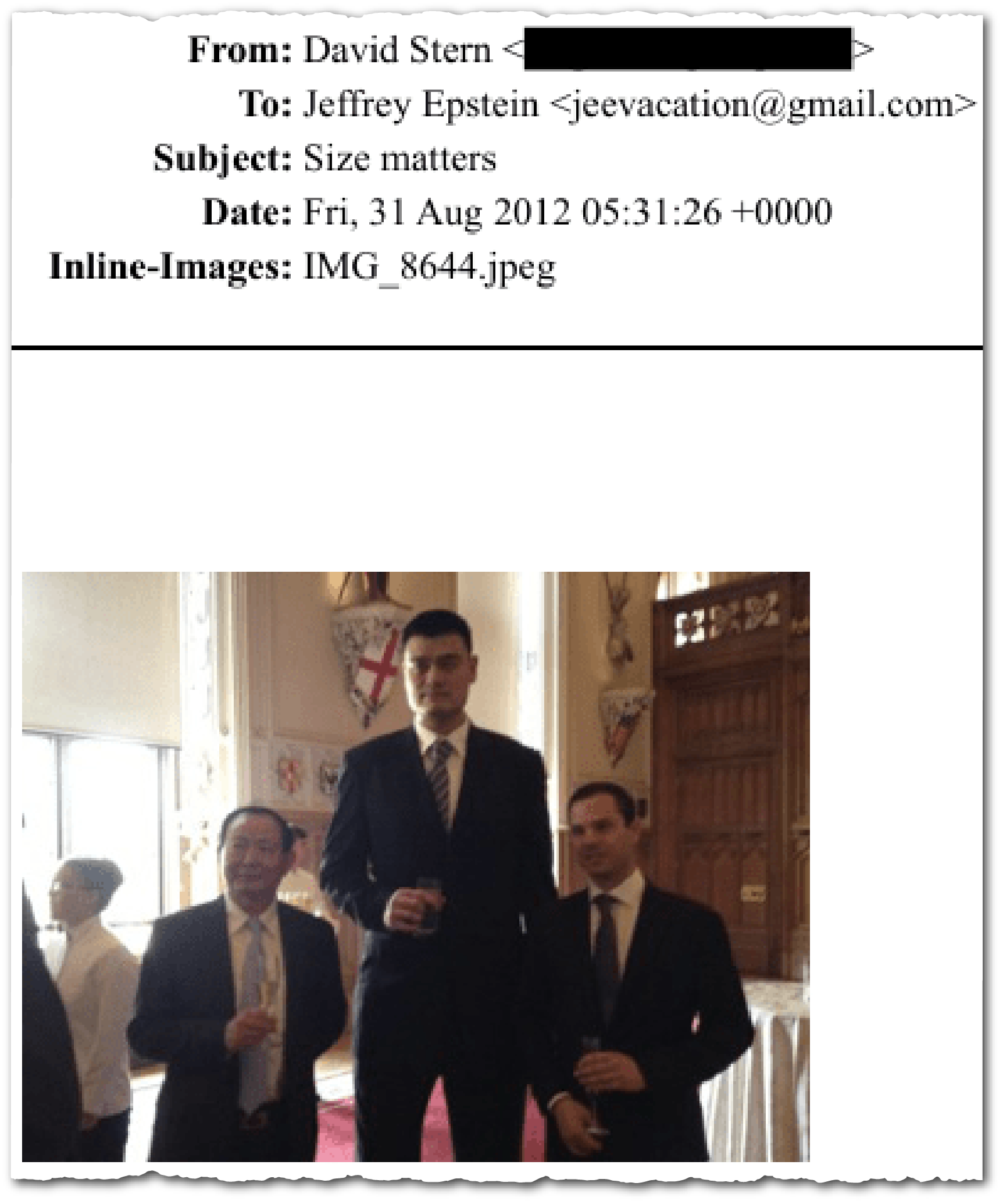

But most of Epstein’s potential dealings in China were pitched by Stern, a German entrepreneur who claimed to have relationships with China’s business and political elite.

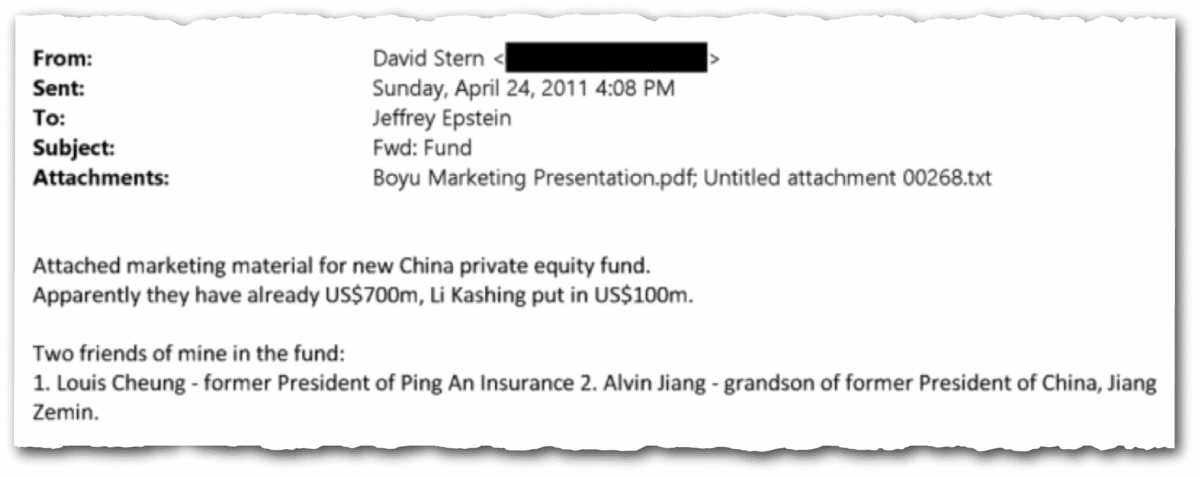

In one exchange, Stern forwarded Epstein information about Boyu Capital, the Chinese private equity firm co-founded by a Chinese “princeling”. Stern called two of its executives, Louis Cheung, the former president of Ping An Insurance, and Alvin Jiang, the grandson of China’s former top leader Jiang Zemin, his “friends.”

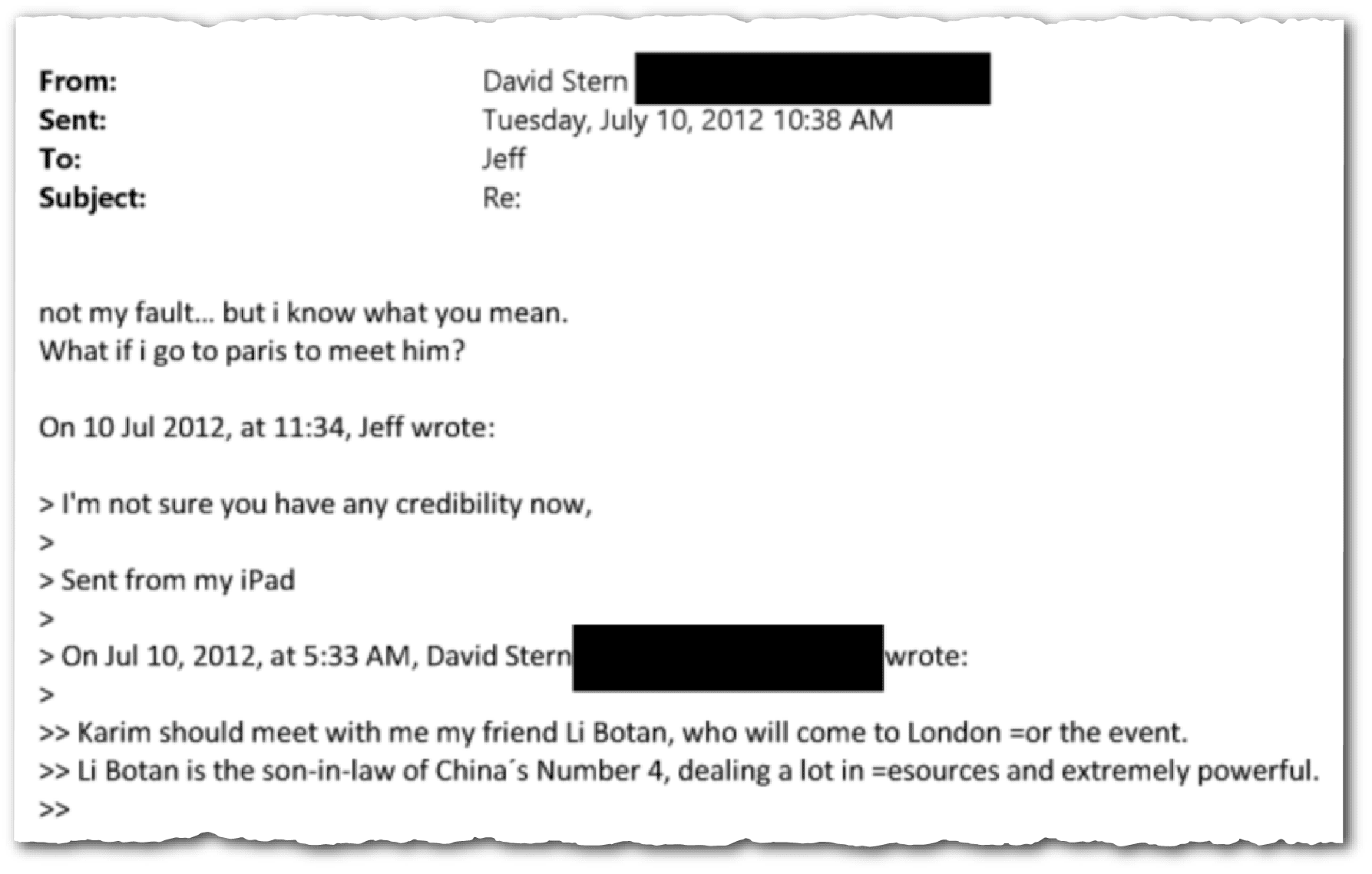

Stern has also invested in projects with Li Botan, the son-in-law of Jia Qinglin, once the Chinese Communist Party’s fourth highest-ranked official.

Mandelson did not respond to phone calls or requests for comment sent by email and Whatsapp. Stern did not respond to requests sent to an email and phone number that appear in the DOJ documents. Cheung, Jiang and Boyu Capital also did not respond to requests for comment.

EPSTEIN AND STERN: 2008–2012

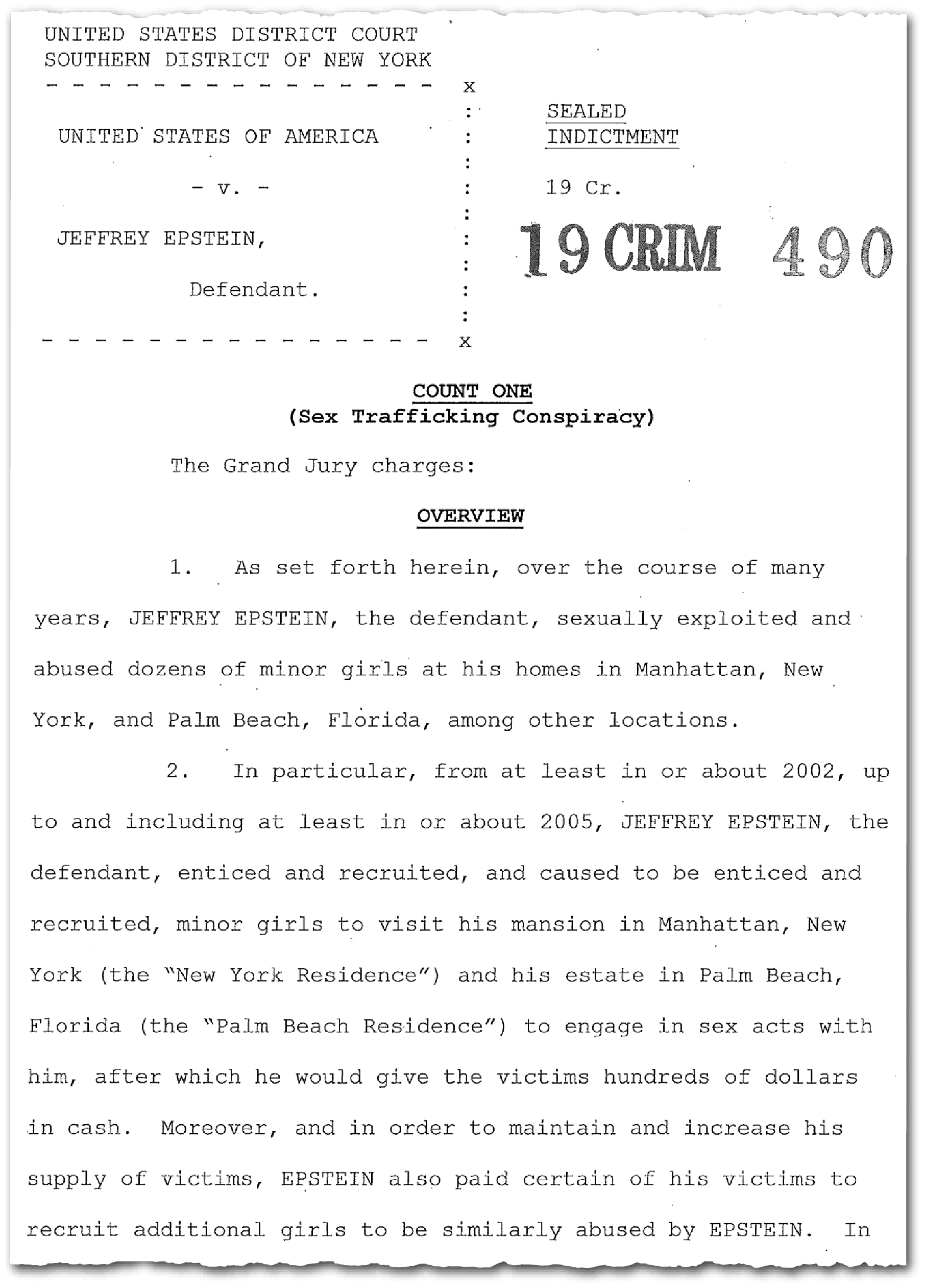

Epstein’s correspondence with Stern appears to have begun in 2008, weeks before Epstein pled guilty to soliciting a minor for prostitution in Florida, and continued until 2019, when he died in prison while awaiting trial on federal sex trafficking charges.

Stern, per his own description to Epstein, studied Chinese law at the SOAS University of London and worked briefly for Deutsche Bank’s and Siemens’ China operations in the late 1990s. He founded UK-registered Asia Gateway Limited in 2002, a “strategy advisory business” with offices in Beijing and London, followed in 2006 by Asia Gateway China, a Beijing-based healthcare IT business. (Filings with the UK’s business registry show that Asia Gateway Limited was not incorporated until 2005.)

In one of their earliest exchanges, Stern, then 30, tried to get Epstein to invest in AGC Capital, a China-focused private equity fund that he was launching. In subsequent years, he continued to pitch all kinds of investment opportunities to Epstein, ranging from a CHF 90 million castle in Switzerland to bringing a private security firm to China to “train local forces”.

He offered to get Epstein tickets to a “special Chinese catwalk” at London Fashion Week so that Epstein could “review Chinese P”. On Epstein’s birthday one year, Stern wished the convicted sex offender a “year full of health, money, and lots and lots of P pre-expiry date”.

Between these exchanges, Stern invited Epstein to be the godfather of his newborn child. Epstein declined.

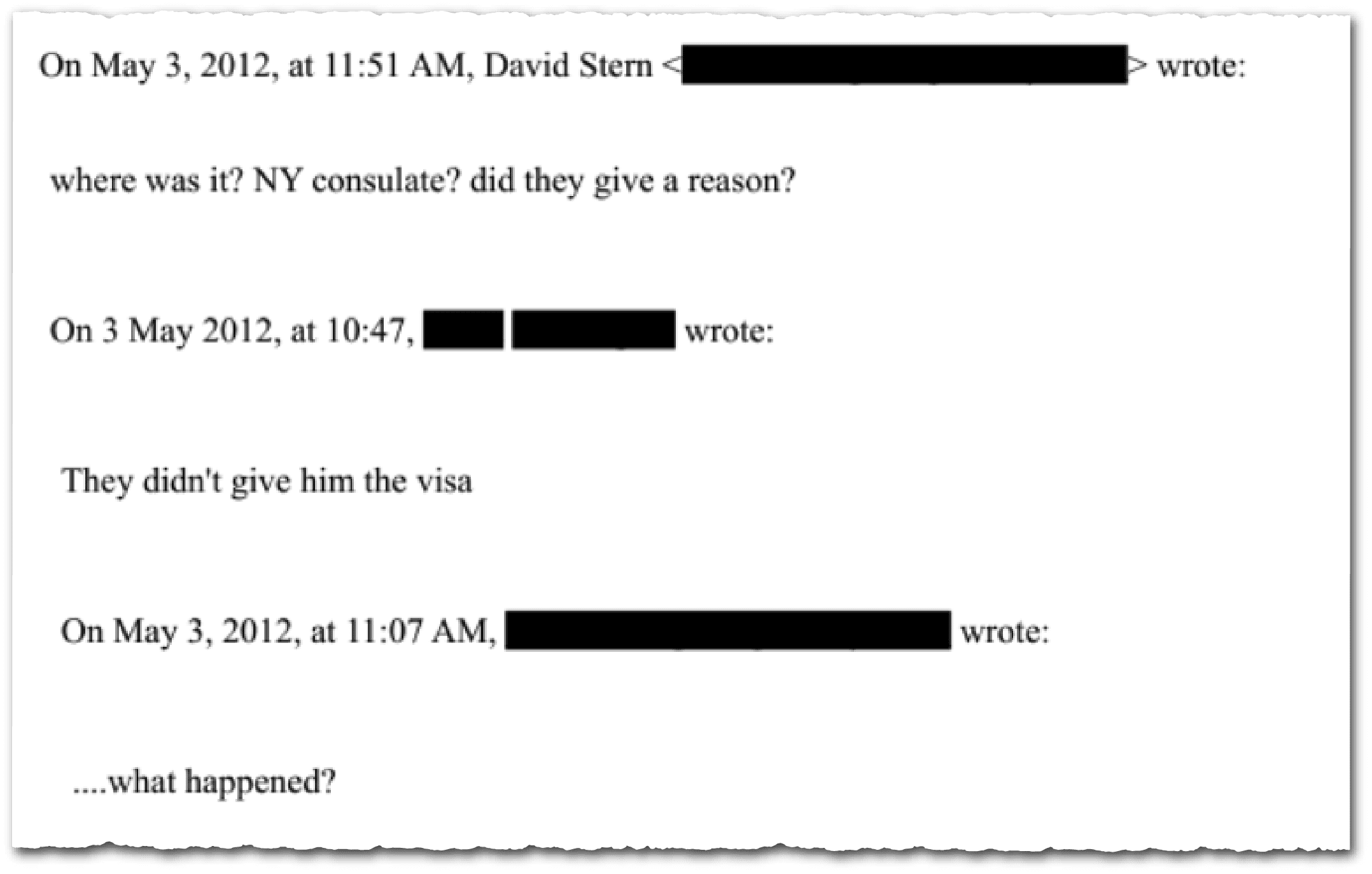

He also tried to help Epstein get a visa to visit China, advising, after the New York consulate denied Epstein’s initial application, that “it will be better not to tick the boxes re. being denied previously or criminal charges”.

In late 2009, the two men began discussing a China venture. “We can do some powerful deals when partnering with China to co-invest abroad, but we need to start the process soon,” Stern wrote to Epstein in October.

Days later, as Stern flew to New York, Epstein tried to set up a meeting between Stern and Jes Staley — head of JPMorgan’s private bank at the time — and instructed Stern to “prepare a one hour presentation on what jes should know to set up a j.p. morgan business in china”.

Epstein’s long-standing relationship with JPMorgan is well documented. The bank processed almost $1.3 billion in transactions for Epstein and his associates, according to investigators for Senator Ron Wyden, the top Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee.

Stern also suggested strategies for the venture with JPMorgan, such as having Epstein pledge a large amount of money to give the operation credibility.

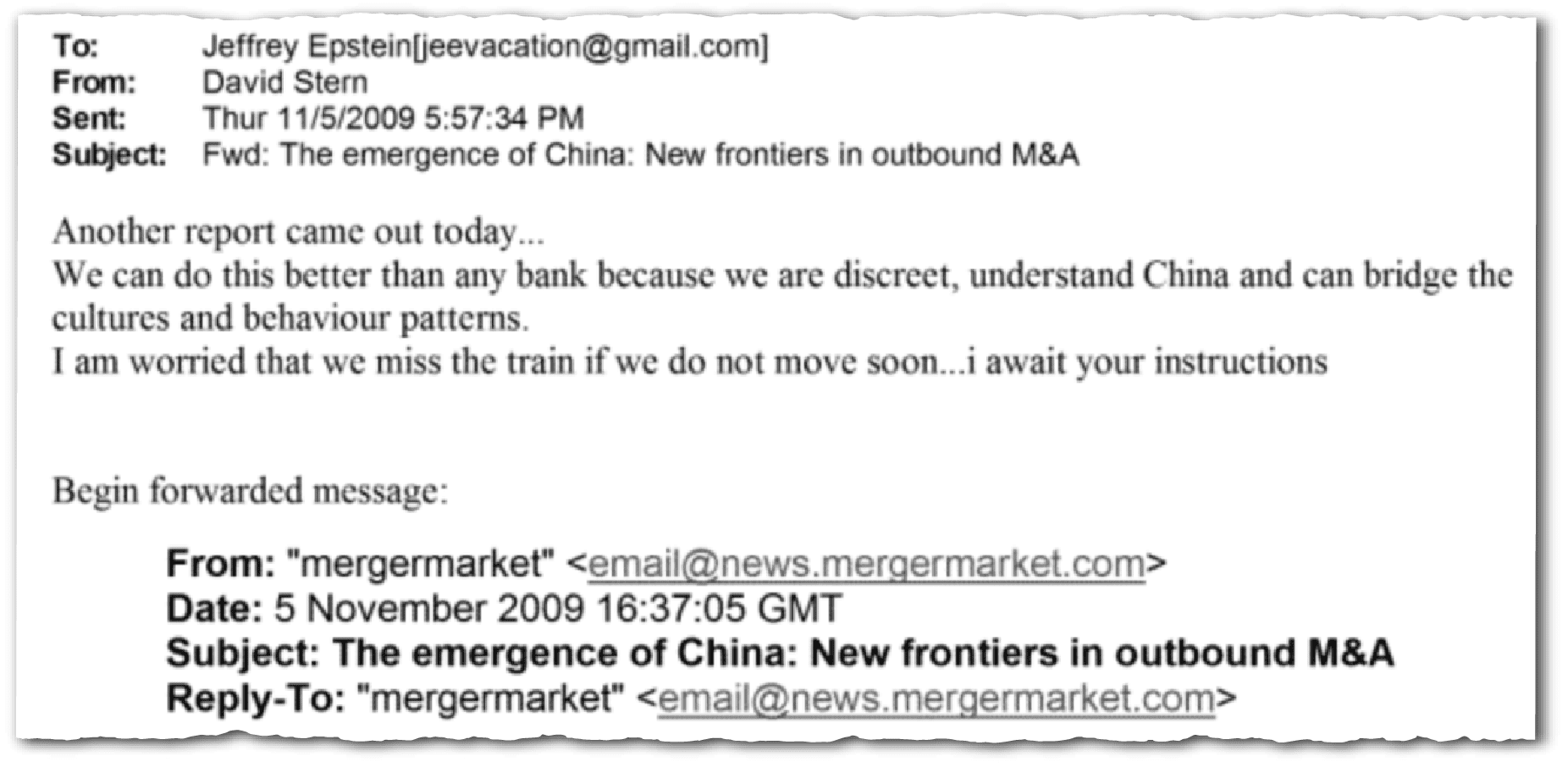

“I am worried that we miss the train if we do not move soon,” Stern urged.

Epstein also introduced Staley to world leaders and billionaires including Sergey Brin, Bill Gates, Elon Musk and Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, the chief executive of Emirati ports firm DP World. Staley, in turn, defended Epstein for years, even as other executives grew uneasy about the bank’s relationship with him. JPMorgan terminated Epstein as a client in 2013, after Staley left the bank.

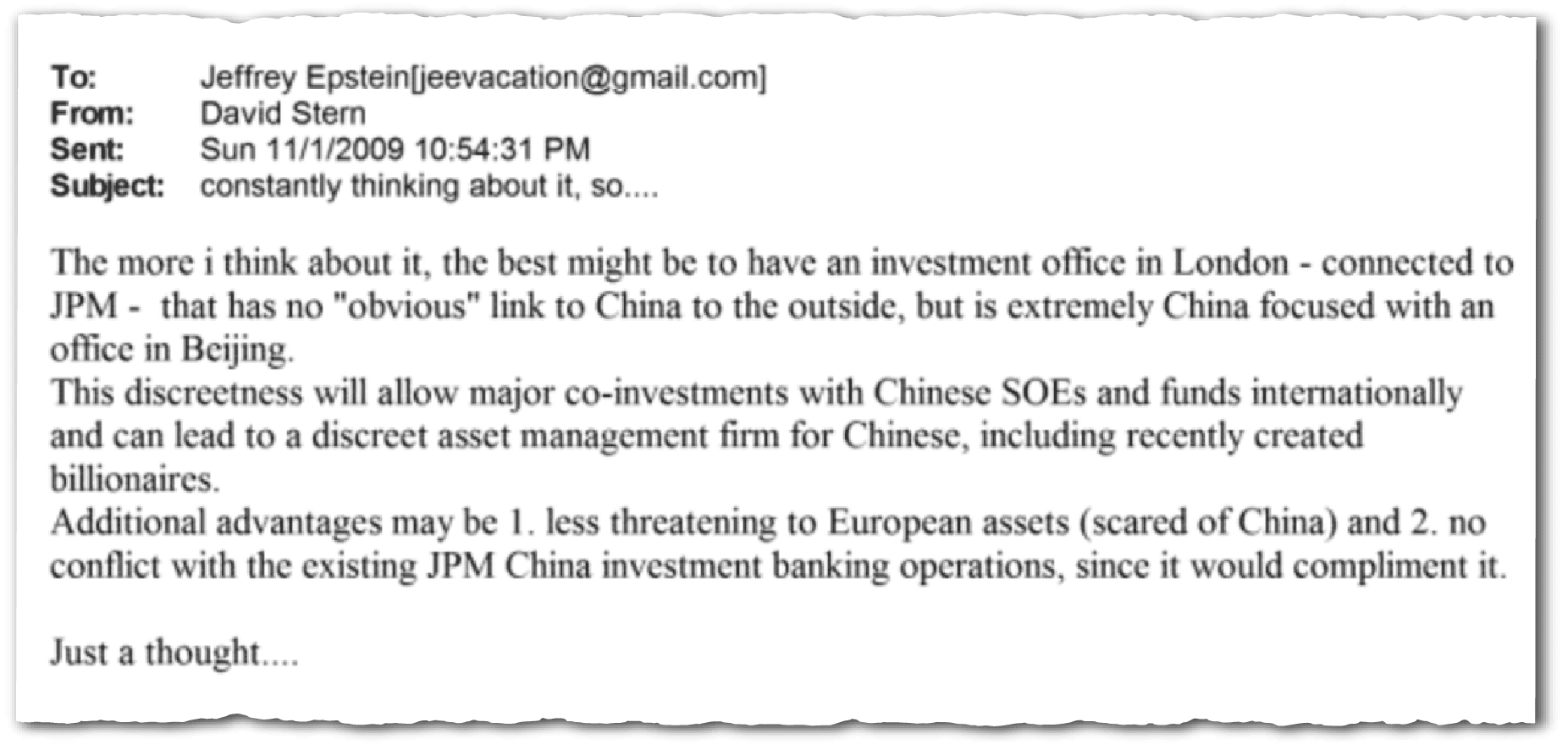

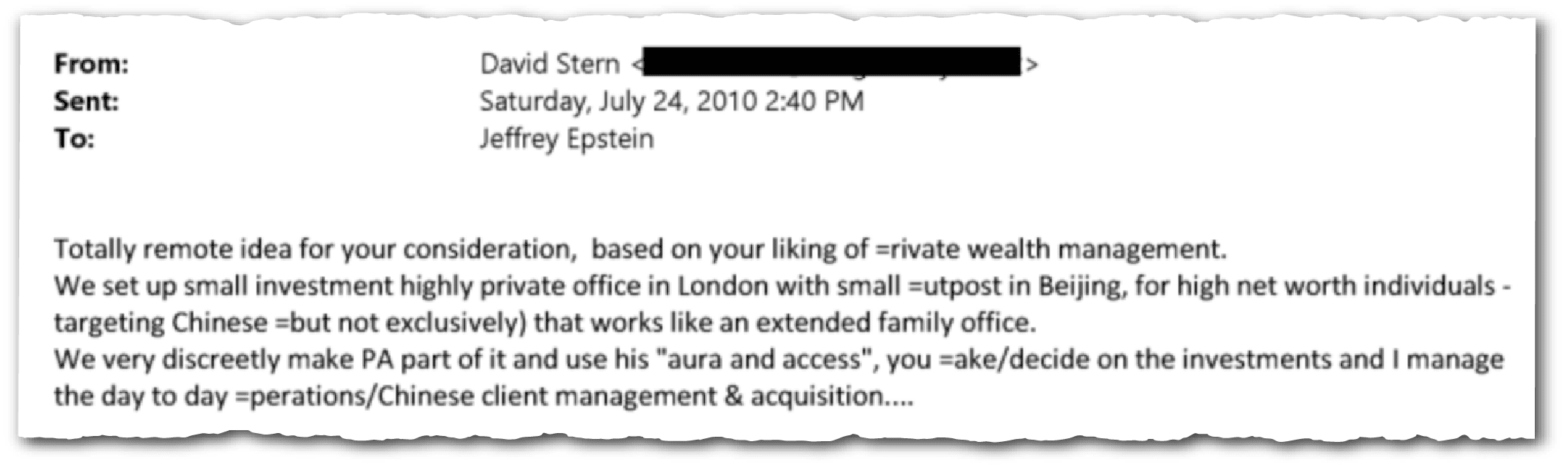

In November 2009, Stern proposed to Epstein that they set up an investment office in London that could be “connected to JPM”.

The office, he suggested, should have “no ‘obvious’ link to China to the outside, but is extremely China focused with an office in Beijing”.

“This discreetness,” he added, “will allow major co-investments with Chinese SOEs [state-owned enterprises] and funds internationally and can lead to a discreet asset management firm for Chinese, including recently created billionaires.”

Days later, Stern told Epstein he was scheduled to meet with Levin Zhu, the chief executive of China International Capital Corporation (CICC) and son of former premier Zhu Rongji, in Beijing.

Stern also suggested strategies for the venture with JPMorgan, such as having Epstein pledge a large amount of money to give the operation credibility.

“I am worried that we miss the train if we do not move soon,” Stern urged.

A spokesperson for JPMorgan declined to comment.

EPSTEIN, MANDELSON AND DESMOND SHUM: 2011–2017

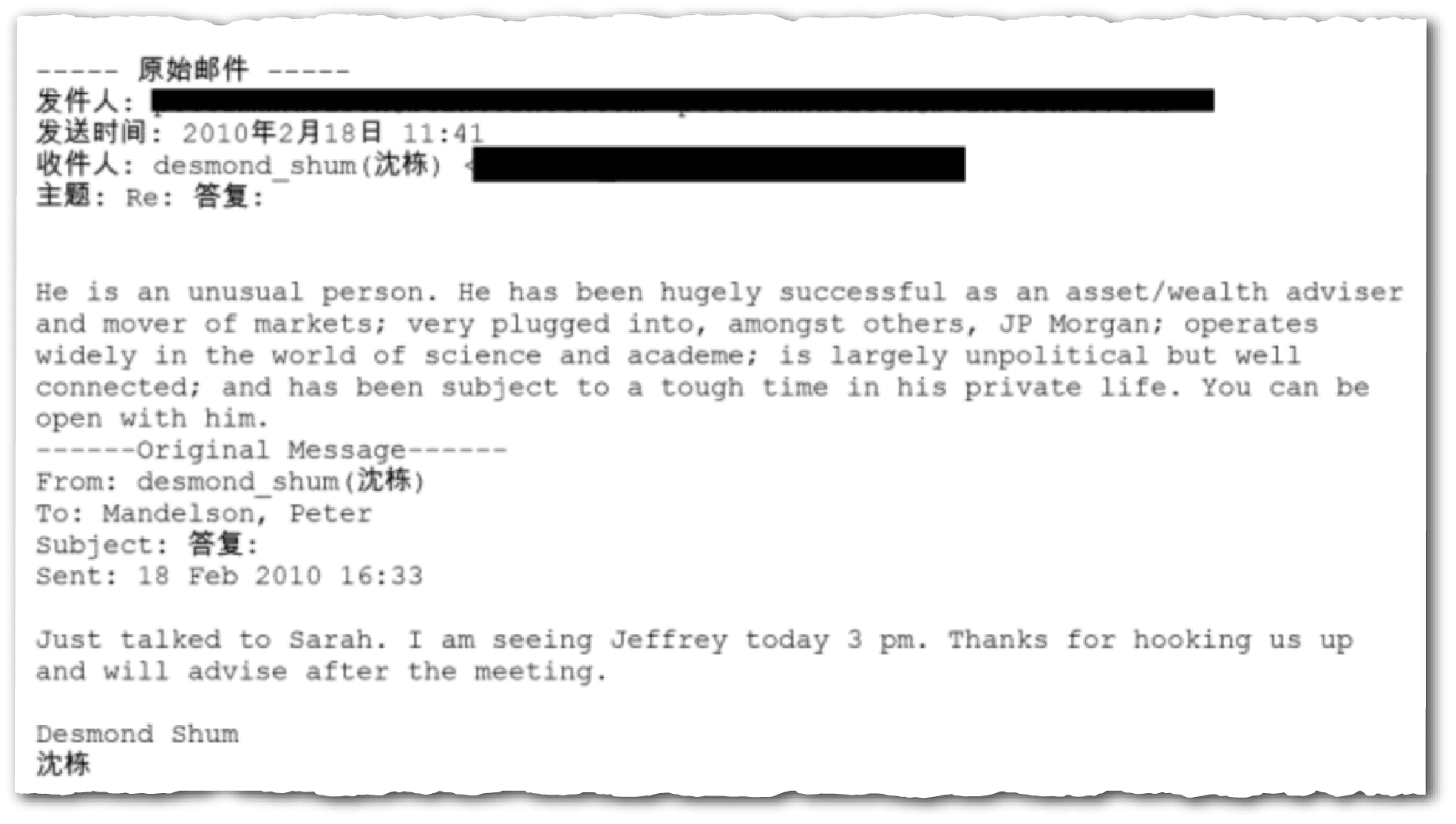

Around this time, Mandelson — then still a UK cabinet minister — reached out to Epstein with an introduction, suggesting that he meet with his “friend” Desmond Shum.

Shum, who would later write the Chinese political exposé Red Roulette, was at the time a businessman and real estate developer in Beijing. He was married to Duan Weihong, an entrepreneur who helped the family of then premier Wen Jiabao conceal billions of dollars worth of shares in Ping An Insurance, as revealed by a New York Times investigation in 2012.

Before the meeting, which took place in New York in February 2010, Mandelson told Shum that Epstein was “an unusual person” who had “been subject to a tough time in his private life”.

That September, Mandelson asked Epstein to “nurture” his relationship with Shum, whose ventures included a logistics hub attached to Beijing’s main airport.

In April 2011, Shum and Epstein discussed creating an “offshore banking” business in China, using Shum’s political connections. Shum told Epstein that he had talked about the idea with the chairman of state-owned investment firm CITIC, the vice mayor of Shanghai, and a “top decision maker” at the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE).

“What was discussed between you and I will be an exception in China and thus the first, but it is doable,” Shum wrote to Epstein. “I will need to pull resources and get approvals from SAFE, from Shanghai municipal government, and from a state owned bank to make this happen, but I can make it happen.”

Shum flew to meet Epstein in Paris in May, the emails suggest. “We need your involvement, probably with your support staff, to move forward,” Shum wrote at the end of the month.

“I am swamped,” Epstein responded.

In April 2011, Shum also asked Epstein if he was interested in joining a 1.5 billion euro “minority transaction” for an unnamed luxury consumer brand. “I invest in anything that will likely make money,” Epstein responded, claiming access to more than $15 billion. “That is my only criteria.”

Prada went public in Hong Kong two months later, raising the equivalent of 1.5 billion euros.

The men stayed in contact over the next several years. In 2013, Shum sent Epstein a fundraising deck for his firm Great Ocean — which had held shares in Ping An on behalf of Wen’s family — with the goal of raising money for a plan to develop infrastructure near three to five additional airports.

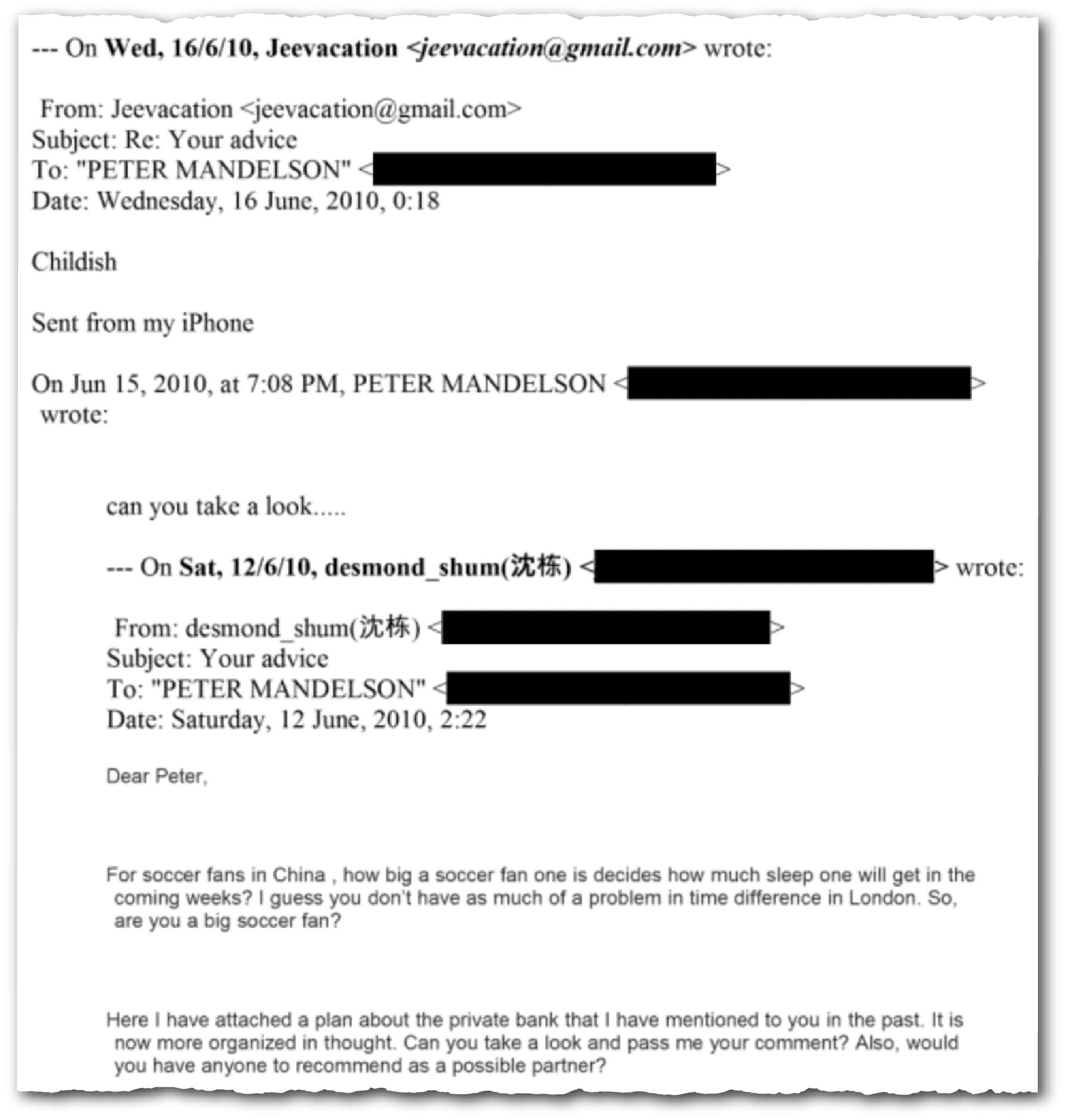

Epstein seemed skeptical of some of Shum’s other ideas. In one case, in an email to Mandelson, he dismissed Shum’s plan for a private bank as “childish”. And while they continued to schedule catch-ups through 2017, there is no evidence from the documents that Epstein and Shum’s relationship developed further or that they completed any deals together.

Shum said in a statement to The Wire China: “I have had no business transaction or money transaction of any kind with Mr. Jeffrey Epstein.”

In May 2010, Mandelson left public office after the Labour Party lost the UK general election. Over the next year, Epstein advised Mandelson on how to attract high-paying non-UK customers to Global Counsel. Emails show that CICC, the state-owned investment bank, was one of the potential clients Global Counsel pursued. The emails were first reported by The Guardian last week.

Global Counsel did not respond to requests for comment.

In an exchange between Epstein and Shum in November 2010, Shum described “Peter” — presumably Mandelson — as “now a regular in Beijing”.

“They need us!!” Mandelson had written to Epstein earlier that year, after a lunch with the Chinese ambassador to the UK. “They seem to accord me almost god-like status and want me to extend my stay next week to Saturday in order to meet more people – aerospace and railways – and a lunch at foreign ministry etc.”

In April 2011, Mandelson wrote to Epstein: “I appreciate your advice. But I am starting in political world, moving to financial. Learning. Making contacts. Establishing new credentials and a business platform. Some Chinese want deals (should be able to offer that in due course). Some have deals already but need hand holding. Some want to put money into funds. CICC retain us cos think we have something to offer Chinese.

“Henry K says we also need to become go-betweens for those with commercial disputes,” he added in an apparent reference to Henry Kissinger.

EPSTEIN, STERN AND MOUNTBATTEN-WINDSOR: 2010–2019

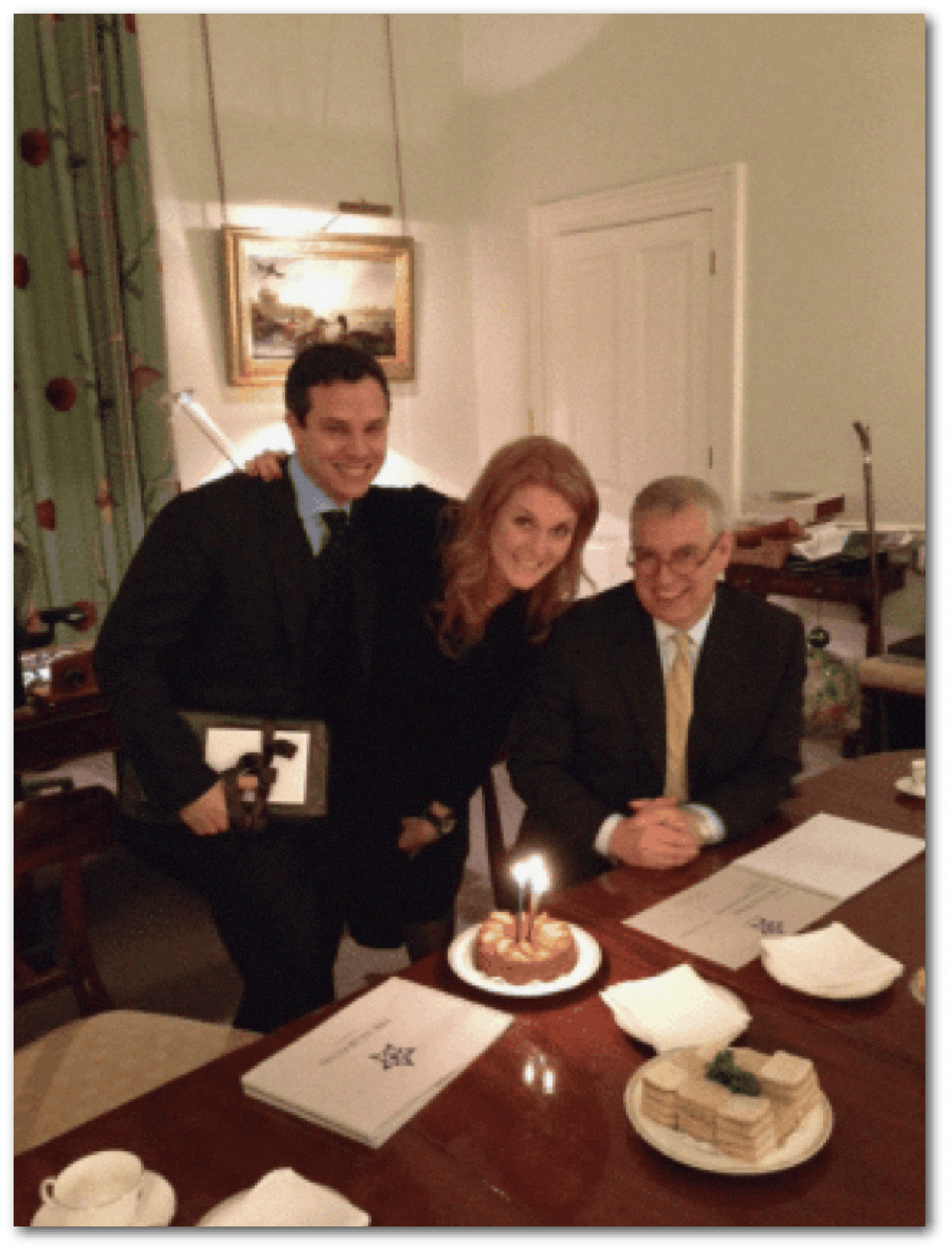

Meanwhile, the emails suggest Stern had become acquainted with Mountbatten-Windsor’s ex-wife, Sarah Ferguson, through Epstein.

In February 2010, a contact whose name appears only as Sarah recommended that Stern help someone named “A” set up a wealth fund in China. “He has been helping me a great deal with an ear and advice to my way ahead. He has a great roladex [sic] for China,” Sarah wrote.

Stern followed up with an email to “A,” writing: “Your Royal Highness, The Duchess has asked me to get in contact with you. It would be a pleasure to discuss with you how I may be of help in this matter.”

Later that year, Stern started trying to bring Mountbatten-Windsor into some of the deals he pitched to Epstein.

In July 2010, he suggested setting up a private office in London with an outpost in Beijing to manage the assets of high net worth individuals. “We very discreetly make PA part of it and use his ‘aura and access’,” Stern wrote, in an apparent reference to then Prince Andrew. While Epstein made decisions on investments, Stern said he would manage daily operations.

In September, an exchange between a redacted email address and Epstein referred to Stern’s firm Asia Gateway as one that “manages private PA deals”.

The next month, Stern proposed doing “wealth management for Chinese with JPM”, suggesting that they partner with Chinese media mogul Bruno Wu and involve “PA”.

Stern would go on to become an aide to Mountbatten-Windsor and served as a director from 2017 to 2019 at his company Pitch@Palace Global, which linked startups with investors.

Mountbatten-Windsor’s knowledge of Stern’s pitches is unclear. He has previously said that he last was in contact with Epstein was 2010, although the emails contradict this.

Buckingham Palace referred The Wire China’s inquiry to Mountbatten-Windsor and said it “does not operate or speak for him in any capacity”. Mountbatten-Windsor could not be reached for comment.

EPSTEIN, STERN AND JPMORGAN EXECUTIVES: 2011

Stern and Epstein pressed forward with their ambitions to work with JPMorgan in China in early 2011. An email from Epstein indicated that someone named “jess” — presumably Jes Staley — suggested a structure that would allow Stern’s company to get involved in JPMorgan deals while continuing to work with “PA”.

Over the following months, Epstein and Stern discussed various ways to formalize a partnership. Epstein suggested that Stern add a JPMorgan representative to his company’s board to give the bank “total transpar[e]ncy, and effective oversight.”

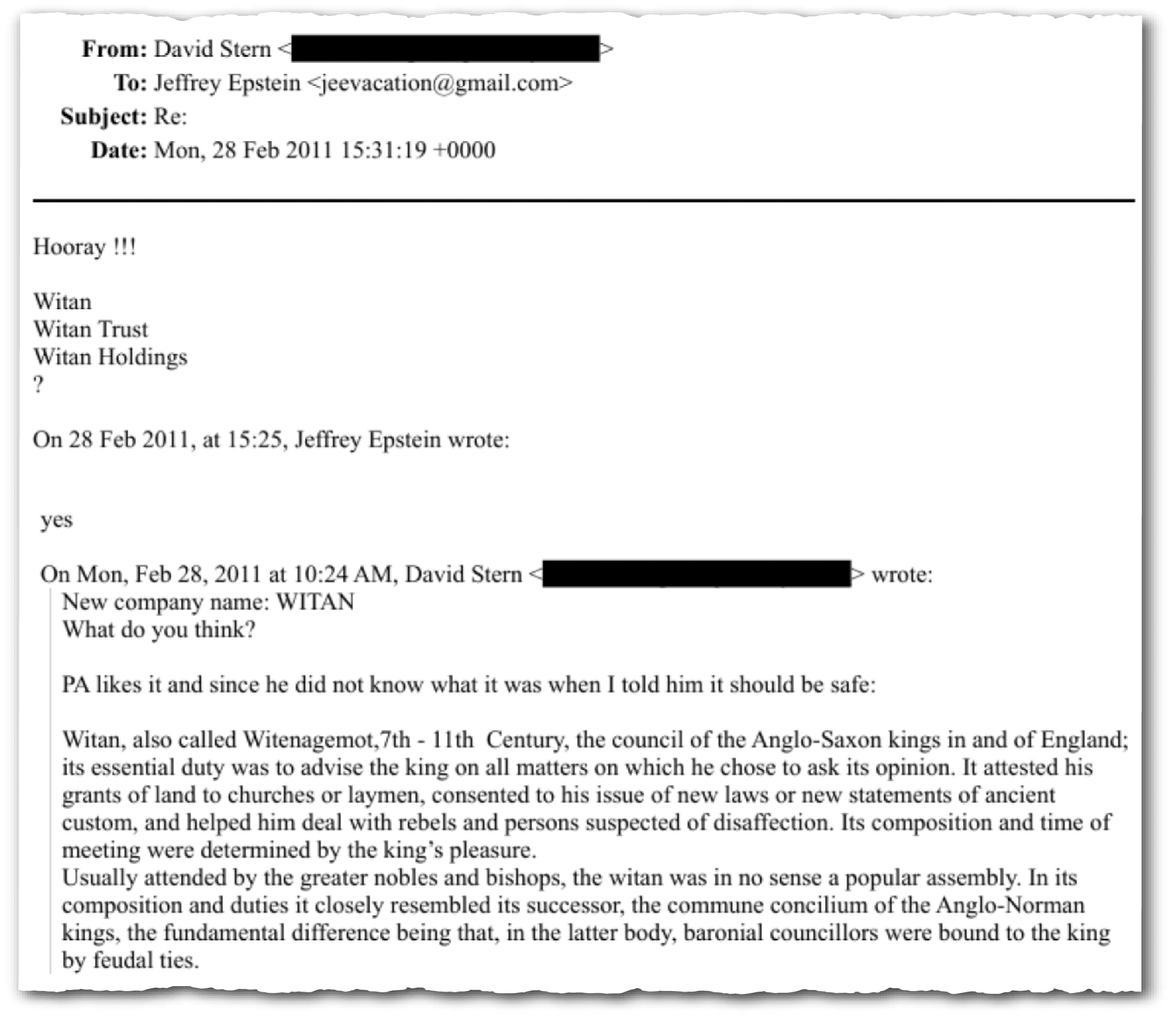

Around this time, Stern changed the name of his UK company from Asia Gateway to Witan Group and registered firms with the same name in Hong Kong and Beijing. The name, Stern said in an email to Epstein, was inspired by a council that advised the King of England during the Early Middle Ages. “PA likes it,” Stern added.

Staley also helped Stern make connections at JPMorgan, the emails show.

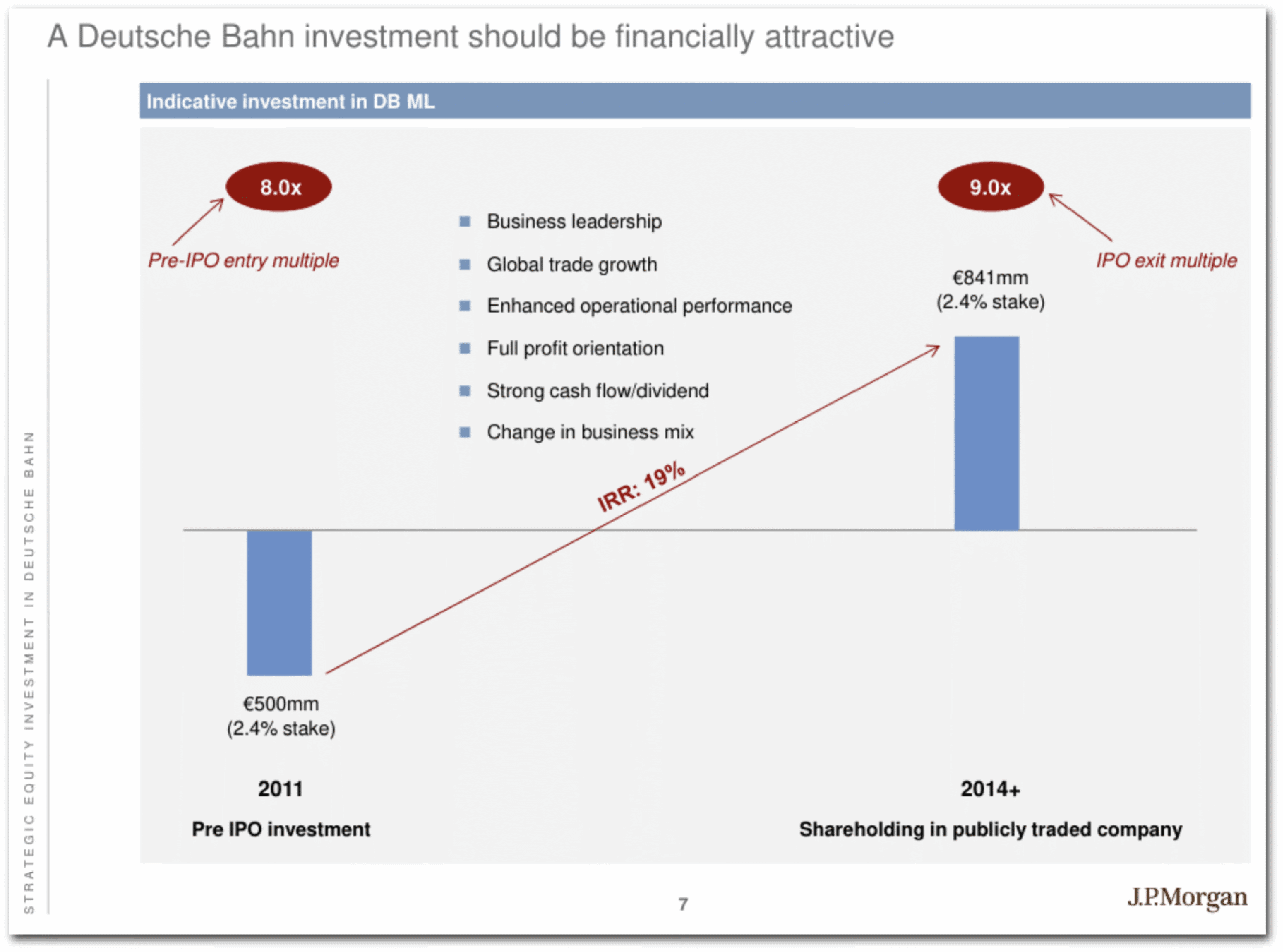

In February 2011, Stern met with Larry Slaughter, one of JPMorgan’s top bankers in Europe, and discussed an investment opportunity involving Deutsche Bahn.

The state-owned German railway company was exploring a partial privatization after a failed bid to publicly list in 2008. At the time, China Investment Corp., the newly established Chinese sovereign wealth fund, had expressed interest in acquiring a stake.

Emails show that Slaughter was looking to leverage Stern’s connections in Beijing to secure an investment in Deutsche Bahn from Chinese state investors.

After Slaughter sent Stern a pitch deck for Deutsche Bahn in March 2011, Stern requested Epstein’s permission to ask Slaughter to remove JPMorgan’s logos from it. Epstein also advised Stern on how to approach the deal and suggested edits to the deck, which Slaughter’s team then made.

Slaughter and Stern continued to exchange emails for several months. “Three strong potentials in China depending on the final offering,” Stern wrote to Slaughter in May 2011. After Slaughter informed Stern in June that the deal had run into delays, Stern wrote to Epstein: “Not good since CIC and [insurance company] China Life was ready to look at it and I told them they could.”

Stern was not a money guy. He was a broker of connections … Somebody told me that he’s the best networker in the world, and that was my experience. These princeling links … he did know many of them.

a person who previously worked with Stern

The deal never happened. Slaughter changed roles at the bank that summer and the German government ultimately abandoned its privatization plan for Deutsche Bahn.

Slaughter, who is now retired, did not respond to requests for comment.

EPSTEIN, STERN AND INFLUENTIAL CHINESE “FRIENDS”: 2011–2017

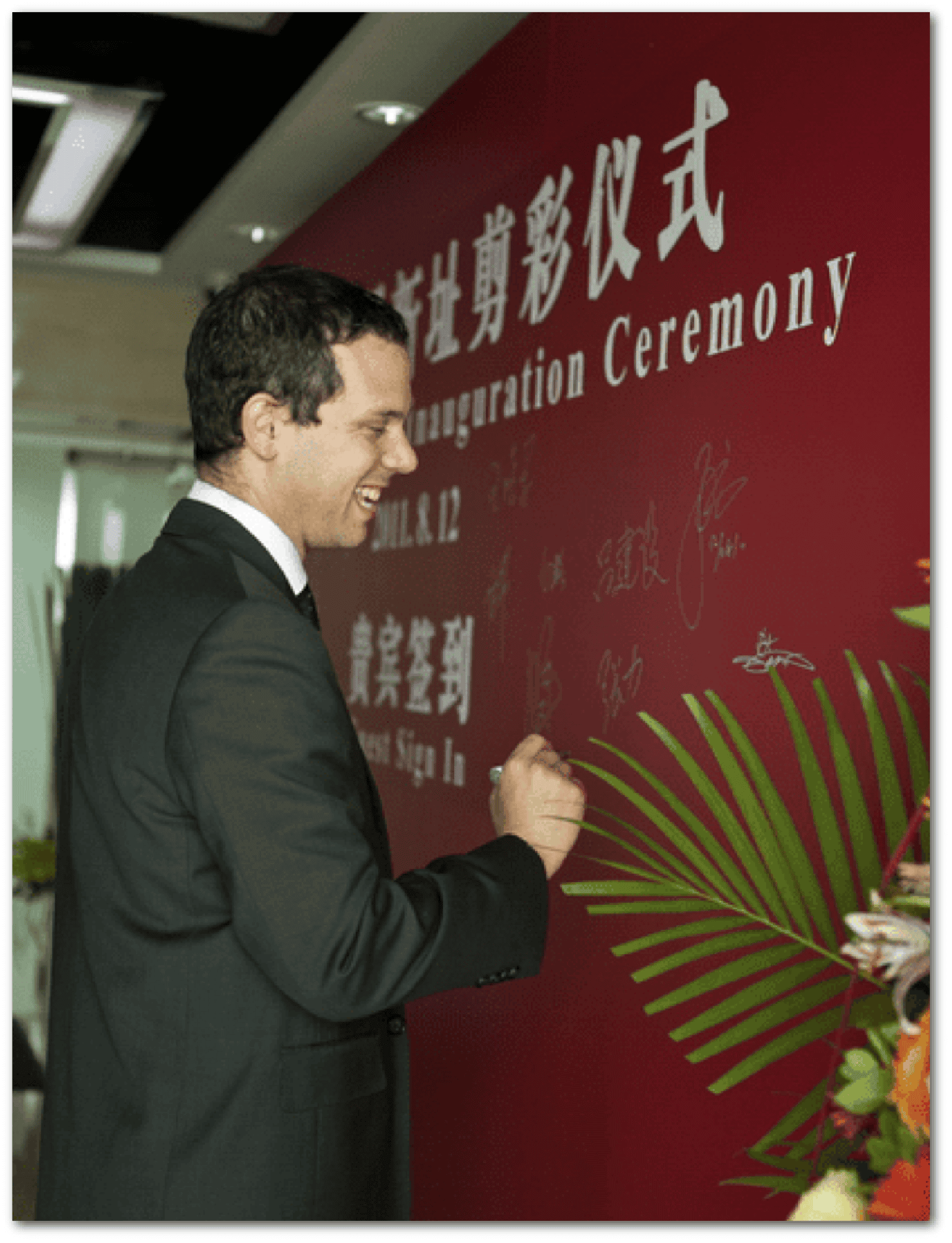

During this time in 2011, Stern was also writing to Epstein about other relationships he was trying to build in China, including with the so-called princeling offspring of China’s political elite.

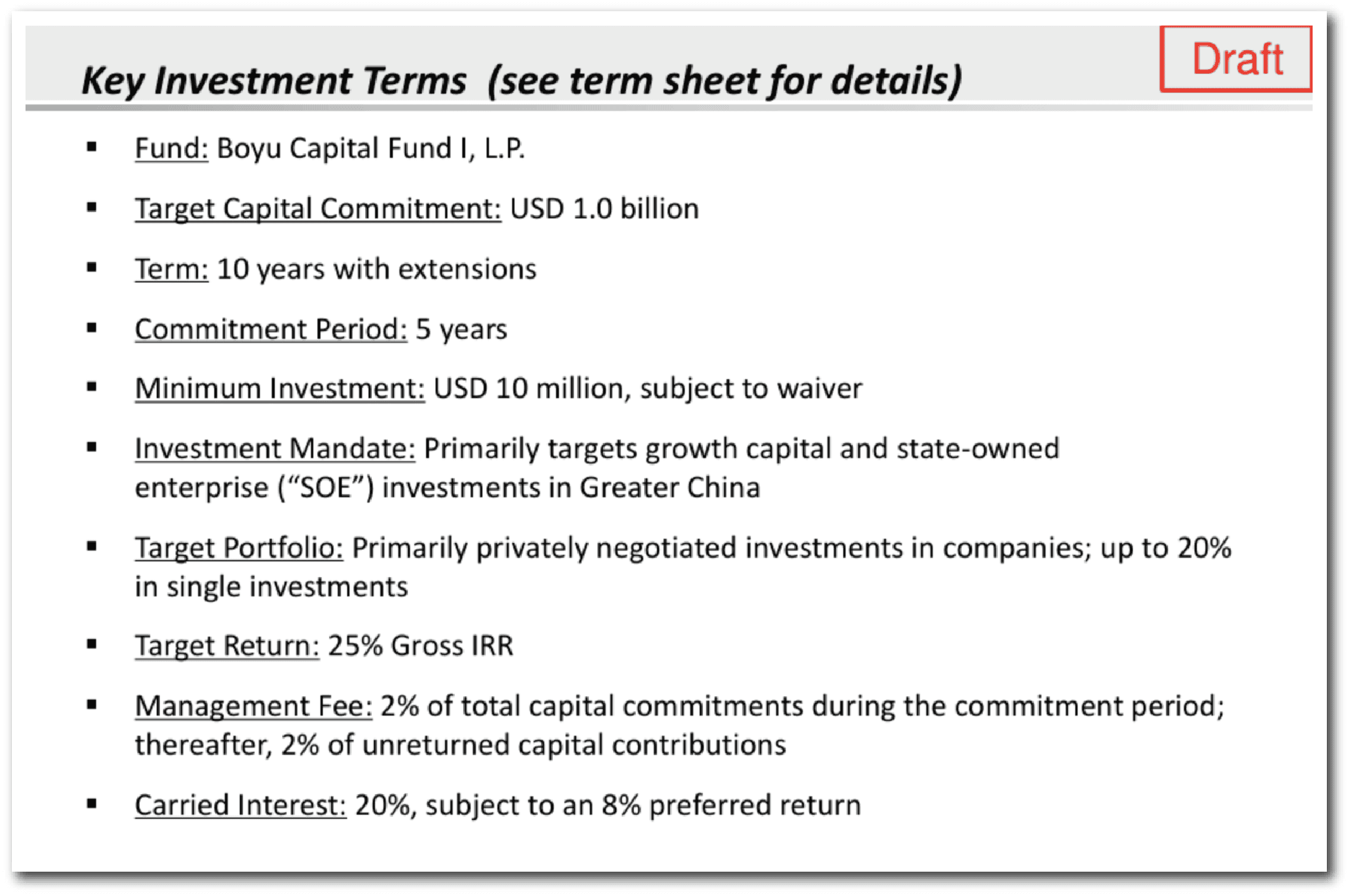

In April 2011, Stern shared a Boyu Capital pitch deck with Epstein for its inaugural fund, which boasted of a “proprietary deal flow” due to an “industry network based on ‘first-call’ status”, and gave a target return of 25 percent. Stern didn’t say where he got the deck. It was in this email that he boasted of being “friends” with Alvin Jiang and Louis Cheung, who became Boyu’s chief executive.

“I am discussing the set up of an investment vehicle/fund with the son of the Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao,” Stern wrote to Epstein in January 2012. “This would be the killer for JPM, but if they [don’t] do it then we should do it without them.”

“My friend will probably become Finance Minister,” Stern wrote the following month, without specifying who he was referring to. “[The] second largest government owned Chinese asset management firm will [p]robably appoint me on advisory board on its alternative investment arm,” he added.

The Wire China did not find evidence that any of these relationships Stern boasted to Epstein about generated any business. At times Epstein appeared to grow frustrated with Stern. “I’m not sure you have any credibility now,” Epstein wrote Stern in 2012, after the German entrepreneur pitched a meeting between Li Botan and an Epstein friend — the son of a Senegalese president.

But Epstein did not fully lose faith in Stern. As a Bill Gates-backed nuclear energy startup pursued Chinese partners in 2013, Epstein forwarded dealmaking advice from Stern to Boris Nikolic, Gates’ science advisor, and later instructed Stern: “Write a full proposal.”

The start-up, TerraPower, closed a deal with China National Nuclear Corp two years later.

A spokesperson for TerraPower told The Wire it was not aware of discussions between Nikolic, Epstein and Stern, did not ask Epstein to get involved, and never had any “contact or interaction” with Epstein or his colleagues.

“Stern was not a money guy,” a person who previously worked with Stern told The Wire. “He was a broker of connections. He brings people together and earns money from fees on transactions.”

“Somebody told me that he’s the best networker in the world, and that was my experience,” the person added. “These princeling links … he did know many of them.”

In late 2015, Stern sought Epstein’s advice on how to structure a joint venture between Witan and Evergrande, the Chinese real estate giant, referring to its chairman, Xu Jiayin as “a friend of mine”. Stern later represented Evergrande in a proposed GBP 700 million deal to acquire Cala Homes, a UK housebuilder. A June 2016 letter from Evergrande to a Cala investor named Stern as its contact person for negotiations.

But the deal fell through after Beijing tightened capital controls. “These new Chinese government regulations restricting fund outflow are just about to kill my deal 3 weeks before completion,” Stern wrote to Epstein in December 2016. Epstein suggested workarounds. It collapsed the following month.

Stern and Li Botan meanwhile invested together at least once in 2017, in an electric vehicle company called Evelozcity, later renamed Canoo.

The firm was founded by two former executives at Faraday Future, a financially troubled EV company controlled by the one-time Chinese billionaire Jia Yueting. As Faraday neared bankruptcy in 2017, emails show that chief financial officer Stefan Krause, who had worked with Stern on the Evergrande deal, approached Epstein for a bailout. Epstein was skeptical.

After a Chinese court froze Jia’s assets and Faraday abandoned plans to build a U.S. factory, Stern approached Epstein for an emergency loan for Faraday. There’s no evidence in the emails that Epstein agreed.

Krause ultimately quit Faraday, and Stern and Li invested in his next company, Evelozcity, court documents show. Li put in at least $100 million, according to the emails and a person familiar with the matter. Canoo won a contract in 2022 to supply vehicles to NASA. It went bankrupt in 2025.

The person added that Epstein did not invest in either EV company.

Witan Group did not respond to emailed requests for comment. Krause declined to comment for this article. Li could not be reached for comment.

EPSTEIN, STERN AND ROBERT KUHN: 2017–2023

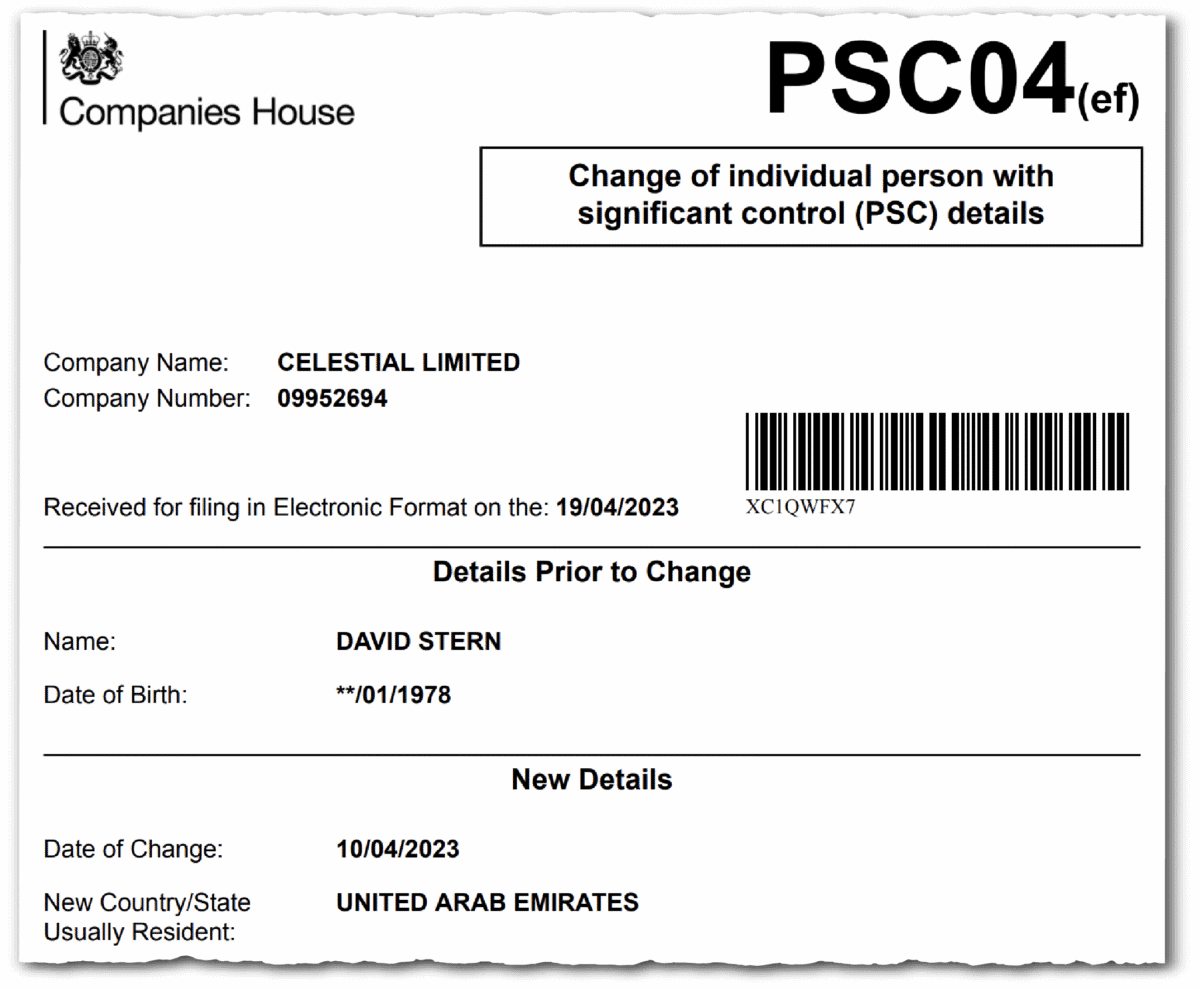

Stern has since pivoted away from China. Witan Group’s mainland business was closed in February 2017, corporate records accessed through WireScreen show, though Stern still listed China as his country of residence in corporate filings in 2020.

In 2023, he changed his domicile to the United Arab Emirates, filings show. Stern was a member of the advisory board of Cambridge University’s Judge Business School until last week, when he resigned. In recent years he consulted for MSG Entertainment and Sphere Entertainment, companies controlled by James Dolan that own the New York Knicks and several concert venues.

In a statement to The Wire, a spokesperson for MSG Entertainment and Sphere Entertainment said: “Mr. Stern was never an employee of the company and is no longer providing consulting services.”

Stern also appears to have continued working with people in Mountbatten-Windsor’s circle.

Amanda Jane Thirsk, who worked for the royal family for more than a decade and eventually became Mountbatten-Windsor’s top aide, joined Witan’s Hong Kong entity as a non-executive director in 2021, corporate records filed with the city’s companies registry show. She resigned soon after.

Stern also continued pitching Epstein even as he faced mounting legal troubles in the U.S.. For years, the two men had discussed a bid for Deutsche Bank with the support of Qatar, whose royal family is a minority shareholder in the firm.

Thirsk is currently the head of international business development at Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com, according to her LinkedIn profile. She declined to comment. JD.com did not respond to a request for comment.

Epstein, on the other hand, maintained a more active interest in China. The emails show he discussed establishing an extension of Tsinghua University in Boston with Gerald Chan, a Hong Kong real estate billionaire, and Harvard math professor Yau Shing-tung — first reported by The Harvard Crimson last month.

Epstein also asked Robert Kuhn, an American banker known for his close ties with the Chinese leadership, to help a Shanghai-based company with a potential sale and government relations, Kuhn recalled in an interview with The Wire.

Emails show that in December 2018 Epstein introduced Kuhn to his associate Nicole Junkermann, the scion of a wealthy German family, who was looking to sell her stake in Really Sports, a Shanghai-based sportswear firm. Kuhn says he placed one call but that his involvement in the deal stopped after the company picked a different investment banker.

Epstein had partially funded a science and philosophy TV show that Kuhn created and hosted on public television, directing his accountant to send separate payments of $150,000 in 2017 and $500,000 in 2018 to a charity Kuhn used to fund the venture1Kuhn says he never received any personal compensation from making the show..

Kuhn told The Wire he was introduced in mid-2016 to Epstein, who was interested in leading-edge science and meeting famous scientists. China comprised only about “five percent” of their conversation, Kuhn said.

He added that Epstein provided less than two percent of the total funding for the show, Closer to Truth, and that Epstein was only involved with one of its projects, for which he paid less than half of what he had committed. Kuhn said that after learning of Epstein’s arrest in 2019, he used the money he did receive from Epstein for “general overheads in order that none of his money funded even that one project.”

Asked why he continued to associate with Epstein amid mounting allegations, including an explosive 2018 article in the Miami Herald that revealed Epstein had abused dozens of underage girls, Kuhn said “it’s a legitimate question.”

He said he was focused on raising money for his TV show and impressed by Epstein’s network of respected scientists and public figures. “Considering all the people he was dealing with, it’s not something that crossed my mind.”

“Epstein’s depraved activities are among the most reprehensible, atrocious, and insidious ways that inflict human harm,” Kuhn said. “It’s the enduring terror of psychological abuse, and the enduring power of money and glitz.”

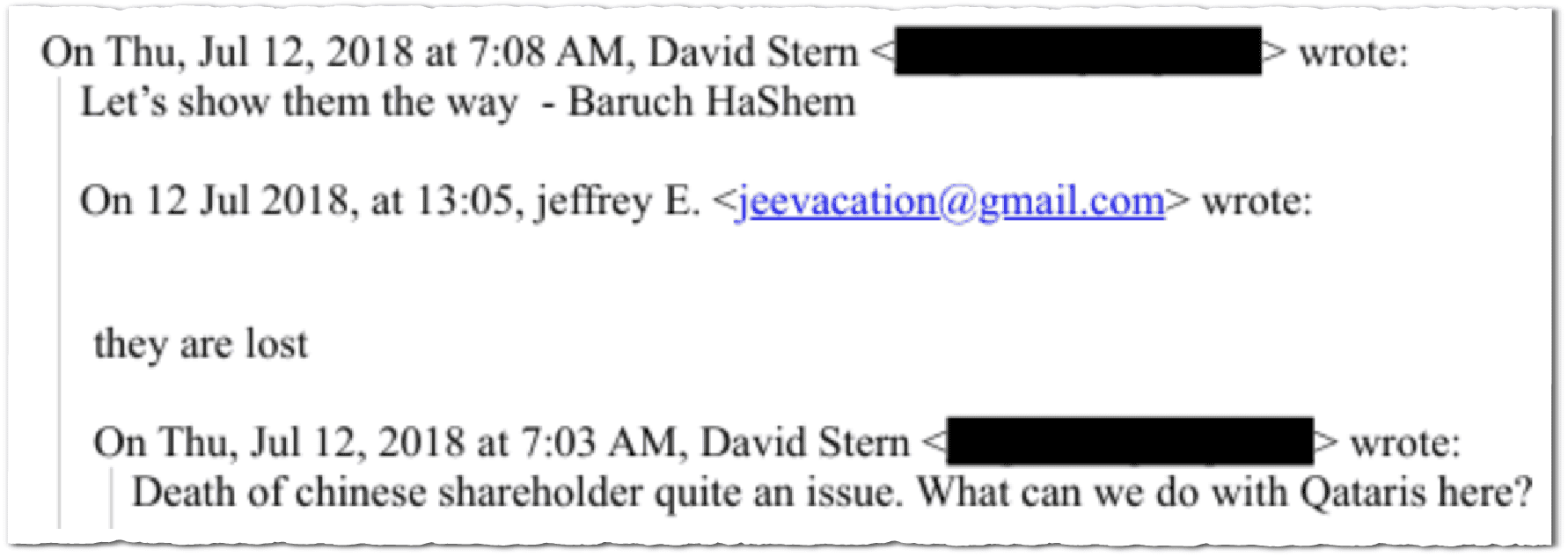

Stern also continued pitching Epstein even as he faced mounting legal troubles in the U.S.. For years, the two men had discussed a bid for Deutsche Bank with the support of Qatar, whose royal family is a minority shareholder in the firm. In July 2018, one week after Wang Jian, the co-founder of Chinese conglomerate and Deutsche Bank stakeholder HNA Group, died in an accident in France, Stern emailed Epstein: “death of Chinese shareholder quite an issue. What can we do with Qataris here?”

“They are lost,” Epstein replied.

“Let’s show them the way,” Stern said.

Nothing ever came of it.

Noah Berman is a staff writer for The Wire based in New York. He previously wrote about economics and technology at the Council on Foreign Relations. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe and PBS News. He graduated from Georgetown University.

Eliot Chen is a Toronto-based staff writer at The Wire. Previously, he was a researcher at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Human Rights Initiative and MacroPolo. @eliotcxchen

Rachel Cheung is a staff writer for The Wire China based in Hong Kong. She previously worked at VICE World News and South China Morning Post, where she won a SOPA Award for Excellence in Arts and Culture Reporting. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Columbia Journalism Review and The Atlantic, among other outlets.