Gary Rieschel, head of Qiming Venture Partners since 2006, stands out as a survivor. While other venture capital firms quit China, Rieschel has endured the country’s sharp downturn in start-up investment, a shift to industrial tech, a crackdown on private enterprise, a split of Silicon Valley-China cross-border deals and a move to state-directed venture capital.

Now he faces another challenge. After building Qiming into one of the larger Sino-U.S. venture players with $9.5 billion in capital under management, in this geopolitically charged climate, Qiming recently trimmed its next flagship China fund from an original $1 billion high point to $600 million.

“Virtually all the Chinese funds are raising smaller funds than they did two or three years ago. And that’s just a reflection of the geopolitical rivalry where a lot of U.S. investors are no longer excited about China because of geopolitics,” Rieschel told me in an interview.

“This is the first real slowdown China has seen since venture capital institutionalized in 2005,” Rieschel added in his deep, booming voice. “The market is not used to anything [other than steady growth] in terms of size of funds and deployment of capital. So everyone feels like this is slowing down. Qiming is still doing 30-plus deals a year, so I view that as slower than the peak, but not at all what I would call slow.”

Venture capital in China has come under pressure after a Silicon Dragon rush of money, talent, startups and deals. For nearly two decades, China’s startup ecosystem thrived on ambitious founders, deep-pocketed investors, tech startups in the mobile internet, e-commerce and fintech, and a relentless drive to compete.

Rieschel started investing in China after working as an executive at Softbank, Cisco and Intel early in his career. That led to Softback Venture Capital and its Softbank Asia Infrastructure Fund, or SAIF. Immersed in China’s bustling VC scene, he helped set up three China VCs, then, in 2005, moved to Shanghai and started Qiming the following year with Duane Kuang, former director of Intel Capital China.

Qiming was on the fast track. The firm invested in more than 580 startups in healthcare and technology, and has played a leading role in China’s evolving venture market. More than 210 of its portfolio companies went public — many in China — or were acquired or merged. As many as 80 became unicorns. Among the firm’s recent hits are the IPOs of robotaxi business WeRide on Nasdaq and the Hong Kong stock exchange, and artificial general intelligence startup Zhipu, also in Hong Kong.

But by 2018, the U.S. was recognizing China’s startling rise in tech innovation and began to regard it as a threat to its leadership. The world’s two superpowers locked horns over conflicts in trade, investment, technologies and resources.

“The West under-estimated the sheer power of China’s capability to take A to A prime, a one to a two to a three. The Chinese are phenomenal at that,” Rieschel related. Now “China will try to become as independent as possible. That includes semiconductors, manufacturing, AI, and biotech”.

As competition increased and U.S. regulations targeted investment in Chinese tech startups, U.S. VCs retreated and China’s venture market nearly collapsed. China VC funds reached only $45.8 billion in 2024 — less than half of previous years — while deals also declined sharply. This was a sharp contrast with the peak in 2018, when China venture spending hit $105 billion, almost at the same level of the U.S. at $118 billion.

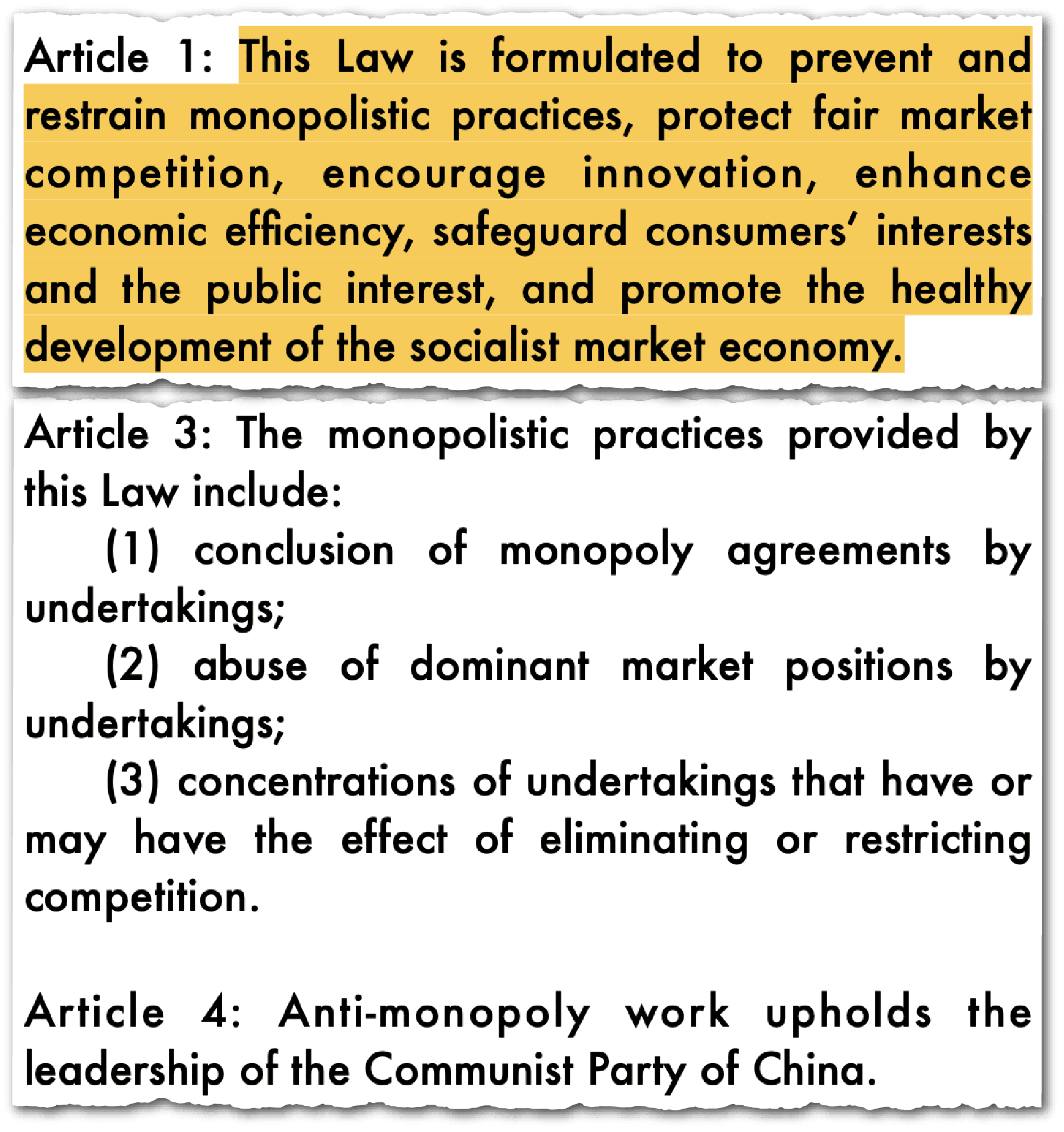

The backdrop was China’s economic slowdown, fewer IPO approvals in Shanghai and Shenzhen, a plunge in cross-border U.S.-China mergers and acquisitions, and a regulatory crackdown on China’s expansive tech titans from 2021 to 2024 that saw Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, Didi and other giants downsize and lose market value. Beijing attacked monopolistic practices, and targeted Jack Ma and other outspoken tech founders. China’s BAT sold off non-core assets, stopped investing in U.S. tech startups, scaled back international expansion and turned inward to their home country — but have recently found new momentum as the crackdown has eased and AI has taken off in China.

BEIJING TAKES CONTROL OF VC

In China’s venture market, meanwhile, the freewheeling, risk-taking culture that had defined the boom of 2005 to 2019 was replaced by the heavy hand of the state. Two-thirds of China’s VC funding today now comes from state-backed entities — governmental funds, provincial banks, and politically connected firms. Under Communist government control, state-backed funds support industrial sectors that align with the country’s ambition to become the world’s dominant tech power. The priorities for the future belong to sectors that can strengthen China’s industrialization: semiconductors, AI, autonomous driving and robotics.

Venture capital, by nature, thrives on risk, speed, and a willingness to fail. But China’s new top-down system demanded predictability, guaranteed returns, and compliance. One veteran venture capitalist — who had backed some of China’s most successful startups — recounted a tense meeting with Chinese government officials in late 2023. “They kept asking: ‘Where are your unicorns [privately held startups valued at over $1 billion]?’” he told me. “I wanted to say, ‘That’s not how this works. Unicorns don’t appear just because you demand them.’”

It wasn’t just about the money. The spirit of China’s venture boom disappeared.

When evaluating potential deals in China, “you had to decide if an investment was being made for political reasons or for commercial reasons,” commented longtime U.S.-Asian investor Stephen Markscheid at Aerion Capital, a family office in Chicago.

Rieschel is one of the few American VCs that continues to tout China tech, and to manage a China-oriented VC firm. The firm has avoided scrutiny in part by having a single investing team located in Shanghai rather than the usual Silicon Valley-China set-up.

More state funding of tech startups is coming. In early 2025, China launched a fund of 1 trillion ($138 billion) to boost AI, quantum computing, robotics and other emerging technologies critical to its economy. That was followed late last year by plans to launch a national $21.4 billion fund for hard tech and early-stage startups, and to set up three regional funds.

As early as 2016, Qiming “started to put more investment in core tech, semiconductor equipment, advanced manufacturing — much more core tech base than two cycles ago”, Rieschel explained, a move that aligned with Beijing’s national priorities for growth.

The earlier go-go period of the mobile internet boom in China sparked a frenzy of dealmaking in consumer tech startups. Apps like WeChat, TikTok (Douyin), and Meituan reshaped everyday life, fueled by venture money that chased fast growth and quick exits. Now that model was dead. The new buzzword was “hard tech”.

“These kinds of deals take a technically oriented entrepreneurial pool. Entrepreneurs from 2009 to 2019 can’t easily pivot to doing real core tech,” noted Rieschel.

“I think that the big change for everyone is that there was a lot of stupid money deployed back in the 2013 to 2020 era in some of the consumer models that wound up wasting a great deal of capital,” he added. “If you had a portfolio that was heavily exposed to that, and you were still deploying capital in the 2016–17 to 2020 timeframe, then you have a lot of work to do on that portfolio.”

With an authoritarian hand taking control of the China venture industry and geopolitics worsening, several VCs relocated to Asian hubs, primarily Singapore. They rarely, if ever, return to mainland China — although they miss the frenzied days of dealmaking in Beijing and Shanghai, when deals were made over WeChat and it could take two hours by taxi from Tsinghua University’s tech center in the capital’s northwestern outskirts to the China World Hotel and other popular meeting points in the city center.

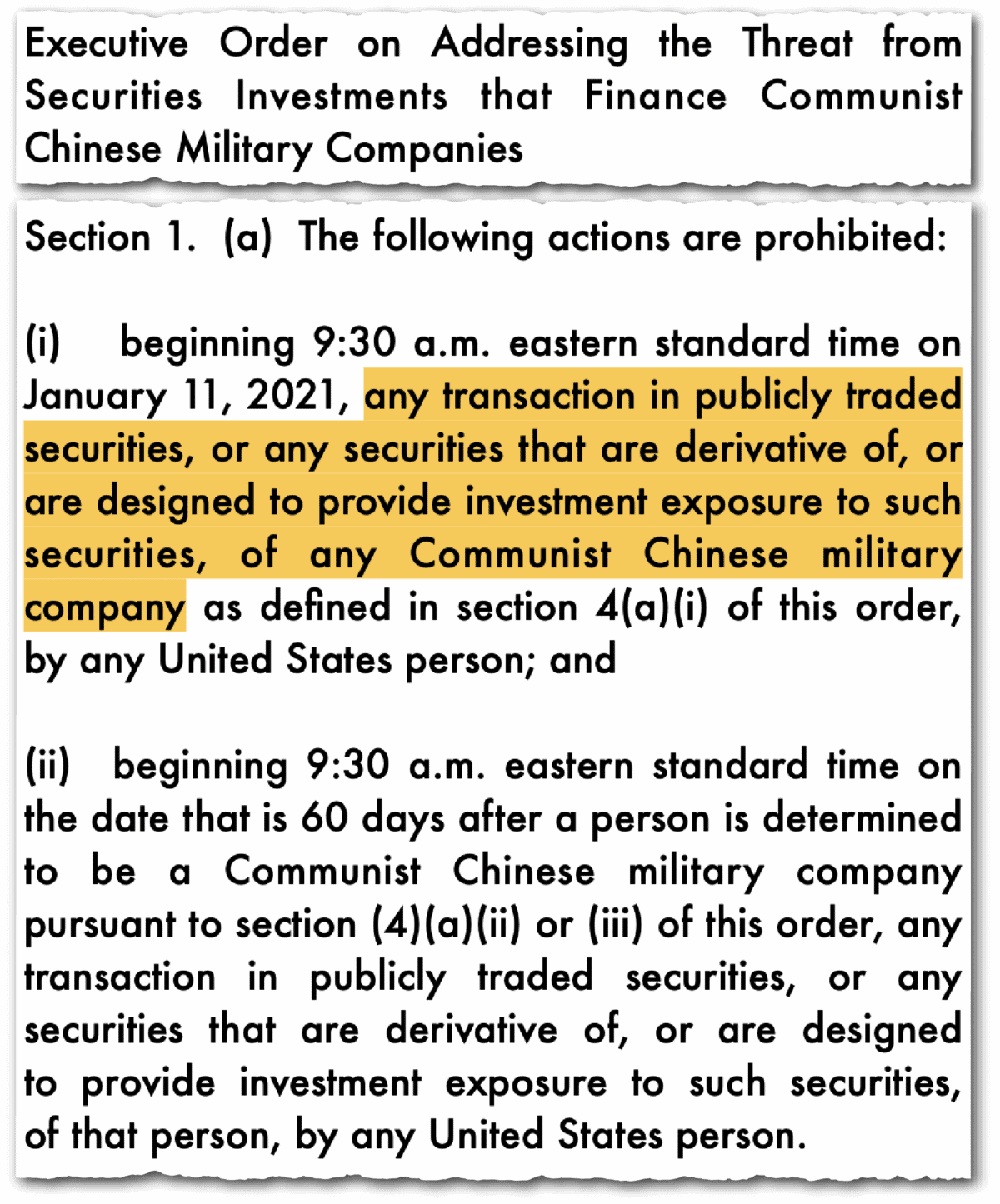

In the tense politicized environment, U.S. venture firms scrambled to offload their Chinese portfolio companies and separate China and U.S. data and funding. U.S. public pension funds and university endowments, which capitalized these U.S.-China VC funds, began to reconsider further allocations and seek assurances that their cash would not go into Chinese companies subject to various U.S. investment restrictions. Qiming’s recent first close on more than half of $600 million for its smaller 9th dollar fund comes from a mix of new and existing investors. Prior limited partners in its funds have included Princeton, Duke, MIT and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

U.S. SCRUTINY AND A TURN TO RENMINBI FUNDS

In 2023, shock waves hit Silicon Valley from Washington. A Congressional investigation prompted by a Georgetown University report targeted five Bay Area firms at the forefront of China tech investment — Sequoia Capital, GGV Capital, GSR Ventures, Walden International and Qualcomm Ventures. Although Sand Hill Road players earned billions from early bets on China’s first wave of emerging companies from 2000 to 2018, now the geopolitical pressure coupled with investment restrictions were too much. They began trying to sell stakes in Chinese portfolio companies such as ByteDance (TikTok’s parent), and they split up China and U.S. operations into two separate units. Sequoia China, one of the world’s top-performing VCs, became HongShan under Neil Shen and began investing separately from a China-focused $9 billion fund raised in 2022. GGV Capital split into Notable Capital for the U.S. and Granite Asia based in Singapore. GSR Ventures also divided into two, renaming its Palo Alto office Informed Ventures.

In this tense environment, many venture partners went silent on anything to do with China, fearing it wasn’t safe to talk, let alone invest. An often-repeated phrase circulated: those who talk don’t know, those who know, don’t talk.

By early 2025, tighter U.S. government regulations went into effect that curbed American VC financing of China companies in artificial intelligence, semiconductors and quantum computing. While U.S. VC firms have not been legally forced to divest from Chinese investments overall, they faced growing political pressure over national security and human rights issues, and restrictions on funding companies whose technologies have potential military applications.

Few U.S.-China venture investors have adapted to these major shifts as easily as Rieschel. He has kept Qiming at a greater remove from political turmoil during his two-decade stewardship.

The Chinese government has continued to be conflicted in terms of real risk appetite… They don’t want to lose any money so they’re partnering with firms like Qiming and HongShan to manage funds on their behalf. They’re trying to leverage some of the expertise the funds have.

Gary Rieschel

Of the pioneering U.S.-linked VC firms investing in China, Qiming is the rare one that has stayed the course. It has raised 8 U.S. dollar funds focused on China and seven RMB funds. Rieschel is one of the few American VCs that continues to tout China tech, and to manage a China-oriented VC firm. The firm has avoided scrutiny in part by having a single investing team located in Shanghai rather than the usual Silicon Valley-China set-up.

Its winning bets include food delivery app Meituan and smartphone maker Xiaomi, deals made around 2000. Rieschel, who has tracked Xiaomi and its well-known founder Lei Jun from the start, credits Xiaomi for innovating across technology platforms to get into electric vehicles while Apple couldn’t make a similar leap into EVs.

The firm’s misses include facial recognition startup Megvii, which failed to go public despite several attempts and was blacklisted by the U.S. government in 2019 for alleged human rights violations, a move that restricted its access to U.S. technology and investment.

Qiming has avoided closer scrutiny by investing heavily in biotech, rather than more sensitive sectors. The firm’s healthcare tech investments, such as in coronavirus vaccine maker CanSio and drug developer Zai Lab, have paid off. “China has made great progress over the past decade in building out an innovative biotech and pharma ecosystem,” says Rieschel.“The Pfizer’s and Lilly’s have multiple teams of people scouring China for opportunities to license Chinese healthcare and biotechnology, and bring it to the U.S. That’s a big trend.”

Number of Unicorns by Top Ten Global Cities (2024)

| San Francisco | 190 |

| New York | 133 |

| Beijing | 78 |

| Shanghai | 65 |

| London | 45 |

| Shenzhen | 34 |

| Bangalore | 32 |

| Paris | 25 |

| Guangzhou | 24 |

| Hangzhou | 24 |

Hurun Report, CVinfo, Gobi Partners

But biotech investing carries risk too. “The likelihood of U.S. investment restrictions on Chinese biotech companies is a maybe,” he adds. “The Chinese ecosystem is now at critical mass, so U.S. government controls will not do much to slow down Chinese development.”

Rieschel recognized early that China tech investing was becoming more Chinese and nationalistic. His firm raised several renminbi-denominated funds to invest in homegrown Chinese startups and take them public in Shanghai, Shenzhen or Hong Kong. Qiming completed its seventh fund at RMB 6.5 billion ($900 million) in 2023, and it’s raising an eighth RMB fund of about the same size.

“Over 90 percent of the venture capital money now being deployed in China is in renminbi. If you’re managing dollar funds as your only source of capital, you’re not participating in a lot of the deals that are getting done,” said Rieschel.

“What’s happening now is that the renminbi money has adopted a higher-risk profile than it had 20 years ago. It’s more willing to go into earlier stage tech companies. The first renminbi funds wanted nothing to do with hard-core technology risk. The Chinese government has continued to be conflicted in terms of real risk appetite in a lot of ventures. They don’t want to lose any money so they’re partnering with firms like Qiming and HongShan to manage funds on their behalf. They’re trying to leverage some of the expertise the funds have.”

China’s hybrid funds, which combine private capital with state industrial objectives, have become dominant, prioritizing investment in emerging technologies such as quantum computing, AI, robotics, and high-end chips.

But the Chinese government’s results have been mixed. “If you look at semiconductors, they just blew up about $500 billion. It has not been a glorious outcome of innovation investment, at least in semiconductors.” He was referring to several government-subsidized, multibillion-dollar chip foundries that failed in China after corruption scandals in 2020-2022, and as Rieschel put it, “the sheer capital intensity in building chips.”

FROM SHANGHAI TO SEATTLE AND MONTANA

Rieschel directed Qiming from Shanghai for 11 years (rather than parachuting like most Sand Hill Road investors), working from the firm’s offices at the Jin Mao Tower in Pudong overlooking the Huangpu River and The Bund.

In 2016, well before the downturn, Rieschel and his wife moved back to the U.S. and settled in Seattle. The following year, Rieschel launched the firm’s first U.S.-focused fund, Qiming US, which has raised $550 million across three funds and invested in 30 healthcare technology companies, leading to 11 M&A deals and IPOs. It’s a post that allows him to apply his biology degree from Portlan, Oregon-based Reed College (Reed’s claims to fame include its most successful drop-out, Steve Jobs).

Meanwhile, Qiming has been undergoing a generational transition. Some of its highest-returning venture investors have moved on: in 2013, Hans Tung joined GGV Capital (rebranded and repositioned as Notable Capital), where he sealed a deal with Musical.ly that paved the way for TikTok’s global expansion; JP Gan exited in 2019 to form his own fund INCE Capital; Nisa Leung, who oversaw the firm’s healthcare investments, departed last year for her newly formed Aulis Capital.

For Qiming and other firms that were pioneers in China tech investing, the best days were great and may not be over yet, but success in China is more uncertain and challenging than ever.

After taking a bet that China venture investing would pay off and returning to the states nearly ten years ago now, Rieschel has become an industry spokesman. He still travels to China at least twice a year, chairs the Asia Society Northern California/Seattle chapter, and co-chairs the Atlantic Council’s China hub. He’s also found time to enjoy his private wine collection, fly-fishing expeditions and a Montana home.

For Qiming and other firms that were pioneers in China tech investing, the best days were great and may not be over yet, but success in China is more uncertain and challenging than ever.

Adapted from The New Tech Titans of China: Innovation Under Pressure in the World’s Most Ambitious Economy, launching February 24, 2026.

Rebecca is an internationally recognized expert on tech innovation, venture capital, and U.S.-China geopolitics. She is a journalist, public speaker, and author of five books including Silicon Dragon and Tech Titans of China. She has contributed to CNBC, Newsweek, Harvard Business Review and others.