China’s economy may still be on course to meet the government’s growth target this year, but a look behind the headline figures illustrates just how ‘two-speed’ in nature that growth has become.

The country recorded overall third quarter GDP growth of 4.8 percent year-on-year in the third quarter, meaning it should still expand by around 5 percent in 2025 — in line with the leadership’s aims.

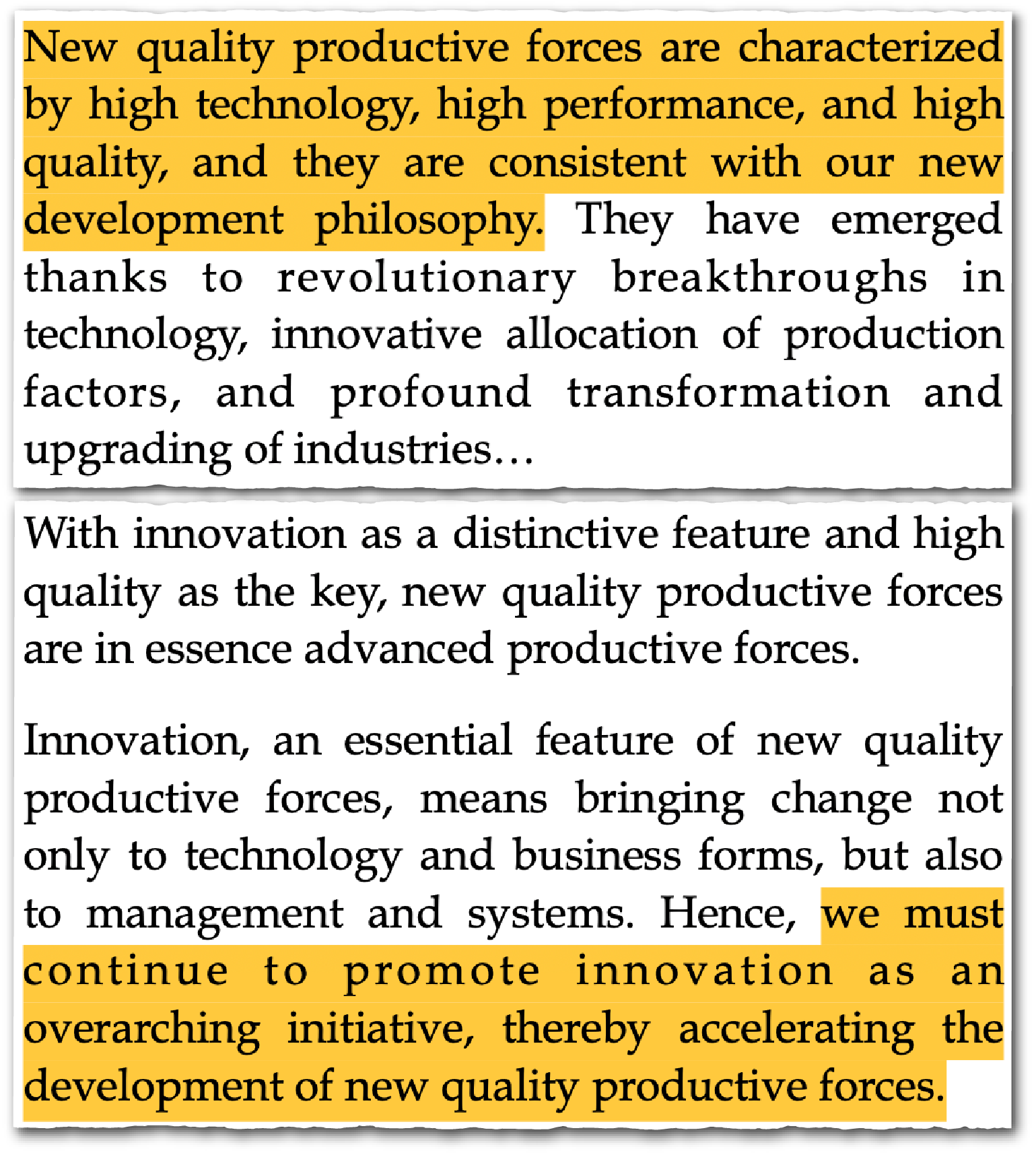

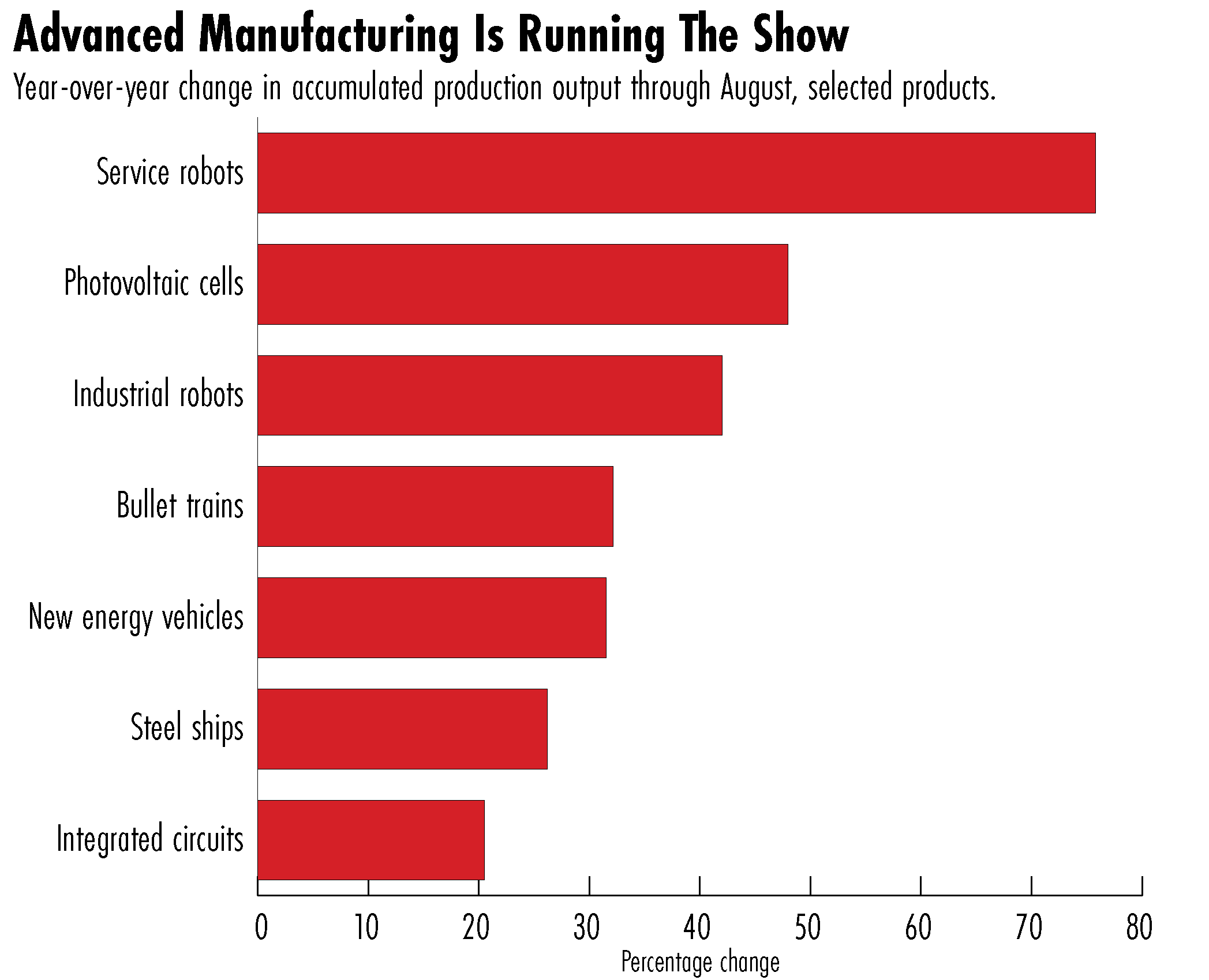

The breakdown provided by the Chinese statistics bureau this week shows that industries that are part of what Chinese leader Xi Jinping refers to as China’s “new productive forces” are still steaming ahead — sectors related to tech and clean energy, which Xi hopes will power China’s economy for years to come. Output of photovoltaic cells used in solar panels, industrial robots and electric vehicles all grew by over 30 percent year-on-year through August for example.

“The CCP is clearly prioritizing the high-tech economy, particularly the hard-tech side of it,” says Gerard DiPippo, associate director of the RAND China Research Center. “Part of this is related to the self-reliance campaign, but it’s also just Xi’s vision of what techno-industrial growth looks like.”

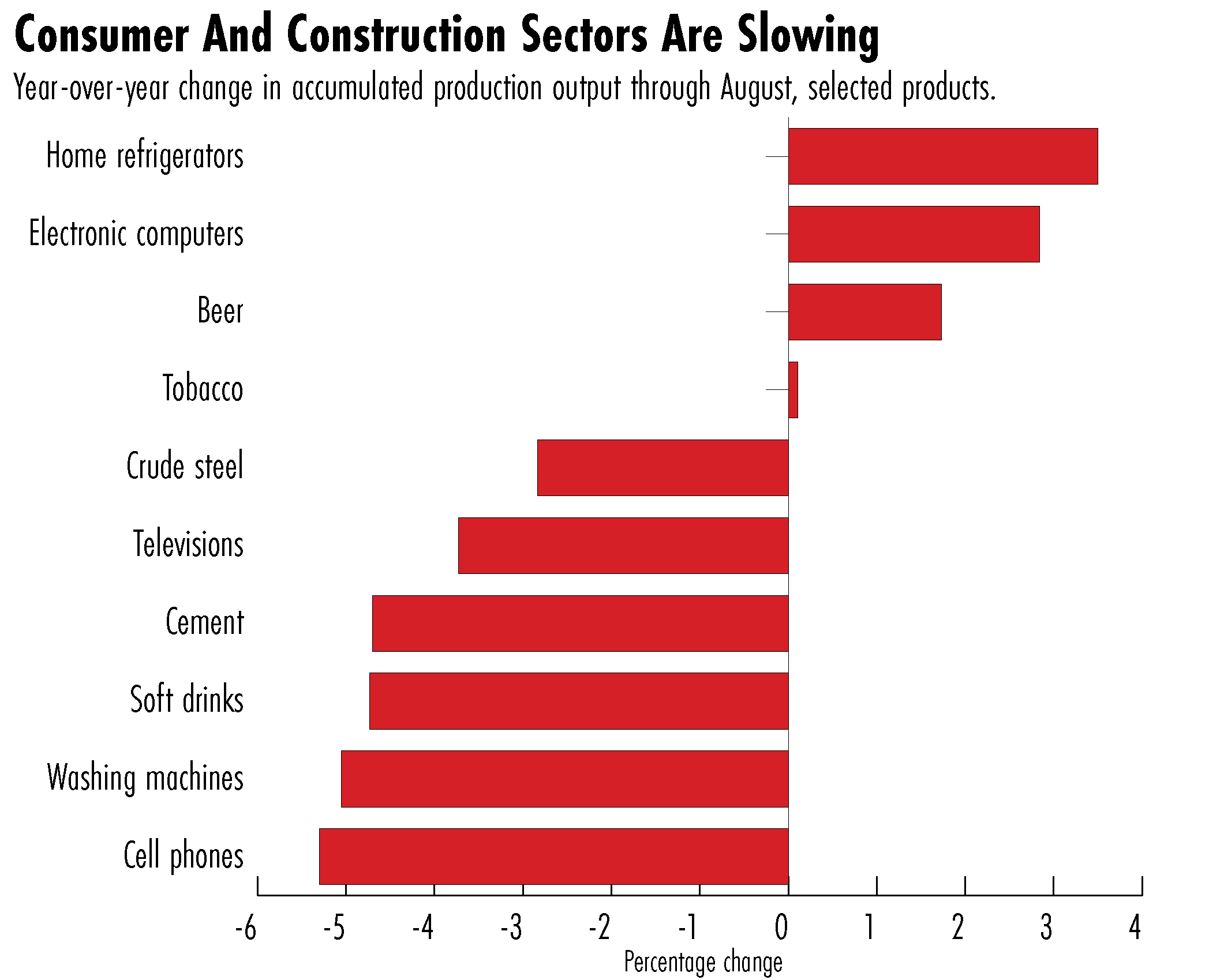

Meanwhile, sectors more associated with domestic consumer spending and the country’s under-pressure property sector have grown sluggishly, if at all, so far this year.

“The economic engine is still resiliently chugging along, but households are cautious and private firms are hesitant,” says Lizzi Lee, a fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute. “The danger is that this multi-track pattern hardens, with policy and credit keeping the supply side afloat while demand keeps falling behind.”

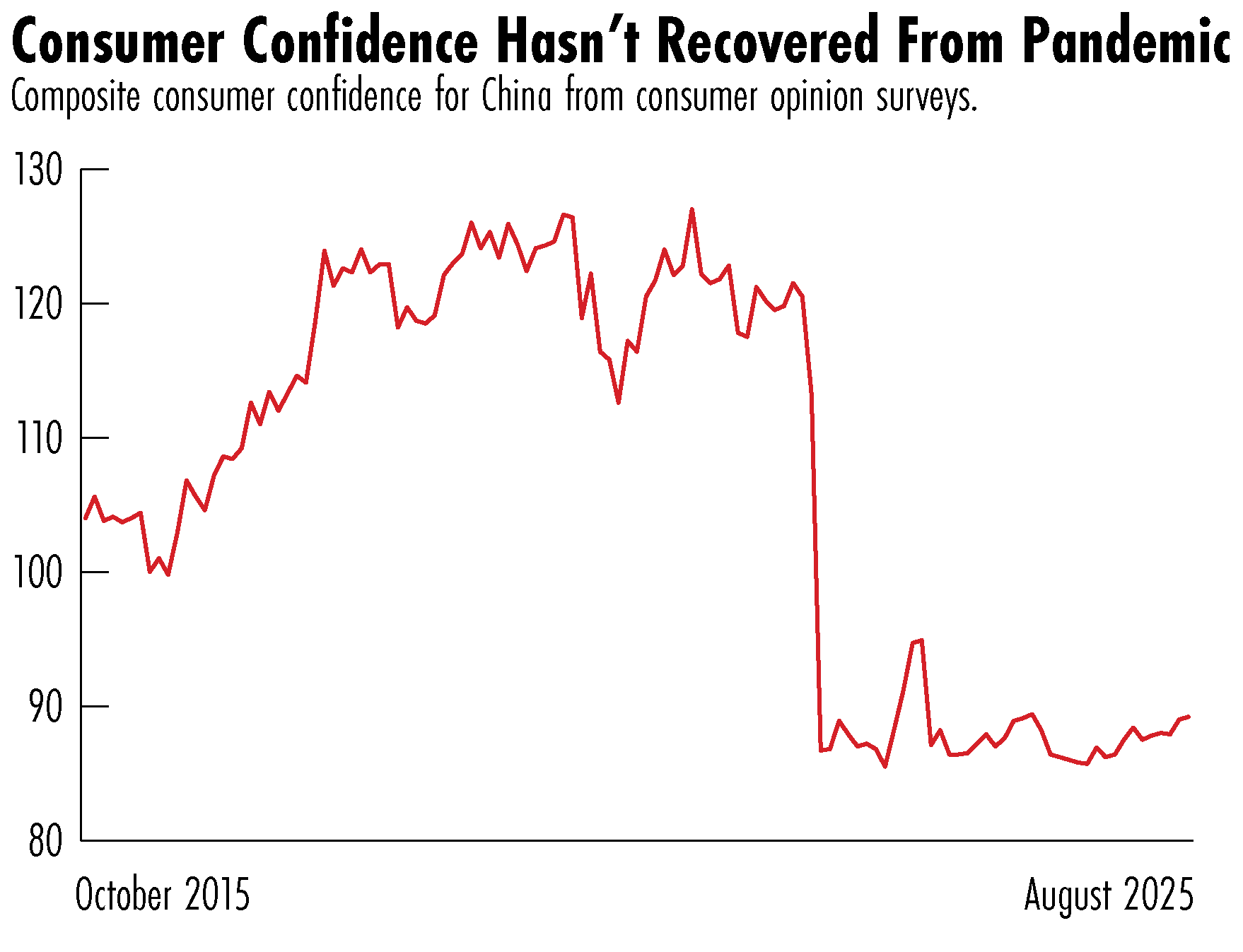

Chinese consumers have been hurting since April 2022, when China ordered Shanghai and other megacities to lock down as part of its response to the Covid pandemic. Consumer confidence plummeted and remains in the relative dumps.

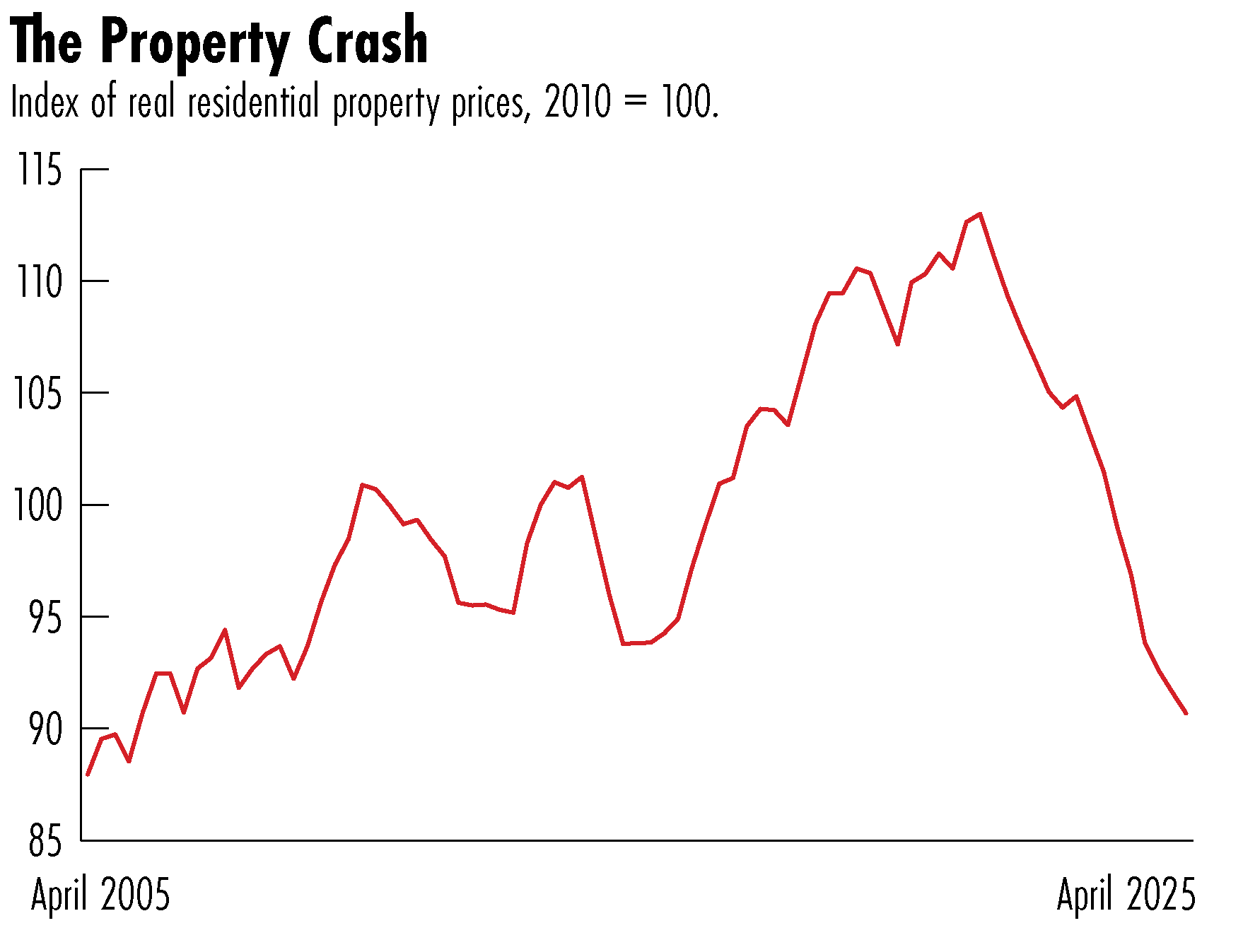

One reason is an ongoing property crisis. Real estate investment in August was a third-lower than it was the same month in 2023. An inflation-adjusted index of home prices fell to a 19-year low in the second quarter.

[China] risks being caught in a loop of producing more and innovating more, but with the gains not shared broadly at home, which would eventually sap the economy of its innovative energy.

Lizzi Lee, a fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute

“The property sector is the thing that is the most clearly weighing on aggregate internal demand, and also probably the thing that’s weighing the most on consumer sentiment,” DiPippo says. “In essence, [the decline is] deflating everyone’s savings.”

China has kept its economy humming by selling goods abroad. In 2024 it recorded a record $1 trillion trade surplus and is on track to surpass even that figure this year. The U.S. remains its top export market, even though shipments there have fallen 17 percent year-over-year in the face of lofty tariffs.

Other markets have helped China fill the U.S.-sized gap. Exports to Africa are up more than 28 percent through September, and exports to Southeast Asia are up 15 percent.

The combination of exports and high-tech manufacturing has delivered China’s economy a boost, but it is not the perfect solution to tackle deeper structural problems, Lee says.

“You can’t rely on factories and tech alone when large parts of the population, especially young people, are not gainfully employed, consumers are saving rather than spending, and many firms outside tech are struggling,” she says. China “risks being caught in a loop of producing more and innovating more, but with the gains not shared broadly at home, which would eventually sap the economy of its innovative energy.”

Noah Berman is a staff writer for The Wire based in New York. He previously wrote about economics and technology at the Council on Foreign Relations. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe and PBS News. He graduated from Georgetown University.