The United States has spent years putting up roadblocks for Chinese vehicles. Could it soon clear the path?

“Let China come in,” President Trump said about the prospect of Chinese cars entering the American market, at a speech in Detroit last month. “If they want to come in and build the plant and hire you and hire your friends and your neighbors, that’s great.”

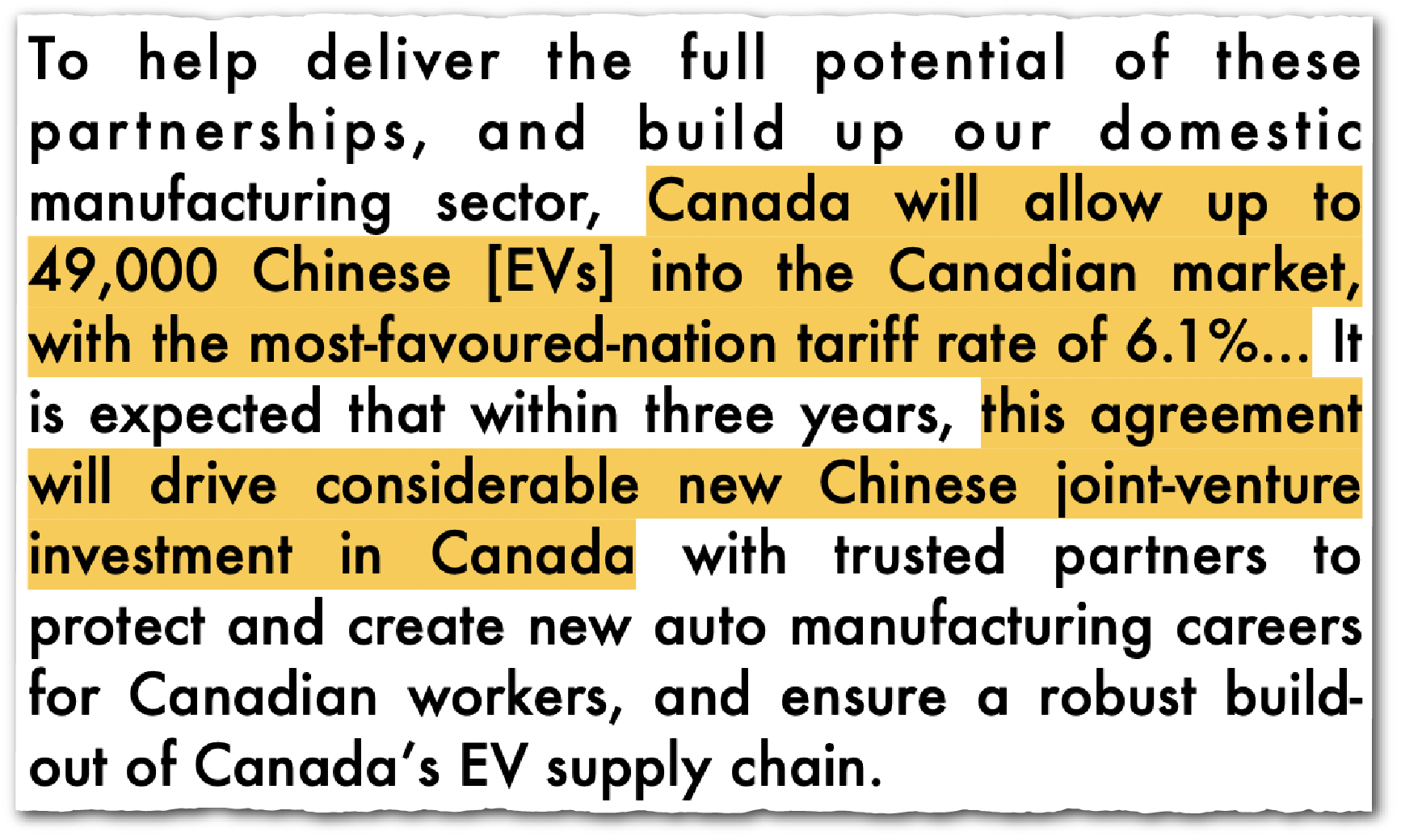

America’s neighbors — and partners in its most important trade alliance — are already opening up to China. Days after Trump spoke, Canada signed a deal with China to drop tariffs from 100 to just 6 percent for an initial set of imports of 49,000 Chinese electric vehicles, which are also gaining market share in Mexico at a rapid clip.

At least one Chinese firm has signaled its interest. Hangzhou-based Geely, China’s number-two carmaker by sales, would consider entering the U.S. market after 2030, a spokesman told The Wire. More than three quarters of U.S. auto executives believe Chinese companies will eventually enter the United States, according to a survey last year by Kerrigan Advisors, a consultant to dealerships.

“It’ll take negotiations between the Chinese government, Chinese manufacturers, and the U.S. government to get there,” says Sam Fiorani, a vice president at advisory firm AutoForecast Solutions. “But it will happen because it will mean American jobs, it will mean providing a product that Americans want to buy, and it will mean increased competition, which is the only way to bring prices down on vehicles.”

Those roadblocks could yet prove hard to budge, however. The U.S. government would have to lower the market barriers it has erected, while allaying concerns about the technology embedded in Chinese EVs and the challenge they could offer to domestic car companies and their employees.

“This is a topic of intense political and policy debate,” says Peter Harrell, a trade expert who was on the National Security Council during the Biden administration — adding that where Trump himself lands will be vital.

“These are all things the executive branch has complete or a big degree of discretion over,” he says. “If Donald Trump wants to let Chinese car companies come into the United States, Donald Trump absolutely will be able to ensure that there are no legal or regulatory impediments.”

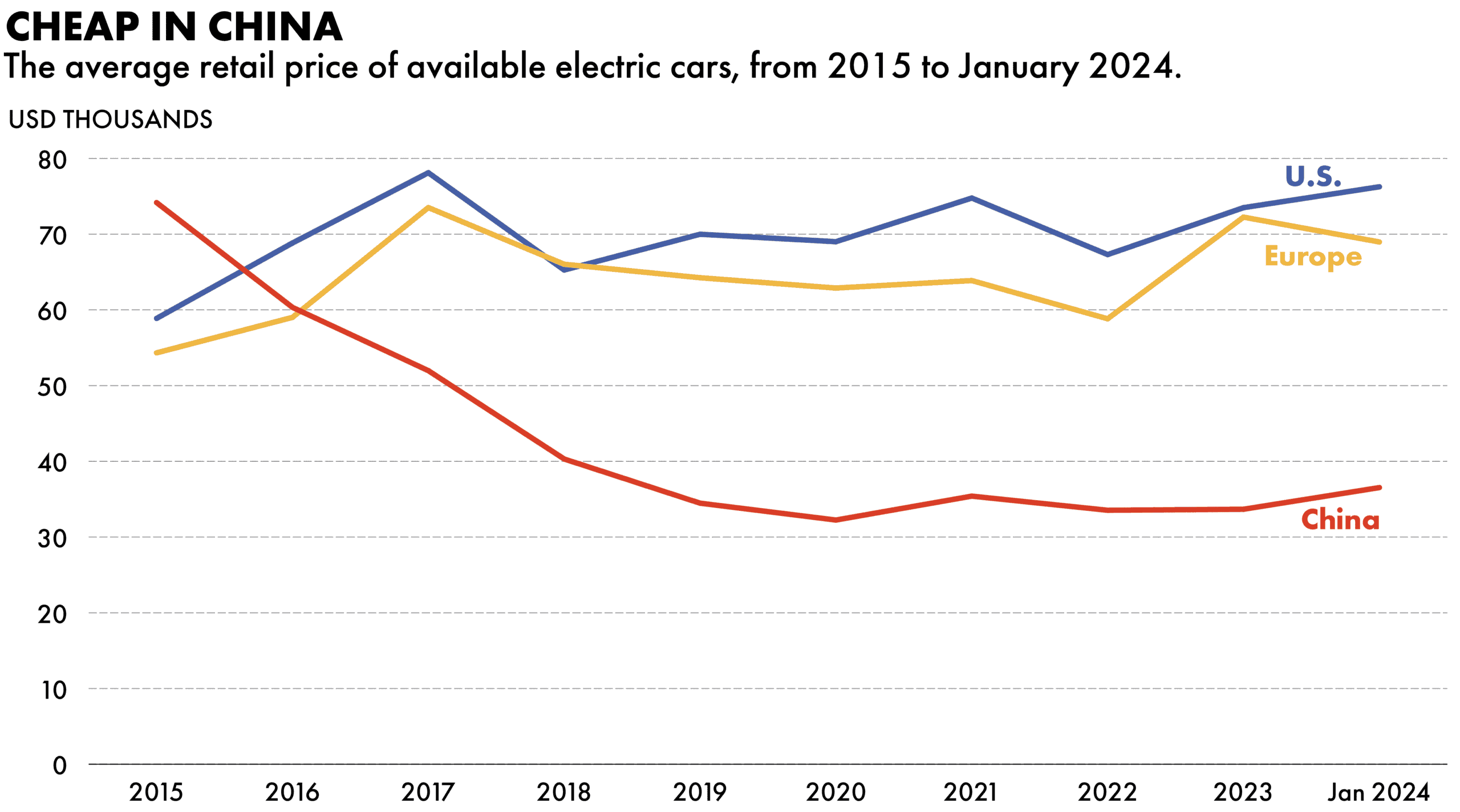

Even without access to the U.S. market, China was able to become the world’s leading auto exporter in 2023, while BYD last year topped Tesla to become the global leader in electric vehicle sales. Many experts view Chinese EVs as being at the cutting-edge of the industry, and affordable to boot: If Chinese carmakers could sell vehicles as cheaply in the U.S. as they do in China, buyers would likely be interested, says Tu Le, founder of consultancy Sino Auto Insights.

“There’s the promise of having a cooler car at a cheaper price,” he says. “Young people aren’t thinking about software restrictions and hardware restrictions.”

Do we really want to give the CCP one more leverage point to be able to switch on and off our critical infrastructure when they’ve already shown the intent and capability to do so?

Liza Tobin, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security

Right now, though, the U.S. has significant limits on Chinese auto firms. The Biden administration placed an effective ban on Chinese EVs in 2024 by imposing a 100 percent tariff on imports, while the Trump administration has introduced additional levies on all imported autos, and on China more broadly. Manufacturers must also comply with Commerce Department rules that ban Chinese-made software in cars that connect to the internet.

One way Chinese firms could navigate the hurdles to market entry is by forming partnerships with companies that already manufacture in the United States — just as Beijing itself has for years made foreign carmakers entering the Chinese market form joint ventures with local, often state-owned firms.

Forcing Chinese companies to partner up would be like “taking a page from China’s own playbook,” says Michael Dunne, a consultant and former General Motors executive. “The Chinese will have nothing to say except, well, okay, you got us.”

The U.S. has a history of getting foreign carmakers to produce in America. The federal government threatened to impose heavy tariffs and quotas on Japanese carmakers after they rapidly gained market share during the 1970s. Eventually the likes of Honda and Toyota set up factories in America, many of which remain in operation.

Still, Chinese auto makers setting up plants in America would create another level of controversy. While the likes of Trump see the potential for job creation, others fear the effect on America’s domestic players.

“If you have below market cost Chinese companies coming in, they are going to do to American companies what they have done in so many other markets,” says Michael Sobolik, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank. “They are going to undercut on price and drive American companies out of business…that would be a potential extinction level event for them.”

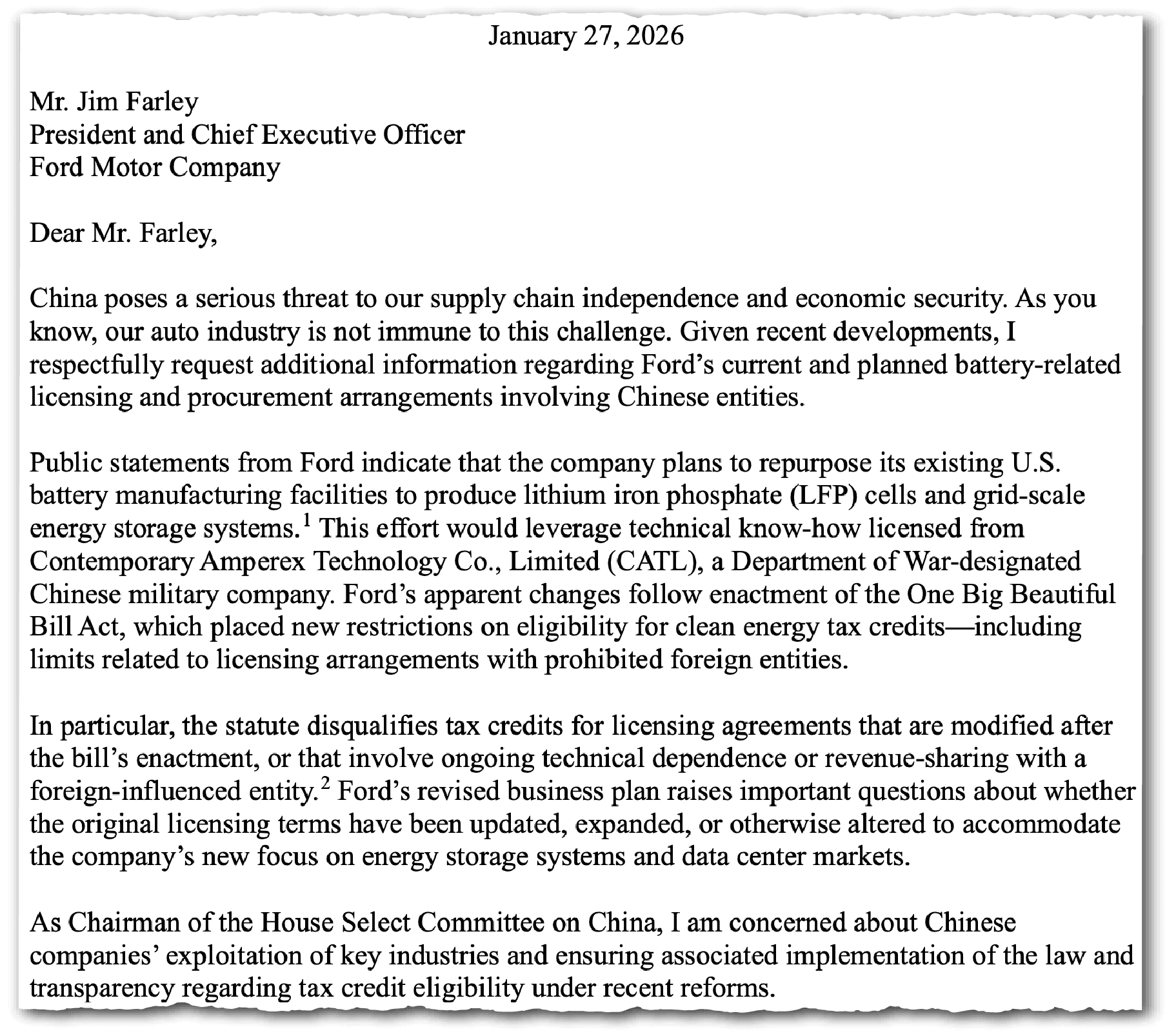

On Tuesday, Republican Congressman John Moolenaar, the chairman of the House of Representatives’s China Select Committee, sent a letter to Ford demanding information on its partnership with Chinese battery giant CATL, arguing that “China poses a serious threat to our supply chain independence and economic security.”

Geely is currently the only Chinese carmaker with a significant toehold in the U.S., via its ownership of Swedish brands Polestar and Volvo, which has a manufacturing facility in South Carolina. Waymo, the autonomous vehicle firm owned by Google parent Alphabet, is building its cars using hardware from Zeekr, another Geely brand.

Whether more American companies will partner with Chinese rivals is unclear, although such tie-ups could offer U.S. automakers a way to compete better internationally, says Sam Abuelsamid, vice president of market research at advisory firm Telemetry. He warns of an “increasingly isolated U.S. auto industry, because they’re producing vehicles they can’t sell anywhere else.”

General Motors, the biggest U.S. automaker by sales volume, has seen its global market share fall from 11.2 percent in 2015 to 6.8 percent last year, according to its annual reports. The U.S. now makes up more than four-fifths of the firm’s revenue, compared to two-thirds a decade ago.

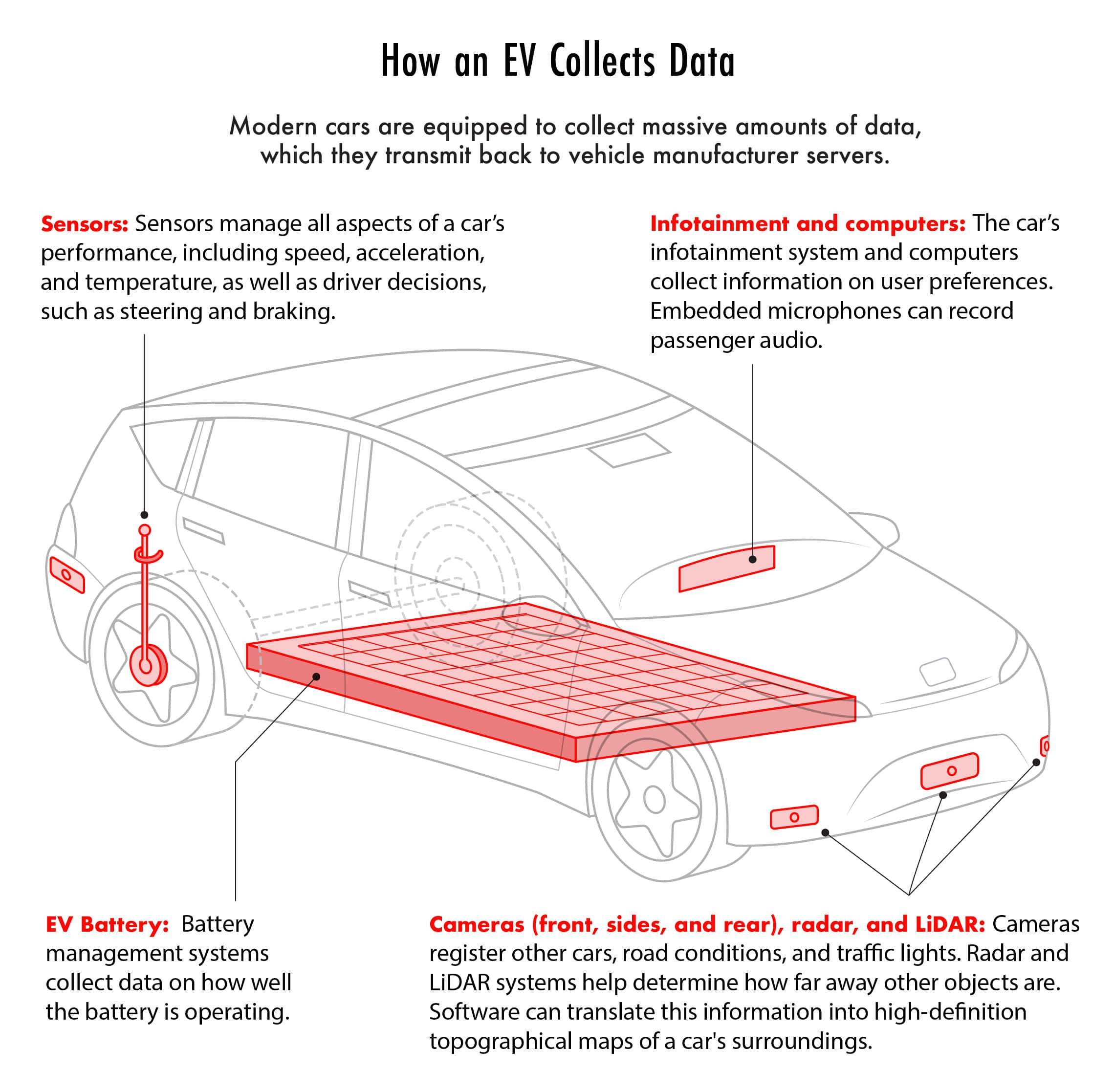

Besides fears around American firms, the potential national security threat posed by Chinese technology has created bipartisan concern. EVs contain cameras and sensors that can record a car’s surroundings, while their systems are increasingly accessible remotely.

“Do we really want to give the CCP one more leverage point to be able to switch on and off our critical infrastructure when they’ve already shown the intent and capability to do so?” says Liza Tobin, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, a Washington think tank.

In January 2025, the Biden administration passed rules set to take effect this autumn that will restrict Chinese companies from selling so-called connected vehicles in the United States. Officials cited fears about Chinese firms collecting U.S. citizens’ data and being able to access vehicles remotely.

The Chinese automakers have been preparing and are poised to jump at the opportunity to get into the United States. It’s still the most highly profitable market in which to sell and service cars, by far…

Michael Dunne, a consultant and former General Motors executive

“The rules don’t categorically prohibit Chinese companies from complying,” says a former Commerce Department official who was not authorized to speak publicly, but “it’s not plausible that Chinese manufacturers would make the necessary investments to comply without some assurances from the administration.”

During Trump’s second term, the U.S. government has signaled somewhat less concern about Chinese technology threats than members of Congress across the aisle. Last week, the Commerce Department pushed out two officials at the office that designed the connected vehicles restrictions, the Wall Street Journal reported.

The department’s Bureau of Industry and Security, which houses the office, did not respond to a request for comment.

A White House official said there had been no change in policy toward Chinese vehicles, adding that “the president is always welcoming of investments that create jobs for American workers, but the president will not sacrifice our national and economic security.”

Another fundamental issue for Chinese carmakers is how open American consumers are to their products. EV adoption is growing in the United States but still trails global levels. EVs made up 8.9 percent of new car sales in the U.S. during the first half of 2025, compared to 23.2 percent in Europe and 47.3 percent in China, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation, a research group. Moreover, the Trump administration last year scrapped subsidies that had made EVs — which cost an average of more than $57,000 in the U.S., according to Kelly Blue Book estimates — more affordable.

EV infrastructure is also not as widespread in the United States as in other markets, though the number of U.S. charging stations grew 19 percent between June 2024 and June 2025, according to an analysis by SBD Automotive and mapping firm HERE Technologies.

For Chinese companies, such challenges may only raise the appeal of the American market.

“The Chinese automakers have been preparing and are poised to jump at the opportunity to get into the United States,” says Dunne, the consultant. “It’s still the most highly profitable market in which to sell and service cars, by far, and so it’s extremely valuable for Chinese automakers to get access.”

Noah Berman is a staff writer for The Wire based in New York. He previously wrote about economics and technology at the Council on Foreign Relations. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe and PBS News. He graduated from Georgetown University.