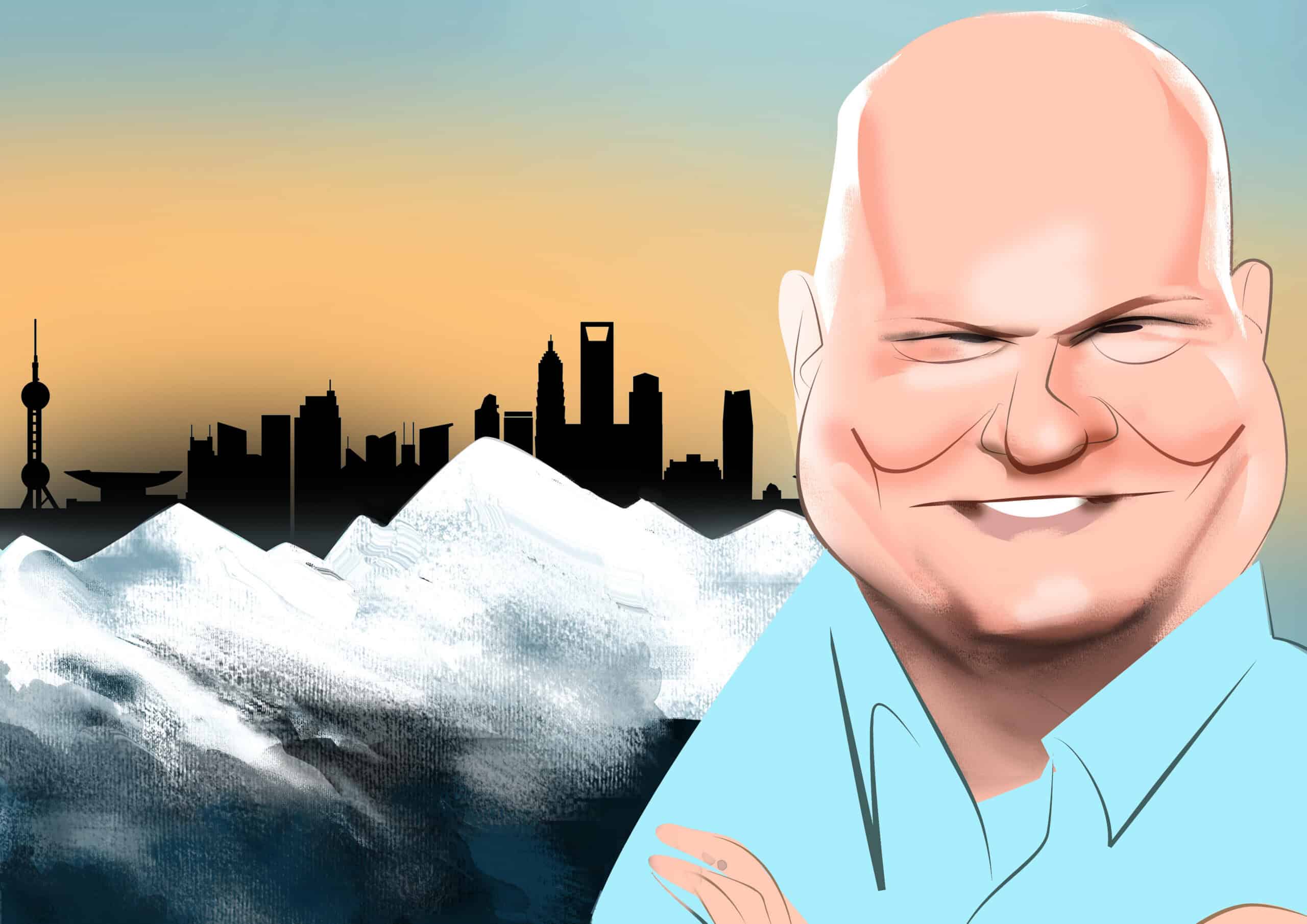

Ma Jun is currently the president of Institute of Finance and Sustainability, a Beijing-based think tank specialized in green finance and sustainability. He was formally a successful financial market economist who in the last decade has turned himself into a leading voice in green finance. Having worked for many years at Deutsche Bank as their chief China economist, he joined the Chinese central bank as chief economist in 2014 and began to advocate green financial policy initiatives in China and globally, including via co-chairing the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group.

We spoke on the sidelines of the New York event regarding the China-U.S. Track II Dialogue on Climate Finance and Trade, which he co-chaired, on a range of other topics including green transition in China and its trade tensions with the United States. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Illustration by Lauren Crow

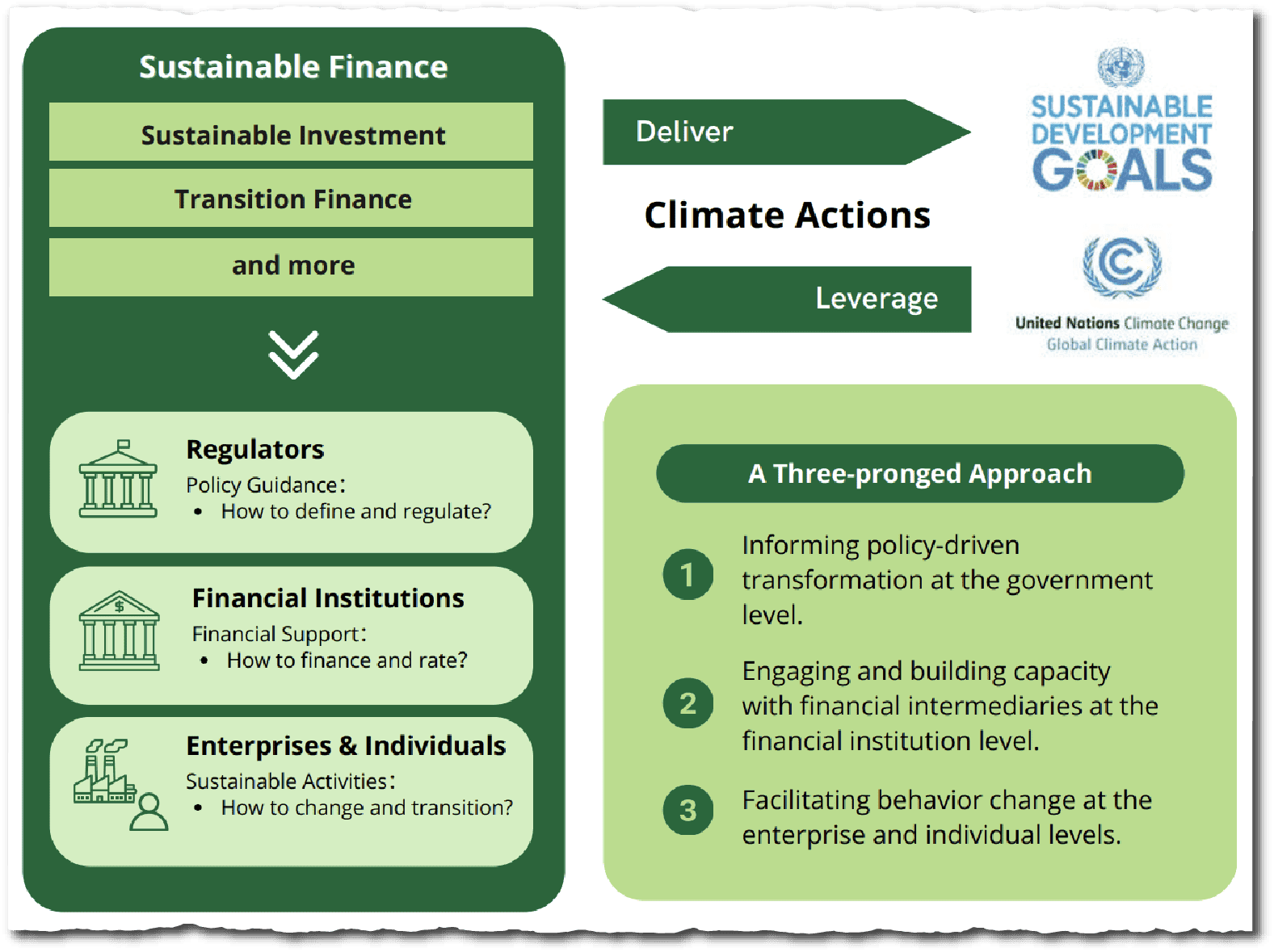

Q: Why is having a green financial system so important for China and what is the biggest challenge in implementing it?

A: To put it simply, because pollution control and climate mitigation require a lot of capital, and the government alone cannot raise the required funds: 90 percent will have to come from the private sector. Private sector funds rely on financial markets, which in turn require a systematic design to define what constitutes green financial activities, and also require financing entities to provide green or sustainability-related information disclosure.

There must also be a suitable set of financial instruments and corresponding policy support to stimulate private sector participation in these green investments. Therefore, a comprehensive institutional design is needed to effectively attract large-scale private sector participation — including clear taxonomies, mandatory disclosures, and standardized verification mechanisms.

Can transition finance really prosper?

Let me give you an example. I recently participated in a People’s Bank of China conference on transition finance for the steel industry in Hebei Province. The aim was to connect financial institutions with enterprises and to promote the concept of transition finance for the steel industry, one of the largest hard-to-abate sectors in China.

| BIO AT A GLANCE | |

|---|---|

| AGE | 61 |

| BIRTHPLACE | Shanghai, China |

| CURRENT POSITION | President of Beijing-based Institute of Finance and Sustainability (IFS) |

At the meeting, I heard that banks in Hebei had already provided more than 10 billion yuan ($1.39 billion) in transition finance to steel companies in just a few months. But they now estimate that more than 100 billion yuan ($13.9 billion) in transition finance will be needed for steel companies in the province. So transition finance in this sector may increase tenfold.

Many other hard-to-abate sectors, such as cement, chemicals, non-ferrous metals, textiles, paper, aviation, shipping, etc., are also the target clients of transition finance. If the whole country starts to move in that direction, driven by policy frameworks and market demand, the potential for the transition finance growth is huge.

Many steel plants in China have already closed due to insufficient domestic demand. Won’t the green transformation put even more pressure on them?

Some Chinese companies in steel and cement are being closed, mainly due to shrinking demand in the real estate and construction industry. For example, housing sales have dropped by half from the peak, and so has the demand for construction steel.

But the remaining companies must transform. If they don’t, they will also close. Why? Because in the future the whole country will have to achieve carbon neutrality, and all steel and cement production must become zero-carbon. If they can’t achieve zero-carbon, there will be no buyers for them — whether due to regulatory requirements, international trade standards, or shifting consumer preferences toward low-carbon products.

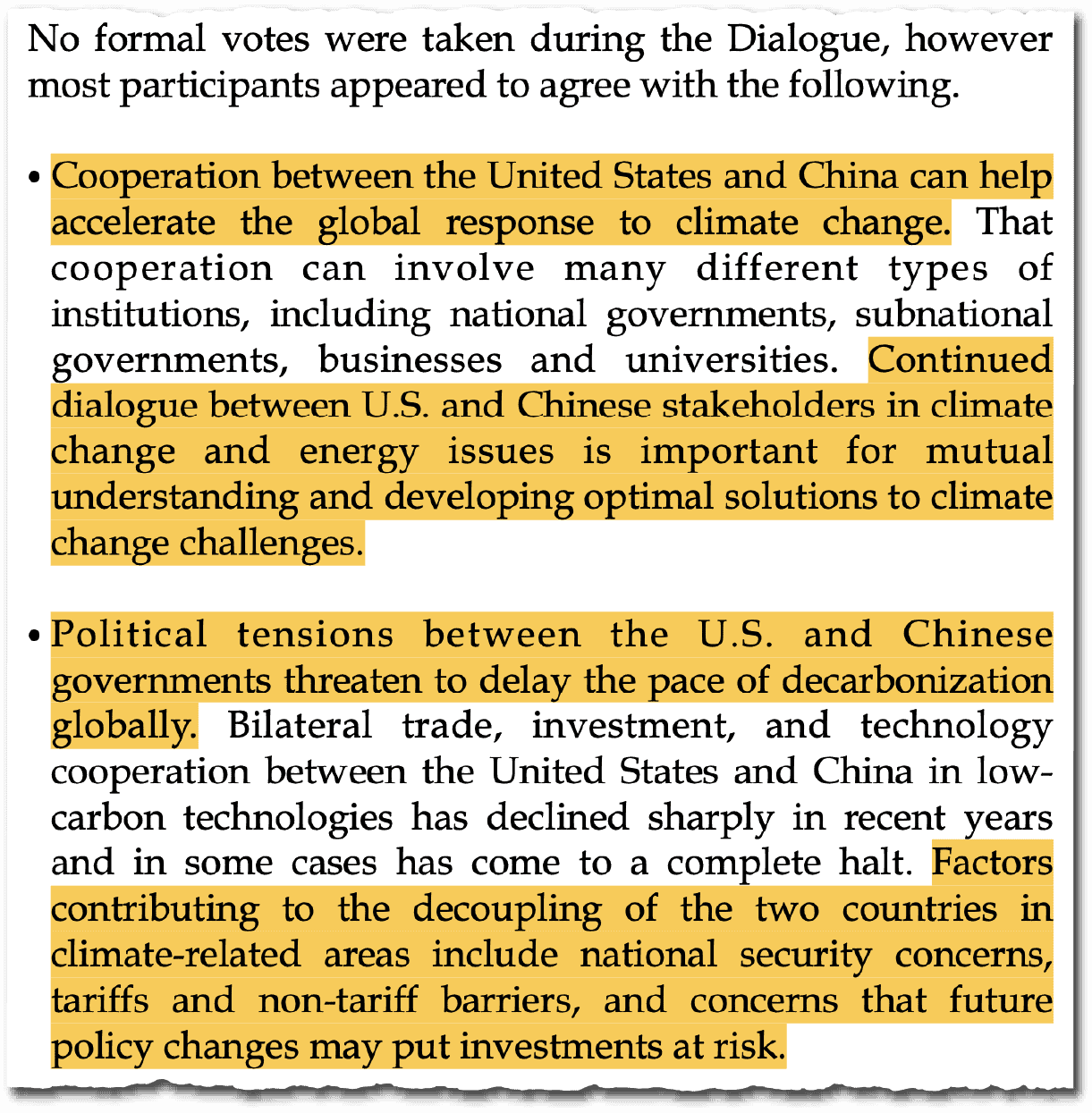

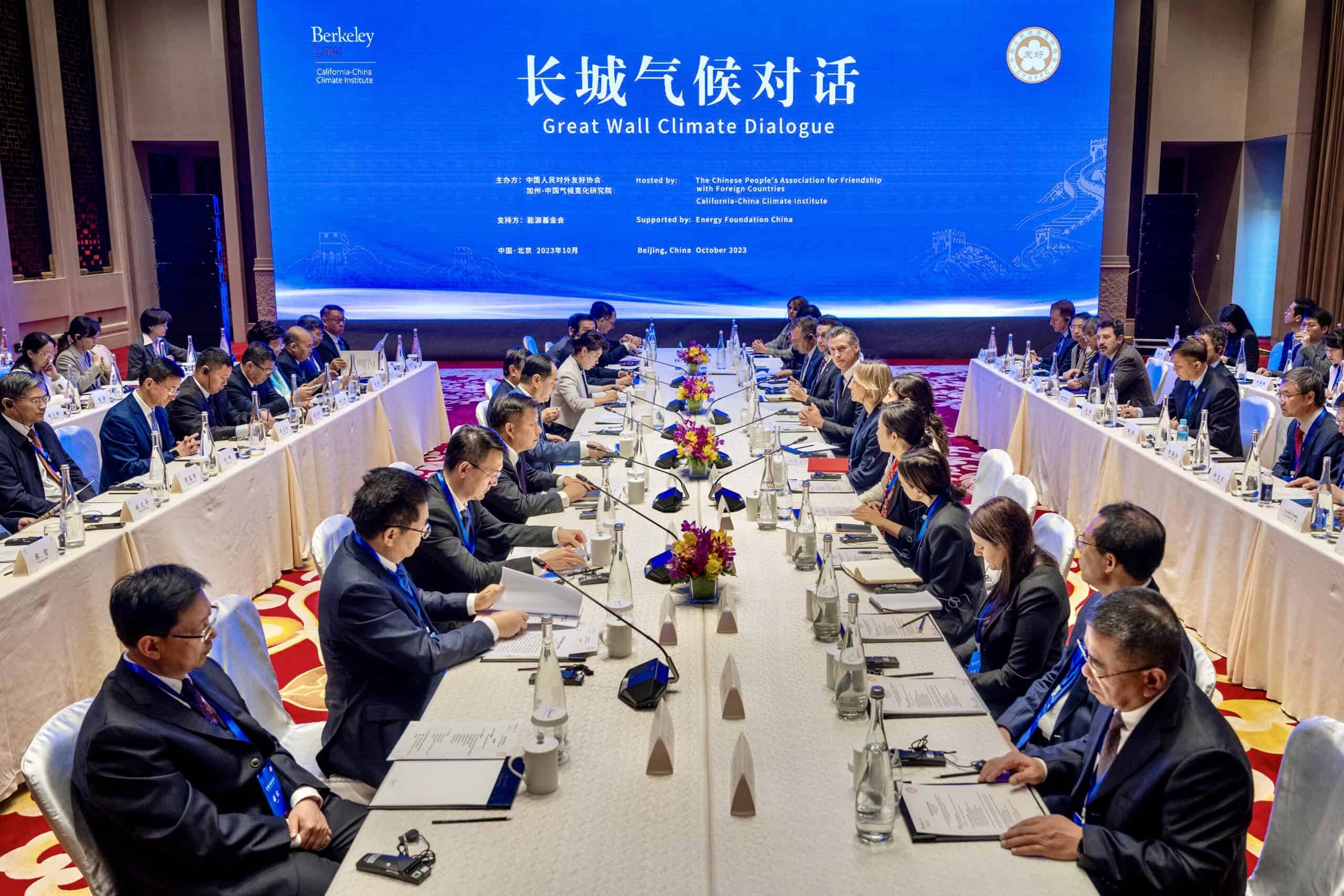

You have co-chaired the China-U.S. Track II Dialogue on Climate Finance and Trade. Now that Trump has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement, is there still hope for climate cooperation between the U.S. and China?

It is now very difficult for China and the U.S. to cooperate in several major green areas — such as photovoltaics, wind power, electric vehicles, and batteries. For various reasons, the U.S. has imposed higher tariffs on China and has been restricting the entry of these Chinese products, or restricting Chinese investment in these fields.

But apart from these areas, there are many smaller green sectors where we can still find opportunities for cooperation, including for bilateral trade, technological cooperation and investment. These include, for example, areas such as plastic recycling, plastic substitutes, waste recycling, waste tire recycling, building energy efficiency, industrial energy efficiency, water treatment technology, and trading of carbon credits.

Recently, our Chinese experts have identified in the Track II Dialogue that there may be potential for cooperation in these areas. One reason is that the products in most of these fields are for civilian usage, and not related to national defense and military matters. Another reason is that such cooperation can help consumers reduce costs, especially as the U.S. faces inflationary pressure. And some of the cooperation can be achieved entirely by the private sector, without the need for government involvement, while some can be carried out with the support of sub-national governments, without involving the federal or central government.

Overall, how important is green finance to the Chinese economy? And can the green economy solve some of China’s problems in the long term, such as slower productivity growth in traditional industries?

In recent years, the incremental GDP brought about by the green economy has been half of China’s total incremental GDP. The green economy may soon overtake real estate as the driving force of the economy.

On the one hand, this is because of its large contribution to the economy, and on the other hand, it is also a major area of technological innovation. A lot of technological development is taking place in the green industry. For example, batteries, electric vehicles, hydrogen, waste recycling, energy efficiency, etc., are all at the forefront of the global technology landscape. There’s a large intersection between technological development and green development, which is driving productivity gains not just in new sectors but also in traditional industries through green upgrades.

Can China become a leader in the field of climate change-related industries? What can be done in terms of climate cooperation between China and its main ‘competitors’ including the U.S. and Europe?

China is already a global leader in key green industries such as solar, wind, batteries, electric vehicles, waste-to-energy, and high-speed trains, in terms of production capability, market size, R&D investment, technologies and cost competitiveness. The U.S. and Europe are still leading in some green tech sectors, such as sustainable aviation fuel, hydrogen storage, CCUS (carbon capture, utilization, and storage), and bio-based materials.

…China and the U.S. should maintain at least educational and scholarly exchanges on climate-related topics via joint research projects, student exchanges, and academic conferences, to avoid an outright decoupling.

I think there is still room for China to work with the U.S. on climate issues. Between China and the U.S., in the coming few years, private sector institutions including corporates and financial firms and NGOs from both sides can collaborate on trade, investment, and technology cooperation (e.g., in the form of technology licensing) in green sectors that do not trigger national security concerns.

More importantly, China and the U.S. should maintain at least educational and scholarly exchanges on climate-related topics via joint research projects, student exchanges, and academic conferences, to avoid an outright decoupling.

Between China and Europe, the scope for climate collaboration is greater, given that both economies remain strongly committed to carbon neutrality goals and are expected by the international community to play a more important leadership role in shaping the global climate agenda, with the U.S. absent in the coming few years.

China and Europe should first settle their own disputes on tariffs on Chinese EVs (possibly via reaching a deal for the EU to remove tariffs while China sells at higher prices in the European market). Building on that, China and Europe can collaborate on a range of initiatives including promoting an interconnected global sustainable finance market, advancing the implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, and building a platform to promote the transfer of green technologies from China and EU to the global south.

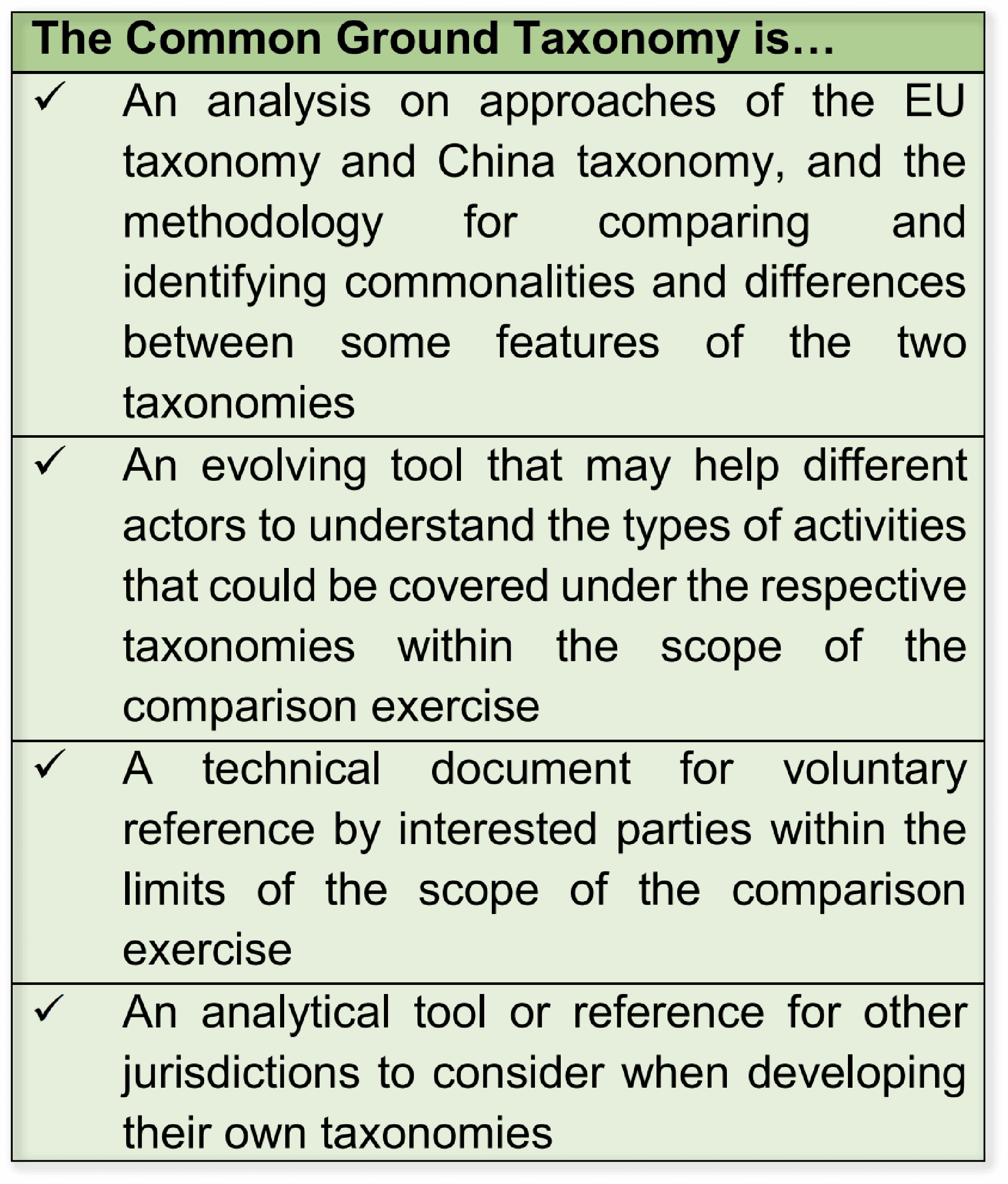

Let me give you a specific example of how China and Europe can work together to provide global public goods. In the field of sustainable finance, China and Europe jointly launched a project called the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT) a few years ago. I was deeply involved in this project as I have been the co-chair of the working group that produced the CGT. The CGT provides the basis for interoperability of the global definitions of green and sustainable activities, thus facilitating green capital flows across jurisdictions. With CGT, a Chinese bank can now issue green bonds using a CGT label and raise funds from many international capital markets without the need to seek verifications against multiple green taxonomies or standards. This CGT project has recently expanded to become a multi-jurisdictional exercise, and has the potential to attract the participation of more countries and jurisdictions.

Capacity building for the Global South is another very important public good that should involve China, Europe, the UK and hopefully the U.S. private sector. At COP28, the Institute of Finance and Sustainability (IFS), which I lead, initiated the Capacity-building Alliance of Sustainable Investment (CASI), with the aim of providing training to 100,000 individuals from emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) by 2030. Last year, CASI delivered training services to 5000 people from about 50 countries. As of now, CASI has developed a membership of 67 global institutions including many from China, the UK, Europe, the U.S. and of course from the global south.

CASI provides a good example of how major ‘green-minded institutions’ from all these jurisdictions can work together despite the complex geopolitical relations that tend to distract our attention from the climate challenge, offering modules on green finance, technology implementation, and policy design.

What about the problem of ‘green laundering’, where Chinese companies may pose as being ‘green’ in order to obtain subsidies?

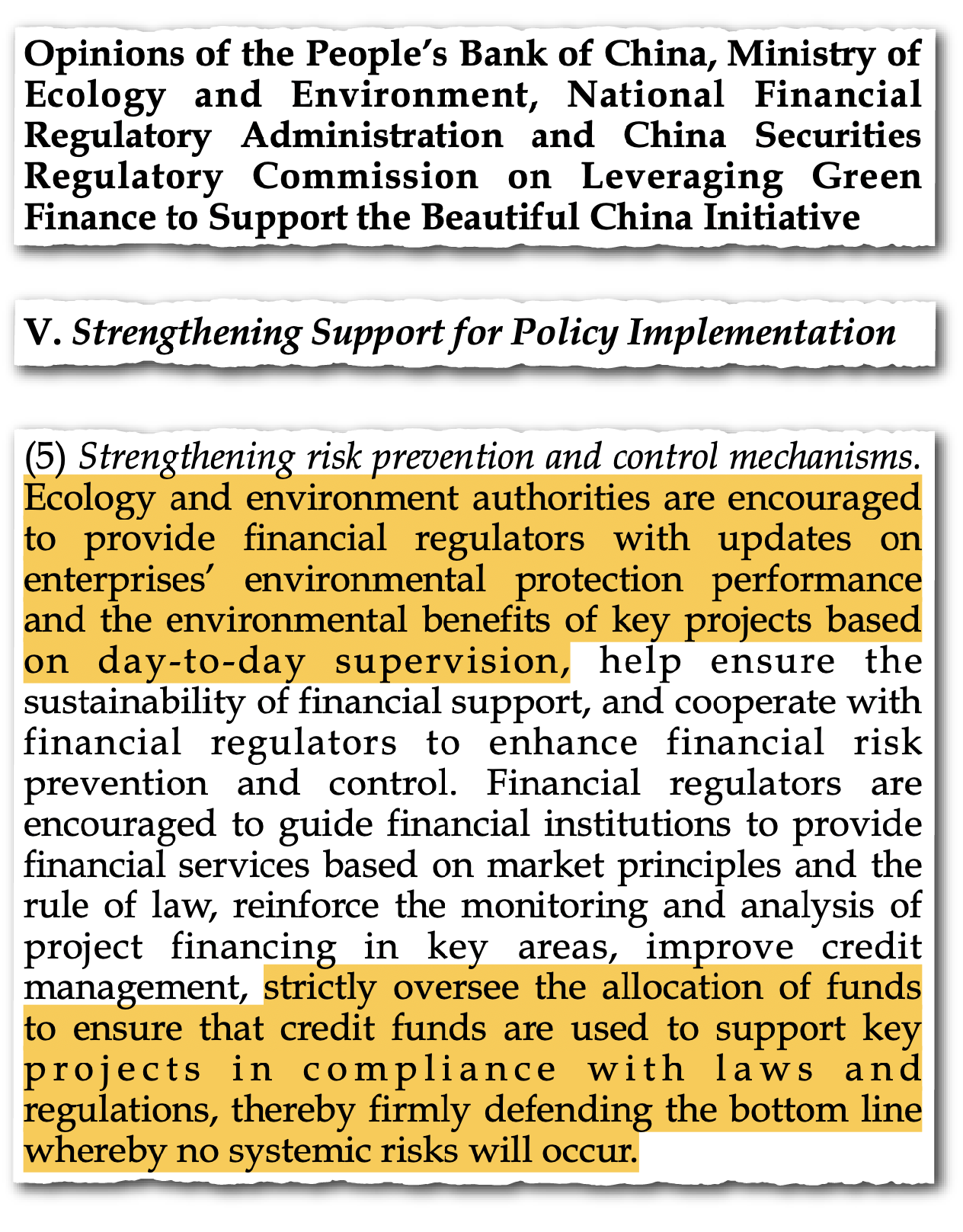

Green laundering, or green washing, can occur in various fields. In countries where regulators do not publish official ‘definitions’ of green activities, do not require mandatory usage of these definitions, and do not require mandatory third-party verifications, green washing tends to be a more serious issue.

…there may be some institutions [in China] that have not fully observed the rules due to incentives to overreport green assets, but thanks to the ‘green’ auditing mechanism… problem institutions that have incorrectly labelled green assets are often identified…

In the past ten years, China has gained some experience in preventing greenwashing in the green lending and green bond market. Essentially, we have set up three lines of defense.

First is the mandatory use of official green taxonomies. These taxonomies are definitions of activities qualified for green finance (mainly green lending and green bonds) published by regulators. These official definitions prevented arbitrary ‘self labelling’ of green projects and green assets, specifying criteria for sectors like renewable energy and energy efficiency. Second is the mandatory requirement for banks to report environmental benefits from projects funded by green loans, and the mandatory requirement for green bond issuers to report environmental benefits to the market — including metrics like carbon emissions reduced or renewable energy capacity added. Third is the auditing mechanism that regulators put in place on checking the green loan credentials provided by banks, and the requirement for second party opinion providers to verify the ‘greenness’ of the green bonds, with penalties for non-compliance.

Is the disclosure policy now complete? Is it working well?

In the Chinese green financial system, the environmental disclosure policy has been in place for nearly 10 years, along with the relevant taxonomies (or catalogues) for green credit and green bonds. Third-party verification policies have also been implemented for many years, especially for green bonds. Overall, these policies have been operating quite well.

Of course, there may be some institutions that have not fully observed the rules due to incentives to overreport green assets, but thanks to the ‘green’ auditing mechanism that was put in place on banks, problem institutions that have incorrectly labelled green assets are often identified and asked to make corrections. For example, banks may be required by regulators to resubmit documentation or adjust their portfolio classifications. Due largely to this auditing requirement, I think financial institutions that deliberately falsify information in their green loan labelling process are rare.

Critics of China often say the country’s government or financial system unfairly subsidizes companies, and so that is one reason why China’s EV and battery makers, or solar companies have been able to achieve so much success. Is that criticism fair or unfair?

In trade disputes, some countries tend to politicize things by attributing trade imbalances to government subsidies of their trading partners to justify their actions, such as imposition of punitive tariffs. More objective studies by serious economists tend to give very different explanations for trade imbalances. For example, an IMF study published in September 2024, based on a quantitative modeling exercise, concluded that ‘the evidence that China’s subsidies have lowered export prices and increased quantities — a combination of effects suggestive of subsidies contributing to excess supply or efficiency gains — is weak.’ The study showed that, except for the chemical industry, it could not find evidence in nine major industries in China that subsidies have helped export competitiveness.

In my view, the key reasons for China’s export competitiveness in many of the green sectors are: 1) massive investment in R&D — e.g., the number of China patents in the renewables, EV, and battery sectors are multiples of those owned by the U.S.; 2) economies of scale that have led to a significant decline in unit costs of production — the scales of Chinese production in these sectors again are multiples of those in any other countries, with supply chains optimized for mass production; 3) a complete domestic supply chain which reduces the costs of sourcing components and raw materials.

Back to the issue of subsidies for green production of consumption, there is a tension between those who argue for ‘fair trade’ and those who argue for accelerating climate actions. The latter camp tends to support green subsidies, as they can induce more consumption and production of green/low-carbon goods and services. That is why many countries have subsidized renewable energy, EVs and other environmentally friendly goods. It is now the job for the trade experts, including the WTO and regional trade blocs, to clearly define what kinds of subsidies are actionable, and should be prohibited in international trade, balancing climate imperatives with trade norms.

Now that the United States has increased tariffs on so many Chinese goods, how much damage do you think it will do to China’s green manufacturing industry?

It has already had some impact, because the U.S. has imposed a 100 percent tariff on Chinese electric vehicles, and imposed various restrictions on imports of Chinese batteries. But the overall impact on the Chinese EV industry is small, as Chinese exports of EVs to the U.S. were a very small fraction of its total production to start with — it accounted for less than one percent of total Chinese production in 2024. The impact on Chinese batteries will be a bit higher, affecting some export-oriented manufacturers.

The good news is that demand from the rest of the world for Chinese green goods is growing rapidly. The first quarter of this year saw nearly 50 percent year-on-year growth of Chinese EV exports to the global south, with markets in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America expanding significantly.

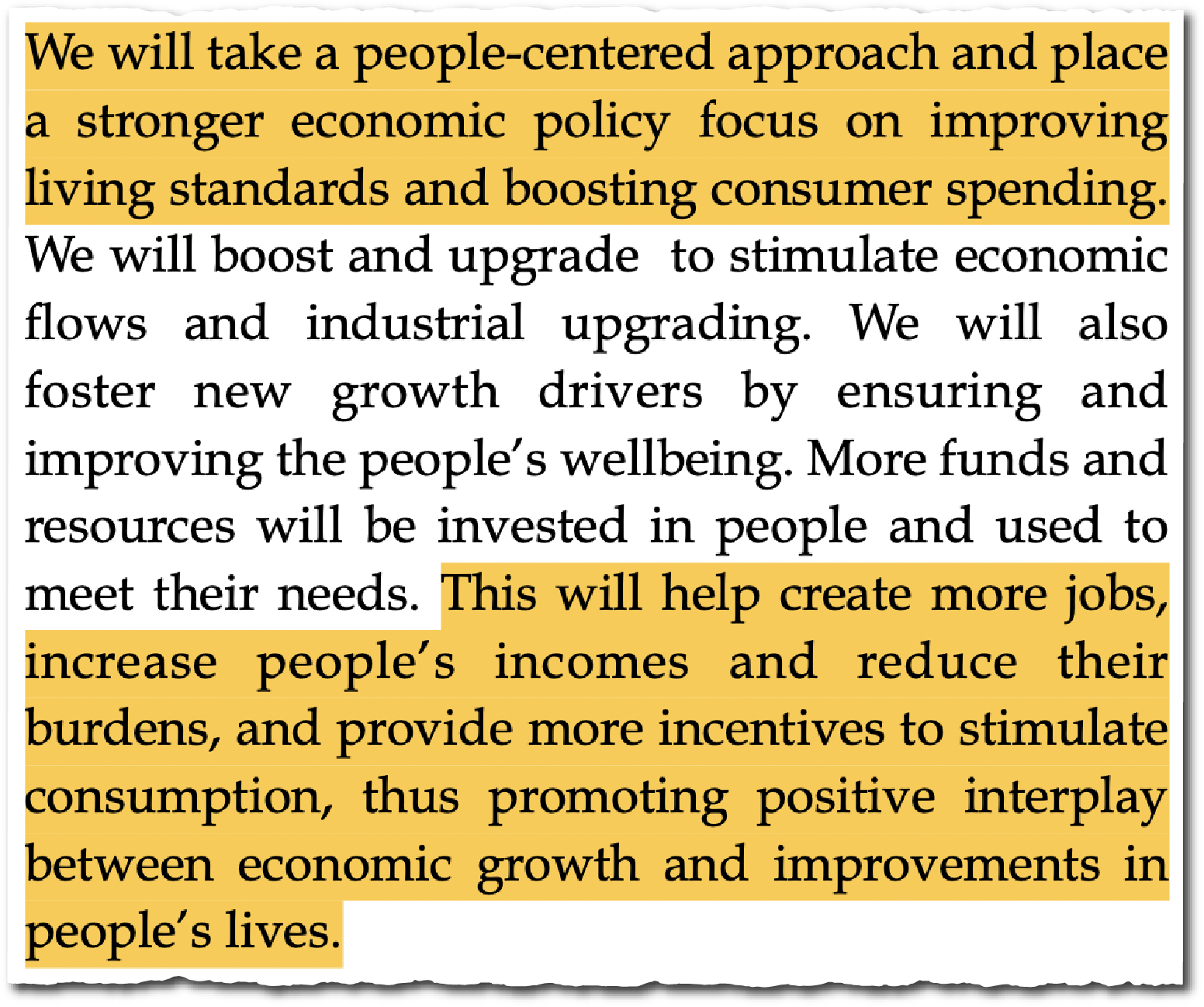

During the pandemic, you said that Beijing should make stabilizing employment the most important economic policy goals. Now what do you think the main goals should be?

In the past, there was an overemphasis on GDP growth as a performance target for local governments. In some cases, GDP and employment goals were not entirely consistent. If there is a clear conflict, my view is that employment should be given priority over GDP.

Historically, boosting short-term GDP growth tends to incentivize a lot of investment especially by local governments, via large-scale infrastructure and housing sector construction, but it does not necessarily create a lot of jobs. Now that physical infrastructure is no longer a key bottleneck, many local governments are facing the problem of excessive debt, and housing demand is weak, I think there is a stronger argument for focusing on the employment objective in macro policy making.

Instead, the policy focus should be on how to boost consumption, including via reforming the social security system to improve people’s willingness to spend money. A lot of people are worried about not having enough money for retirement, healthcare and kids’ education in the future, and therefore refrain from spending on today’s consumption. If the social security system can be established more comprehensively especially for the rural population, so that people believe they will live a decent life after retirement and have the ability to pay for healthcare, they will then be more willing to consume today.

China is now vigorously developing AI and many other technologies, which has the potential to reduce overall employment levels. Do you think the Chinese economy can provide enough jobs for the Chinese people in future? If not, what should be done?

The impact of AI and technologies on jobs is complex. On the one hand, AI does replace jobs, but on the other hand, many other technologies may create new demand and therefore new jobs. For example: if you want to convert a lot of buildings into green and energy-efficient buildings, it’s not just a matter of buying some devices and incentivizing the production of the devices. A lot of manual labor is required to install these devices including replacing its energy systems, windows, air conditioners, elevators, lamps, etc. with more energy efficient or low carbon ones. All of this requires labor during the installation process. Therefore, in some scenarios, technologies and job creation can go hand in hand. Of course, the net impact of technologies on employment is hard to assess, and should be analyzed within the specific country/sector contexts.

Yi Liu is a New York-based former staff writer for The Wire. She previously worked at The New York Times and Beijing News. Her work has also appeared in China Project, ChinaFile and Initium Media.