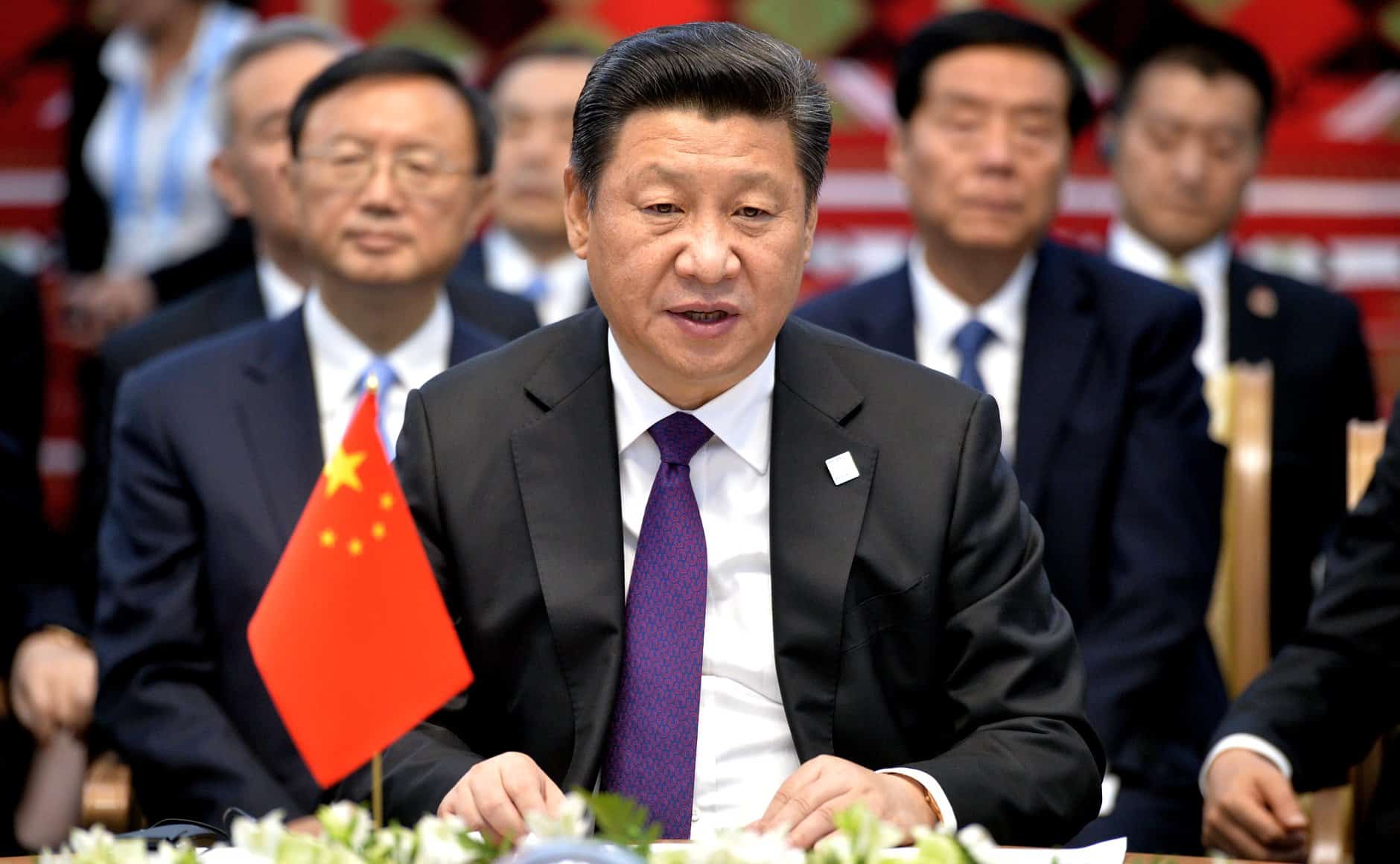

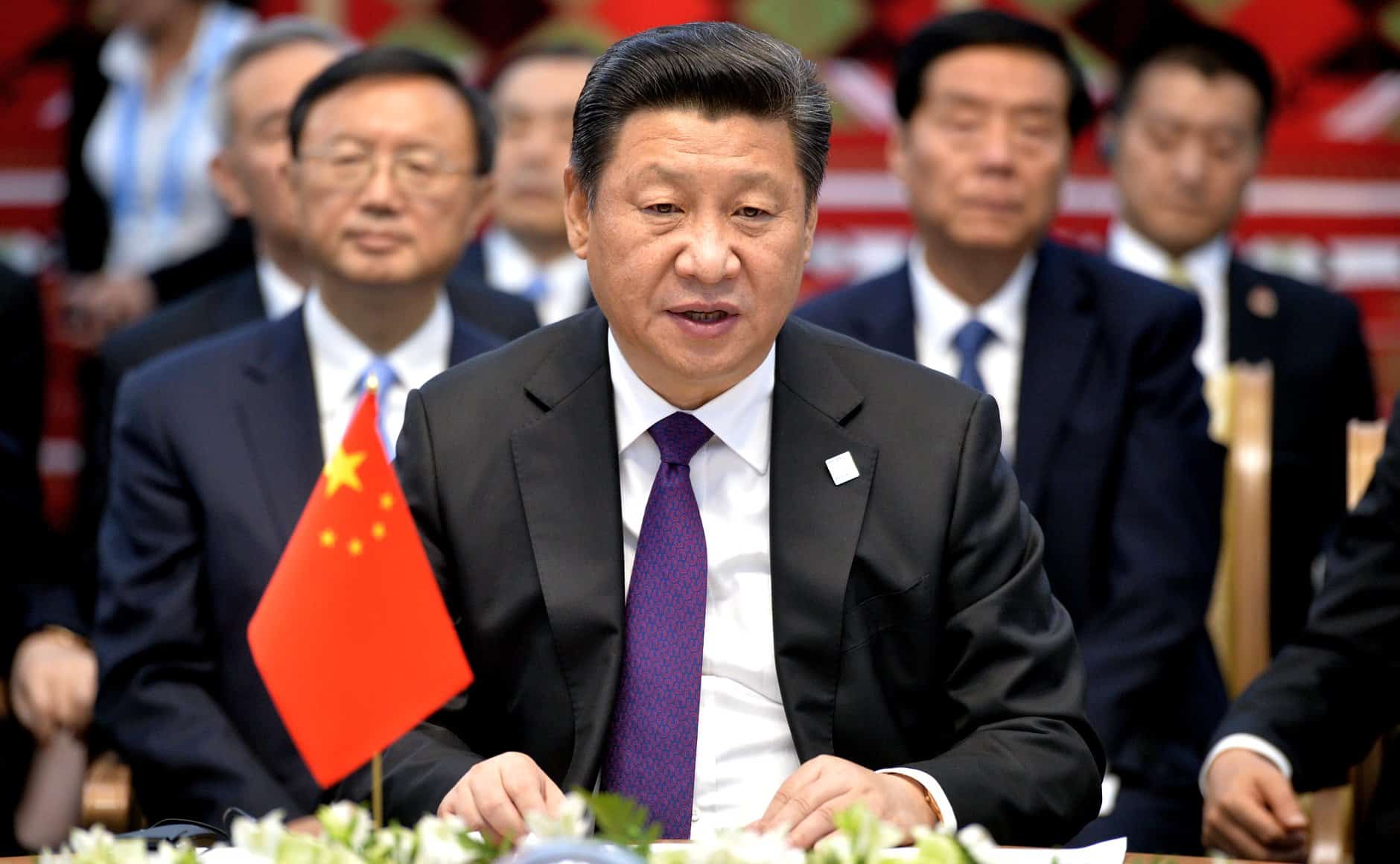

Xi Jinping’s mission to be China’s indispensable leader has been set in stone for some time, at least in his own head. And indeed, it is hard to see anyone in the immediate top circles around him who might emerge as even a remote threat to his position before the Communist Party is due, sometime towards the end of 2022, to hold its five-yearly Congress — a big moment when its elite will either be changed, or reconfirmed in their roles.

Despite a rocky start to this year, the

Subscribe or login to read the rest.

Subscribers get full access to:

- Exclusive longform investigative journalism, Q&As, news and analysis, and data on Chinese business elites and corporations. We publish China scoops you won't find anywhere else.

- A weekly curated reading list on China from Andrew Peaple.

- A daily roundup of China finance, business and economics headlines.

We offer discounts for groups, institutions and students. Go to our

Subscriptions page for details.

Includes images from Depositphotos.com