China may be set to take a major step towards catching up with Western nations in the global vaccine race. Whether that will lead Beijing to change its stringent approach to the pandemic is still open to doubt.

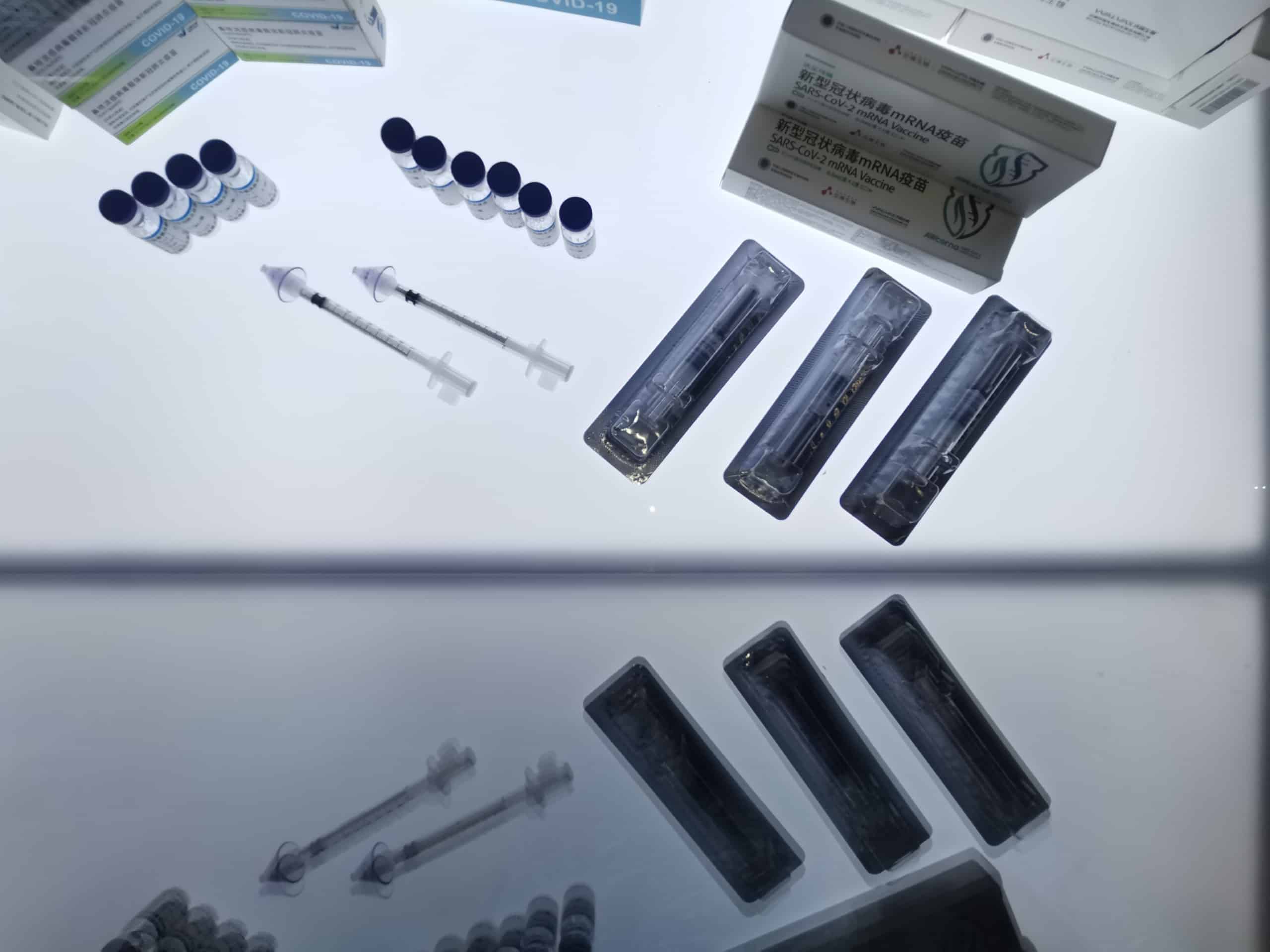

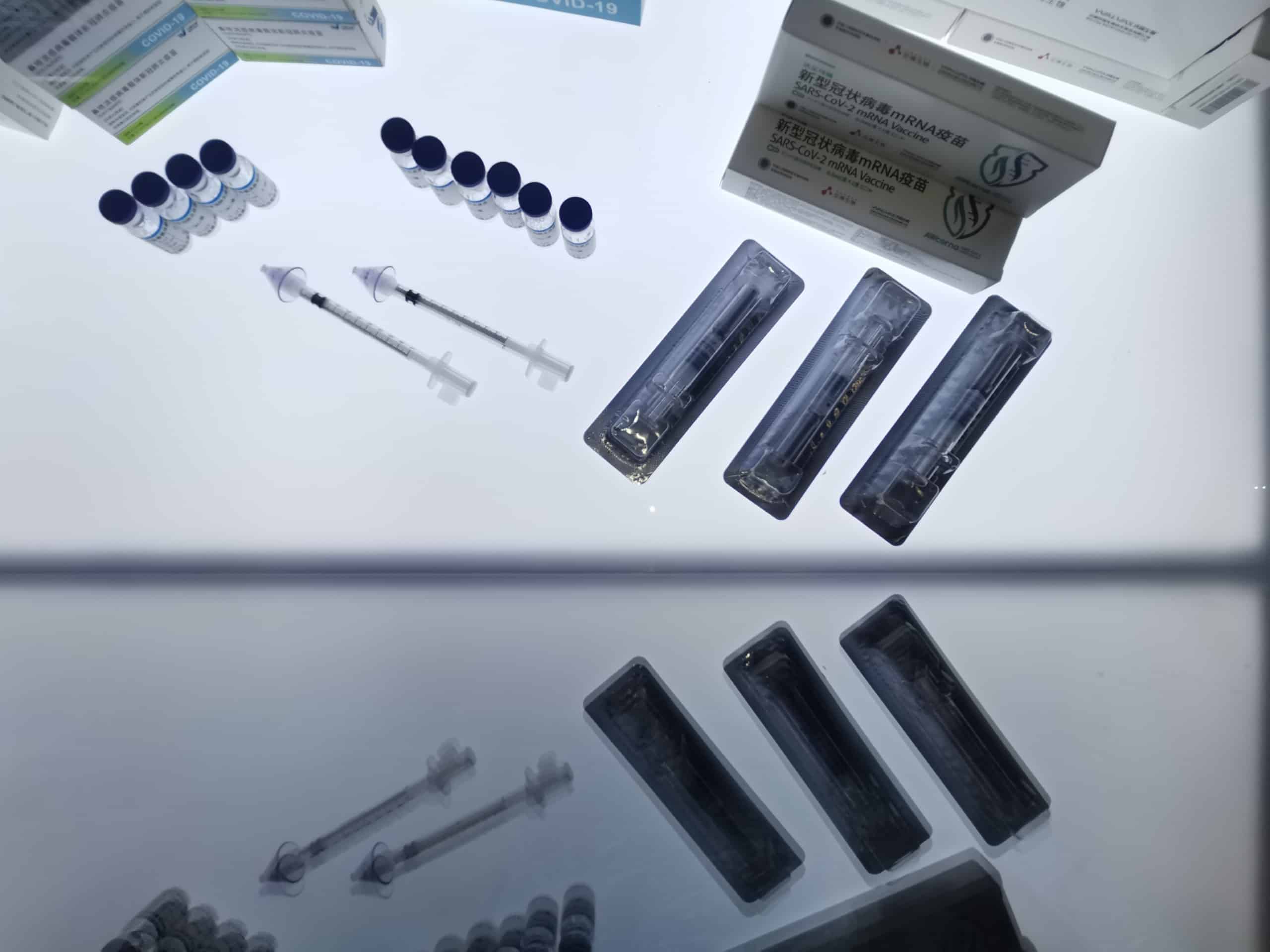

In November, Suzhou Abogen Biosciences and two partners — Yunnan-based Walvax Biotechnology and the Chinese Academy of Military Medical Sciences — received approval from the Chinese authorities to test its new ARCoVax vaccine in a booster trial. If it proves effective, ARCoVax woul

Subscribe or login to read the rest.

Subscribers get full access to:

- Exclusive longform investigative journalism, Q&As, news and analysis, and data on Chinese business elites and corporations. We publish China scoops you won't find anywhere else.

- A weekly curated reading list on China from Andrew Peaple.

- A daily roundup of China finance, business and economics headlines.

We offer discounts for groups, institutions and students. Go to our

Subscriptions page for details.

Includes images from Depositphotos.com