Nathan Law is a pro-democracy activist from Hong Kong. He was one of the student leaders of the 2014 Umbrella Movement and co-founder of Demosisto, a now-disbanded political party. In 2016, at the age of 23, he became the youngest ever person to be elected to Hong Kong's legislature, but was disqualified nine months later after a court invalidated his oath following an intervention from the National People’s Congress Standing Committee. In June 2020, he fled Hong Kong on the eve of the enactme

LISTEN NOW

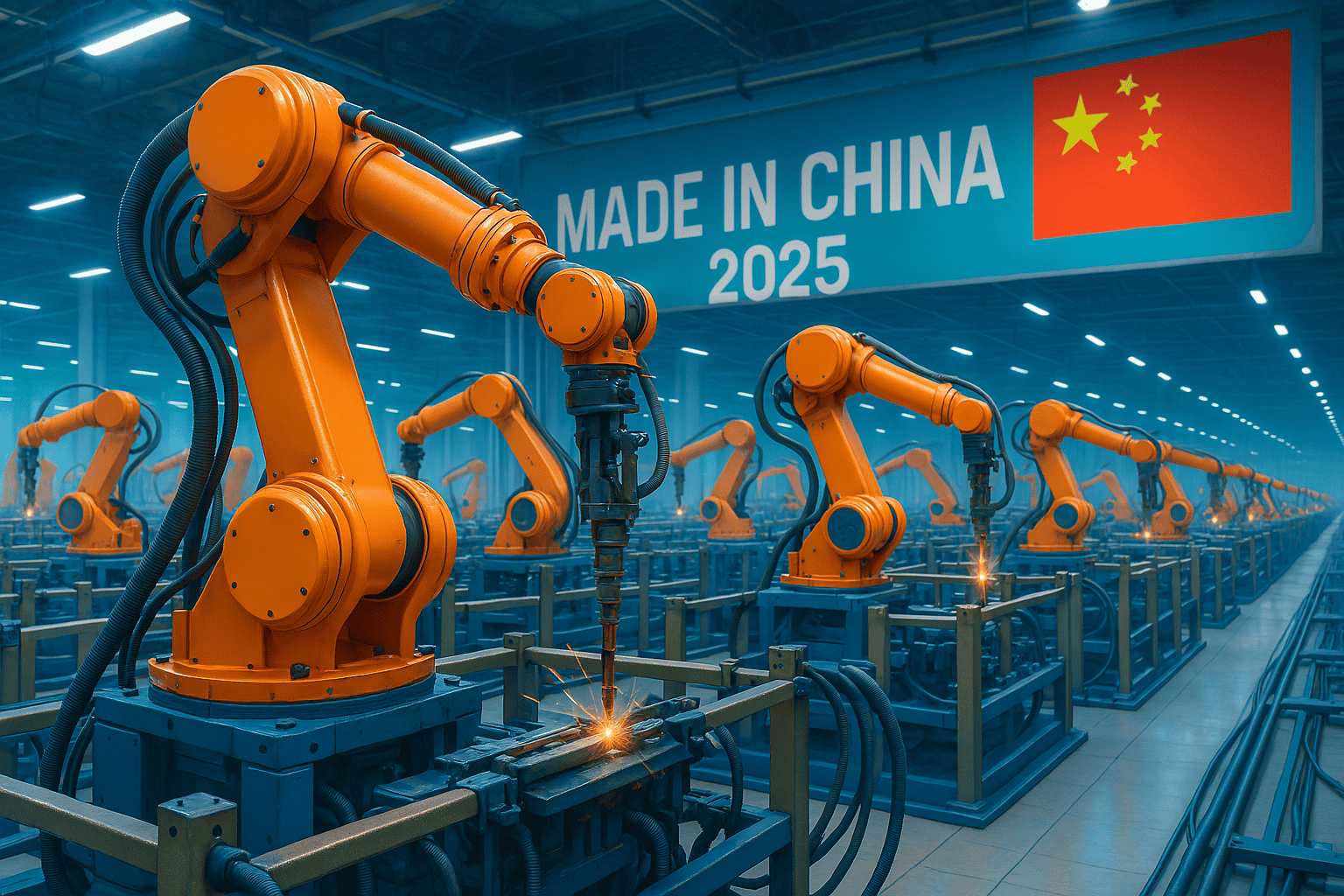

Face-Off: U.S. vs. China

A podcast about the turbulent relationship between the world's two superpowers, the two men who run them, and the vital issues that affect us all.