James Griffiths is a producer for CNN International in Hong Kong and author of The Great Firewall of China: How to Build and Control an Alternative Version of the Internet (2019), which explores how China developed the world’s most sophisticated online censorship system and was released in Chinese on June 4 (游擊文化). He was previously an editor at the South China Morning Post, and his work has been featured in The Atlantic and the Daily Beast. What follows is a lightly edited Q&A.

LISTEN NOW

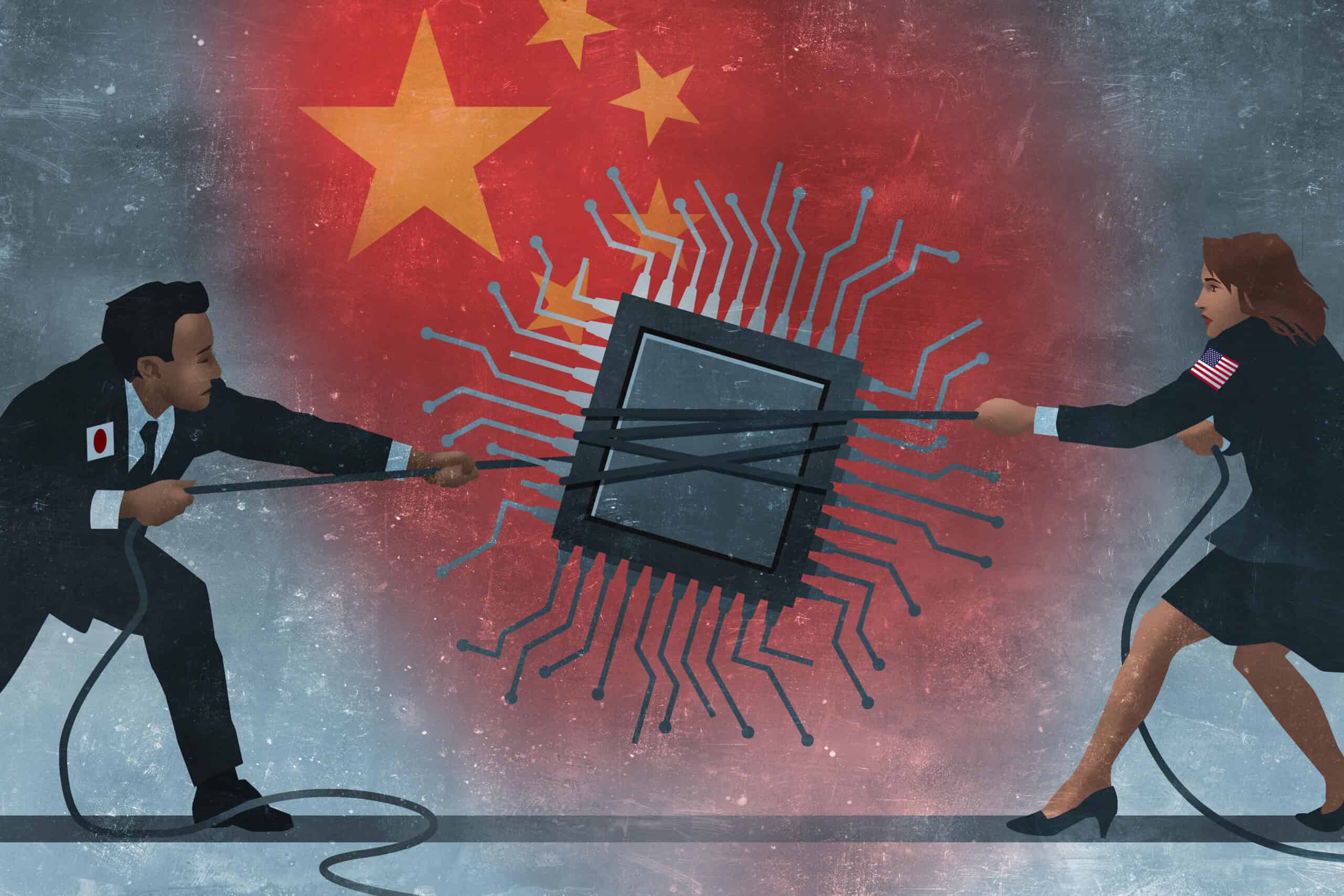

Face-Off: U.S. vs. China

A podcast about how the two nations,

once friends, are now foes.