Frank Dikötter is one of the best-selling historians of modern China, and holds the posts of Milias Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, and Chair Professor of Humanities at the University of Hong Kong. He is best known for his People’s Trilogy which deals with Chinese history from 1949-1976: The Tragedy of Liberation, Mao’s Great Famine and The Cultural Revolution. His new book, Red Dawn Over China, turns to the CCP’s earlier history, tracing its story from the end of imperial rule to victory in the civil war in 1949. Drawing on a wide range of primary sources — including internally published archival volumes from Beijing, Comintern correspondence, as well as diplomatic and missionary accounts — he re-examines key episodes often influenced by the Party’s retrospective myth-making.

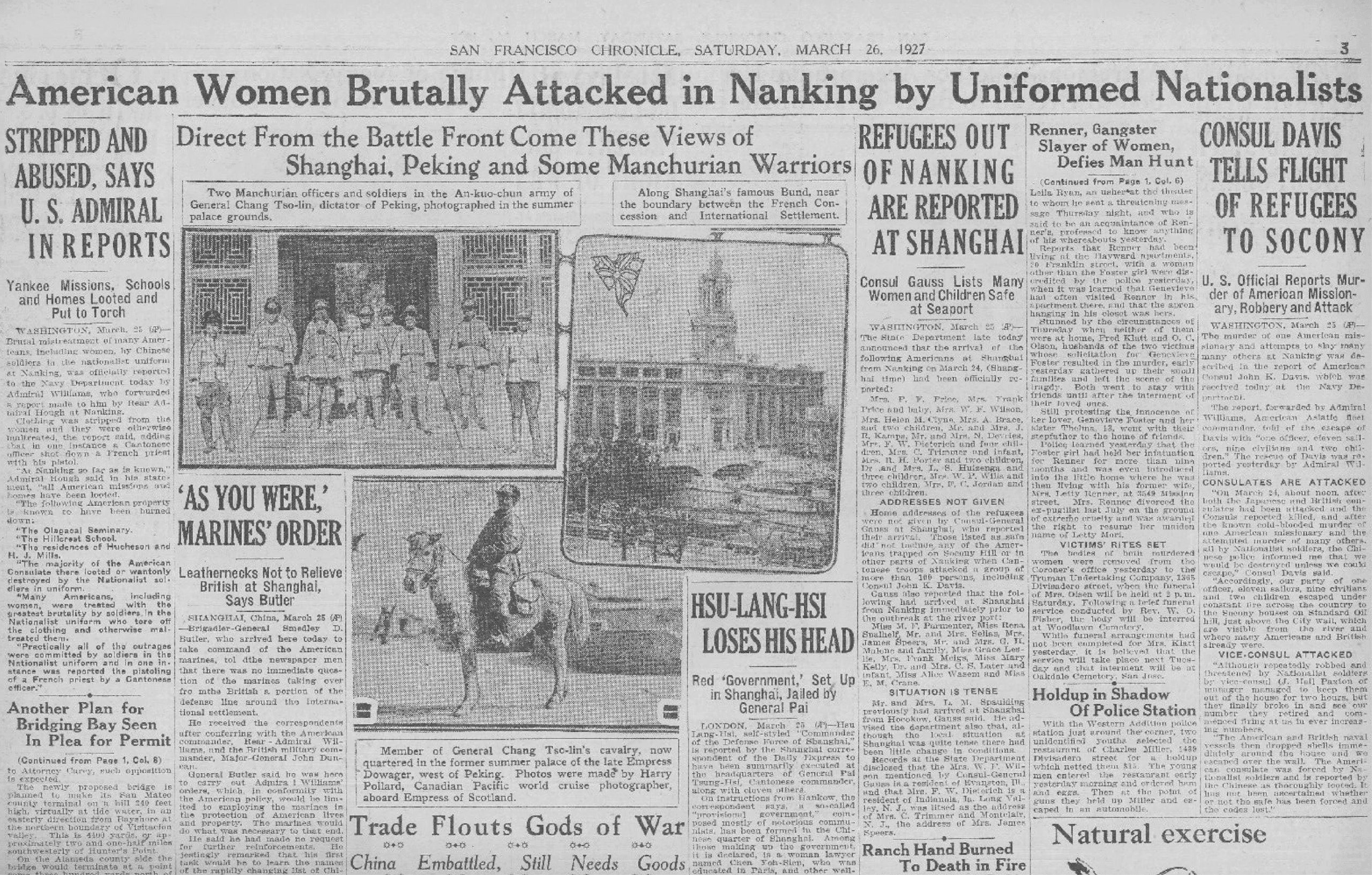

Illustration by Kate Copeland

Q: With this book, you’ve now covered the full arc of Chinese Communist Party history. What prompted you to write this book? Was it a desire for completion, or did you feel there were areas still underexplored in the existing literature?

A: This may seem difficult to believe, but I don’t actually plan things all that far ahead. With hindsight it looks like I did a trilogy, then a sequel, and now logically this is the prequel. But that’s not exactly how it unfolded.

At heart, I’m an opportunist, and an opportunist seizes opportunities. What matters most, from my point of view, is quality primary sources on the one hand, and passion for a particular topic on the other. There has to be a foundation of facts, and there has to be a personal drive.

After I finished China After Mao, COVID hit. It became very clear that I would not be able to travel back into the mainland from Hong Kong. Everything was closed down. So I thought: what can I do? Should I look at the Communist Party from 1921 to 1949? It was something I’d neglected, because I always thought one could get back to that era later on.

But could the era still hold my interest? I tested the waters by picking up a book written by a journalist called John Powell, My 25 Years in China. I thought, let’s see if this can grab me, let’s see if I can develop a passion for this period on which I had already spent 15 years earlier in my career.

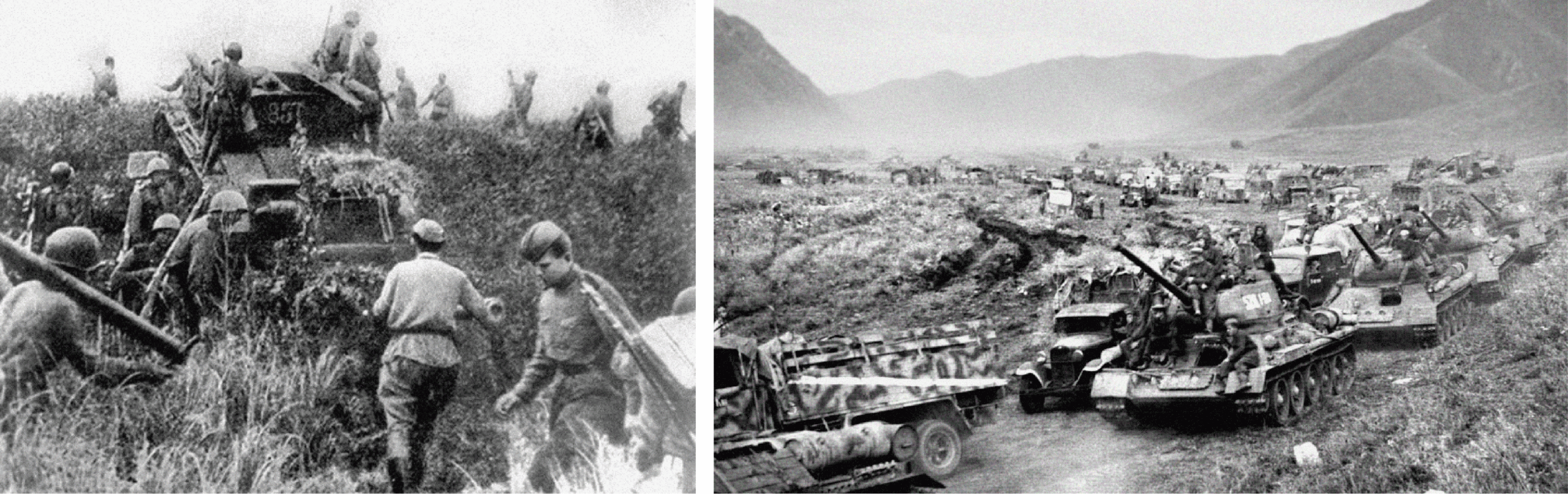

In his memoir there’s a chapter in which Powell, with other journalists, stands on the deck of a boat in Manchuria and watches a Sino-Soviet war unfold in the summer of 1929, with hundreds of thousands of soldiers fighting each other — aircraft, gunboats, entire towns erased, massacres of civilians, a full-fledged war. It struck me that I hadn’t really heard much about the Sino-Soviet war. So I Googled it — this is 2021.

In 2017, a historian called Michael Walker had published a book entitled The 1929 Sino-Soviet War. The subtitle is very interesting: The War Nobody Knew. He explains in the introduction that very few China historians have mentioned this war at all. That triggered my interest.

Something else happened in terms of sources. I found, in the Library of Hong Kong, a number of volumes compiled between 1981 and 1989 by the Central Archives in Beijing. They went around the country collecting every scrap of paper from the Communist Party written between roughly 1923 and 1949. They compiled these sources in a series amounting to some 300 volumes, but all published internally, or neibu. In other words, you could not buy these at the time or find them in a library. They were restricted for the eyes of the leadership only.

| BIO AT A GLANCE | |

|---|---|

| AGE | 64 |

| BIRTHPLACE | The Netherlands |

| CURRENT POSITIONS | Milias Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University Chair Professor of Humanities, University of Hong Kong |

So I thought: wow, that’s very interesting. I started going through them, and thought that they made a very good basis for this project. That’s how I got into it.

When you moved into the pre-1949 period, did the research process feel different? Compared with your post-1949 work, did you find the trove of primary sources richer because of treaty-port observers, journalists, and other foreigners on the ground?

Yes. I was literally crossing the border back into pre-1949. My first five or six books were on the republican era, and I always thought there was a bit of sinological fetishism about that period: sinologists insist on Chinese sources, but there were foreigners who — like John Powell — spent decades in that country and knew it very well.

On the one hand, I had these 300 volumes published internally by the Central Archives in Beijing. On the other hand, there’s so much material from other parts of the world.

| MISCELLANEA | |

|---|---|

| FAVORITE BOOK | Anything by George Orwell |

| FAVORITE FILMS | Fargo, The Big Lebowski, Mulholland Drive |

| FAVORITE MUSICIANS | Bach and Hendrix |

| MOST ADMIRED | My wife |

The Russian material is absolutely fundamental. I would go so far as to say that if you cannot read Russian, then working on the Communist Party before 1949 is not going to be very successful. All the correspondence of the Comintern — the Communist International established in 1919 with the express purpose of overthrowing the “international capitalist class” — can be found in something like five fat volumes, and they are fundamental.

But also, interestingly enough, the French and the Brits. The British archives are very easy: you can go to the Public Record Office in Kew, or you can just download a great many of them. A huge amount is online.

Who writes in great detail about the very early days of communism — 1919 onwards — when the first Comintern agents are sent to China? It’s obviously the Brits. They’re in all the concessions, and they’re worried not just about communism in China, they’re worried about communism in all of Asia. Their sources are much more detailed than many others one might normally turn to.

And then there are the French. They’re Catholics, which means there is probably a missionary in every county, including the poorest parts of Yunnan or Sichuan. Thanks to some of their reports, one can actually get a much better idea of what the communists were doing on the ground — in particular for the Long March. They can be found, of course, in France, and I used a great many of them.

So yes, post-1949, the bamboo curtain comes down. You must rely on whatever you can find in local archives. But when it comes to pre-1949, China is very much part of a global world, with much greater diversity of source material.

That early Republican period is notoriously complex — especially the First United Front (1923-27) between the nationalists and communists. How did you structure the book to make that phase legible, and did you find it confusing as you worked through the material?

Yes, it’s a bit like the Cultural Revolution, but worse.

…a United Front — whether formal or indirect — from a communist perspective can always be an alliance with your worst enemy, whom you can then defeat later on.

For starters, we sometimes forget that we’re talking about a country the size of Europe. We think the European Union is a great achievement, but to unify — to impose some measure of administrative and political unity — on a country the size of all of Europe is not easy (whether it is desirable is a different question).

There were a lot of provincial governors (called “warlords”), ever-shifting alliances, pacts, two united fronts, provinces, capitals, battles, and what appear like endless names of politicians and generals. That’s incredibly difficult, not least for readers who may not be specialists.

But the key point is that when you read through the volumes published by the Central Archives, you realise that the Communists were actually a very minor political force. The extent to which the Communists, all the way from 1921 to 1940, constituted a tiny fraction of the overall population and attracted very little popular support was not entirely clear to me. The history of those two decades is often presented as a contest between the Nationalists and the Communists, as if they were on a par.

Just to give your readers a sense of proportion: there were vastly more Communists, as a proportion of the overall population, in almost any country in Europe — with the exception of Nazi Germany — than there were in China throughout the 1930s.

In 1934, under Antonio Salazar in Portugal, one in 280 people is a Communist Party member, despite repression. In Finland in 1935, where the Communist Party is outlawed, one in 700 people is a party member. In China, it’s not till 1940 that there was even one Communist party member for every 1,700 people, if you believe the inflated figures produced by the Comintern, which is roughly the same as in the United States at the time.

So I realised you don’t have to tell the story of this entire country. If you focus on what they do and how they move forward, while maintaining that sense of proportion, then it becomes a bit easier.

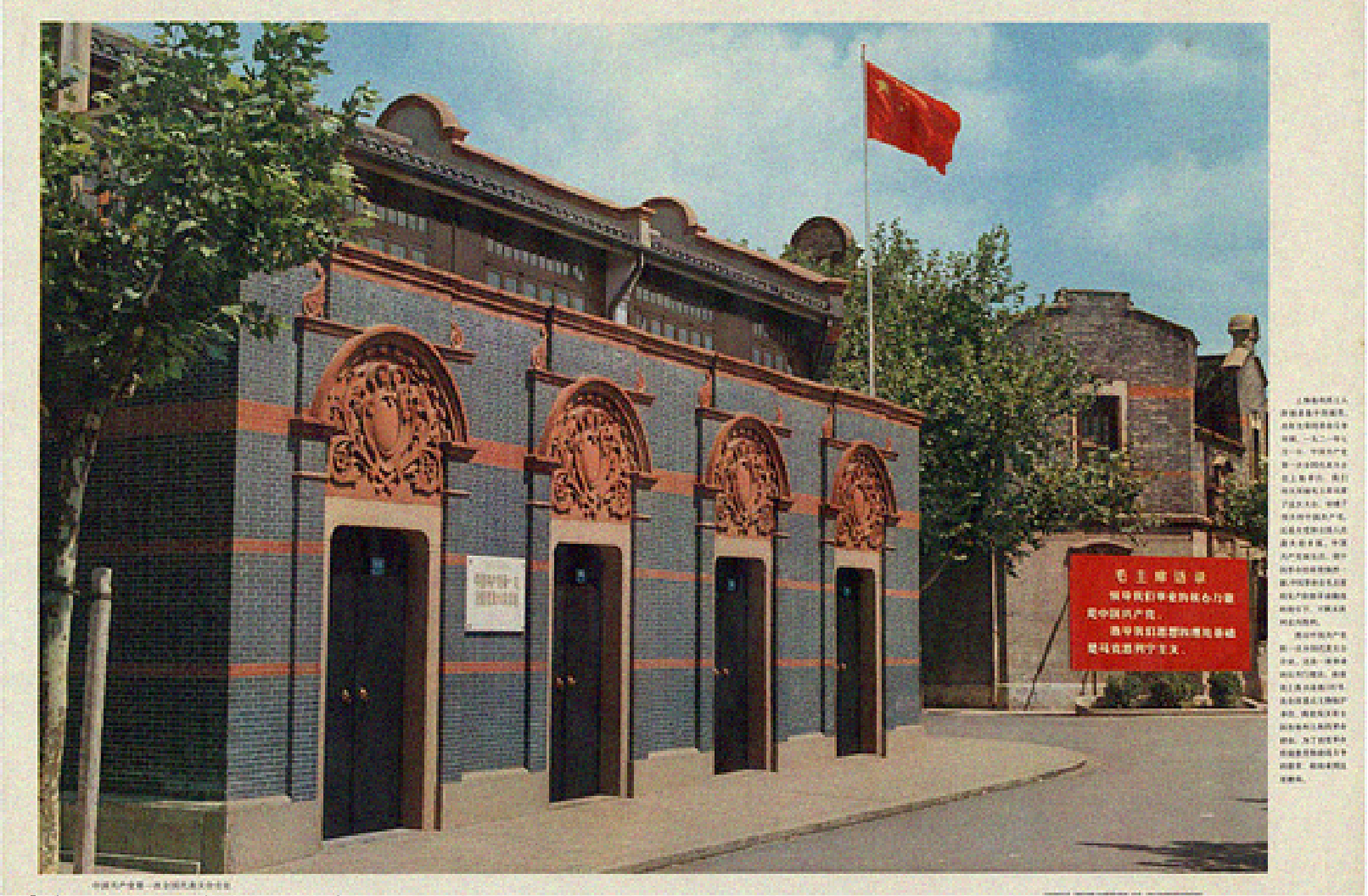

CCP historiography and propaganda presents the First Party Congress at Bowen Girls School in Shanghai (1921) as a decisive founding moment for the Chinese Communist Party — some of our readers might have visited the museum that today stands on that site. In your account it feels far less significant. How should we understand what actually happened in 1921, and why it mattered — or didn’t — at the time?

At that meeting there were only a dozen people. The most interesting thing is that the two founding fathers — Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao — weren’t there at all.

The usual account is: 1917, Bolshevik Revolution, Lenin. This inspires people in China, and the Communist Party is established in 1921. That’s not really the case. Very few people are interested in communism at all at this point.

And then there’s another point. I’m Dutch; I don’t want to say I’m proud of what Henk Sneevliet did, but he was the Dutch Comintern agent who actually got those twelve people into that room. He’s also the one who realised — along with Lenin, by the way — that there were so few people in China interested in communism that the only way forward was a United Front with the Nationalists under Sun Yat-sen in Canton (Guangzhou), which happens in 1923.

So it was Comintern agents who are actually the architects not only of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921, but also of the United Front in 1923.

We’re talking about what would be considered antiquarian history: in a country of about 400 million people, you focus on a dozen.

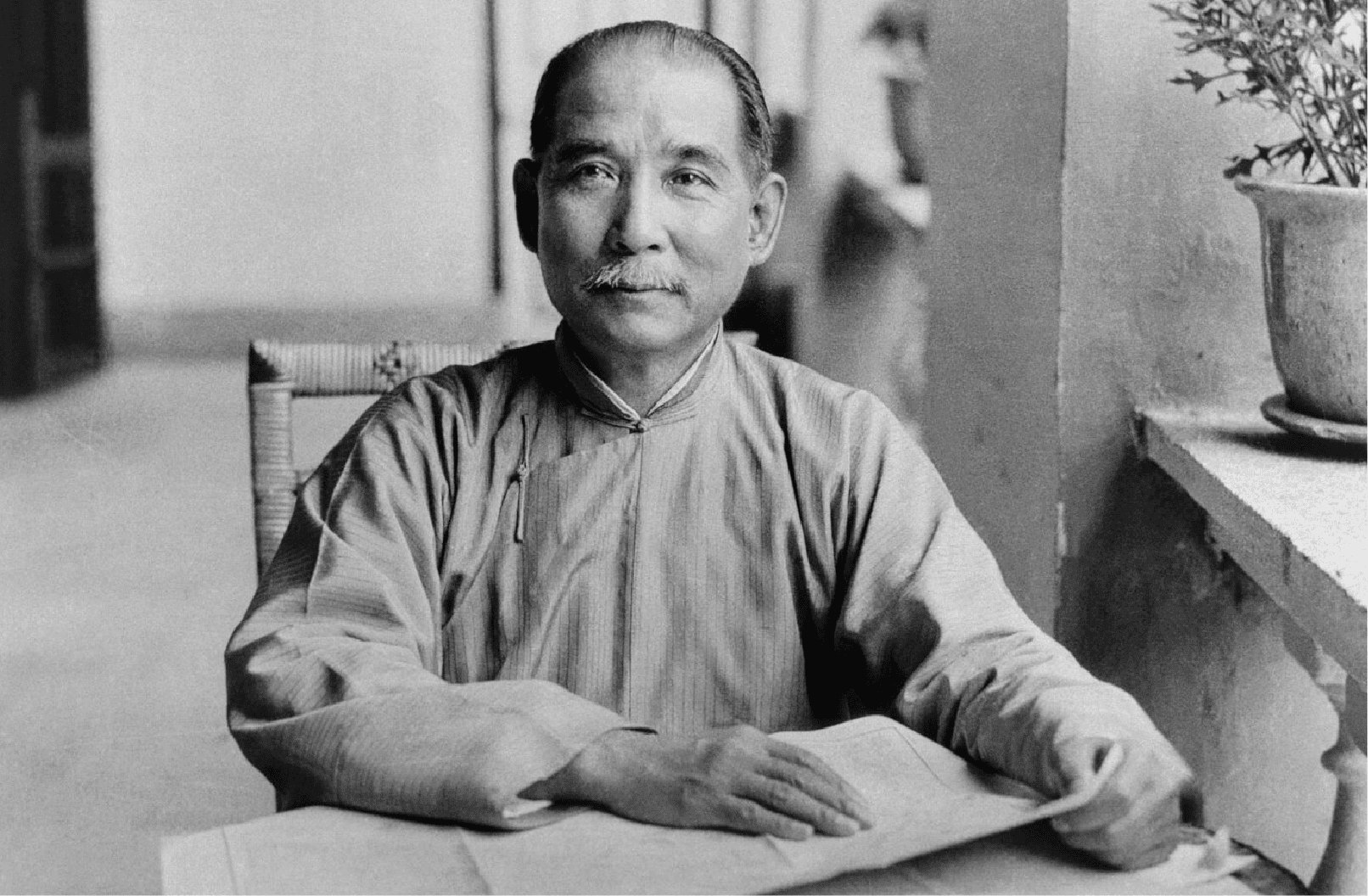

In the first United Front (1923-27), it’s clear what the Communists gain: entry into a far larger political movement, military training, and a measure of cover within the Nationalist alliance. What did the Nationalists think they were getting, and why did they accept Communist Party members into their ranks?

Why do they accept a Trojan horse?

The Nationalists under Sun Yat-sen need help. They need weapons. They need money. And Moscow says: we can provide all of it, but you must accept Chinese Communist Party members inside the ranks of your own party.

They think they will be able to control them, but they won’t.

You’ve got to remember: the Soviet Union sends not just weapons by the boatload, but also hundreds of advisers, including a man called Mikhail Borodin.

And he’s pretty much in charge of the army built up by the Nationalists in Canton. Imagine your country being diplomatically recognised by another country which actually funds, trains and directs a huge army intent on overthrowing your government on your territory.

A theme running through your work is the Communist Party’s amoral pragmatism — the idea that ends justify means, and alliances are purely instrumental. How do you see that operating in this period, especially through Soviet strategy and United Front politics?

Yes. I think there’s a fundamental point there.

First of all, Stalin is extremely pragmatic, and he hedges his bets all the way through, including right up until 1949. He’s always trying to see if there’s someone else he can bet on.

He does so with Feng Yuxiang, the so-called “Christian General”, or “warlord” in the north. He does it with the Nationalists.

I’m always interested in evidence, whichever way it goes. I’m not out to find the most horrendous incidents or to give the worst impression of the CCP.

He’s no fool. He realises, particularly in 1936, that the Nationalists — now the central government with something like two million troops — are a much more reliable partner to fight Japan, the fascist enemy of the Soviet Union, than the 40,000 soldiers of the Communist Party hiding somewhere in the hinterland.

But the key point is that a United Front — whether formal or indirect — from a communist perspective can always be an alliance with your worst enemy, whom you can then defeat later on.

CCP historiography frames April 1927, which effectively marked the violent collapse of the First United Front between the Nationalists and Communists, as a major betrayal and “massacre” in Shanghai. In Party narratives, Chiang Kai-shek’s suppression of Communist-led unions and militias is often presented as a decisive moment of martyrdom and rupture. What do the sources suggest actually happened on 12–13 April 1927, and how should we understand that turning point?

I was always bemused and puzzled by the account of what happened on the 12th and 13th of April 1927.

As the Northern Expedition moves forward in 1926, the entire South of China is seized by the Nationalists. The Communists inside their ranks create havoc. Boatloads of foreigners, merchants, landowners and their families come down the Yangtze to find refuge in Shanghai.

When the Nationalists enter Nanjing in March 1927, the Communists in their midst instigate an attack on foreigners, including the Japanese consul, shot twice, and the vice-president of Nanking University, shot dead. The Nanking Incident makes headlines throughout the world, as a dozen foreigners are killed, their residences ransacked and burnt.

Will Shanghai be next, is the big question.

Chiang Kai-shek writes in his diary that the strategy of the Communists is to provoke a foreign intervention. He is right, as we can tell from the Soviet documents. He wants to get rid of the political commissars, all of them Communists, who are responsible for the ideological control of the troops.

Then something else happens. Even before the Nationalist Army takes Shanghai, local militias take control of the city outside the foreign concessions. They are heavily armed and directed by the Communists.

Chiang Kai-shek gives them several days to surrender their weapons. They don’t. So on 12 April, he sends in the army to disarm them. The pickets barricade themselves into several buildings. Dozens of people die as both sides fight each other.

The following day, despite martial law, there is a large demonstration organised by the Communists, who demand that their weapons be returned. The parade rapidly turns into chaos. Soldiers first shoot in the air, then into the crowd, with absolutely horrific consequences.

But the number of dead on those two days is counted in the low hundreds. Some names are published in newspapers. No one at the time claims that 4,000 Communists were massacred in the streets of Shanghai. That claim is made much later, even by historians I otherwise respect.

From late 1927 into the Jiangxi Soviet — a major Communist-controlled base area in rural southeast China — and then the Long March of 1934–5, CCP historiography portrays an era of heroic consolidation. What do the archives suggest the reality was?

We’ll skip 1927 to 1931, when they are roving around in the countryside, unable to seize or keep territory. Then Stalin insists that they establish a Soviet.

There are several by 1932, but the point is that the CCP is unable to run an economy of any size. Their inability to run an economy remains a handicap all the way until 1949.

The Communists seize bits of territory along the border of several provinces that are frequently inhospitable — mountainous regions where villagers already struggle just to feed themselves. Now these impoverished people must feed themselves as well as soldiers and party leaders. It’s simply not possible.

The biggest myth is land reform, namely the idea that by confiscating land from wealthy landlords and giving it to the poor the Communists can create a surplus. It doesn’t work like that. These villages are all mired in poverty. There are no landlords.

But the Party must extract grain to feed the troops and recruit men to build up the army. Eventually there is no one left but women cultivating the fields.

Assets are confiscated first from those described as “rich peasants”, then from “middle peasants”, and then pretty much from anyone left standing. At a certain point, villagers begin to slack, knowing full well that what they produce will be confiscated.

There’s a wonderful sentence in the archives: “The farmers became lazy.” The Communists themselves describe how arable land lays fallow, even as the local population goes hungry. One party leader observes: “It was like serfdom in feudal times”. In a nutshell, the Communists squeeze the territory they seize like a lemon and are forced to seek greener pastures elsewhere once they have ruined the local economy.

When seven members of the Central Military Commission are reduced to a mere two, and one of these is Xi Jinping, you learn something about paranoia and lack of trust.

There were also constant purges against presumed “counter-revolutionaries” and other suspects, instilling fear in everyone. In one Soviet straddling Hubei and Hunan, poor villages inside the Soviet are incited to attack other poor villages outside the Soviet. One leader writes that “We sent our peasants to white areas, we stole their resources, we were like colonisers.”

Eventually, after the central government builds blockhouses around the Jiangxi Soviet, more and more villagers are able to flee. What is a trickle becomes a flood. By the time Jiangxi Soviet collapses in October 1934, children aged seven or eight are being encouraged to join the Red Army and “sacrifice their blood”.

They are forced, yet again, to move on with the Long March. 80,000 leave in October 1934 [from their base in Jiangxi]. Perhaps 6,000 or 8,000 arrive a year later at Yan’an [in northern Shaanxi province]. This is seen as a victory.

What struck me on reading various accounts, including reports by French missionaries, is that, not to put too fine a point on it, it was a massive cock-up. More than once they go around in circles, with access to supplies and easy terrain repeatedly blocked by the central government. It is Chiang Kai-shek, not Mao Zedong, who is practising guerrilla warfare. “They run as we rest,” the Generalissimo points out, until “in the end they collapse altogether”.

By the end of 1936 there were roughly 40,000 Party members surviving in a country of half a billion.

Who comes to the rescue? Stalin, once again, who yet again says that they must form a united front with the Nationalists and fight the Japanese. Imperialism, in any event, is no longer the main issue. The unequal treaty system, rightly denounced by the Communists in the early 1920s, is systematically dismantled in the decade after 1926. China has changed, but not the Communists.

To take one specific example of divergence from the official version: the Luding Bridge episode of the Long March is iconic in CCP mythology. Your archival work revealed a rather different reality to the oft-repeated story of Red Army soldiers clambering across the chains of a bridge, above a rushing torrent — all whilst under heavy fire.

I’m always interested in evidence, whichever way it goes. I’m not out to find the most horrendous incidents or to give the worst impression of the CCP.

For instance, as a student I read that the Communists buried people alive in Hunan province in 1941–42 — an allegation made by a French missionary, but also by Jacques Guillermaz, who was the French military envoy during the Second World War to China and later became an eminent historian of the Communist Party of China in Paris.

I didn’t really believe it; I thought it sounded like reactionary propaganda.

But once you see it reported in a number of documents, then it becomes quite convincing. Should you then ignore it? I don’t think so. And it was the same with the Luding Bridge Incident.

On two occasions, witnesses in their 80s were interviewed, and both of them simply denied that any fighting took place at all. The Communists came, unhinged doors from several households, put them on the chains, and walked across the bridge. No shots were fired, no fire was set on the bridge.

So I thought: maybe this is true, maybe it’s not. Memory is a tricky thing.

Here I am in the French archives in the summer of 2022, reading through missionary accounts, and I see a letter by Père Valentin. Père Valentin, like many other missionaries, has spent decades in the region. He lives in Luding, and writes a report on what he saw for the consul in Chengdu. He says clearly that the troops on the ground did not fire even a single shot at the Communists. His account coincides exactly with what the two witnesses remembered decades later.

His account also points out that the Long Marchers looted the local orphanage, burnt the local market and took anything that they could carry with them.

Your title clearly alludes to Edgar Snow, and you treat Red Star Over China — his influential 1937 book based on time spent with Mao’s forces in Yan’an — as pivotal in shaping international perceptions of the CCP. What was life amongst the CCP in northern China after the Long March actually like, and how does it diverge from Snow’s account?

Yes, Red Dawn Over China is a direct echo of Red Star Over China, which I read as an undergraduate student. Fascinating, but I didn’t quite believe it. A bit of a David and Goliath story in which sympathy goes to the boy with the sling.

Edgar Snow arrives in 1936 when the red star is at its lowest. Party membership is in the tens of thousands. He becomes their mouthpiece, producing a riveting bestseller translated into many languages. He puts Mao and the Communists on the map.

That account — Communists fighting imperialism, feudalism and fascism for a better world of freedom, justice and equality for all — is extraordinarily powerful. To some extent, much of the later CCP propaganda comes from that one book.

From 1937 onwards, Mao’s Soviet in Yan’an is recognized by the central government in a United Front engineered by Moscow. The Communist troops are paid for by Nanjing. I didn’t quite realise that 75 to 90 percent of the finances in Yan’an came directly from the coffers of the central government.

Mao advertises Yan’an as a “New Democracy”, promising a multi-party system, democratic freedoms and protection of private property. It was an entirely fictitious programme.

Behind the scenes, from 1942 to 1944, there is an extraordinarily brutal purge. Tens of thousands go through the wringer, suspected of being “enemy agents” or “spies”. Several thousand are shot, including Wang Shiwei, whose crime was questioning systemic inequality, with leaders eating their fill whereas ordinary people were starving.

I no longer feel that I have to quote somebody because that person agrees with me, or not quote a book because its author disagrees with me. My compass, moral and otherwise, comes from the primary sources.

Yet again, the Communists ruin the local economy. In 1941 both central government contributions and Soviet financial support end, and the region rapidly plunges into famine. They manage to survive by cultivating opium.

This is not something I discovered. Earlier historians established much of this, not least Ch’en Yung-fa and Gao Hua, but it has often been sidelined. It doesn’t fit the David and Goliath story.

Given its small numbers, near-collapse, and dependence on external backing — how did the CCP ultimately win the Civil War?

That’s a very good question.

It goes back to the title of a book by Lucien Bianco I mentioned earlier on — The Origins of the Chinese Revolution. There’s a conviction among so many of us that there must have been social, economic, political reasons for a revolution to take place. Revolutions don’t just happen for nothing.

But my answer to that is: no, there wasn’t a social revolution. There was a military conquest.

Would you look for the social origins of communism in East Germany or Poland? No, because you know that the Communist Parties there were imposed by the Soviet Red Army in 1945.

Similarly, a million Soviet soldiers marched into Manchuria in August 1945. They stayed for a long time, and handed over the countryside to the Communists.

The Americans helped too, forcing a coalition onto the central government, which was already struggling to rebuild a country devastated by eight years of warfare, with towns and cities lying in rubble. Then in September 1946 Washington imposed an arms embargo, even as the Soviets were arming the Communists to the teeth, with weapons arriving by the wagonload.

The key to success is tactics, or what I call unrestricted warfare — they were ruthless, and did not hesitate to use villagers as shields, place barrier troops behind the soldiers, or starve entire cities into surrender.

This is literally what happens in Changchun [in north eastern China]. Lin Biao orders that city to be starved into surrender, as he imposes a blockade for eight months, with trenches four meters deep and a sentry every fifty meters. 160,000 civilians die of hunger and disease.

Zhang Zhenglong — a lieutenant in the PLA — says that the devastation was roughly the same as in Hiroshima, except that it took eight months instead of a few seconds.

If you are the military commander in charge of a city like Beijing, and you see what has been done to Changchun, are you still willing to fight?

The answer, in many cases, is no.

Do you think this pre-1949 period left elements in the Party’s “DNA” that still shape how the CCP governs today?

Yes, absolutely.

There is widespread paranoia and the constant fear of being surrounded by the imperialist camp. That’s true throughout the Civil War and today.

There are the purges within the party and the army. We had them in Yan’an, and we’ve recently seen them again. When seven members of the Central Military Commission are reduced to a mere two, and one of these is Xi Jinping, you learn something about paranoia and lack of trust.

Then there is the Orwellian doublespeak — “New Democracy” in Yan’an, the “people’s democratic dictatorship” today, not to mention war as peace (“peaceful reunification”), or propaganda as truth (“all news must be good news”).

There is also the willingness to make alliances with anyone and discard them once they are no longer useful. And most of all, the absolute conviction that having shed so much blood to obtain absolute power, you must maintain power at all costs.

You’re probably the bestselling writer on China’s modern history. However, some academic historians have criticised your work as foregrounding atrocity or approaching the archive with a predetermined agenda. How does that relate to your research process?

There’s a book I recommend by Michael Billig called Learn to Write Badly: How to Succeed in the Social Sciences.

He argues that much of academia is marred by bad language and pretentious jargon, but also by something much deeper. He says academics need two approaches, and tells the old joke that every believer needs two churches, the one you go to and the one you denounce.

He also says that for every conference you attend and for every friend you make in the field, the more of your independence you lose.

I have, so to speak, become liberated from the church. I no longer feel that I have to quote somebody because that person agrees with me, or not quote a book because its author disagrees with me.

My compass, moral and otherwise, comes from the primary sources. When the questions raised by a primary source lead me to appreciate a secondary source, I do so regardless of whether or not its author is left, centre, right, or whoever. I couldn’t care less.

I am not going to silence what I discover in order not to upset certain readers. My commitment is not to a church or a club or a field or a friend, but to the truth.

Jonathan Chatwin is a writer and teacher focused on China. He is the author of Long Peace Street (2019), tracing the history of a single street in Beijing, and The Southern Tour (2024), an account of Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 tour of southern China to boost the nation’s private economy.