It was past dusk when Sinovac’s special shareholders meeting kicked off in St. John’s, Antigua on July 8. At a law firm tucked into a back alley, a short drive away from the country’s High Court building, a throng of lawyers prepared to square off in the latest round of a years-long fight for control of China’s flagship COVID-19 vaccine maker.

Several tumultuous weeks of legal proceedings had built to this point. The two factions competing for control of Nasdaq-listed Sinovac had been locked in negotiations with an Antiguan judge over which shares could be counted at the meeting.

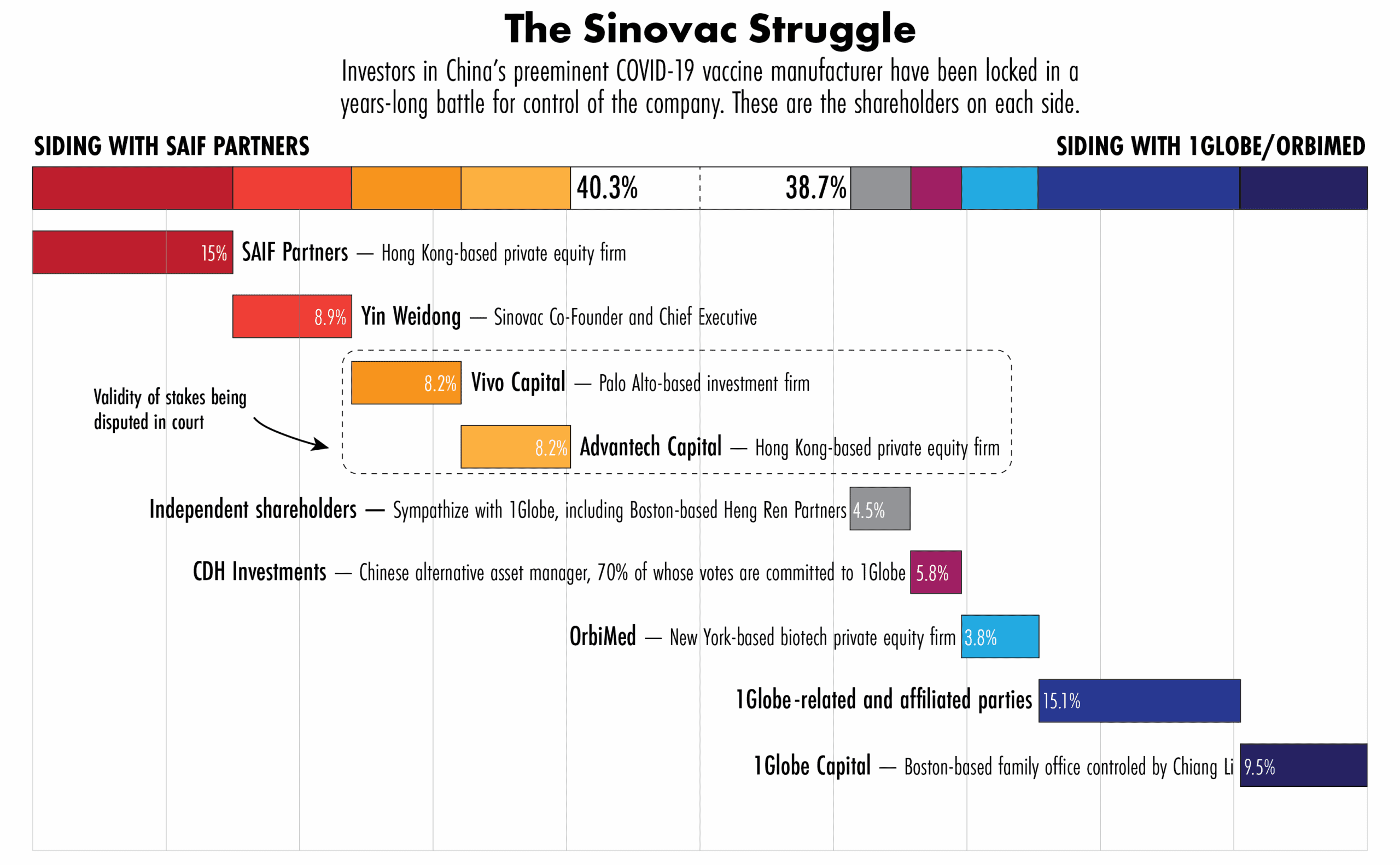

On one side was a group including Sinovac’s board chair, Jiaqiang Li, who goes by Chiang and holds his stake through 1Globe Capital. On the other was a rival group, led by Hong Kong private equity firm SAIF Partners, that also included Sinovac’s co-founder and chief executive, Yin Weidong.

The special shareholder meeting had been called by SAIF, which was pressing for the election of a new board. But the two sides disagreed over which shareholders could vote.

In 2018, the management team and SAIF had brought two new investors into Sinovac, after uncovering what they alleged was a plan by an external consortium, supported by dissident shareholders including 1Globe, to replace the board. 1Globe denies it was part of that plan. The Privy Council, the British Commonwealth’s highest court, subsequently designated the SAIF-supported board “imposters,” handing authority over Sinovac to a new board chaired by 1Globe’s Li and throwing the validity of the 2018 investors’ stakes into doubt.

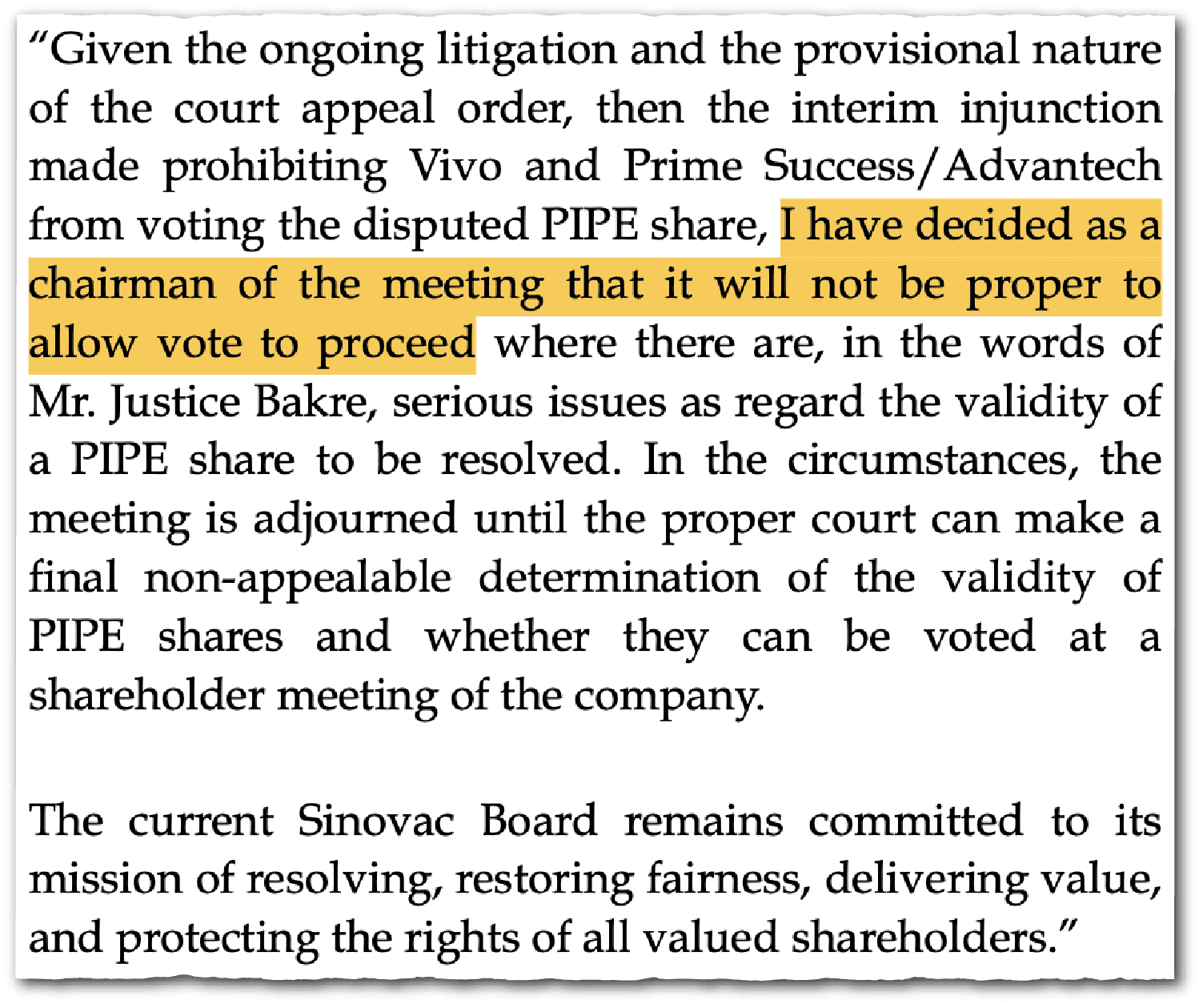

A day earlier, the judge had barred the two new investors from voting. But just hours before the meeting was set to begin, lawyers for one of the investors persuaded a different appeals court judge to pause the order. Amid the uncertainty, the board’s lawyers advised Li to adjourn the meeting.

“Given the ongoing litigation and the provisional nature of the court appeal order… I have decided as a chairman of the meeting that it will not be proper to allow vote to proceed,” Li said remotely from his office in Boston.

Li did not know that his rivals had another move planned. After he adjourned the meeting, the board’s lawyers in Antigua witnessed six people depart their law office and board a minibus, which later parked on an adjacent street. According to court documents, while in the minibus the six people called a Sinovac director and reconvened the shareholders’ meeting without the other attendees’ knowledge, including Li and the independent inspector of elections. Declaring a majority, they announced that their board slate had won the election.

Li and his supporters dismissed the new board as a “sham,” but the SAIF coalition had one advantage: access to Sinovac’s passwords, letting them file official notices and claim legitimacy with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

On July 10, the SAIF-led consortium used the codes to file notice with the SEC, claiming they had held a board meeting and elected SAIF managing partner Andrew Yan as Sinovac’s new chair.

“This marks the beginning of a new era for the Company — one grounded in sound governance, operational excellence, and global ambition,” Yan, the new chairman, said about the newly elected board. “I am confident that, together with management, we will lead SINOVAC into a stronger, more sustainable future.”

Yan’s statement proved premature: the two sides are now back in court fighting over the legitimacy of the July proceedings.

The SEC has also blocked both groups from uploading filings without its prior approval after the Sinovac board chaired by Li raised objections, according to people with knowledge of the matter. Pending litigation could take months, if not years, further prolonging what has been an ugly and destructive spat for control of a would-be national champion.

“The imposter board used the appeals court ruling to declare victory, despite the shares being ineligible from voting and the election results not being counted. Yet they filed with the SEC as if they had won and were in charge,” says Peter Halesworth. Halesworth, founder of Boston-based investing firm Heng Ren Partners, is a longtime independent Sinovac investor who supported the 1Globe-led board in the election contest in July.

Neither Sinovac nor the SAIF-led investor coalition responded to The Wire China’s multiple requests for comment. But in a press release from the first meeting Sinovac announced it was intent on restoring “stable operations” at the company.

TEN BILLION REASONS TO FIGHT

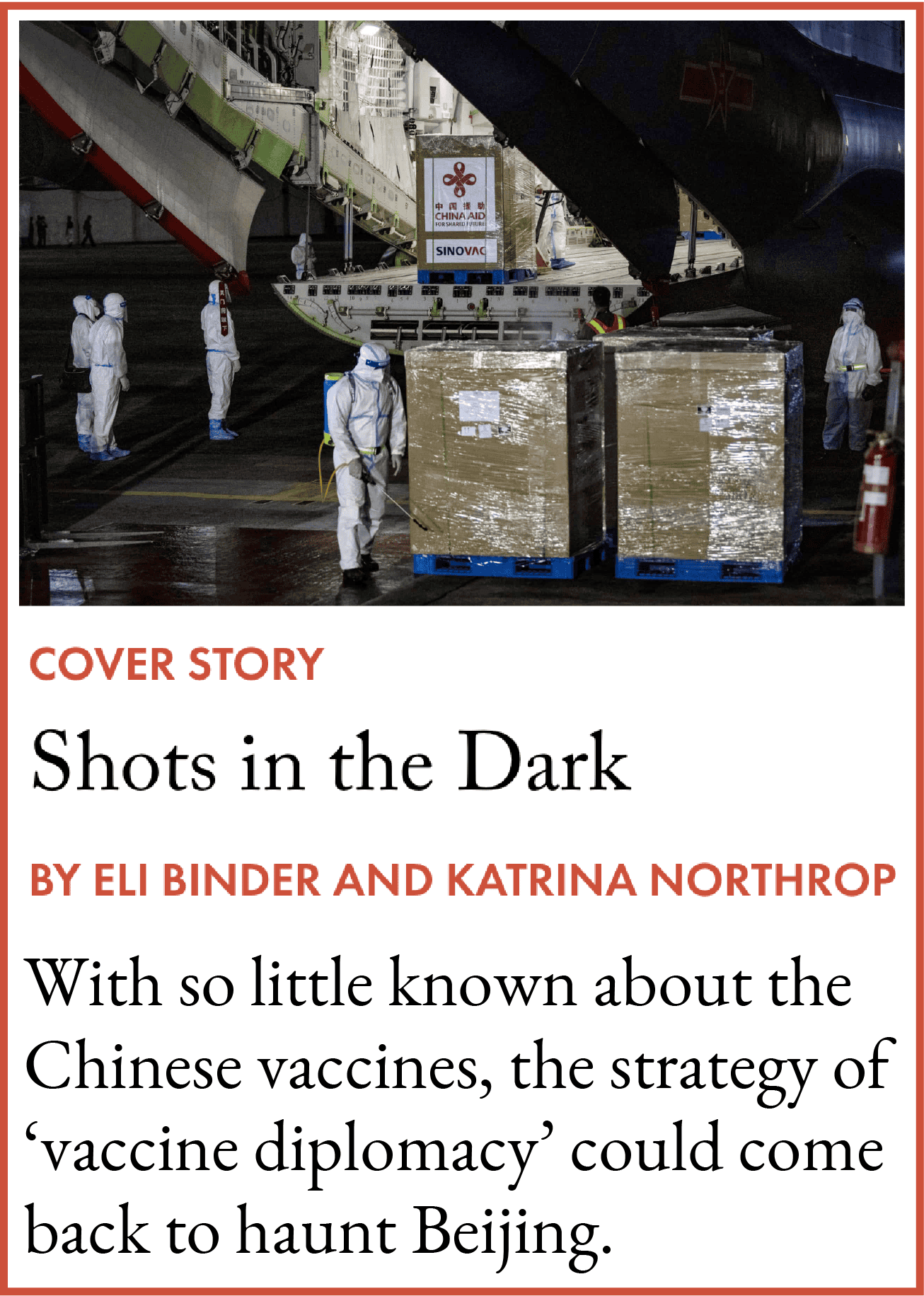

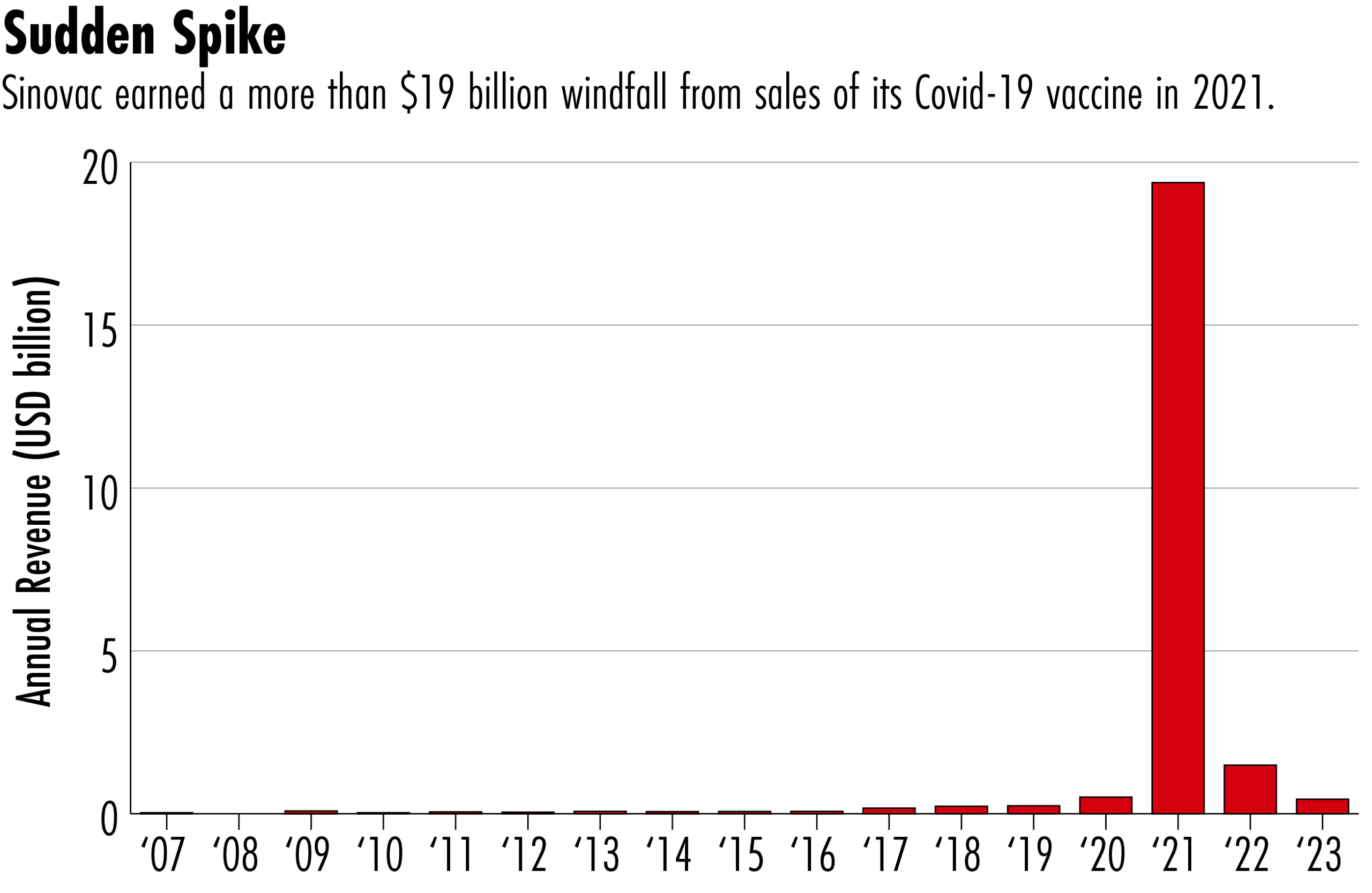

The battle for Sinovac is so bitter because the stakes are so high: insiders estimate the company has accumulated more than $10 billion in cash reserves. That windfall was amassed during the pandemic, when Sinovac quickly developed a successful and low-cost vaccine and emerged as one of China’s leading producers, delivering 2.9 billion doses to more than 60 countries by the end of 2022.

But even as Sinovac, listed on the Nasdaq since 2006, emerged as one of China’s most important and recognized companies, behind the scenes its biggest shareholders were locked in an increasingly intractable conflict.

Investors have been prevented from reaping the rewards of their early bets. That is because Sinovac’s shares have been frozen on Nasdaq since 2019 — the longest trading suspension in the exchange’s history.

“We missed out on this huge bonanza [during] peak-COVID when our peer stocks like Moderna and BioNTech went to the moon,” says Halesworth.

Before the trading halt, Sinovac had a market capitalization of $460 million, a small fraction of the $19.4 billion in sales the firm reported in 2021 alone. “The company is saying nothing about what’s next,” he adds. “More transparency is needed, especially on promised and future dividends.”

The trading suspension traces back to a 2017 privatisation dispute and began when the SAIF-led consortium deployed a nuclear ‘poison pill’ to block what it called a plot to replace Sinovac’s board. The conflict has featured competing factions claiming control of the company, a physical brawl between investors at Sinovac’s Beijing offices, and numerous lawsuits.

The long-awaited Antigua rulings this year were supposed to resolve this original dispute. Instead, they deepened the chaos, with both sides now claiming their own boards and control of the company. Meanwhile, Sinovac’s Covid-era rebirth as China’s vaccine champion has not only raised the financial stakes of the dispute, but has also turned the shareholder fight into a U.S.-China proxy conflict.

Although many of the investment firms on both sides of the battle are managed by Chinese nationals, some Chinese media outlets have framed the conflict as between a nationalist defender fighting greedy American investors. As one Chinese article put it: “Chinese take the shots, Americans count the money.”

It’s a real test case about how investable Chinese companies are and if they can just turn their backs on global investors whenever they feel it’s in their interests.

Peter Halesworth founder of Boston-based investing firm Heng Ren Partners and longtime independent Sinovac investor

Investors like Li and Halesworth counter that the conflict is about upholding corporate governance rules and equal treatment of minority shareholders. If SAIF succeeds, Halesworth says, it should be taken as a sign that Chinese companies, even ones listed on American exchanges, do not need to play by U.S. rules.

“It’s a real test case about how investable Chinese companies are and if they can just turn their backs on global investors whenever they feel it’s in their interests,” he said.

CONQUERING NATURE

Despite the feud, both sides agree on one surprising point: Yin Weidong, the company’s 61 year-old founder and China-based CEO, should remain CEO.

In July 1976, Yin was 12 years old when his hometown of Tangshan in northern China was levelled by one of the deadliest earthquakes in recorded history. Yin survived, but many of his classmates did not.

One of his teachers later delivered a lecture about the many times in Chinese folklore and history that man prevailed against nature, echoing Mao Zedong’s ‘Man Must Conquer Nature’ slogan. Yin was inspired, and dedicated himself to science to regain a sense of control over the natural world.

Yin started his career as a field epidemiologist shortly after finishing a vocational school degree in medicine in 1982. He became the first doctor in China to isolate the hepatitis A virus, and went on to develop a widely used diagnostic test. In 1999, he developed China’s first homegrown hepatitis A vaccine.

Yin founded Sinovac in Beijing two years later. Shortly after Sinovac’s founding, the SARS epidemic broke out in southern China and the company raced to develop a vaccine. Sinovac developed a promising candidate, and became the first company in the world to begin trials. But the vaccine did not prove necessary. By 2004, the deadly virus had burned itself out.

But to some investors, Sinovac’s handling of SARS signaled potential.

“A vaccine maker in an epidemic‑prone, massive market was a compelling ‘what if,’” says Halesworth, who has self-published a book on the Sinovac saga.

Sinovac, likewise, wanted access to foreign capital. But rather than pursue a protracted U.S. IPO process, the company took a shortcut via a ‘reverse-merger’ process. It went public by taking over Net-Force, a dormant Antigua-registered shell company.

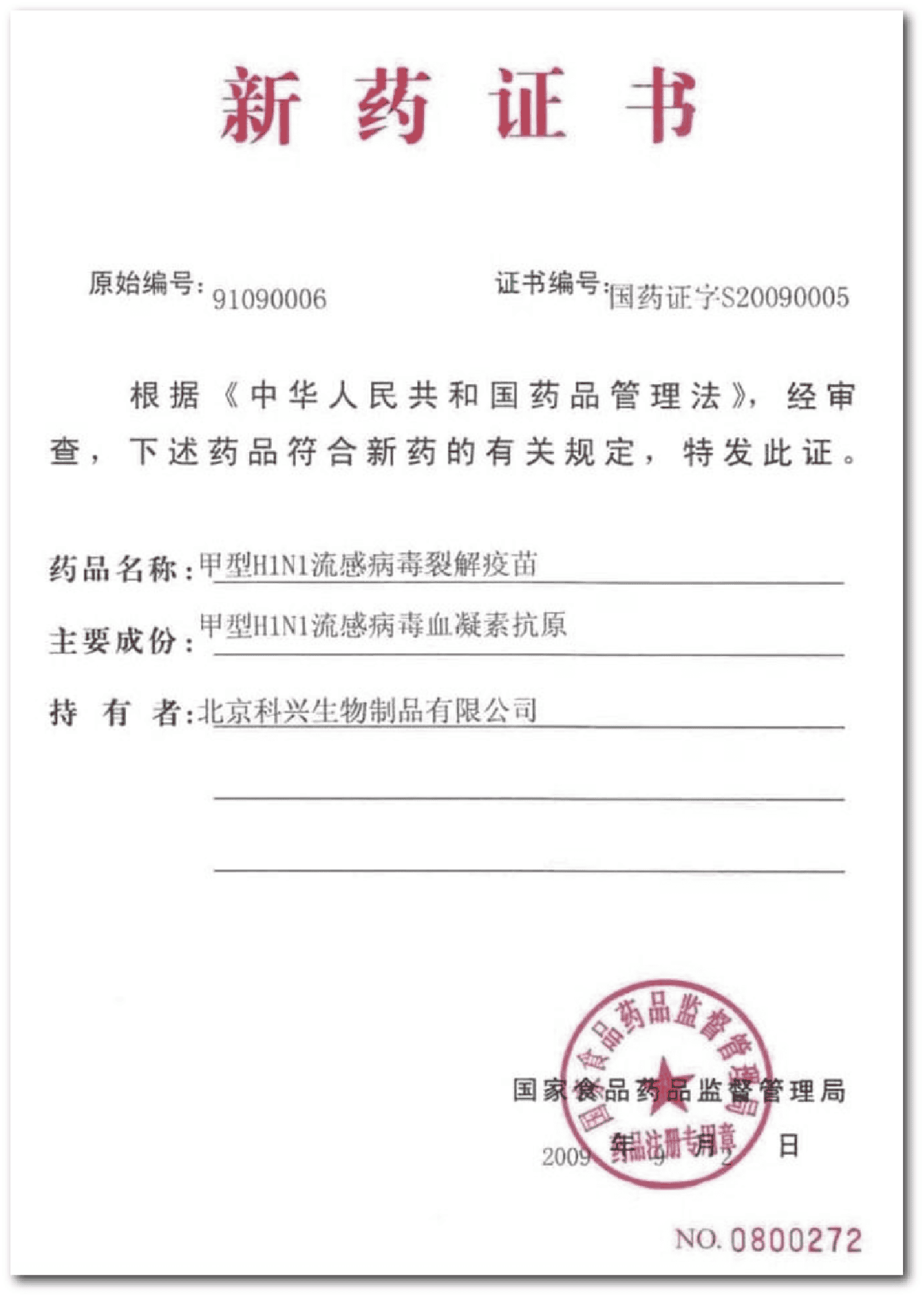

Sinovac began trading on Nasdaq in 2006, and spent the late 2000s and early 2010s developing and commercializing vaccines for diseases such as influenza, Japanese Encephalitis and swine flu. Over ten years, revenues increased five-fold, from $15 million in 2006 to $73 million in 2016.

It was around this time that many of Sinovac’s largest current shareholders started acquiring their stakes in the company: SAIF acquired a 10.1 percent stake in 2010, the same year that 1Globe made its first investment. OrbiMed, a New York private equity firm focused on healthcare, acquired 4.6 percent.

But Sinovac’s success was accompanied by controversy. In 2016, Yin was embroiled in the corruption trial of Yin Hongzhang (no relation), an official at the China Food and Drug Administration.

At the trial, Yin, of Sinovac, admitted to paying $77,000 worth of bribes between 2002 and 2011 to Yin, the official, in exchange for expediting Sinovac’s drug approvals.

The official was later sentenced to 10 years in prison. But Sinovac’s Yin was not charged, and remained CEO. In cases involving allegedly corrupt Chinese officials, it is not unusual for someone accused of facilitating a bribe to be named in the proceedings but not be charged with wrongdoing.

Yin claimed in court that he could not refuse the official’s demands. The U.S. SEC and Department of Justice also investigated the bribery allegations involving Yin but ultimately closed the cases without filing charges. Sinovac did not respond to The Wire’s requests for comment on the case.

Sinovac’s investors faced another challenge: a languishing share price. They believed the company’s true value was far above the $5 per share it traded at on Nasdaq.

Other U.S.-listed Chinese companies felt the same way. In the mid-2010s, many Chinese firms felt undervalued in the U.S. and weighed down by politics while China’s stock market boomed. Relisting in China became an increasingly attractive option.

In 2015 WuXi Pharmatech, listed on the New York Stock Exchange, went private in a $3.3 billion deal; it re-listed in Hong Kong three years later, achieving a valuation of $10.2 billion. Another NYSE-listed firm, Qihoo 360, did a $9.3 billion privatisation deal in 2016. When it re-listed in Shanghai two years later, it was valued at more than $60 billion.

In February 2016, Sinovac announced its own privatization and re-listing plan. “It was a simple arbitrage,” says one industry insider who has followed the Sinovac saga.

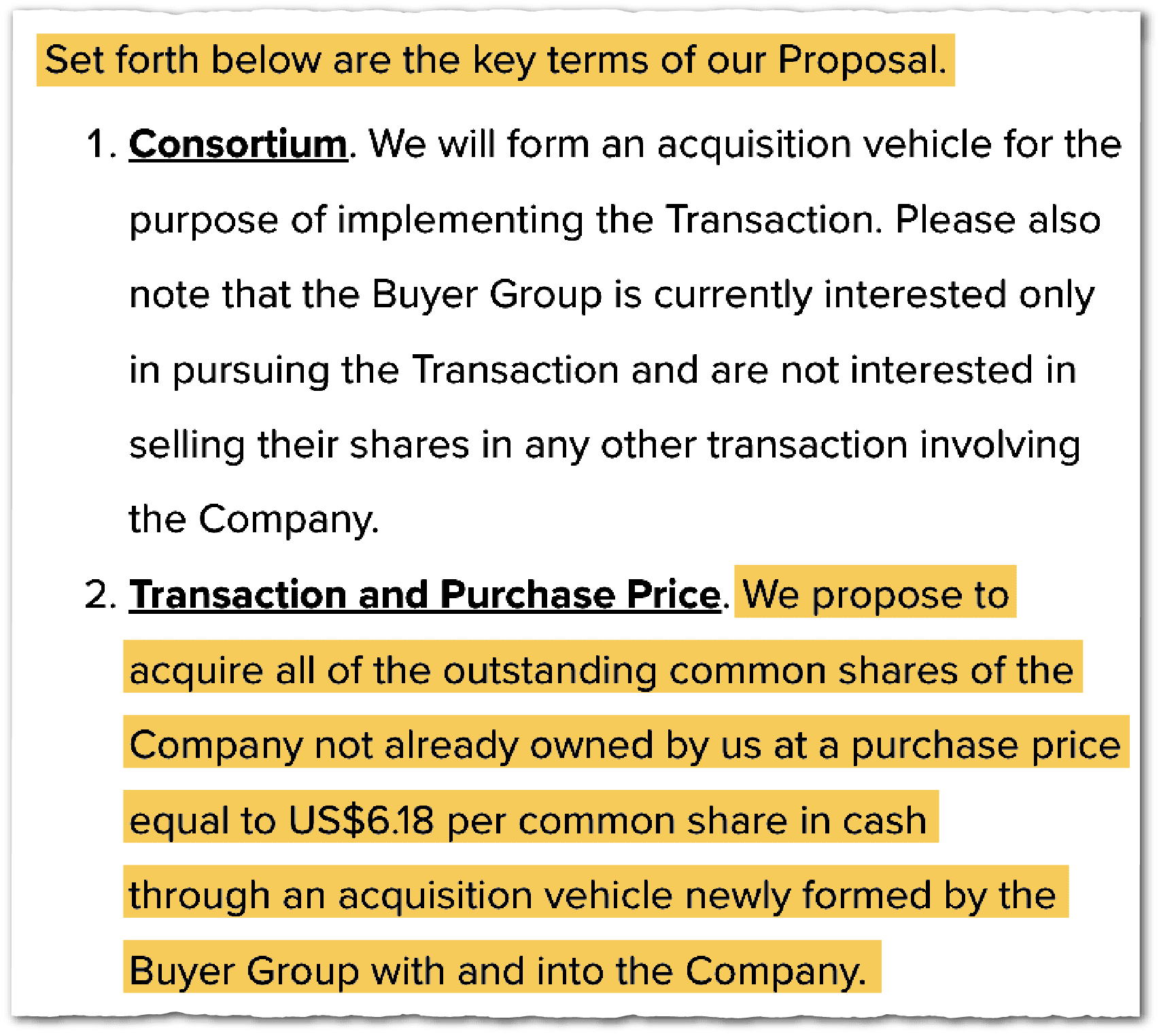

Some shareholders were not impressed by its offer to buy them out for $6.18 per share. That was 23 percent above the undisturbed share price, which valued the company at $345 million, but it was also nearly 40 percent below the stock’s all time high of $9.95 per share.

A competing offer emerged from an unlikely source: a consortium led by Yin’s longtime business partner and Sinovac co-founder Pan Aihua, which countered with an offer of $7 per share.

Pan, an adjunct professor at Peking University and vice-chair of the prestigious university’s biology department, had co-founded Sinovac with Yin in 2001 and previously served as the board chairman and legal representative of Sinovac’s China operating subsidiary. The two had been close, but Pan’s offer made clear the relationship had soured. At the same time, Pan had his own biotech firm, Sinobioway Group, and lined up some powerful backers to finance his counter offer, including state-owned giants CITIC and China International Capital Corporation (CICC).

Li, a doctor by training who is an adjunct faculty member at Harvard Medical School, first began investing in Sinovac in 2010 and became its largest shareholder in 2016. In the dispute between Yin and Pan, Li initially tried to mediate. After that failed, he ultimately preferred Pan’s offer.

On the Chinese side, there is national pride — they don’t want to be taken over. On the investor side, once you list shares on a public exchange, you open yourself to vulnerabilities, including takeovers. Companies can’t change the rules mid-game when they don’t like the outcome.

Wei Jiang, a corporate finance professor at Emory University

A pivotal moment came at Sinovac’s annual general meeting in February 2018, when shareholders voted on a proposal to elect a new board of directors put forward by OrbiMed, the New York biotech investor. 1Globe voted in favor of the proposal. The votes were tabulated and showed a majority had voted for the new board. But the election overseer declined to declare the results, stating she needed to confirm their validity with Sinovac’s counsel.

Tensions escalated from there. On April 17, 2018, Pan, alongside dozens of unidentified individuals, “forcibly entered” the offices of Sinovac’s Beijing subsidiary in an attempt to seize the company’s official seal and other legal documents, according to an SEC filing. As Sinovac Beijing’s legal representative, Pan had entrusted the company’s corporate seal to Yin when their relationship had been more cordial, a source close to the matter tells The Wire. The break-in happened because Pan wanted to retrieve the seal, which in China endows the bearer with final legal authority over a business.

The two sides scuffled outside Sinovac Beijing’s offices, according to court filings.

Sinovac alleged that, during the fracas, it came into possession of documents showing that Sinobioway and 1Globe had worked together to replace the board at the February AGM, and accused 1Globe of contravening SEC rules. 1Globe denies the allegation.

An SEC investigation found that “1Globe Capital and Li had decided to participate in an activist plan… and instruct their representatives to attend the annual meeting and vote their shares for [a new board of directors].” Li and 1Globe agreed to settle the charges and paid $290,000 for failing to fully disclose the extent of Li and his associates’ holdings as of January 2018. The settlement did not require 1Globe to admit or deny the findings.

A spokesperson for 1Globe says that while 1Globe voted for the new board slate at the 2018 meeting, Li did not organize the campaign for a new board or select its members.

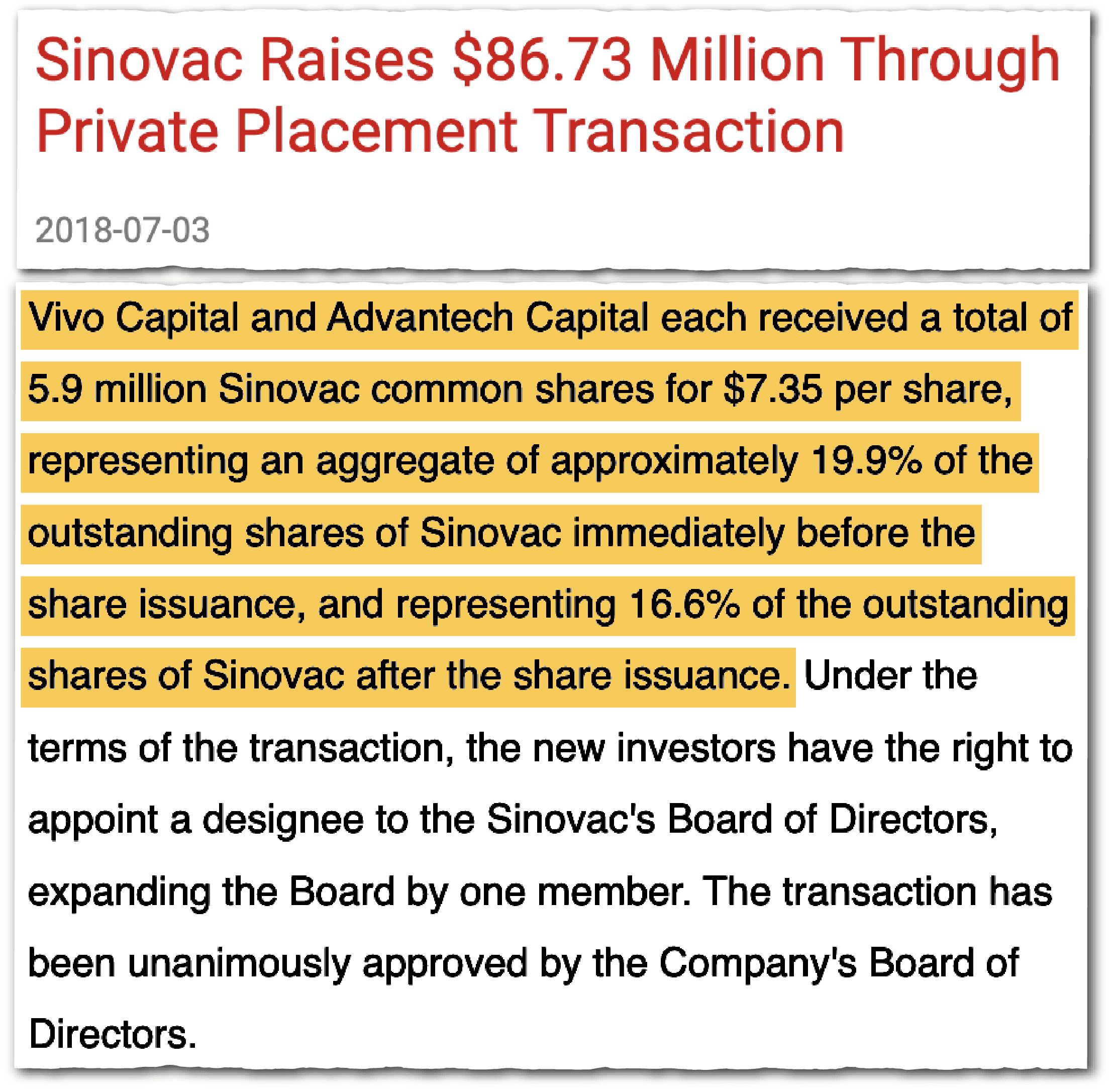

That July, Sinovac brought in two new investors whose stakes are now disputed: Vivo Capital, a Palo Alto-based private equity firm, and Advantech Capital, an investment firm spun out of New Horizon Capital.

New Horizon is a private equity firm founded in 2016 by Winston Wen, the son of Wen Jiabao, the former Chinese premier. The firm’s managing partner is Yu Jianming, a college classmate of Winston’s. The private transaction increased the SAIF side’s voting power from 29.9 percent to 40.7 percent.

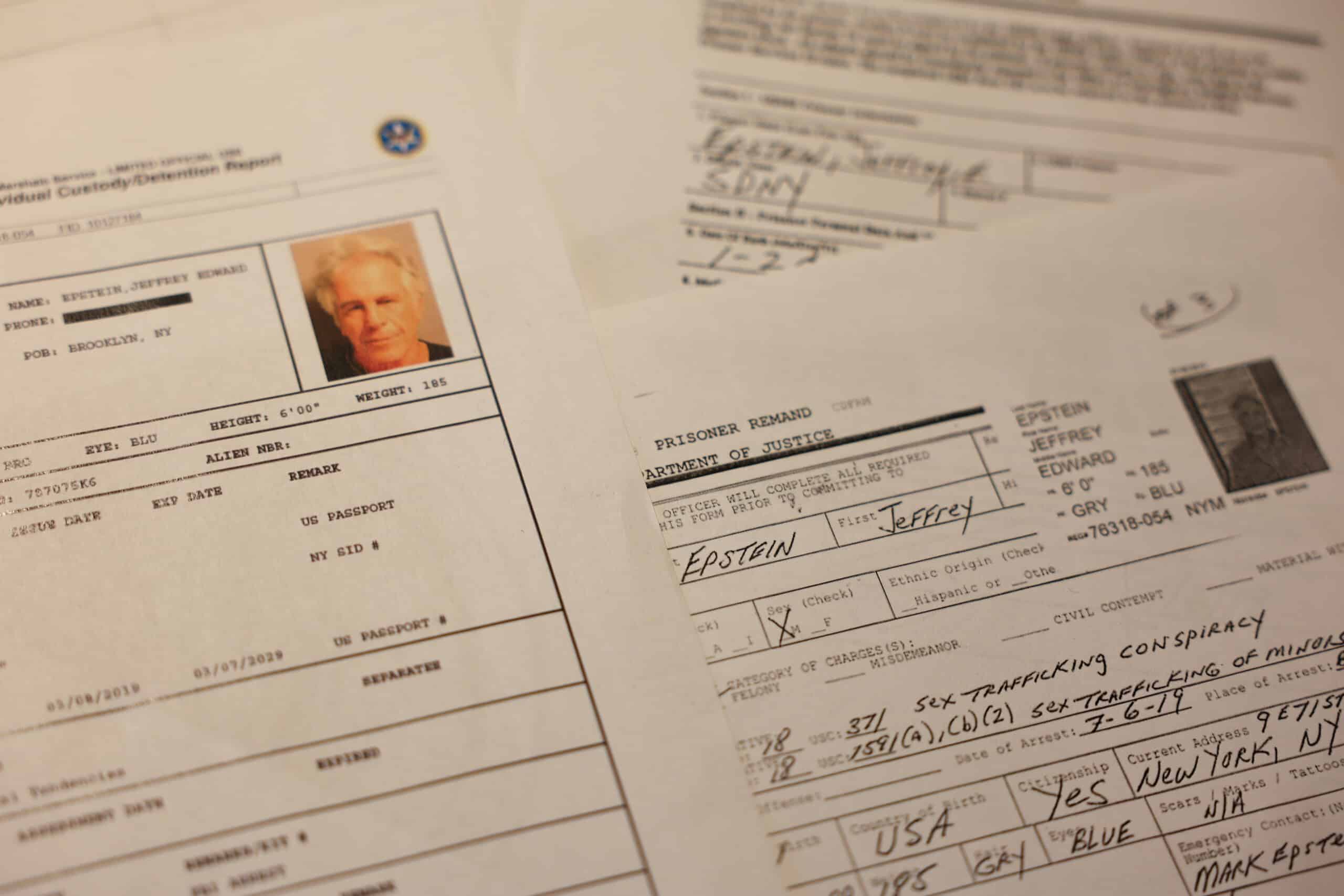

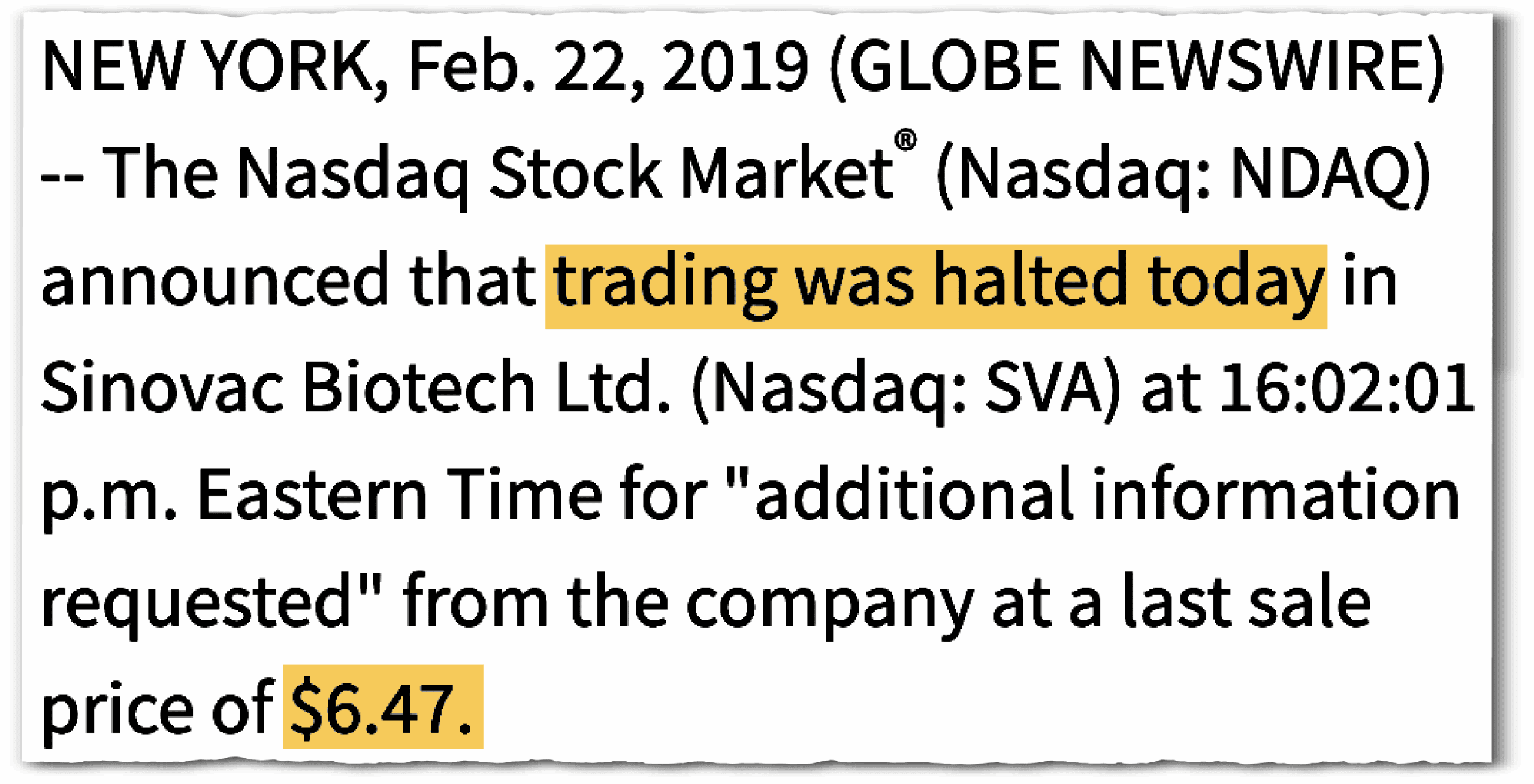

Despite having a stronger hand, SAIF still faced the takeover threat. On February 22, 2019, Sinovac triggered its poison pill, issuing 28 million shares to other holders after alleging 1Globe and OrbiMed coordinated with allies to acquire more than 15 percent of the firm’s shares.

Nasdaq halted trading of Sinovac’s stock that day, and courts in Antigua and Delaware later issued rulings freezing the poison pill plan pending further litigation.

The end result was a stalemate. Six years later, Nasdaq’s 2019 trading halt remains in place as the two sides continue to battle in courts.

COVID HERO

Sinovac was an unlikely choice to be China’s leading COVID vaccine maker. The company was from the private sector and tiny compared to Sinopharm Group, the partially state-owned pharmaceutical giant that developed China’s other main COVID vaccine. Sinovac also relied on an old approach — developing an inactivated vaccine using a killed-off form of the virus — while peers like BioNTech and Moderna built entirely new mRNA platforms.

The company’s edge lay in its SARS vaccine candidate, developed back in 2003. And Sinovac mobilized quickly when COVID-19 first struck: Yin dispatched scientists to begin developing a vaccine in January 2020, the same month that the outbreak was confirmed by Chinese authorities and its epicenter, Wuhan, locked down. By April it had begun early trials and was selected by Beijing as a key COVID vaccine supplier a few months later.

But even as vaccine development took center stage, Sinovac’s board worked behind the scenes to edge 1Globe, OrbiMed and its affiliates out of the company’s vaccine windfall and bring in new investors.

In May 2020, a month after Sinovac announced it had commenced human clinical trials, the company struck an agreement with Vivo and Advantech, the two investors also involved in the 2018 deal.

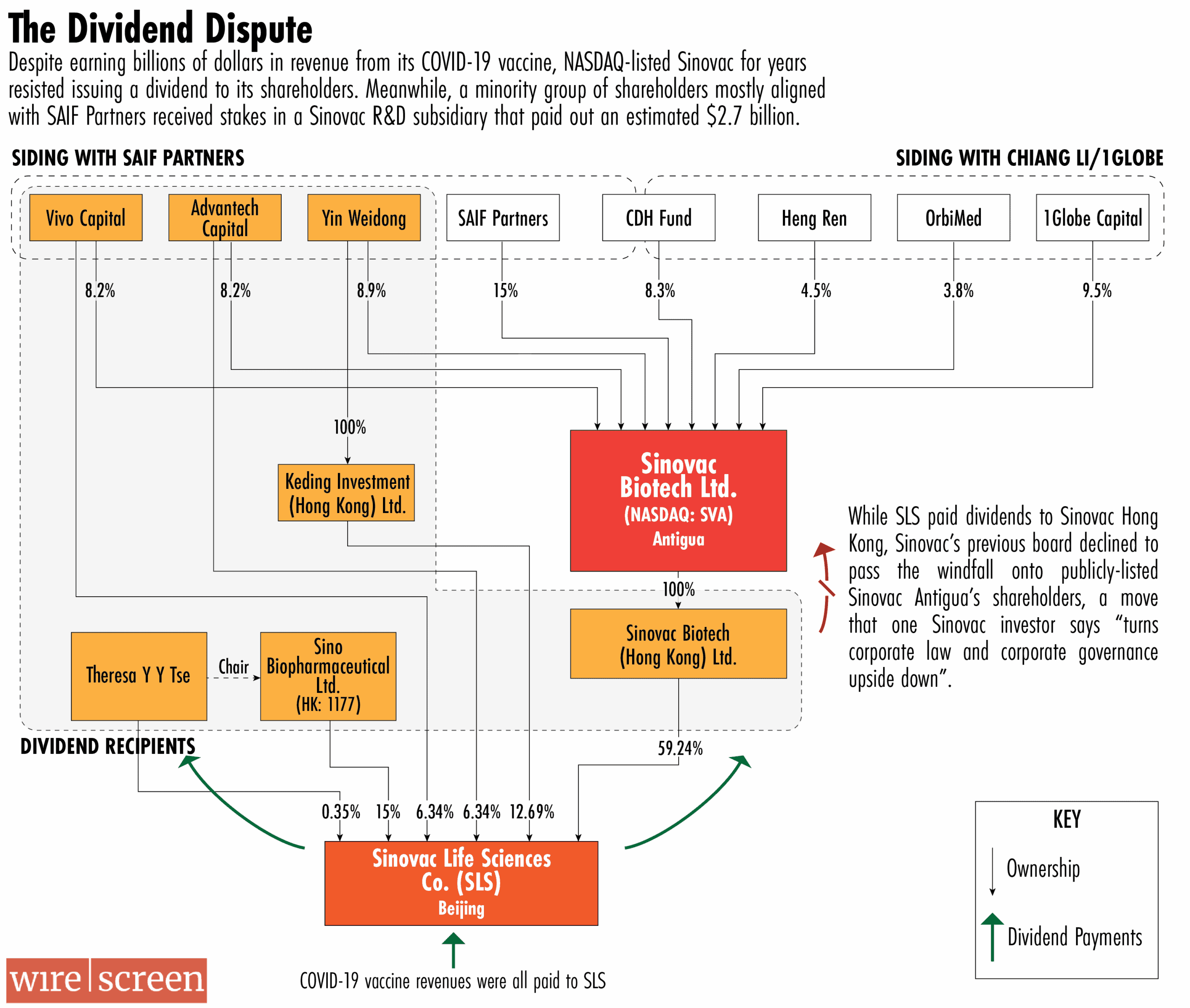

Vivo and Advantech extended a $15 million loan — which could be converted into shares — to Sinovac’s R&D subsidiary, Sinovac Life Sciences Co. (SLS). If converted, Vivo and Advantech would end up with a 15 per cent stake in SLS.

The following month, Chinese authorities approved Sinovac’s CoronaVac vaccine for emergency use in China.

Then, in December 2020, SLS reached another agreement with Sino Bio Pharmaceutical Ltd (also known as Sino Biopharm), under which the Hong Kong-listed Chinese pharmaceutical firm acquired a 15 percent stake in SLS for $515 million.

As Covid raced around the world in the seven months between the Vivo-Advantech convertible loan deal and Sino Biopharm’s stake purchase, SLS’s valuation soared more than 34 times.

It was an unusual transaction. A Sino Biopharm filing stated the investment was intended to “fund the further development, capacity expansion and production of CoronaVac,” capitalizing on Sino Biopharm’s “strong industrialization capabilities.” But Sino Biopharm had little experience with vaccine manufacturing. According to its annual report, the deal “mark[ed] Sino Biopharm’s foray into vaccine R&D and production.”

Nor was Sino Biopharm any ordinary investor. It had a distinguished lineage. Sino Biopharm is controlled by CP Group, a Thai conglomerate that was one of the first foreign investors in China after Deng Xiaoping launched the reform and opening era.

Run by the Chearavanont family, the second wealthiest family in Asia, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, CP Group has over the years acquired substantial stakes in some of China’s largest companies, including the state conglomerate CITIC and Ping An Insurance.

Sino Biopharm’s executive chairwoman is Theresa Y.Y. Tse, a grand-niece of CP’s patriarch, Dhanin Chearavanont. Data from WireScreen shows that Tse also personally acquired a 0.35 percent stake in SLS as part of the transaction.

Sino Biopharm did not respond to requests for comment.

In June 2021, the World Health Organization approved CoronaVac for emergency use worldwide. Its low cost quickly made it one of the most widely distributed shots in the world.

Sinovac in turn reaped a historic windfall: at least $11 billion from sales of the vaccine alone. Most of its investors, however, were unable to share in those gains. While stocks in its peer vaccine makers like Moderna and BioNTech soared to record highs of around $450 a share, because of the trading suspension, Sinovac’s shares remained suspended at $6.47, the price its stock was worth in 2019.

Moreover, Sinovac declared in its 2023 annual report that it had no “present plan to pay any cash dividends on [Sinovac’s] shares in the foreseeable future.” It added that it intended to “retain most, if not all, of our available funds and any future earnings to operate and expand our business.”

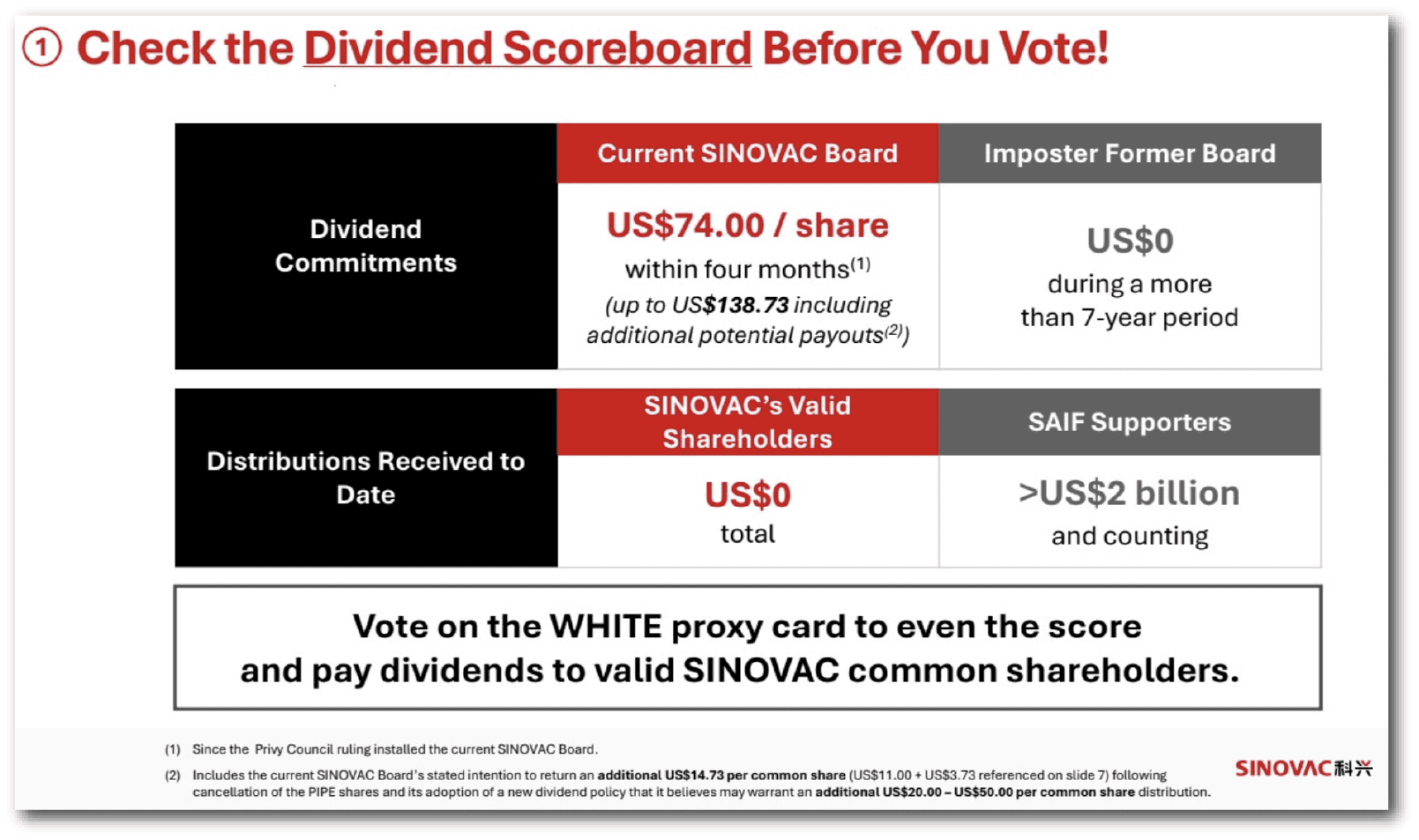

Meanwhile, some of SLS’s shareholders benefitted. A group including Sino Biopharm, Vivo, Advantech, Yin and Tse received an estimated $2.7 billion in dividends between 2021 and the first half of 2024, according to records reviewed by The Wire. Investors in Nasdaq-listed Sinovac did not receive any corresponding dividends, despite their 59 percent share being worth an estimated $4 billion.

Only Sino Biopharm has publicly reported receiving dividends. Its annual reports show it earned roughly $279 million from SLS dividends between 2024 and the first half of 2025.

“Our interests as shareholders were sacrificed,” says Halesworth. “Billions of dollars reportedly were funneled from the subsidiary to their minority shareholders, instead of funneled up to the parent and its shareholders. That just turns corporate law and corporate governance upside down.”

LI STEPS UP

In February 2024, Pan was sentenced by a Chinese court to 13 years in jail for embezzlement, related to another company he owned called Weiming Pharmaceutical.

At the same time, Li stepped up to fund the activist investors’ legal battle. Courts began ruling in Li’s favor.

On January 15, 2025, the UK Privy Council, the highest appeals court for Commonwealth countries such as Antigua, ruled that the 2018 board election was, in fact, valid. In the judgement, the justices called the board backed by SAIF Partners and Yin an “imposter board,” ruling they had no right to issue the 2019 poison pill.

For Li’s team, it was a decisive victory. A new board was reconstituted with Li as chair. Sven Borho, founder and managing partner at OrbiMed, was appointed audit chair. The ruling also bolstered the new board’s claim that the old board’s deals with Vivo and Advantech, which gave them stakes in Sinovac, were illegitimate.

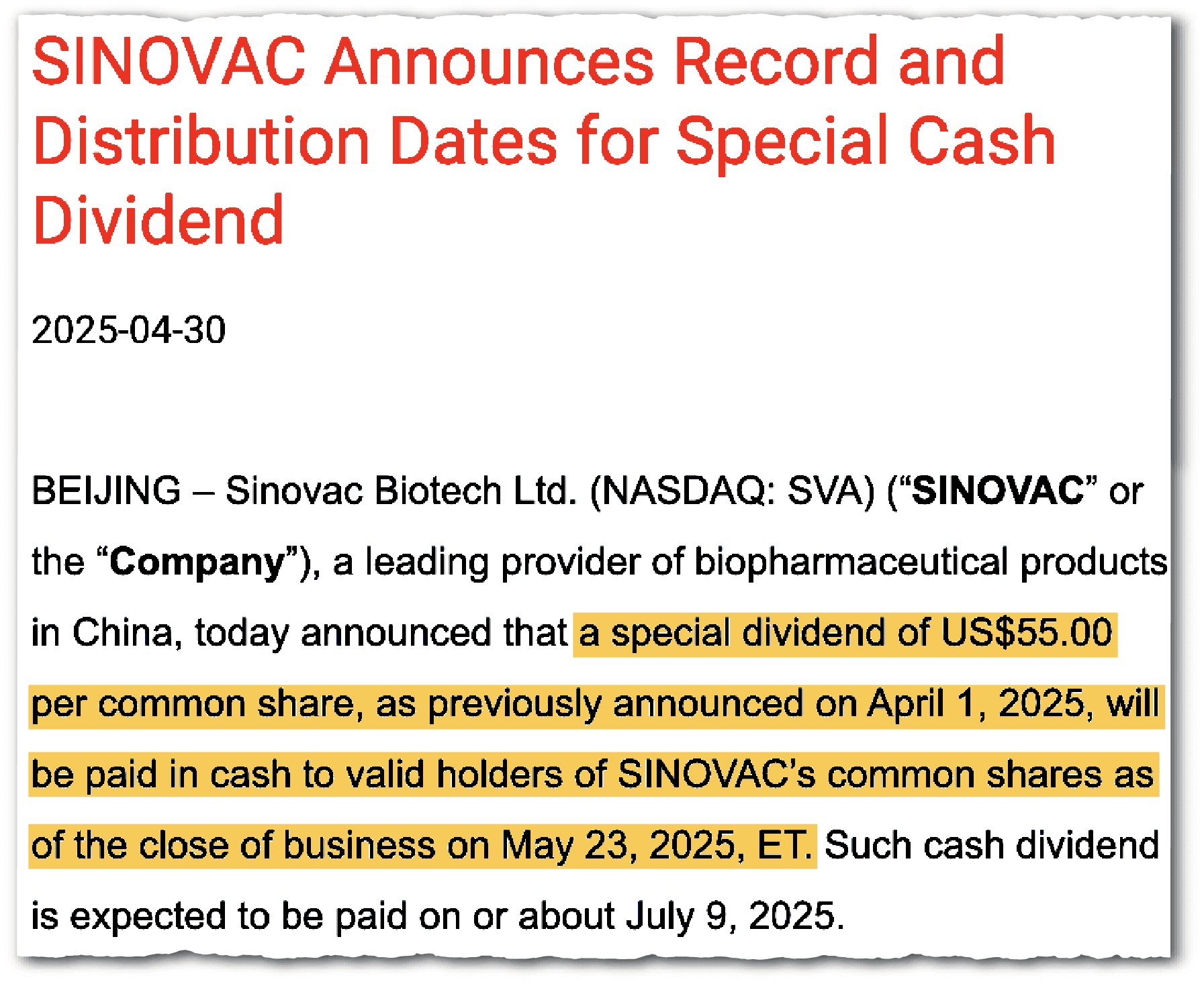

Shortly after taking over as chairman of the new board, Li announced a new dividend that would pay out $55 per share to Sinovac shareholders. This amounted to a payout of nearly $4 billion and was distributed in July to all shareholders except Vivo and Advantech, whose $649 million portion is being held in escrow pending the decision on the validity of the shares. The board chaired by Li argues this dividend was about “catching up” all the other Nasdaq investors, including Heng Ren, to the level of dividends already received by SLS’s shareholders.

A spokesperson for 1Globe said the dividends were paid out of cash reserves accumulated from CoronaVac’s international sales.

Halesworth, from Heng Ren, welcomed the $55 payout but says the first dividend should just be the start. He adds that he agrees with SAIF’s estimate that the company can afford a total dividend payout of close to $140 a share.

The new board planned another $19 dividend for investors, worth about $1.5 billion, after the July 8th shareholder meeting, which was supposed to cement shareholder support.

But then SAIF’s representatives, while meeting in their minibus in Antigua, upended the board’s plan, leaving unresolved claims of two competing boards and deep uncertainty about the firm’s future.

SILVER LINING?

To some outside investors, the record-breaking stock suspension and drawn-out corporate brawl has tarnished everyone involved, while also distracting from the company’s longer term challenges.

“Sinovac has a massive cash horde, but one obscured by a suspended stock and uninspiring prospects,” says Brock Silvers, CIO of Kaiyuan Capital. “It hasn’t come close to replicating its earlier success.”

Sinovac announced in January 2024 that it ended production of its COVID-19 vaccine. Subsequent financial statements revealed that the firm has been developing a new rotavirus vaccine and has expanded into new markets such as Turkey and Brazil. But the company has revealed little else about its future or what it plans to with its pandemic profits.

To some, Sinovac’s saga is a cautionary tale for American investors about the risks of investing in U.S.-listed Chinese companies.

“It will have a chilling effect on both sides,” says Wei Jiang, a corporate finance professor at Emory University. “It may reduce Chinese firms’ appetite to list in the U.S. or Europe, and it may make U.S. exchanges more reluctant to host them.”

After seven years of fighting, Li and his team still believe they can turn Sinovac around from a cautionary China-U.S. tale to one that instead bridges the chasm between the world’s two most powerful nations.

Jiang adds that the fight over Sinovac reflects a deeper rift — not over geopolitics but, more simply, over how companies ought to be run. “I think both sides have legitimate feelings,” she says. “On the Chinese side, there is national pride — they don’t want to be taken over. On the investor side, once you list shares on a public exchange, you open yourself to vulnerabilities, including takeovers. Companies can’t change the rules mid-game when they don’t like the outcome.”

After seven years of fighting, Li and his team still believe they can turn Sinovac around from a cautionary China-U.S. tale to one that instead bridges the chasm between the world’s two most powerful nations. A spokesperson for 1Globe adds that even as they continue to fight in court, Sinovac’s board, under Li, and management, under Yin, are finding ways to cooperate on key matters, such as issuing the $4 billion dividend.

The board and management have also worked together on appointing a new auditor, after the previous one resigned in April. A source close to the board told The Wire that the appointment is imminent.

The board expects a favorable ruling in Antigua in the coming months. It then plans to push for Sinovac to resume trading on Nasdaq with the current Yin-led, China-based management team kept in place, while pursuing a dual listing in Hong Kong to tap into China’s hot market.

But all future plans for Sinovac now hinge on a pending court decision in Antigua. No date has been set for the ruling.

Grady McGregor is a freelance writer for The Wire China based in Washington, D.C. He was previously a staff writer at Fortune Magazine in Hong Kong, writing features on business, tech, and all things related to China. Before that, he had stints as a journalist and editor in Jordan, Lebanon, and North Dakota. @GradyMcGregor

Eliot Chen is a Toronto-based staff writer at The Wire. Previously, he was a researcher at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Human Rights Initiative and MacroPolo. @eliotcxchen