Few observers expected U.S.-China relations to improve significantly during the second Trump administration. The speed with which they have deteriorated, however, is surprising and concerning. Before President Donald Trump took office, after all, he invited Chinese President Xi Jinping to attend his inauguration and contended that the United States and China could enjoy more fruitful, wide-ranging cooperation. As recently as early March, the two leaders were reportedly entertaining a “birthday summit” in June (Trump was born on June 14, 1946; Xi, on June 15, 1953).

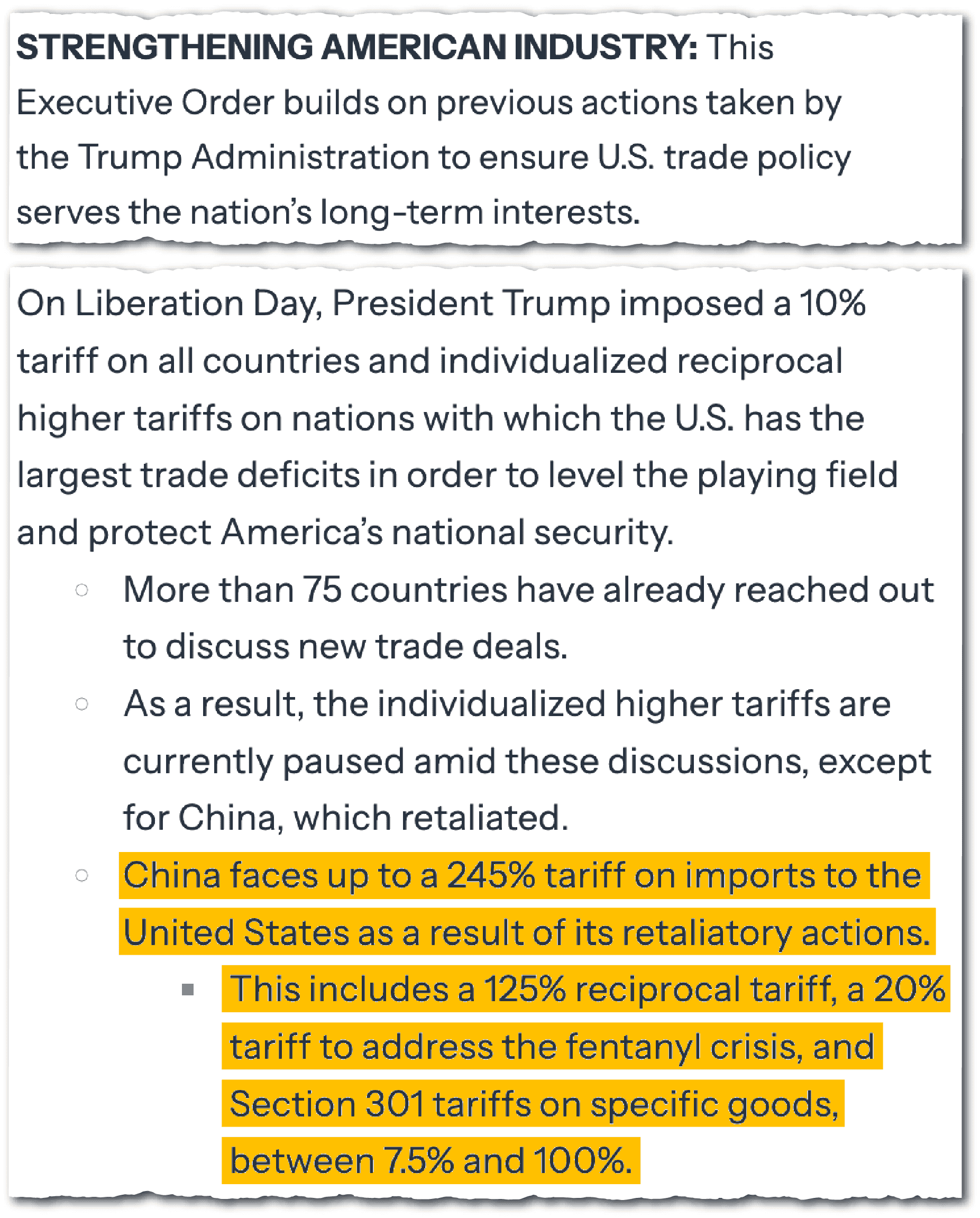

Trump’s April 2 “Liberation Day” tariffs and the ensuing cycle of economic retaliation between the United States and China have, however, initiated a new showdown between the world’s two leading powers just over three months into Trump’s second term, presaging a period of heightened volatility in bilateral relations.

On April 9, Trump announced a 90-day pause in reciprocal tariffs on most countries but pointedly raised the tariff rate on U.S. imports from China — a penalty that now stands at 245 percent for certain ones. Some of his advisors have retroactively attempted to render his April 2 and April 9 decisions as strategic masterstrokes that have isolated China. A less charitable, though more plausible, interpretation is that the former decision was an impetuous gambit; the latter, damage control.

The initial tariff announcement plunged global markets into turmoil — on April 4, for example, the S&P 500 registered its largest one-day decline since March 16, 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic was raging across the world — and elicited pushback from some of Trump’s most influential supporters, likely prompting him to appreciate that he could not fully control the consequences of what he had unleashed.

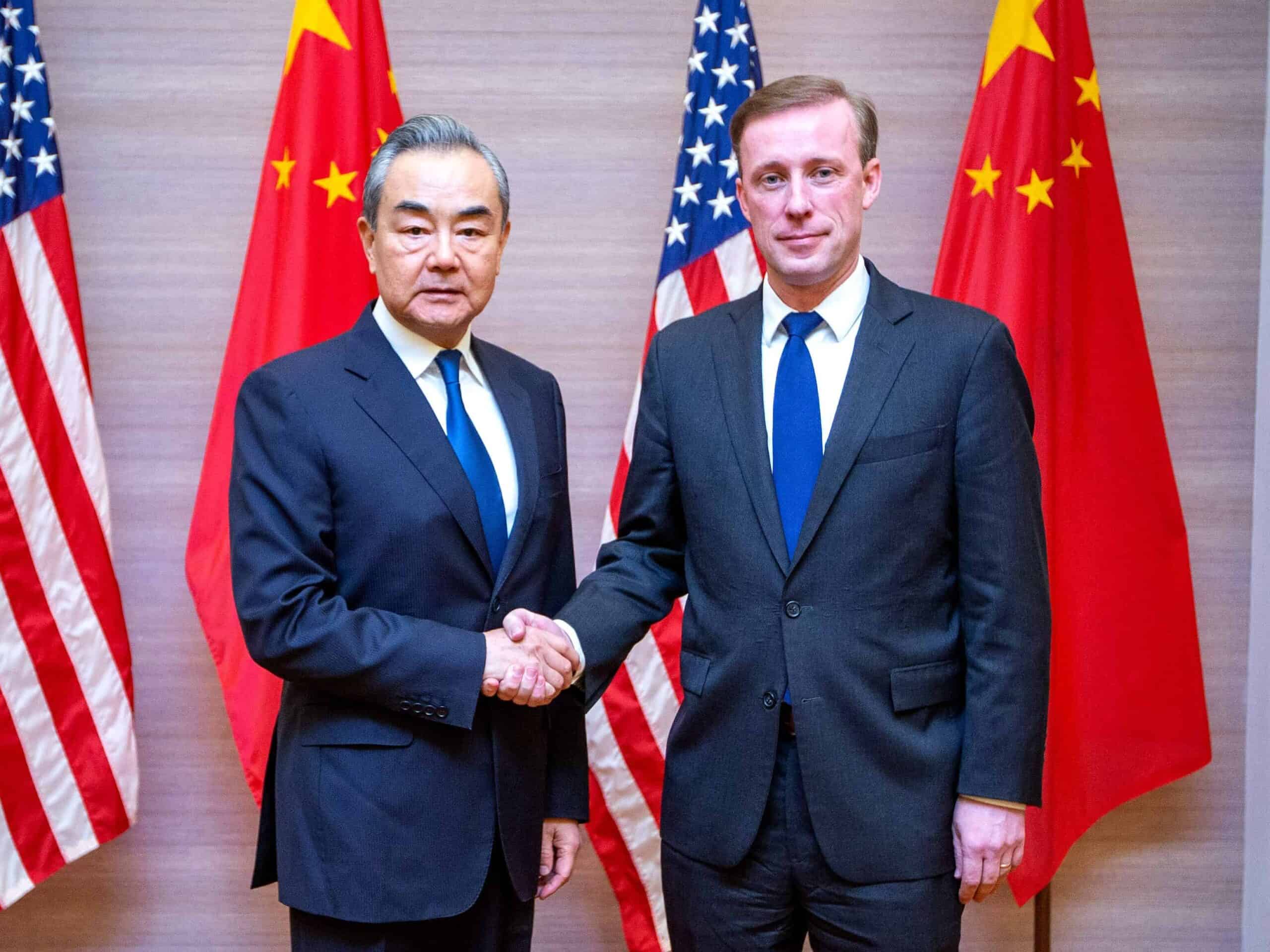

This drama has followed on from a position of relative calm in the bilateral relationship at the end of President Joe Biden administration. Biden’s team had pursued two parallel tracks that reinforced each other to strengthen U.S. influence in Asia and mitigate the risk of an armed confrontation between the United States and China: bolstering America’s diplomatic network in Europe and Asia and sustaining a set of high-level dialogues with China, the most crucial being that between Jake Sullivan, the former U.S. national security advisor, and his counterpart Wang Yi, China’s top foreign policy official.

The first track enabled the administration to approach China with greater leverage. The second track helped reassure U.S. allies and partners that the United States would make a determined effort to prevent strategic competition from veering into an armed conflict — a track that took on heightened urgency after then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s August 2022 visit to Taiwan, and the February 2023 sighting of a Chinese surveillance balloon over U.S. territory, threatened to derail bilateral ties.

…economic discord and diplomatic estrangement between the United States and China seem set to compound one another — precisely when the world’s two leading powers need to be buttressing military and strategic channels to reduce the risk of a war in Asia.

The Trump administration, too, is pursuing parallel tracks, but in ways that will likely combine to have the opposite effect: degrading America’s alliances and partnerships and impeding the resumption of productive diplomacy with China.

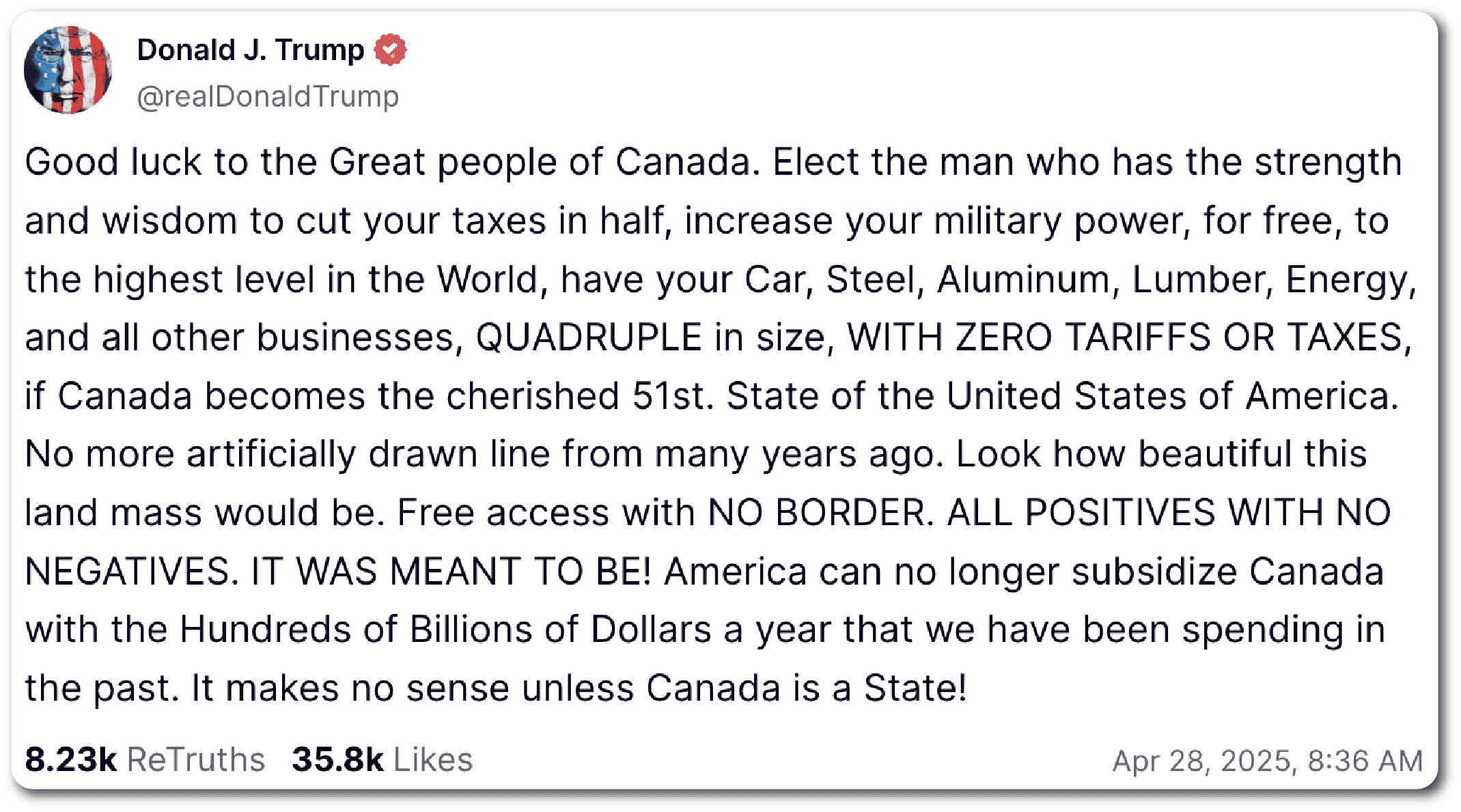

Pursuant to his desire to expand U.S. territory, Trump has insisted that Canada subsume itself into the United States as the latter’s 51st state and instructed his advisors to devise a plan for acquiring Greenland from Denmark. Between contending that the European Union “was formed in order to screw the United States” and suggesting that Ukraine is responsible for Russia’s invasion, Trump has further strained the transatlantic alliance.

Turning to Asia, he has, as during his first term, cast doubt on the strategic utility to the United States of its two most important alliances, with Japan and South Korea. In addition, he has gone far further this time around in suggesting that he views Taiwan in principally, if not exclusively, economic terms, musing that Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s decision to increase its investment in the United States by $100 billion would mitigate the impact of a Chinese invasion on the U.S. economy. His April 2 and April 9 tariff moves, meanwhile, suggest to U.S. allies and partners that American foreign policy is not appropriately flexible, but rather capriciously punitive. Despite renewed speculation that the United States might be able to loosen Russia’s embrace of China, the greater likelihood along current trendlines is that Washington will separate itself from core allies and partners through self-inflicted errors.

As for China, Trump runs the risk of overstating U.S. leverage. While he claims that it “wants to make a deal, badly, but they don’t know how to get it started,” Xi does not appear to feel much urgency to initiate negotiations. Nor would he be likely to recalibrate unless he were to assess that popular discontent with the state of the economy might jeopardize his grip on power — a fear that led him to end China’s “zero-COVID” restrictions in December 2022.

China is more structurally stressed today than it was when Trump first took office in 2017, but it is also more capable of withstanding tariffs and responding asymmetrically; it has raised the tariff rate on Chinese imports from the United States to over 147 percent, cancelled all orders of Boeing aircraft and purchases of U.S. liquefied natural gas, and halted its exports of several critical minerals and magnets, among other measures. In addition to further accelerating its efforts to de-risk financially and technologically from the United States, China will likely pursue opportunities to deepen its economic relationships across the developing world and stabilize its economic relationships with U.S. allies and partners.

During the Biden administration, dialogues below the leader level not only laid the foundation for meetings between Biden and Xi; as importantly, if not more, they also maintained a steady cadence of bilateral activity before and after those tête-à-têtes. If, as Politico reports, “Trump, not a deputy, is leading the administration’s strategy on China,” then a breakdown in communication between him and Xi could well prevent his advisors and their Chinese counterparts from building a supportive communications apparatus.

Unfortunately, neither of them will want to convey that he has yielded to the other; Trump claims that he has put America’s foremost strategic competitor on notice and wants to demonstrate a willingness to ratchet up U.S. economic pressure indefinitely, while Xi claims that he has showcased China’s resilience and wants to cast his country as a contributor to, not a disruptor of, global economic stability.

In a potential glimmer of hope, Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent noted last week that the current trade impasse between the two countries is untenable, with Trump saying the following day that U.S. tariffs on China would decline “substantially.” At least for now, though, economic discord and diplomatic estrangement between the United States and China seem set to compound one another — precisely when the world’s two leading powers need to be buttressing military and strategic channels to reduce the risk of a war in Asia.

Ali Wyne is the senior research and advocacy advisor for U.S.-China relations at the International Crisis Group.