When Chinese leader Xi Jinping hosted a rare meeting with private sector business leaders last month there was one glaring omission from the guest list: Robin Li, the 56-year-old founder and chief executive of Baidu.

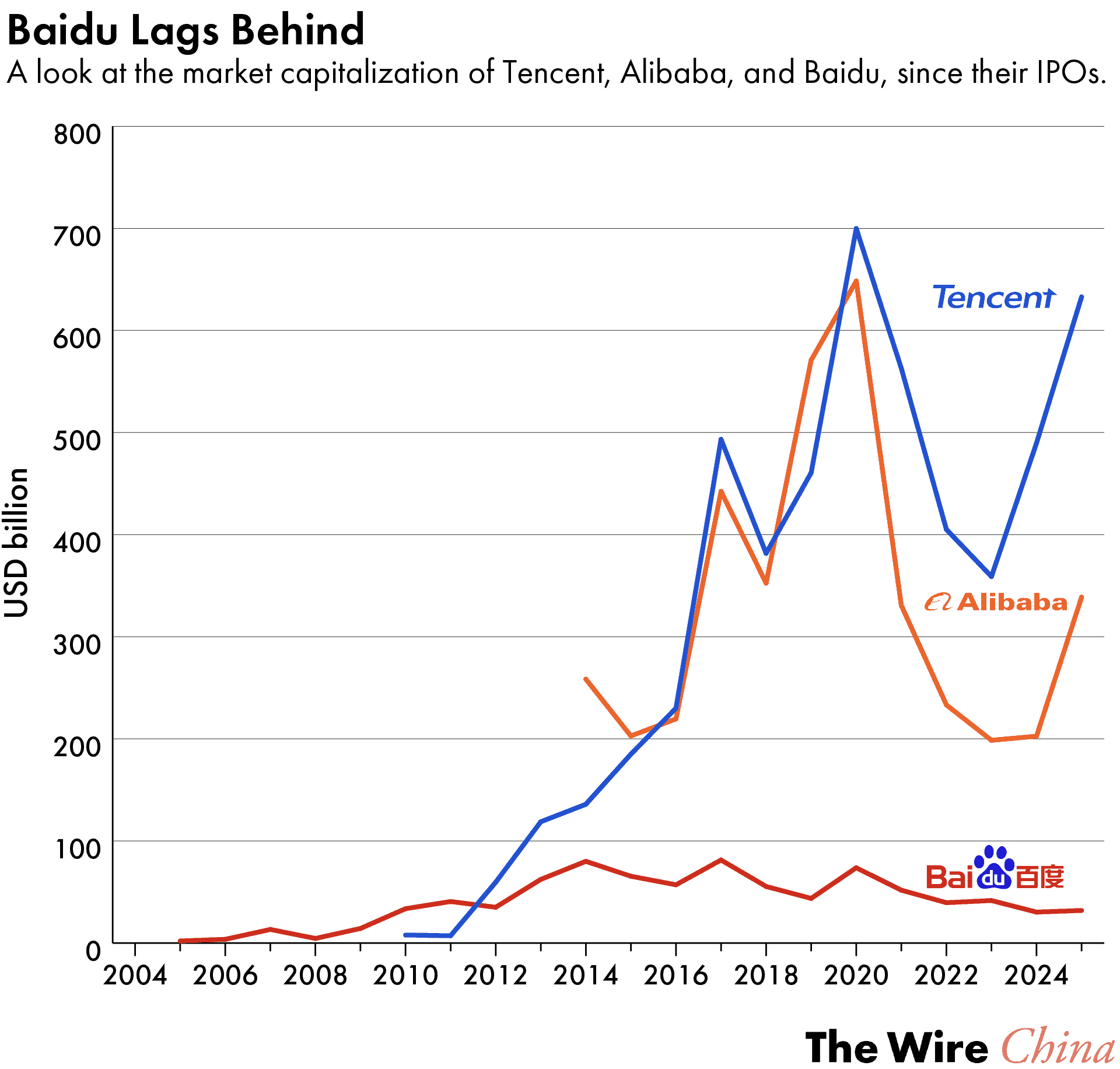

Once hailed as the “pride of China”, Li created Baidu as “China’s Google,” and the company was long recognized as a core member of China’s tech elite. In the 2010s, the so-called “BAT” triad — Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent — became shorthand for China’s incredible technological rise. When Baidu debuted on the NASDAQ on August 5, 2005, its stock skyrocketed 354 percent, instantly minting eight billionaires in China in the process.

But as Li’s absence last month helped underscore, those days are long gone. While Alibaba and Tencent’s market capitalizations have grown 60 and 240 percent respectively over the past decade, Baidu’s has been cut in half. To add insult to injury, even Jack Ma, Alibaba’s founder who just four years ago was in Beijing’s dog house, was invited to meet with Xi. When Li was left out of the meeting, the Hong Kong shares of Baidu plunged, wiping $2.4 billion off its market value.1Baidu also listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2021.

But Baidu, analysts note, has been struggling for a while now.

“Baidu missed a chance to move on from its old business model of search ads into new sectors,” says Kyle Chan, a Princeton sociologist who studies Chinese industrial policy. “Tencent now makes a large share of its revenue from gaming. Alibaba expanded into other areas, like payments. But Baidu continued to have the old model driving most of its core business.”

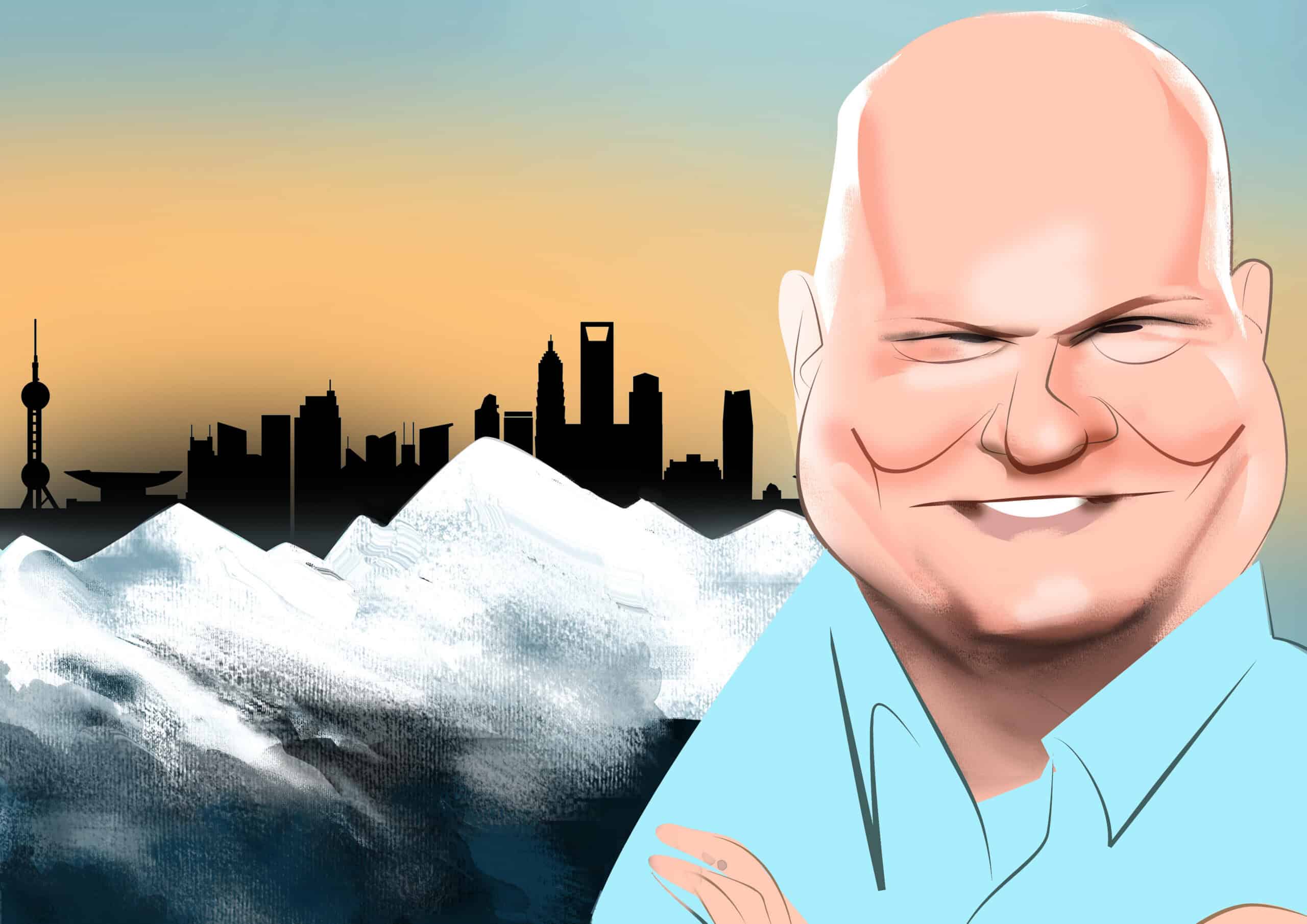

Duncan Clark, chairman of investment advisory firm BDA China, says the failure to adapt risks turning Baidu into “a faded movie star.”

Baidu has attempted numerous comebacks, of course. Over the past two decades, it has made multiple attempts at e-commerce, only to shut them down each time. It dabbled in online gaming, but sold its platform for a bargain price. And it had a short-lived experiment with a food delivery service.

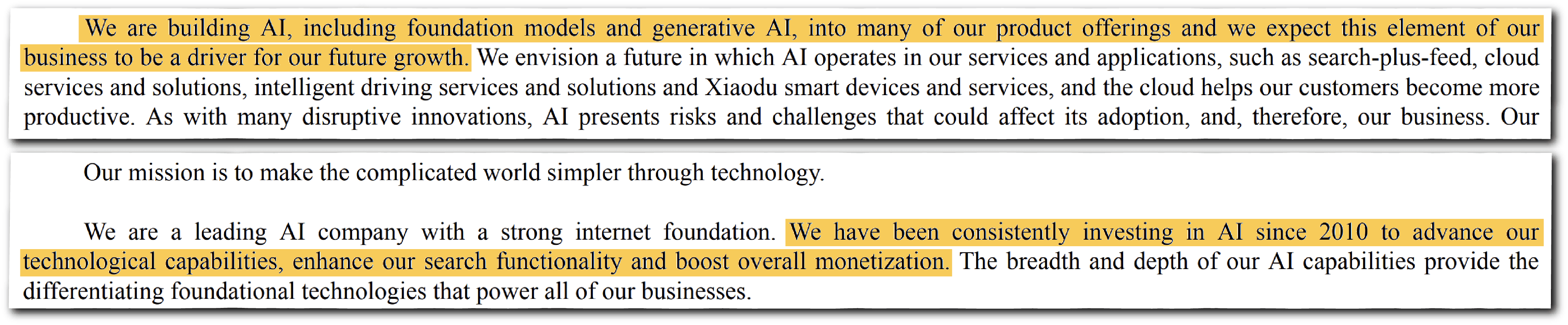

But Baidu’s biggest bet has been on artificial intelligence. For a company seen as “falling behind,” it was surprisingly ahead of the times in terms of AI investment and research. As early as 2013, it had established a deep learning research institute in Beijing to simulate the human brain. And by September 2016, Robin Li was publicly declaring Baidu’s transformation into an AI-driven company, saying “the next act of the internet is AI.”

Baidu announces its latest Ernie model, Ernie 4.5, March 16, 2025. Credit: Baidu via X

The company’s early pivot to AI, however, has led to uneven results. Its chatbot, Ernie Bot, garnered a lot of attention for being the first major Chinese-language model to debut after ChatGPT, but it was quickly overshadowed by ByteDance’s chatbot, Doubao. Adding to the company’s embarrassment, DeepSeek, a large language model that has recently surged in popularity, has forced a major shift in the company’s strategy: Baidu recently announced it would make its next-generation Ernie Bot open-source and free. And although Apple first chose Baidu to develop AI features for iPhone users in China, the U.S. giant has decided to work with Alibaba as well, The Information reported, “after the partnership with Baidu met with challenges.”

Yet Baidu’s investment in AI could still pay off, and 2025 is proving to be a pivotal year for the company’s long awaited comeback. In its most recent earnings report, Baidu said that while weak advertising demand led to lower revenue for the third straight quarter, Baidu’s net income doubled, largely driven by its AI business.

“While navigating near-term pressures, we are confident that our strategic AI investments will drive meaningful progress and foster long-term success,” Junjie He, Baidu’s interim chief financial officer, said in a statement on the company website. (Baidu did not respond to requests for comment.)

If they can continue to be successful with autonomous driving or push forward on AI, that will help the overall perception of the company to feel like a real technology leader again, rather than an old tech company from a previous generation.

Kyle Chan, a Princeton sociologist who studies Chinese industrial policy

The company is counting on its robotaxi business, called Apollo Go, to drive much of this progress. Last May, Chen Zhuo, general manager of Baidu’s autonomous driving unit, said the business “will be fully profitable in 2025.”

A video released by Baidu promoting Apollo Go, titled ‘When Robotaxis Become Part of Everyday Life’.

Today, Baidu leads the world in robotaxis and currently operates China’s largest fleet of self-driving vehicles: As of December, some eight million Apollo Go rides have taken place in more than 11 Chinese cities. For comparison, Waymo, the market leader in the U.S. that was developed by Google parent Alphabet, has completed five million rides in four cities.

“In the robotaxi sector, Baidu is undoubtedly a top player,” says Lei Xing, founder of AutoXing and co-host of China EVs & More. “Its city deployments and commercial fleet size clearly lead other competitors in China.”

With the market in China poised to grow — 77 percent of Chinese consumers favor autonomous driving, versus just 37 percent in the U.S. — Baidu is feeling bullish. In 2021, the company poured around $3.5 billion into research and development — an investment that nearly matches its total net profit in 2020. The company has said it plans to double the number of cars in its fleet, and it is targeting overseas expansion in Hong Kong, Singapore and the Middle East.

In the recent earnings call, Robin Li also announced that 100 percent of its Apollo Go fleet is now fully unmanned, meaning the company no longer has to employ safety drivers behind the wheel, a significant cost savings.

“If they can continue to be successful with autonomous driving or push forward on AI, that will help the overall perception of the company to feel like a real technology leader again, rather than an old tech company from a previous generation,” says Chan.

Yet, while the early lead is promising, some analysts say Baidu’s robotaxi business still faces a number of challenges, and its foray into AI is a classic example of “起个大早,赶个晚集,” a Chinese saying that means “getting up early and catching up late.”

“Even though it often has the right strategy and is first to recognize the potential of many new technologies,” says Rui Ma, founder of TechBuzz China, “it has not [yet] been able to turn those into lasting advantages.”

‘AI IS THE MAIN COURSE’

The seeds for Baidu were planted in the 1980s, when Robin Li (Li Yanhong), then a high school student from Yangquan, a poor city in Shanxi province, was sent to Taiyuan, the provincial capital, to compete in a national youth programming contest.

Li lost the competition, but while he was in Taiyuan, he visited a bookstore and was astonished to find shelves filled with programming books. His high school only had one programming textbook, and in that moment, Li recalled in a documentary, he realized there was “a huge imbalance in information and resources.”

“People are so unequal in terms of information and resources,” he recalled in an interview. “I wanted to make it easy and equal for everyone to access information.”

Li went on to enroll at Peking University, one of China’s top institutions, where he majored in Library and Information Science. After graduating in 1991, Li applied to, and was rejected from, the top computer science graduate programs in the United States, but the State University of New York at Buffalo ultimately offered him a scholarship.

As a summer intern at Princeton’s Panasonic Information Technology Institute in 1993, Li realized his true interests lay outside academia.

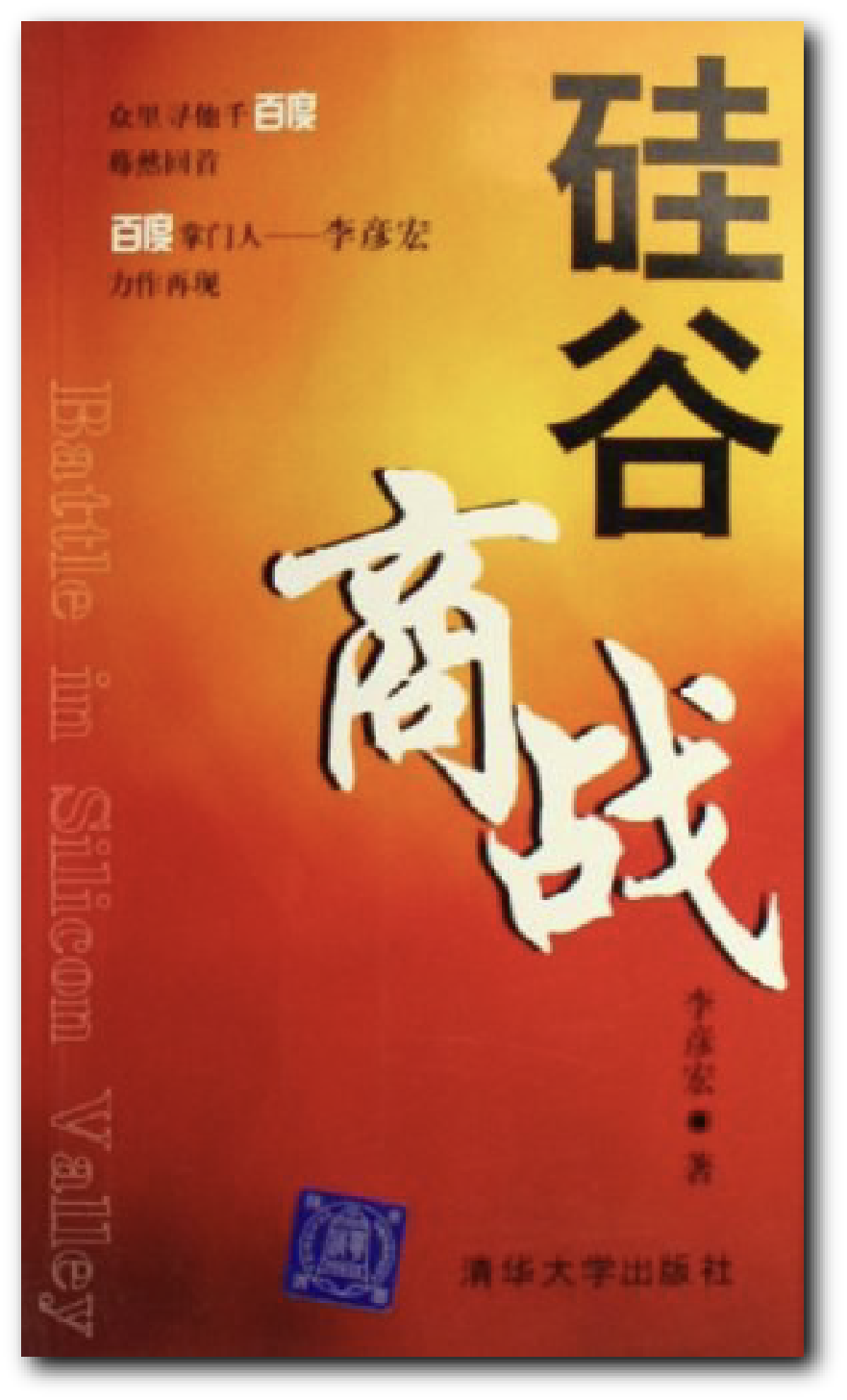

“What really makes me feel good is not how many papers I publish in the best academic journals, but how many people need and use what I do,” he later wrote in his 1999 book, Silicon Valley Business War.

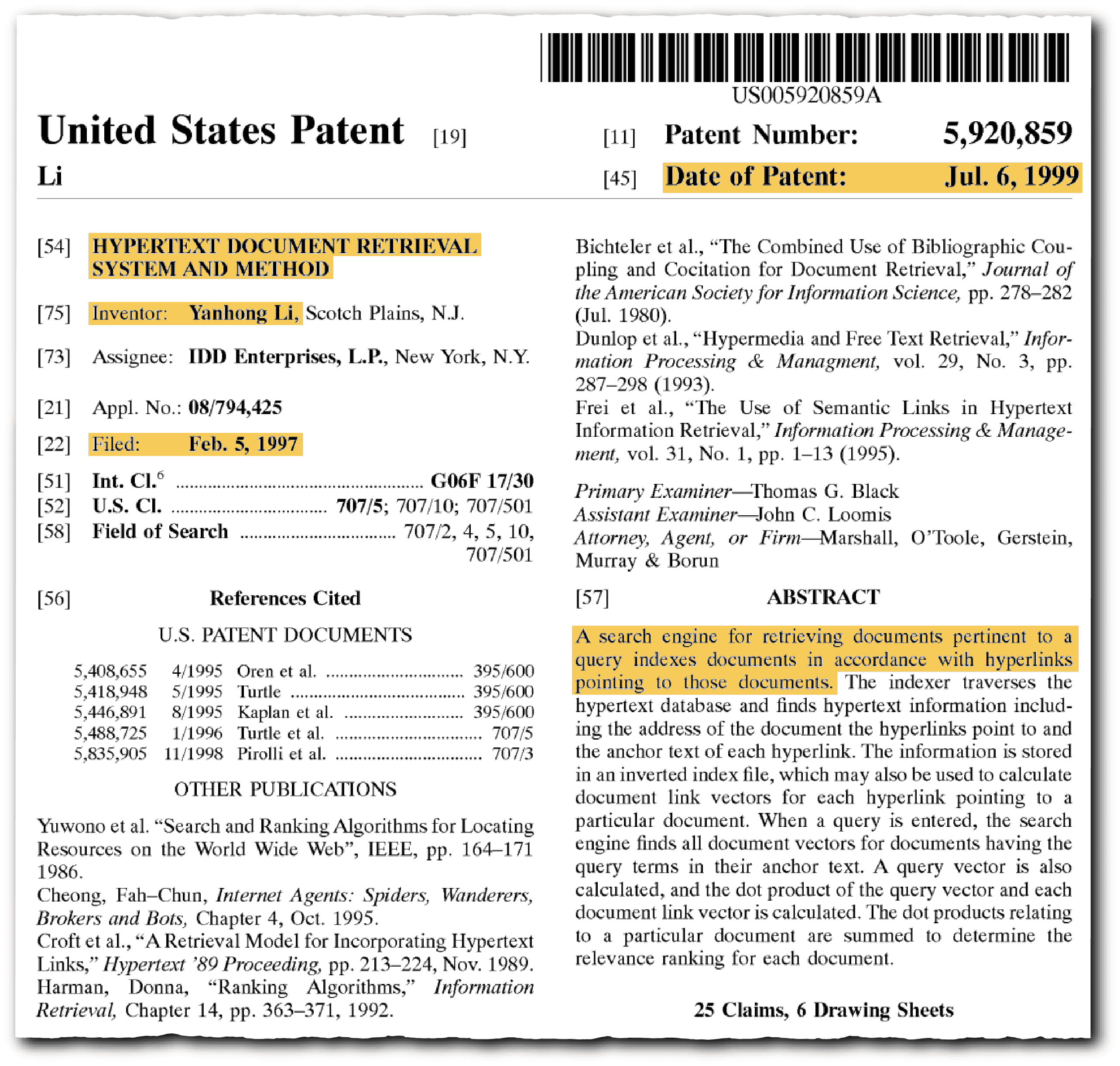

After earning his master’s degree in 1994, Li abandoned plans for a PhD. He joined the New Jersey division of Dow Jones & Company and helped develop software for the online edition of The Wall Street Journal. At the same time, he devoted hours to developing his own search engine technology, which he called “hyperlink analysis,” and even filed a patent for it in 1997, almost a full year before Google filed a patent for its PageRank Algorithm.

“I went into the search engine area earlier than Google,” Li has said. “I invented the hyperlink analysis, one of the basic inventions that decided development trends and direction of modern searching engines, earlier than Google. Technically, I do not feel we need to imitate others.”

Li’s patent was approved in 1999, at which point he decided to strike out on his own. The timing was fortuitous: He had recently moved to Silicon Valley to join Infoseek, a leading internet search company at the time, but after Disney bought a stake in Infoseek, the company’s focus was shifting from search to content.

Li reached out to Eric Xu (Xu Yong), a well-connected friend in Silicon Valley, for guidance. Xu, a biochemist, had experience with biotech companies in the U.S. and had just made a documentary about entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley. When Li revealed he wanted to go back to China to start an internet company, Xu helped Li raise $1.2 million from two Silicon Valley Venture Capital firms — Integrity Partners and Peninsula Capital — and went on to serve as Baidu’s first executive vice president.

On Christmas Day 1999, Li returned to Beijing to start Baidu, which translates to “a hundred times.” The name was inspired by a Song dynasty poem: “I have searched for her a hundred times, or even a thousand times, in the crowd, and turned around, and inadvertently found her in the sporadic lights.”

For Baidu, the equivalent of Google’s garage origin story was a hotel room near Peking University. From there, Li recruited a professor and five students to develop his search engine, and within five years, Baidu was profitable.

Although Baidu was, in many ways, following Google’s playbook, the U.S. giant didn’t make much of a dent in Baidu’s market share when it entered China in 2005. Because Google did not take the Chinese market seriously enough, says Yu Zhou, a professor at Vassar College who wrote a book on the origins of China’s tech industry, Baidu was more responsive to young Chinese internet users and capable of capturing trending topics within China.

I think the story with Baidu is always the same: the execution, which is a reflection of the leadership and culture. It’s been very bad at keeping top talent.

Rui Ma, founder of TechBuzz China

“China was a very fast-moving market,” she says, “but foreign companies just had some low-level employees there. Google had Kai-Fu Lee, but he was doing research. In the business operation, Google didn’t have very high-level decision makers.”

In August 2005, Baidu successfully listed on the NASDAQ, instantly valuing the company at $4 billion. At its peak, Baidu even surpassed Tencent, briefly becoming China’s most valuable internet company. And after Google withdrew from China in 2010 due to issues with censorship and cyber-attacks, Baidu’s market share rose to a record high of 70 percent.

But a critical oversight was looming: In 2009, China launched its 3G network, and Apple introduced its iPhone to the country, heralding the onset of the mobile internet era. Li underestimated the significance of this shift, analysts say, failing to see how users would come to prefer apps over traditional web browsing. By 2011, Tencent had launched WeChat, followed by Alibaba’s partnership with social media company Weibo in 2013 to attract online shoppers. These platforms siphoned search traffic from Baidu at a time when paid search advertising made up 99.5 percent of the company’s total revenue.

“In 2013 and 2014,” Li said in a documentary produced by Baidu, “I thought every day: am I really finished? Is the mobile internet era going to eliminate me?”

Baidu started to make strategic moves in 2013, acquiring e-commerce platforms in order to boost its online marketing revenue, but Li also wanted to reclaim Baidu as a technology company, not an ad sales company. As a search engine, the company’s focus had been on natural language processing and the idiosyncrasies of the Chinese language — a natural fit for deep learning research and a cornerstone of AI. Li doubled down.

“We aim to attract the world’s foremost experts in deep learning, building a robust foundation for our product and business development in the coming year,” Li declared at an internal meeting in 2012. “Believe in the power of technology; the future is in our hands.”

In 2013, Baidu established the Deep Learning Institute, with Li himself taking the helm as director. Over the next five years, Baidu significantly expanded its research operations, adding a total of five institutes, including two in Silicon Valley, and hiring top talents such as Andrew Ng, co-founder of Google Brain, Lian Wu, former Chief Software Architect at AM, and Qi Lu, a former Microsoft executive.

By 2017, Baidu put forward the slogan “All in AI.”

“AI is a change comparable to the industrial revolution,” Li said at the company’s annual industry conference that year. “The internet is just the appetizer, AI is the main course.”

A demonstration of Baidu Maps in Guangzhou. Credit: MaxAndTrends

MAPPING THE FUTURE

Today, Baidu’s AI business consists of several revenue streams, including large language models and cloud computing. But its autonomous driving business, Apollo Go, is the only one that is a leader in its field. Analysts say the company’s technology is not quite as impressive as Tesla’s, which relies mostly on AI vision, but Baidu has still thrived for one simple reason: its dominance in high-precision maps in China, which (like Google Maps) Baidu initially developed in 2005 to augment its search engine capabilities.

“Baidu has map data, which is a big advantage in China,” says David Yufei Chang, who spent three years working in Baidu’s search and autonomous driving divisions and now runs his own autonomous driving company. Baidu’s competitors, like WeRide and Pony.ai, “are restricted by surveying and mapping qualifications. There are only five or six institutions in China that can really provide navigation-level maps.”

This advantage allowed Baidu to quickly prove itself in autonomous driving. Back in 2017, Li drove a Baidu autonomous vehicle through Beijing’s streets to a tech conference, live-streaming the self-driving experience for attendees. The PR stunt was a massive success even though it ended in a snag: Li received a traffic ticket, as self-driving cars were not yet authorized on public roads.

Baidu’s historic position as a tech leader in China helped it clear these early hurdles with the government: Today, Baidu has obtained robotaxi operation licenses in 11 cities in China, significantly more than its competitors.

“There are three key points to the robotaxi business: technical strength, in which Baidu is not the best but not bad either; cost control, in which Baidu has kept the price of the RT6 [its latest model robotaxi] below 200,000 yuan; and government relations, because robotaxis involve people’s livelihood and safety,” notes Chang. “Government support is crucial, and unlike smaller companies, Baidu can get policy support.”

On the cost issue, Baidu has benefited from China’s robust industrial supply chain, which can provide cheaper lithium batteries, Lidar systems, sensors, and other components. Indeed, western competitors are shocked by the low cost of Baidu’s cars, which are built by JMEV (Renault’s joint venture with Jiangling Motors Corporation Group) for around $27,500. For comparison, the equipment cost for Waymo’s fifth-generation robotaxi, the electric Jaguar I-Pace vehicles, could reach up to $100,000, Waymo’s CEO stated in a podcast last February.

Still, Xing, of AutoXing, notes that Baidu’s “lead is not as big as you might think.”

As AI develops, autonomous vehicles are gathering and using real-time environmental data more, reducing the reliance on high-precision maps. In May last year, XPeng Motors, a Chinese EV manufacturer, announced that its urban intelligent driving system no longer requires online maps. And although Tesla collaborates with Baidu and uses its maps, Tesla has explicitly stated that it “doesn’t rely on high definition maps.”

“In the field of autonomous driving, the reliance on maps is becoming increasingly slight,” says Liu Shaoshan, founder of a full-stack visual intelligence company who previously served as a senior architect in Baidu’s autonomous driving division.

Li often has very good judgment on the way the industry’s moving, but he cannot sit on his hands and let people get on with it. Partly as a result, Baidu never has really realized its full potential.

Duncan Clark, chairman of investment advisory firm BDA China

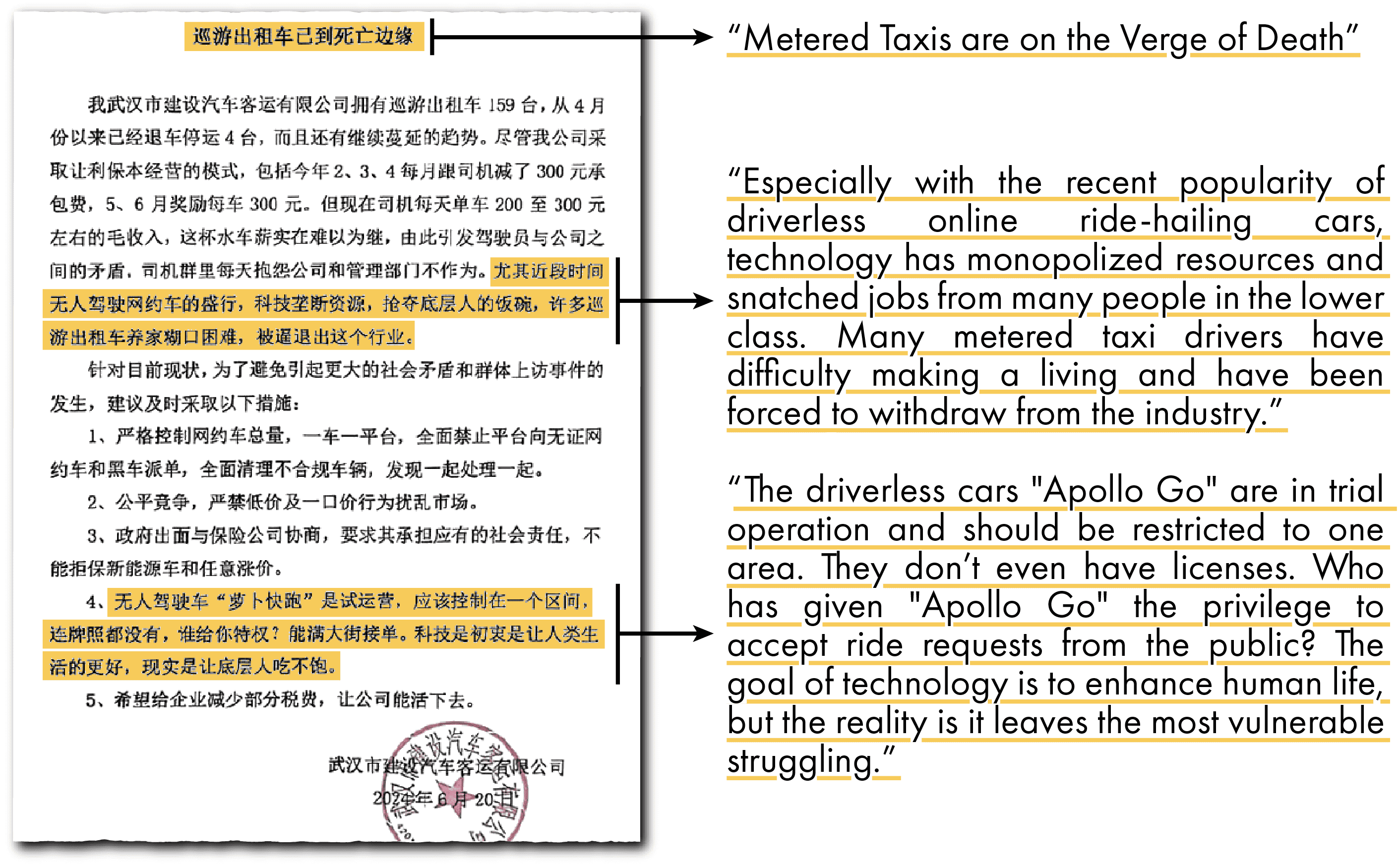

Another challenge for Baidu is whether it can maintain consistent and stable demand for its robotaxis. Baidu has been heavily subsidizing the cost of its rides, contributing to its popularity and destabilizing the regular taxi industry: According to Chinese state media reports, last July, the cost of a 10-kilometer ride with Baidu’s robotaxi in Wuhan ranged from 4 to 16 yuan ($0.60 to $2.30), whereas the cost for a conventional ride-hailing service ranged from 18 to 30 yuan ($2.52 to $4.20).

“When the subsidies disappear and the prices of robotaxis are much higher than traditional taxis, the question is whether people will still be willing to use robotaxis,” says Ricco Kampfer, team lead in autonomous driving at the consultancy P3.

In the end, however, despite Baidu’s significant head start in AI and autonomous driving, many analysts warn that Baidu’s most enduring challenges remain similar to what they have always been: internal management issues and a loss of top talent. Currently, for instance, Baidu’s principal competitors in China’s robotaxi market are Pony.ai and WeRide, both of which were founded by former leaders of Baidu’s own robotaxi division.

“I think the story with Baidu is always the same: the execution, which is a reflection of the leadership and culture,” says Ma, at Tech Buzz China. “It’s been very bad at keeping top talent.”

Clark, at BDA, notes that Li has always been a good engineer but never a great manager. “Li often has very good judgment on the way the industry’s moving,” he says, “but he cannot sit on his hands and let people get on with it. Partly as a result, Baidu never has really realized its full potential.”

The question going forward is if it ever will.

Yi Liu is a New York-based former staff writer for The Wire. She previously worked at The New York Times and Beijing News. Her work has also appeared in China Project, ChinaFile and Initium Media.