After a two-year lull, the number of Chinese companies looking to list on domestic stock markets is back on the rise.

Last Tuesday Healthgen Biotechnology, which makes blood plasma proteins from genetically modified rice, launched an initial public offering process through which it hopes to raise 2.4 billion yuan ($336 million) on the STAR market, Shanghai’s version of the Nasdaq. Xi’an Eswin Material Technology, which makes silicon wafers for chips, and BeBetter Med, a Guangzhou-based biotech company that develops cancer drugs, have also started to seek backing for their upcoming IPOs.

The three companies share one thing in common: None has yet made a profit.

They are among the first batch of Chinese firms looking to go public under new rules that make it easier for innovative startups to raise funds, even if they are yet to break even. In the past, Chinese regulators have often been cautious about which companies they approve for a public listing, hoping to avoid investors plowing money into dud stocks.

Their easing grip is a positive sign for industries that align with Beijing’s priorities. But lowering the bar for IPOs could bring other risks.

“Their [Healthgen and others’] listing is going to convince people that this is a surefire winner because the government’s behind it,” says Andrew Collier, managing director and founder of Orient Capital Research. “In the near term, it could provide some additional juice to the market. But when these companies fail to deliver the results that people expect, that juice will evaporate.”

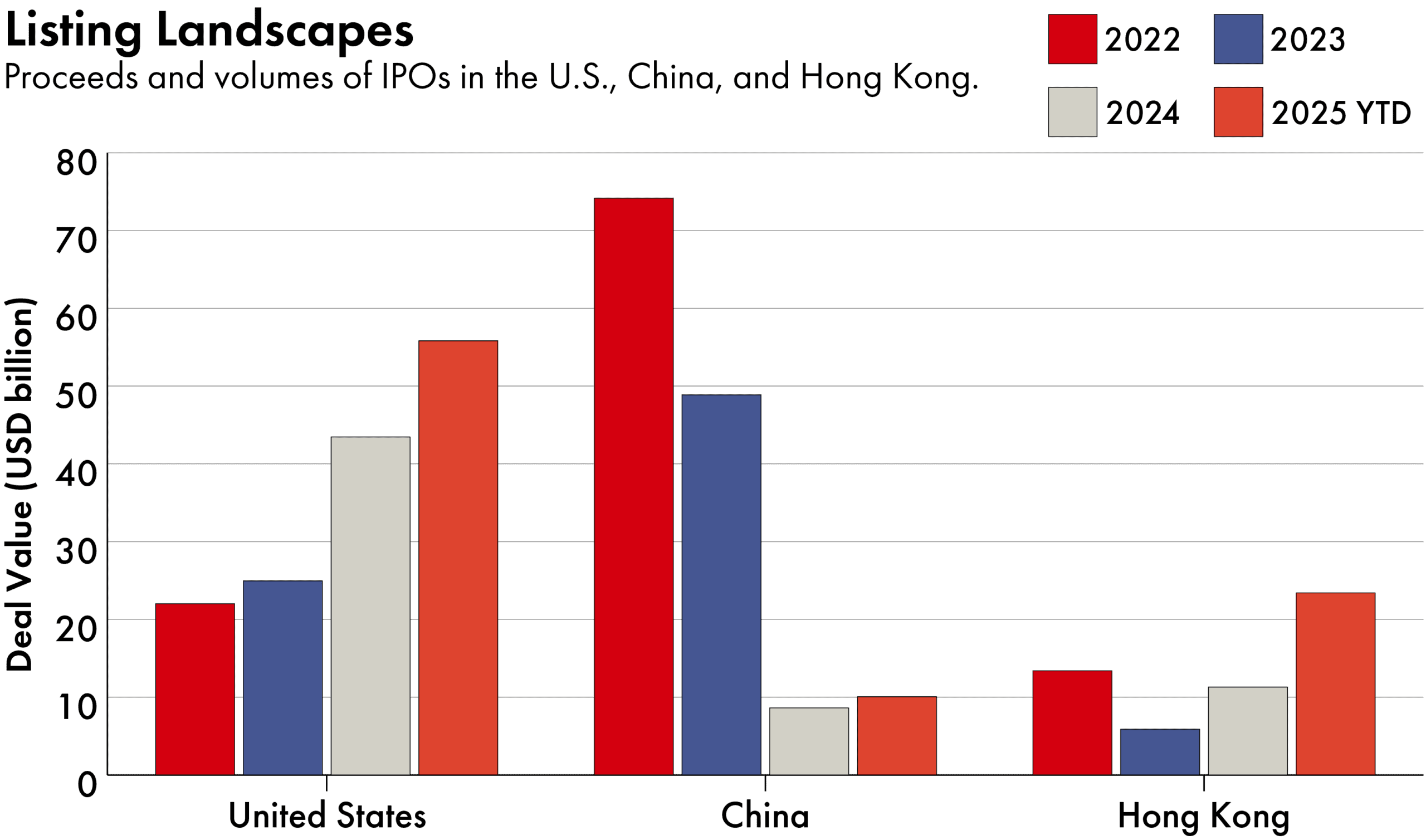

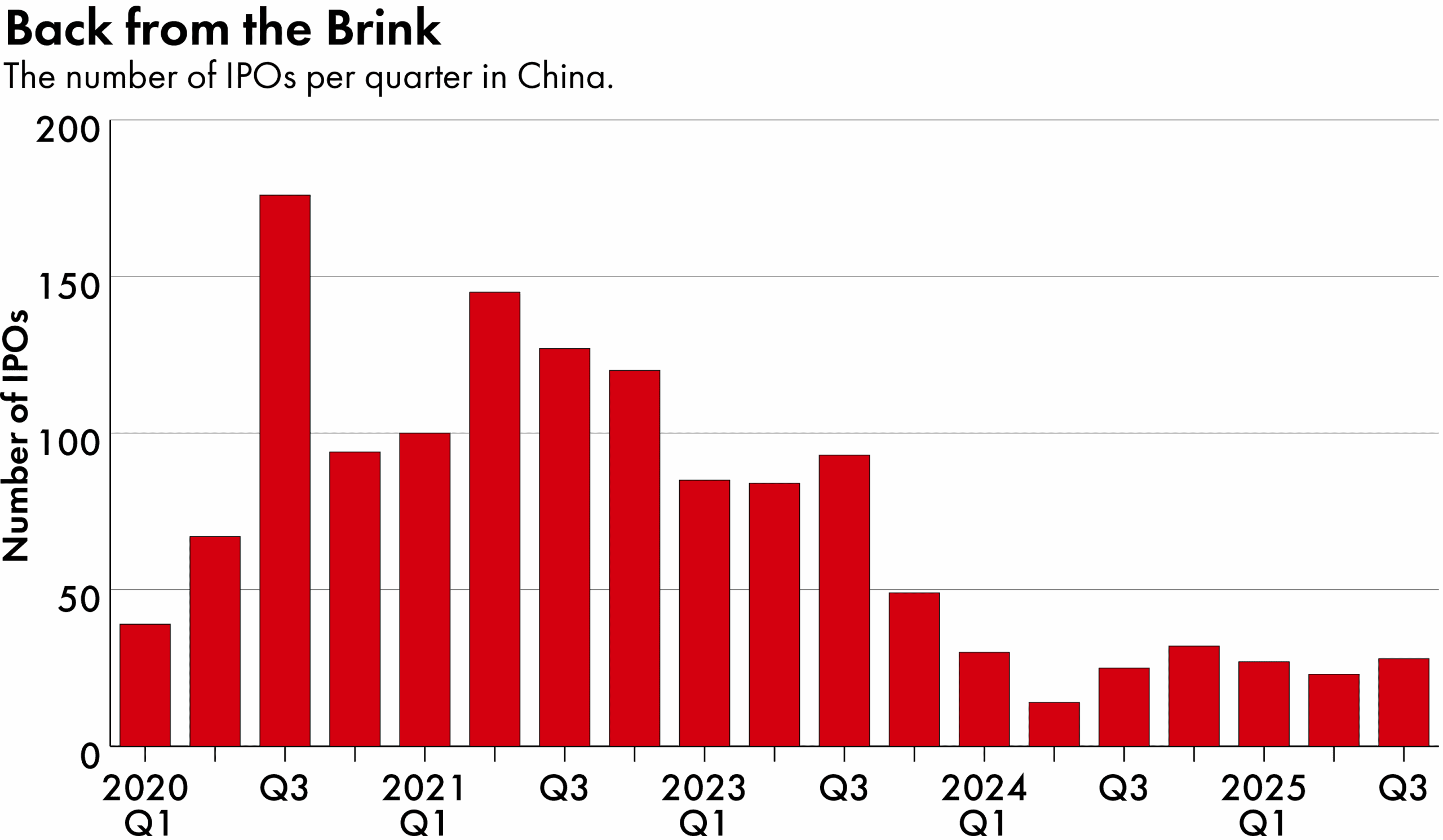

The numbers this year so far seem encouraging. 78 companies listed in domestic Chinese stock exchanges in the first three quarters of the year, according to Deloitte, raising a total of 77 billion yuan ($10 billion), a 61 percent increase year-on-year.

Companies in so-called ‘hard tech’ industries, such as semiconductors, clean energy, and biotech, are driving the recovery. In July, Huadian New Energy, a state-owned power producer, raised 15.8 billion yuan ($2 billion) in the biggest mainland IPO of the year so far. Unitree, a star robotics firm from Hangzhou that is gearing up for a listing in Shanghai next year, may produce another blockbuster.

They want to push China towards a capital raising model that’s less dependent on bank debt, but at the same time, are very cautious about the impact of stock market volatility on retail investors and the overall macro economy.

Nicholas Borst, director of China research at the Seafarer Capital Partners

The level of activity is still far from the peak in 2021. But it is an improvement from the historical lows last year, after Chinese authorities tightened the screws on IPOs to stabilize falling stock prices.

To help revive the market, China appointed Wu Qing — known as “Broker Butcher” for his tough tactics in previous regulatory roles — to lead the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) last February. Chinese authorities last month seized Wu’s predecessor, Yi Huiman, amid an investigation into alleged corruption.

Chinese authorities are walking a tightrope, says Nicholas Borst, director of China research at the Seafarer Capital Partners.

“They want to push China towards a capital raising model that’s less dependent on bank debt, but at the same time, are very cautious about the impact of stock market volatility on retail investors and the overall macro economy,” he says.

The latest moves reflect this calibration. In April, China’s top policymaking body the State Council issued new guidelines demanding financial markets oversight with “teeth and thorns”.

The CSRC has in turn continued to pepper IPO applicants with so many questions that many were deterred from pursuing a listing. Over 400 firms withdrew their applications last year, per data from Wind, a financial terminal.

The trend has continued this year. Chint Anneng, a Wenzhou-based unicorn that sells solar panels to households, backed out of an IPO last month, while dairy company Sichuan Jule Food last week gave up on its fifth attempt to get listing approval.

But regulators have also reopened the door to firms that are part of China’s “new quality productive forces”, Xi Jinping’s current economic policy priority. After a two-year lapse, the Shanghai stock exchange in July revived the “fifth listing standard” that allows an unprofitable company to list if it demonstrates promising growth potential and has an estimated market value of at least 4 billion yuan ($560 million). Authorities also extended this standard from biotech to other emerging sectors, such as low-altitude economy, commercial aerospace and AI.

“If a company has innovations that can help the country overcome tech chokepoints, it will likely get a greenlight,” says Edward Au, Southern Region managing partner at Deloitte China.

One prominent example is Moore Threads, a chipmaker from Beijing. Authorities approved its IPO application at record speed last month, even though the company has racked up 5.2 billion yuan ($730 million) in losses since 2022. The firm aims to raise 8 billion yuan ($1.12 billion), partly to fund the development of AI chips and graphic processing units.

“If you start listing companies where your average investor really doesn’t understand what they’re getting into, it’s much more risky,” says Collier. “If these companies fail to deliver the results people expect, then all of a sudden, Beijing is going to have egg on its face.”

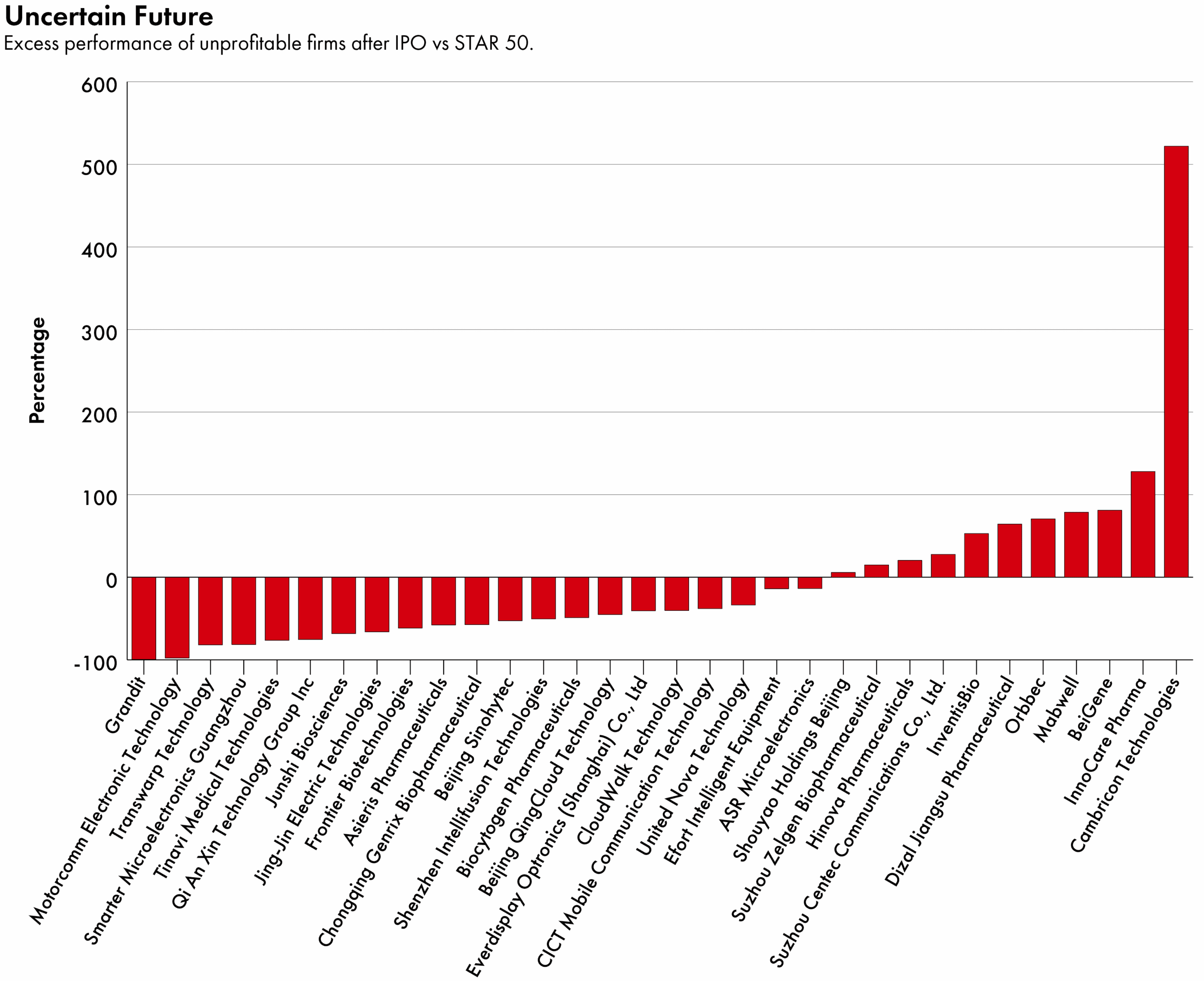

“There are good reasons to be cautious,” says Liang Ding, an independent economist based in Shanghai. Of the 54 unprofitable companies that had debuted on the STAR market before the fifth listing standard was suspended in 2023, 32 are still unprofitable. Most underperformed compared to the top segment of the STAR market, Liang’s analysis found.

Still, there are also outliers, such as Cambricon, a Beijing-headquartered AI chipmaker whose stocks surged 20-fold since its debut in 2020. The company reported its first quarterly profit at the end of last year, and its revenue has skyrocketed in the first half of this year, amid China’s self-sufficiency drive. Riding the tech rally, it became the country’s most expensive stock in August, despite a recent pullback.

The bigger question though, is whether the current enthusiasm of the stock market is sustainable. If there is no fundamental improvement of the Chinese economy and corporate profitability, could the strong market continue into next year?

Vincent Chan, China strategist at the investment advisory Aletheia Capital

Some fear that the relaxed profitability standard for some IPO hopefuls will worsen a structural imbalance in China’s economy, whereby high tech sectors thrive with state support while the rest of the economy languishes.

“After all, besides technology enterprises that bear the responsibility of strategic competition with the United States, a large number of enterprises related to the employment and daily lives of Chinese people also need capital,” says Shen Meng, a director at Beijing-based investment bank Chanson & Co.

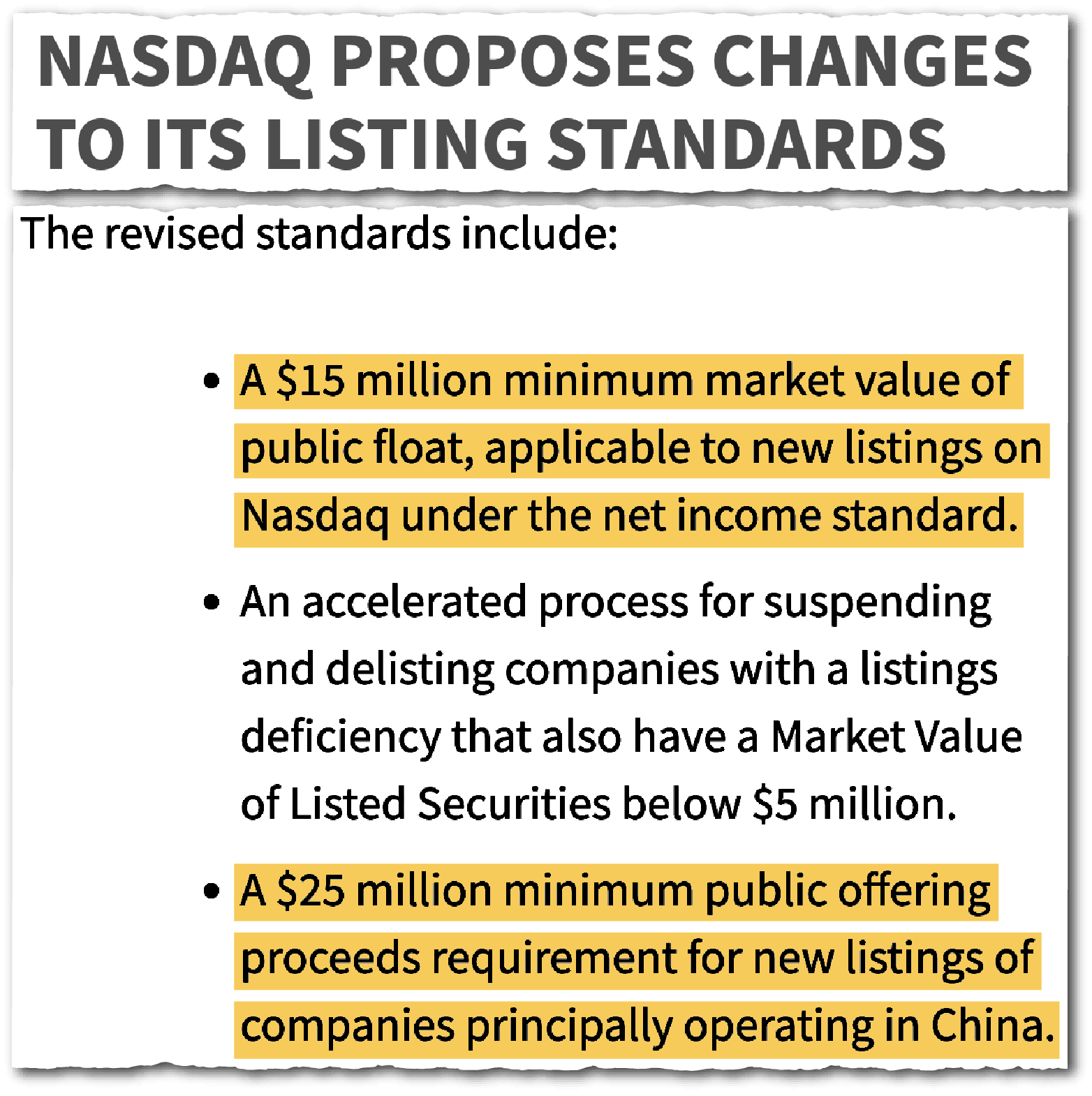

Companies that don’t align with Beijing’s priorities may find themselves with few other options. With the Sino-U.S. trade war escalating, Chinese firms face getting booted off American stock exchanges. Last month, Nasdaq proposed stricter standards, including a minimum market cap of $15 million, that could cut the number of Chinese companies on the market by half.

Some have turned to Hong Kong, fueling an IPO boom. The city’s stock exchange topped global ranks as 66 companies raised a total of HK$182 billion ($23.6 billion) in the first three quarters. Most of them were Chinese firms. Nevertheless, the Hong Kong market is “not friendly” to small and medium-sized mainland enterprises, Shen says.

Whether Chinese bourses can see a more substantial rebound hinges on market conditions. Chinese equities have made steady gains in the last year, buoyed by government stimulus and optimism about the country’s tech advances. The CSI300 Index is up 30 percent in the last twelve months, double that of S&P 500. But some fear the rally may run out of steam.

“The bigger question though, is whether the current enthusiasm of the stock market is sustainable,” says Vincent Chan, China strategist at the investment advisory Aletheia Capital, who found disappointing profit and sales growth among the 4,000 Hong Kong and Chinese stocks he tracks. “If there is no fundamental improvement of the Chinese economy and corporate profitability, could the strong market continue into next year?”

Rachel Cheung is a staff writer for The Wire China based in Hong Kong. She previously worked at VICE World News and South China Morning Post, where she won a SOPA Award for Excellence in Arts and Culture Reporting. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Columbia Journalism Review and The Atlantic, among other outlets.