For alert foreigners who visit or live in China, this summer has been particularly stressful. A Beijing court sentenced a Japanese Astellas Pharma executive to prison for espionage. Wells Fargo & Co. suspended staff travel after one of its Chinese-American managing directors visited and discovered she couldn’t leave. News broke that state security had detained and interrogated a visiting U.S. Commerce Department employee during a personal trip and subjected him to an exit ban. And BlackRock Inc. warned employees not to use any corporate phones or computers in China.

Sadly, these are only the most recent examples in a growing inventory of incidents in which foreigners fall victim to China’s draconian security apparatus and increasingly weaponized political-legal system.

I know because I lived it. After the Beijing State Security Bureau wrongfully detained me as a political hostage in 2018, I experienced for over a thousand days how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) ruthlessly uses foreign citizens as bargaining chips in diplomatic disputes. We’d all like to believe the “Meng-Two Michaels Affair” was an isolated crisis, but that would be dangerously naïve. Since my release in 2021, I’ve fielded dozens of queries about travel to China and tracked incidents and policy developments. While my own geopolitical circumstances were unique, there are mounting signs that foreign nationals in the People’s Republic are playing a kind of Chinese roulette with their personal security.

Travel to China now requires assessing two risks: first, that a state security apparatus which is incentivized to over crank might deem your past or current activities suspicious, and second, that while you’re there, your government or organization might do something to offend the CCP — including, but not limited to, the legitimate detention of a Chinese executive, scholar or intelligence officer. Your profile under the first risk may influence your odds of being targeted under the second. It’s not only your own intentions or actions, but also how Party-state elements perceive you and your affiliations — or arbitrarily decide to portray you for personal, bureaucratic, or political purposes.

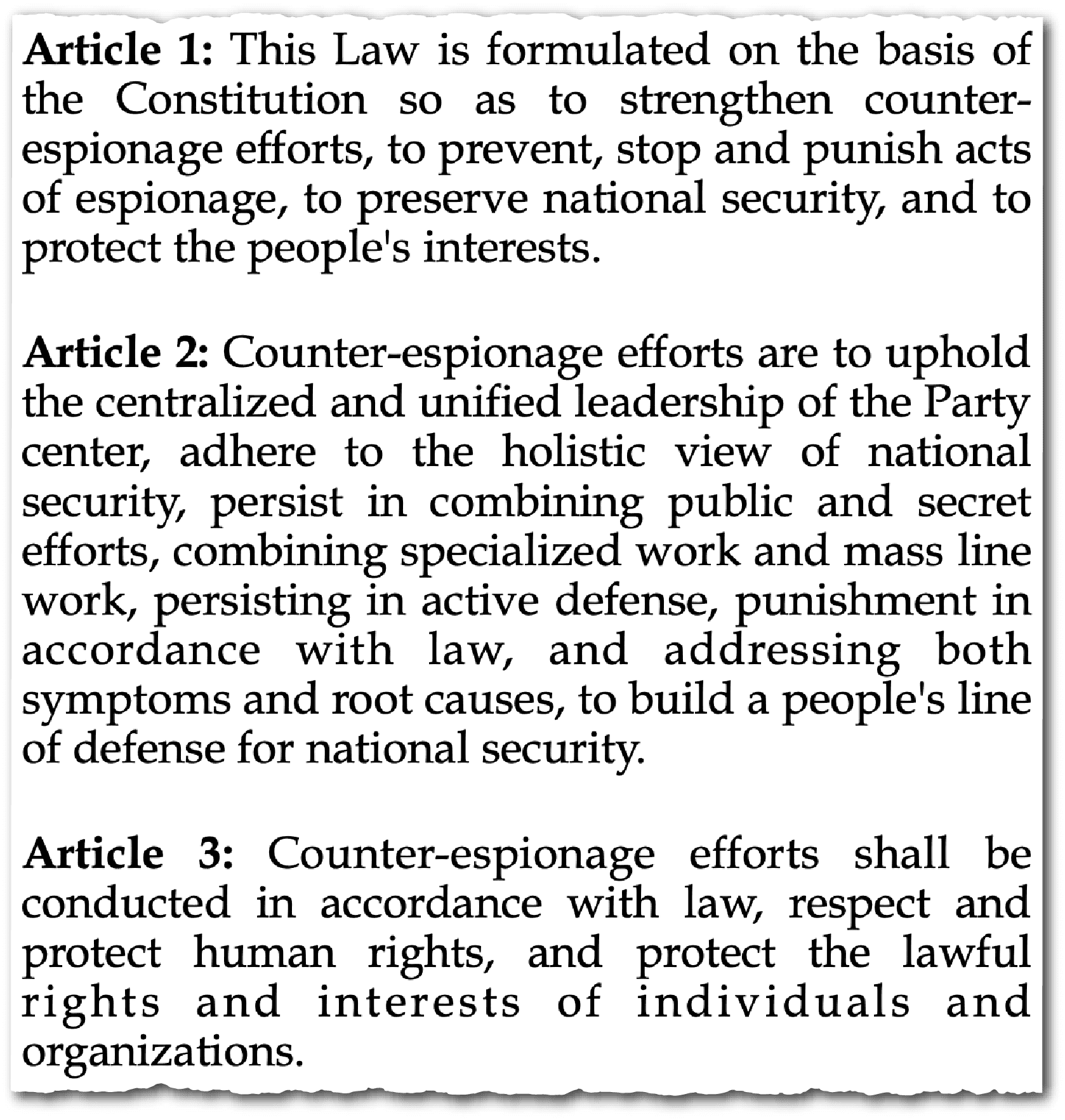

Under the aegis of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s Comprehensive National Security concept, several new and revised state security laws have brewed a perfect storm of risk that turns routine business activities and academic exchanges into potential violations. China’s laws and white papers are lagging indicators: these ones merely formalize and incentivize hardening practices of monitoring and detaining foreigners and accessing and controlling their data.

The 2023 Counter-Espionage Law casts such a wide net that taking photos, looking up information online, posting to social media outside China, or having conversations with PRC nationals could be deemed espionage.

…money, technology and insights are still welcome, but foreigners must tread carefully in an increasingly controlled and securitized landscape in which bad luck can bring personal tragedy.

The 2024 update to the State Secrets Law expansively includes “documents, data, materials, and items related to national security and interests.” The effect is to criminalize normal business intelligence, research and reporting — retroactively if need be.

Most recently, in May 2025 the State Council released an unprecedented white paper on “China’s National Security in the New Era” that reinforces the primacy of security — particularly regime security — and the imperative to defend against foreign hostile forces. It asserts an authoritarian framework in which political security trumps individual rights and Western legal norms — such as due process — are subversive.

In open societies, information is public unless formally designated otherwise. The Party-state’s default is the reverse: government-related information is classified unless official mouthpieces disclose it. The scope of politically sensitive topics now includes previously safe areas such as economic indicators and business conditions. Even interactions once considered benign — like asking questions at a conference or conducting market research — could be construed as gathering state secrets.

And yet faced with a struggling economy and trade war with the U.S., officials such as Premier Li Qiang keep touting China’s openness to foreign investment. Even Xi has made superficially friendly gestures toward foreign chief executives and welcomed overseas students.

Left: Premier Li Qiang delivers a keynote speech at the opening of the China Development Forum, March 24, 2025. Right: A symposium on “New Trends in Economic Globalisation and Expanding Institutional Opening-up” held during the China Development Forum, March 24, 2025. Credit: China Development Forum

In March during the business-friendly China Development Forum, the Beijing Public Security Bureau released five Mintz Group employees it had detained in 2023 — a reassuring gesture. Days later the Ministry of State Security posted warnings about spying by foreign consultancies. Such dual messaging may at times be coordinated and intentional: bait and switch. Other times, the competing incentives of economic technocrats and securocrats produce incoherence and confusion.

Where foreigners see contradictions, the CCP reconciles them as behavioral conditioning. The legal uncertainty is deliberate. The Party wants everyone to restrain and censor themselves with proactive caution. In Perry Link’s memorable metaphor, it’s “the anaconda in the chandelier” — you never know when it might drop.

The takeaway: money, technology and insights are still welcome, but foreigners must tread carefully in an increasingly controlled and securitized landscape in which bad luck can bring personal tragedy. Scant weeks before my own abduction, I was an invited speaker at the PLA’s Xiangshan Forum. Today’s red-carpet guest can be tomorrow’s consular case.

Security bureaus have arbitrarily detained up to 200 Americans over the years, human rights group the Dui Hua Foundation has estimated. Since 2015 they have also arrested at least 17 Japanese citizens, including Hiroshi Nishiyama (the aforementioned Astellas executive) and Hideji Suzuki, a Sinophile who headed the Japan-China Youth Exchange Association before an overzealous Beijing State Security Bureau took six years of his life away. Citizens of at least 12 countries have suffered similarly.

If you’re affiliated with a government, non-profit, research, due diligence, or media organization, its more likely state and public security will flag you as a potential agent of influence or collector of intelligence. But that doesn’t mean businesspeople, teachers or tourists are risk-free.

Consider detained educators like Alabama’s David McMahon, Idaho’s Jacob Harlan and Alyssa Petersen, and travelers such as Louisiana-born Nelson Wells, Jr. and Illinois native Dawn Michelle Hunt. Diverse cases including Australian businessmen James Peng, Stern Hu and Matthew Radalj, American IHS Energy geologist Xue Feng, British corporate investigator Peter Humphrey and his countryman Ian Stones, Canadian missionaries Kevin and Julia Garratt, Texas business consultant Sandy Phan-Gillis, Taiwanese trader Morrison Lee, and last November, AstraZeneca’s China president Leon Wang, collectively illustrate the wide range of circumstances — and the similarities of their horrifying experiences.

In 2024, relentless diplomacy and prisoner swaps finally freed four Americans — David Lin, John Leung, Kai Li, and Mark Swidan — after long prison sentences. But that brief diplomatic breakthrough had no effect on China’s overall trajectory. Earlier this year Guangdong Province executed four Canadians its courts had sentenced earlier on narcotics charges. And in April, after the Philippines arrested Chinese citizens on espionage charges, Beijing detained three Filipino nationals and likewise accused them of spying — charges Manila denies.

Party-state secrecy and family privacy requests mean that uncounted numbers of other cases go unreported. Not all are political, of course. Reasons can range from actual violations of the law by the target, a relative, or acquaintance, to police overzealousness, personal revenge, corrupt shakedowns, or diplomatic opportunism. What’s clear is that when bilateral relations tank, ongoing cases move further from resolution.

Exit bans are not centrally imposed: multiple government entities can ask the Ministry of Public Security to enforce them at the border. This makes them prone to abuse not only for political leverage but also in civil and business disputes. Laws, detentions and exit bans are multi-purpose tools.

Anecdotal evidence suggests naturalized former PRC nationals may be at greater risk. China’s Nationality Law doesn’t allow dual citizenship, but the state nonetheless sometimes behaves as though it has residual authority over its ethnic diaspora. Consider the ordeals of Australian CGTN presenter Cheng Lei and writer Yang Hengjun, Arizona massage therapist Sue Jiang, Canadians Huseyin Celil, John Cheng, Li Yonghui, Peter Wang and Ruqin Zhao, North Carolina pastor John Cao, Swedish publisher Gui Minhai, and Japan-based academics Fan Yuntao, Hu Shiyun and Yuan Keqin.

Chinese citizens who meet foreigners or do media or research work for them also face elevated risks. A recent example is consultant Emily Chen, detained last year in Dalian while working for Safe Ports. A conversation can spark accusations of leaking state secrets. Last November, respected journalist Dong Yuyu was sentenced to seven years, ostensibly for speaking with diplomats. Other Chinese reporters and researchers detained in recent years include Die Zeit’s Zhang Miao, Bloomberg’s Haze Fan, the South China Morning Post’s Minnie Chan, and Gusa Press editor Li Yanhe. In total, China is currently imprisoning at least 50 media professionals, the Committee to Protect Journalists says — the most in the world.

As the latest incident with Wells Fargo’s Mao Chenyue illustrates, exit bans—which can involve interrogation — are also a growing concern. Dui Hua estimates dozens of Americans have been barred from leaving — as have over 100 other nationals. Recent cases include Irish businessman Richard O’Halloran, Seattle couple Jodie Chen and Daniel Hsu, Chinese-American siblings Cynthia and Victor Liu, Kroll manager Michael Chan, Nomura banker Charles Wang Zhonghe, a UBS Group wealth manager, and last fall a Chinese-American Koch Industries executive.

The Party-state seems to be increasing its use of exit bans, which violate human rights, particularly to coerce overseas Chinese. They conveniently create a “Hotel California” effect for unwary visitors that attracts less attention than detention while offering more ambiguity and plausible deniability. Exit bans are legally unclear and not centrally imposed: multiple government entities can ask the Ministry of Public Security to enforce them at the border. This makes them prone to abuse not only for political leverage but also in civil and business disputes. Laws, detentions and exit bans are multi-purpose tools.

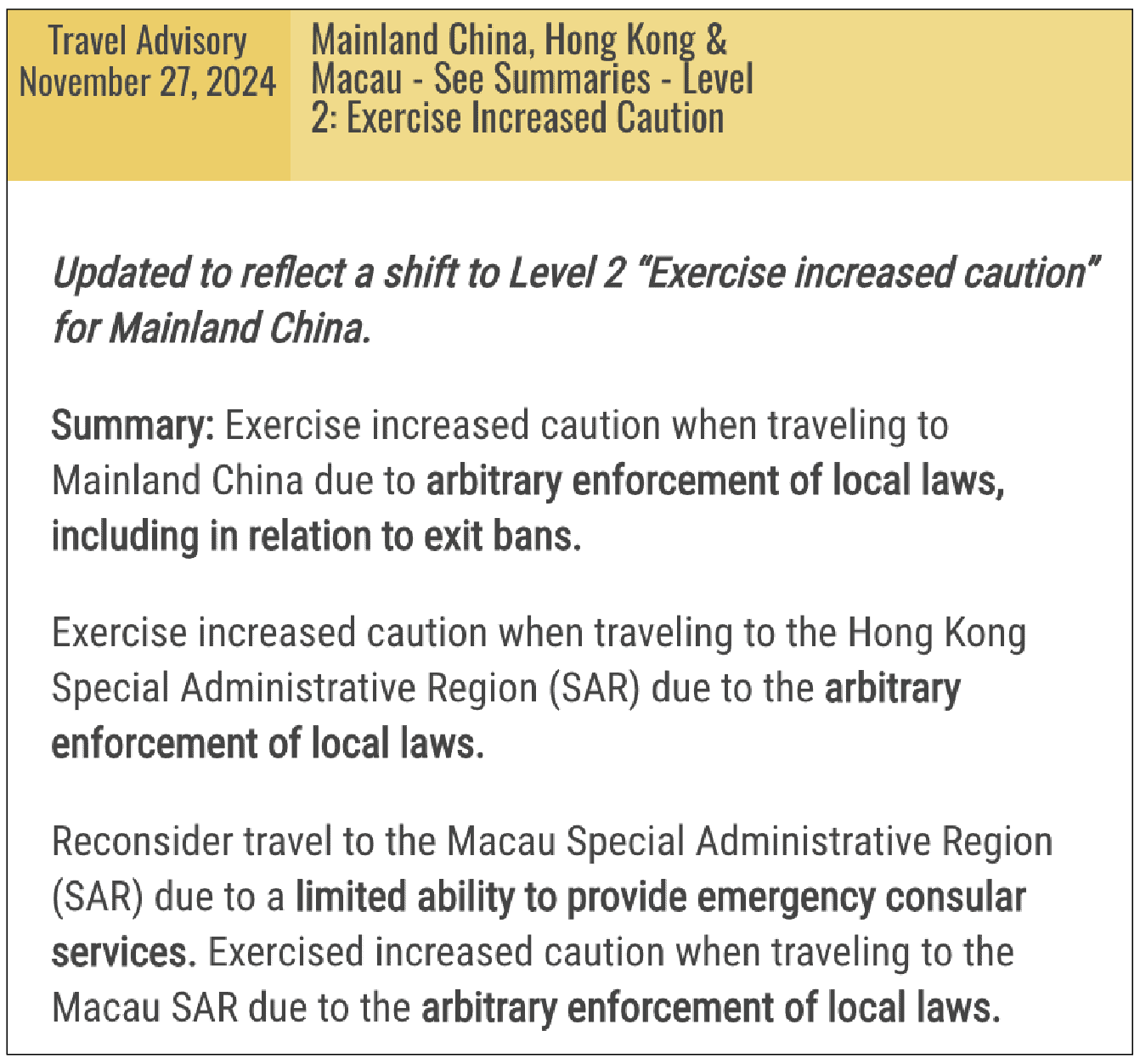

You needn’t take my word for it. Read government travel advisories. The U.S. State Department says you should “exercise increased caution when traveling to Mainland China due to arbitrary enforcement of local laws, including in relation to exit bans.” Other governments have similar warnings1Australia: https://www.smartraveller.gov.au/destinations/asia/china, Canada: https://travel.gc.ca/destinations/china, France: https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/conseils-aux-voyageurs/conseils-par-pays-destination/chine/#securite, Japan: https://www.cn.emb-japan.go.jp/consular_j/joho120220_j.htm, Taiwan: https://apnews.com/article/china-taiwan-safety-warning-af2bb9e74087acfef1f6c8677326d6d6, UK: https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/china/safety-and-security, as does OSAC’s China page. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention also has concluded that there is a “systemic problem with arbitrary detention in China, which amounts to a serious violation of international law.”

How to Prepare for the Worst

Given the above, what should anyone contemplating a business or other visit do to prepare? Here, I can offer some practical tips. But remember, the risk is binary: once you cross the border, you’re in their power.

First, know before you go. Consult experts and analyze others’ experiences. Prepare for worst-case scenarios. Read human rights NGO Safeguard Defenders’ new handbook Missing in China. It also has excellent advice on how to help those already detained.

China’s Orwellian system of Residential Surveillance in a Designated Location (zhiding jusuo jianshi juzhu) entails up to six months of secret detention without legal counsel, solitary confinement, relentless interrogation, and coercion to confess to crimes. Once arrested and formally detained, interrogation can continue for many more months. Pretrial detention can last years. With an over 99 percent conviction rate, a prison sentence is virtually certain, often involving forced labor and limited consular access or communication with family. Chinese courts sometimes apply the death penalty to foreigners, even for non-violent crimes.

Weigh the risks and rewards. Will your Chinese interlocutors provide information and insights that would be otherwise unobtainable? That’s exactly what the counter-espionage law is designed to curtail.

Unless you knowingly and deliberately break the law, your odds of being detained are extremely low. But how low does the probability have to fall, and how great do the potential benefits need to be to justify a catastrophic risk? If there’s a 1 in 1,000 chance you could be psychologically tortured and confined for several years, how willing are you and your loved ones to test those odds for a few opinions, impressions and Peking duck dinners?

I say this with deep dismay. The numbers of Westerners in China or learning Chinese have fallen dramatically at a critical time when we need more than ever a deeper understanding of the country and the moderating influence of personal relationships.

…in the dystopian reality of the Party-state’s panopticon, anyone intending to have substantive interactions with Chinese counterparts must hope that the omnipresent surveillance apparatus doesn’t notice or object, and that the CCP maintains an attitude of political benevolence.

If you go, be sure to travel on the proper visa, or PRC authorities will have an automatic justification to detain you. Inform your embassy of your travel plans and set clear communication protocols with family and colleagues. Imagine the implications if you were abruptly extracted from your life and make contingency plans including powers of attorney and instructions for managing your personal and financial affairs. Take extensive IT security precautions. Remember that Chinese police can inspect your electronics at any time. A VPN improves privacy but is technically illegal without a permit.

Your decision isn’t just personal — it carries symbolic weight and ethical implications. Every foreign visitor sends a signal about whether we’re normalizing Beijing’s increasingly repressive approach to international engagement, or maintaining solidarity on rule of law, human rights and standards of acceptable behavior.

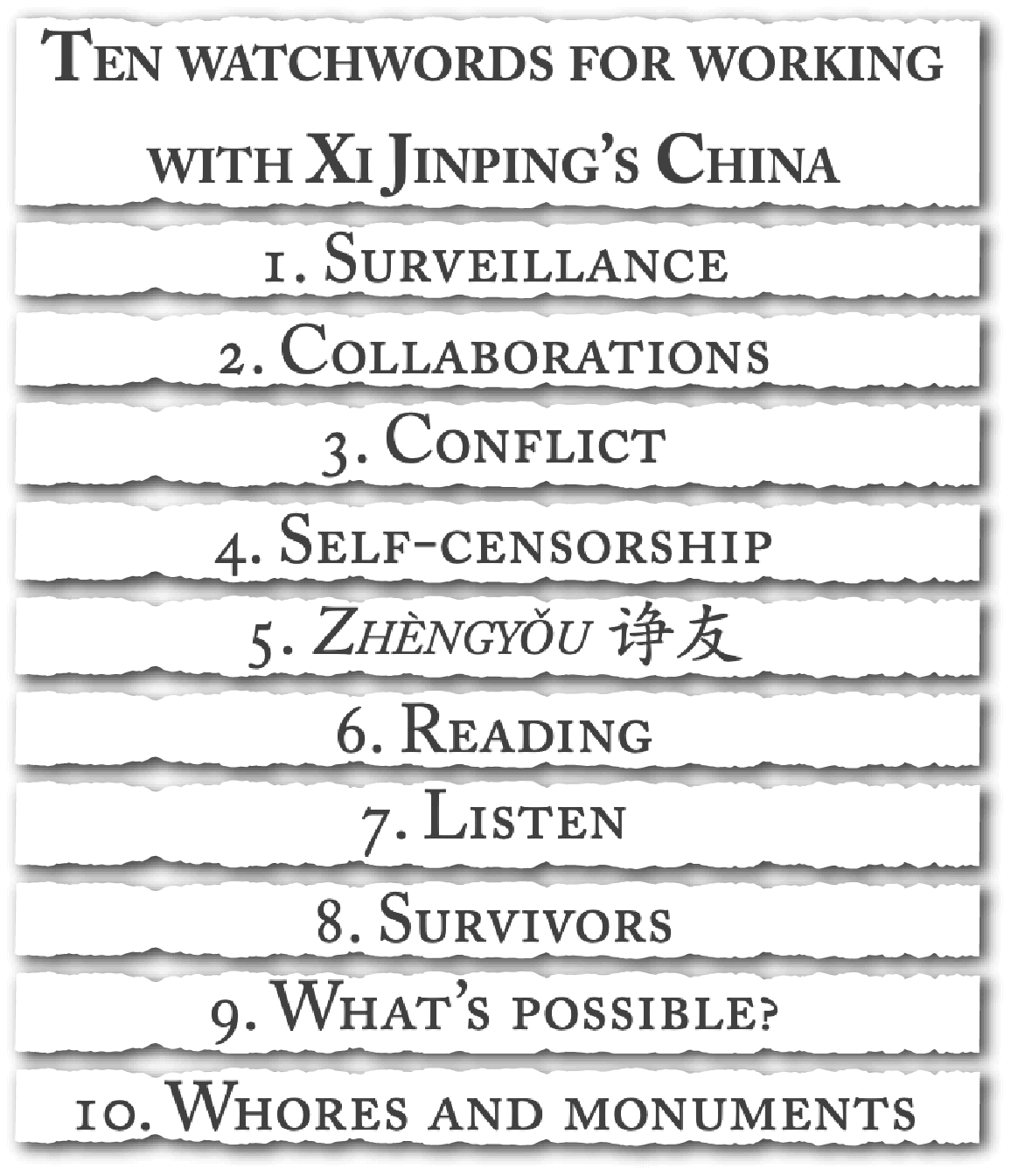

Learn and follow Professor Geremie Barmé’s “ten watchwords for working with Xi Jinping’s China.” Reflect on whether you have a responsibility to raise human rights concerns. Beyond the abovementioned foreign citizens, the Party-state is holding over 40,000 Chinese political prisoners. Advocate for their release.

Engage in dialogue if you can, but don’t acquiesce to gaslighting or shrink from refuting and correcting disinformation. Convey your objections to China’s mass human rights violations, use of arbitrary detention and sanctioning of parliamentarians, researchers, non-profits and think tanks. At least don’t be a useful idiot whose visit or study abroad is used as propaganda, particularly in Xinjiang.

In an ideal world, travel to China would be about getting to know the fascinating country and its extraordinary people in all their complexity and diversity, building trust and correcting misperceptions. But in the dystopian reality of the Party-state’s panopticon, anyone intending to have substantive interactions with Chinese counterparts must hope that the omnipresent surveillance apparatus doesn’t notice or object, and that the CCP maintains an attitude of political benevolence. There are no such guarantees.

Welcome to China. Hope you survive the New Era.

Michael Kovrig is Executive Director of StrategicEffects, a nonprofit research network, Chief Executive of Kovrig Group, and Senior Adviser, Asia to the International Crisis Group. A former diplomat, he lived in China from 2014–2021. He is writing a book on China and geopolitics. Substack, LinkedIn, @MichaelKovrig, @kovrig.bsky.social.