Bonnie S. Glaser is the managing director of the Indo-Pacific Program at the German Marshall Fund of the United States. She was previously a senior adviser for Asia and the director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Ryan Hass is director of the John L. Thornton China Center and the Chen-Fu and Cecilia Yen Koo Chair in Taiwan Studies at the Brookings Institution. From 2013 to 2017, Hass served as the director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia at the Na

LISTEN NOW

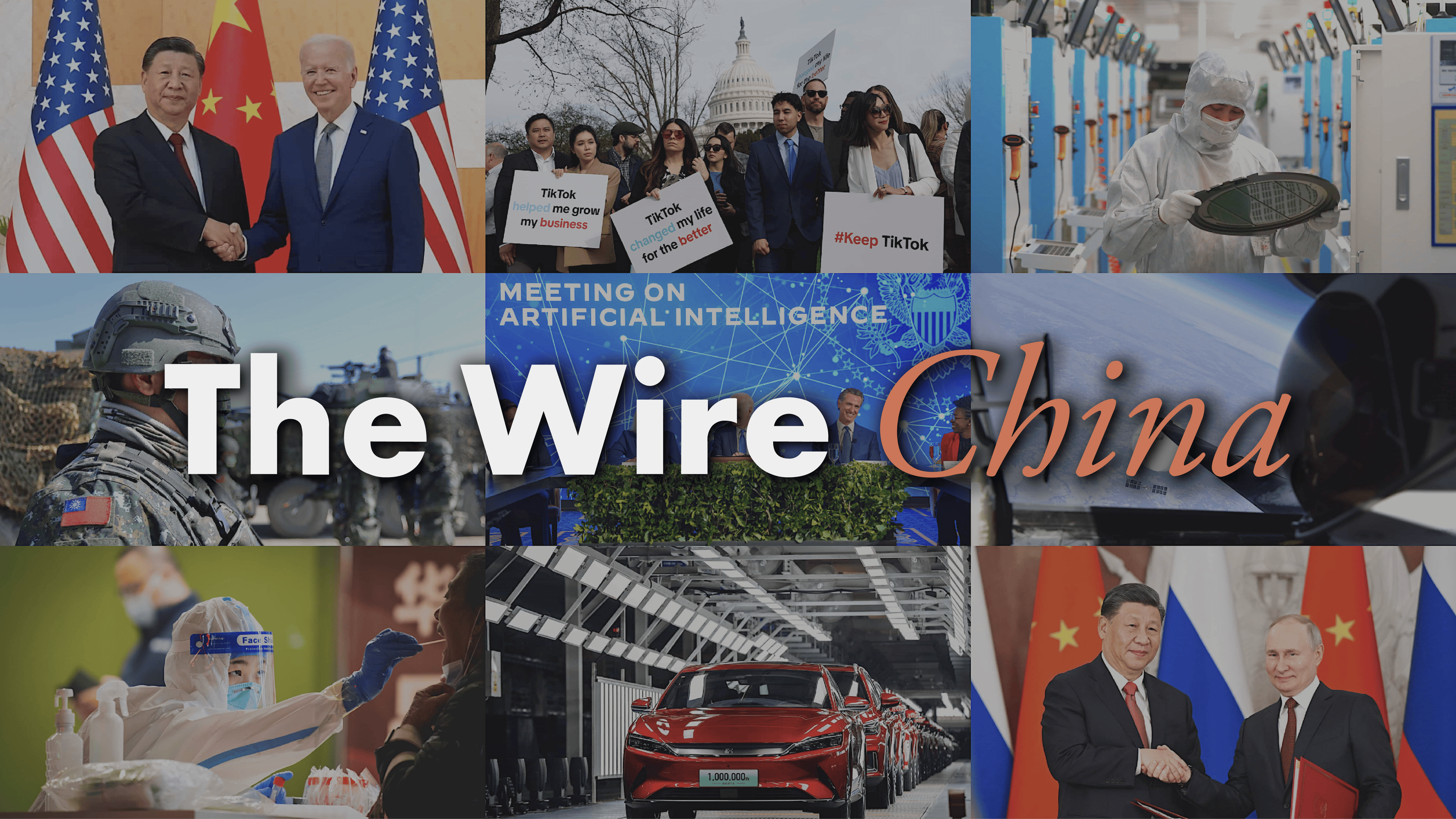

Face-Off: U.S. vs. China

A podcast about how the two nations,

once friends, are now foes.