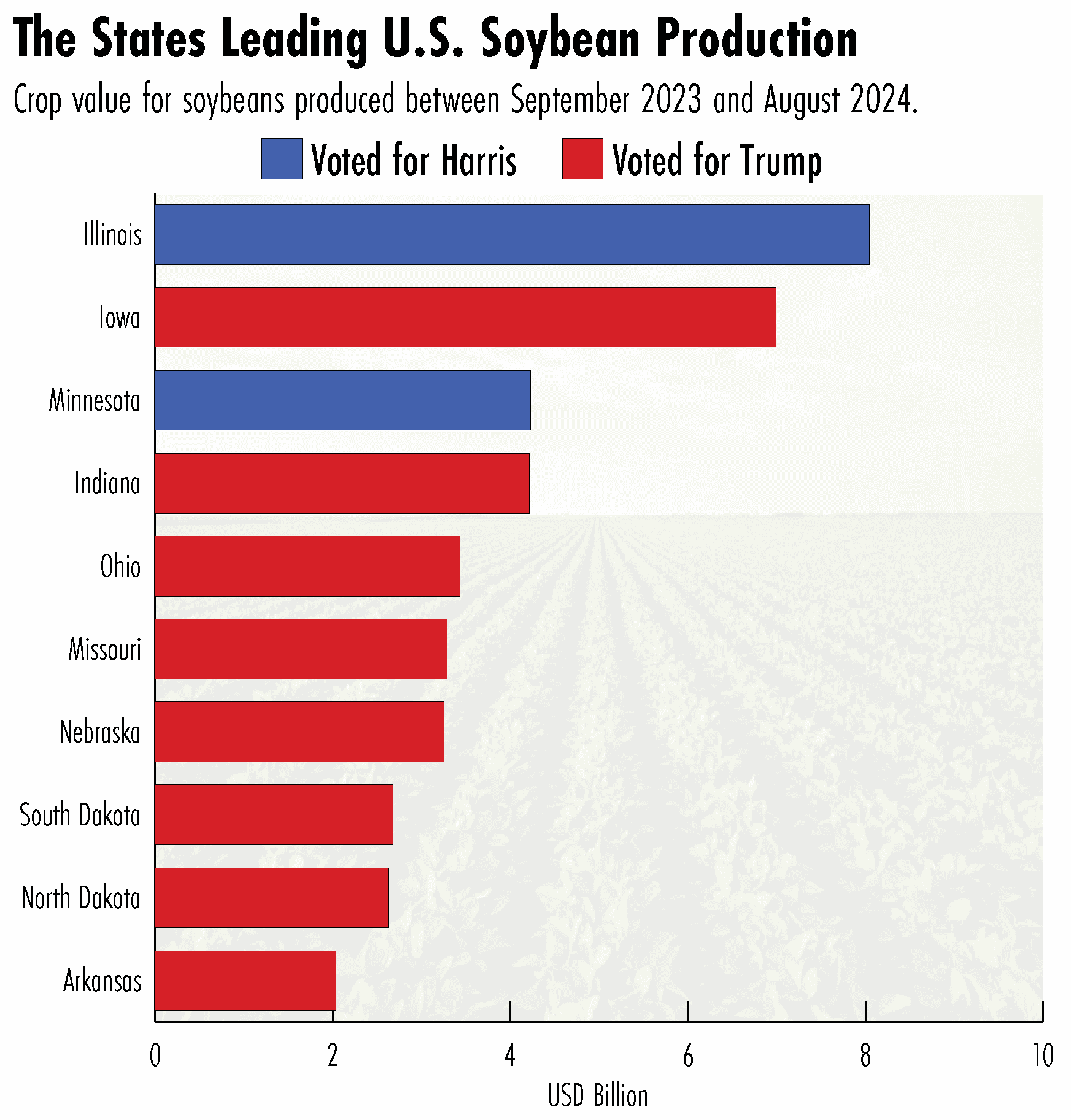

The Trump administration’s trade war redux has landed in America’s heartland. Chinese buyers have halted purchases of several U.S. agricultural products, prompting a crisis for farmers as the harvest season for soybeans, a major export, approaches.

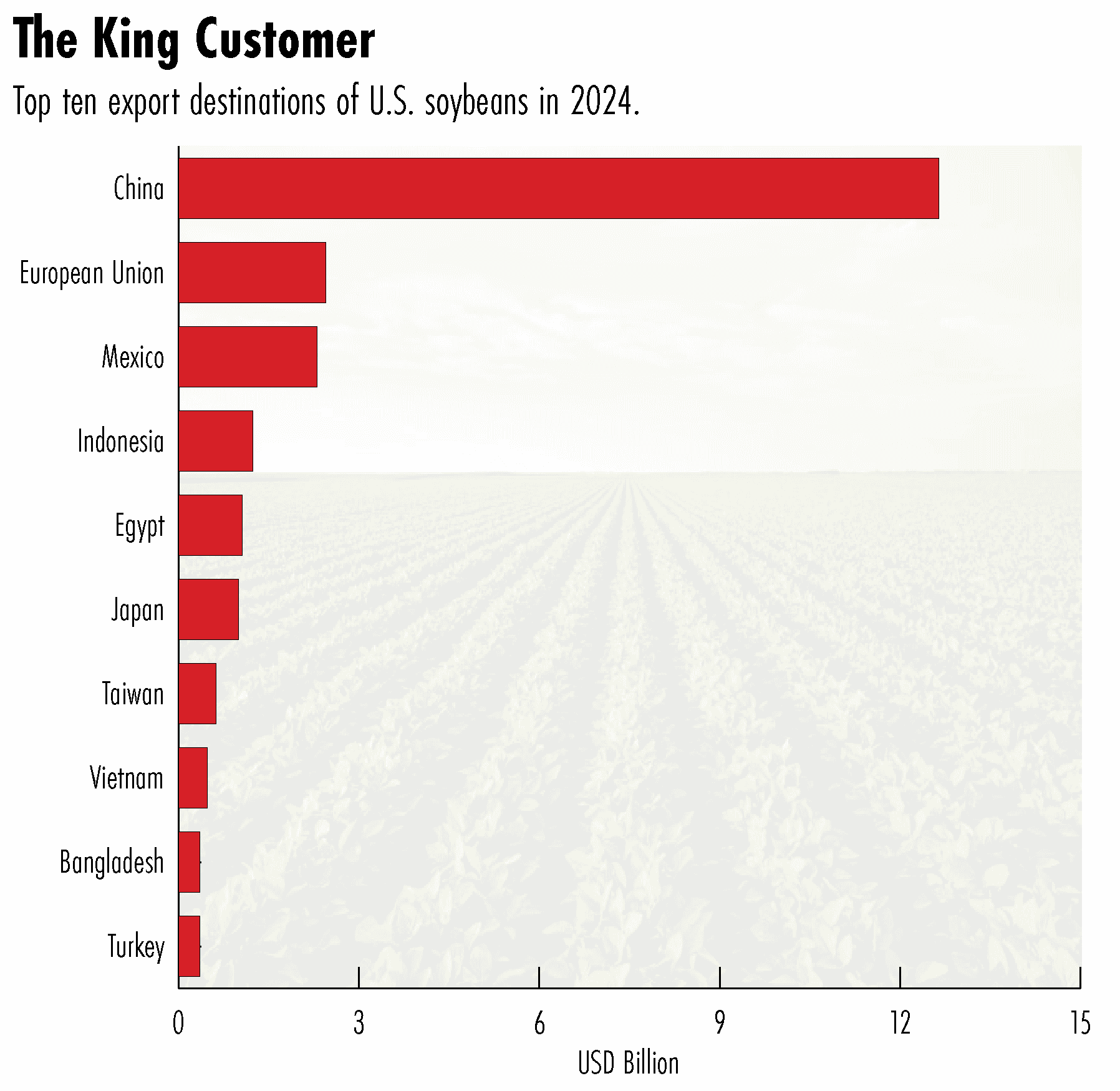

Every year since 2020 China has bought more U.S. soybeans than all other countries combined, adding up to $74 billion in purchases over that time, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But this year the U.S. has not exported any soybeans to China since May, leaving farmers in limbo.

“There is no buyer that can replace China,” says Matthew Kruse, president of Iowa-based brokerage Commstock Investments. “Our greatest fear is being realized. We’re losing our biggest customer.”

The scale of potential disruption was set to come to a head last week. President Trump had prepared a multibillion aid package for U.S. farmers, but reportedly delayed the plan due to the government shutdown in Washington. Many farmers are based in states that voted for Trump during last year’s election.

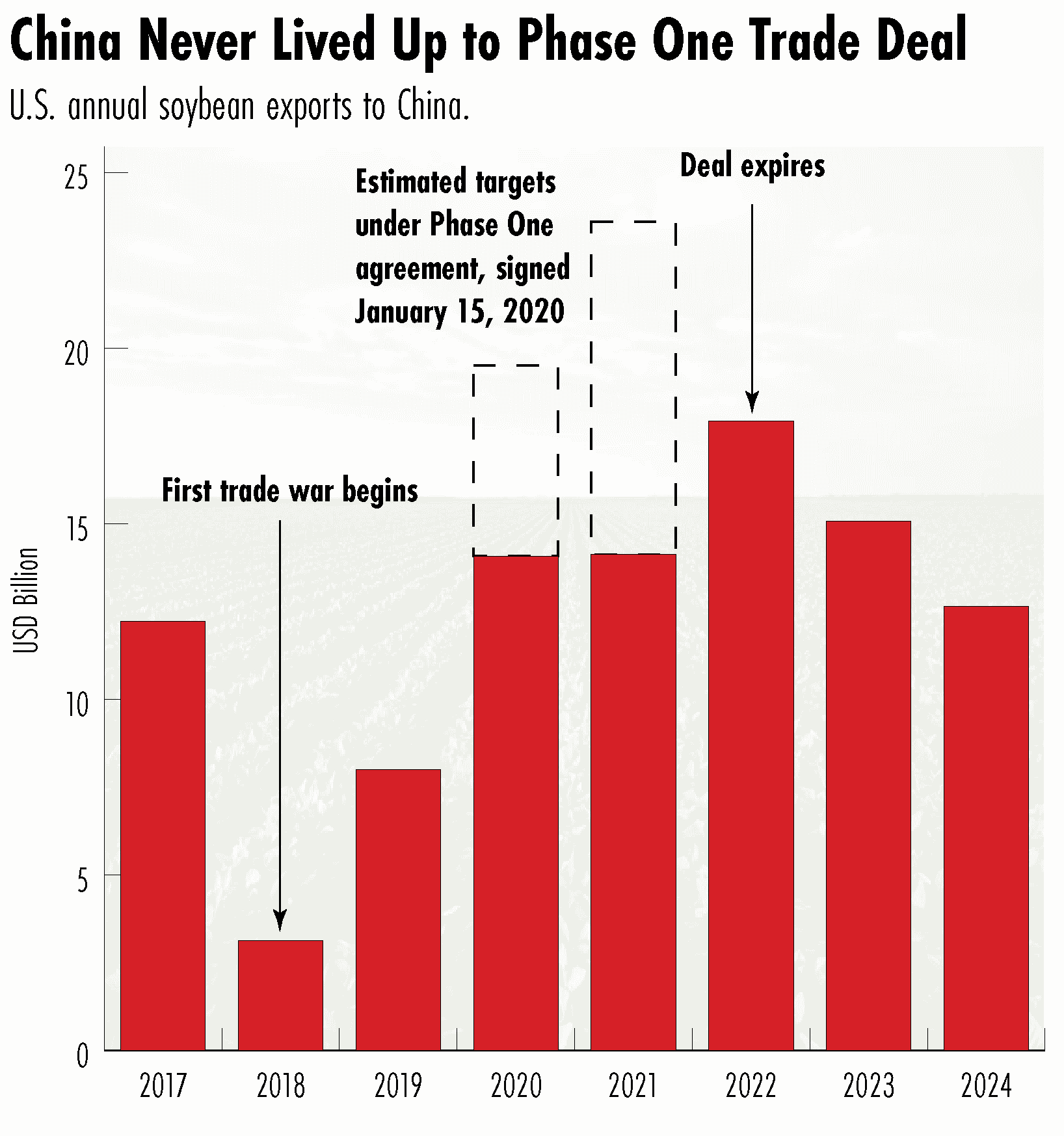

China’s buying freeze mirrors the tactics Beijing deployed in 2018, when Trump launched a trade war during his first term in office. China’s purchases of soybeans fell by 75 percent that year, leading Trump to announce a bailout for farmers that the Government Accountability Office later valued at $23 billion.

Farmers in the industry have been aware for a long time that we’re highly dependent on China, but either through lack of leadership or lack of government incentives, no one ever did anything about it.

Matthew Kruse, president of Iowa-based brokerage Commstock Investments

China appeared set to boost purchases of soybeans when Washington and Beijing agreed to a trade deal in January 2020, the so-called Phase One Trade Agreement. But the arrangement quickly fell apart amid the disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic and criticism that the Biden administration did not prioritize enforcing it. As a result China never followed through with its pledge to buy at least $80 billion in U.S. food, seafood and agricultural products over two years. American soybean exports to China in 2024 were just 3.4 percent higher than in 2017.

The U.S. has made few efforts to diversify its customer base in the years since. As recently as last year, China still bought more than half of all American soybean exports.

“Farmers in the industry have been aware for a long time that we’re highly dependent on China, but either through lack of leadership or lack of government incentives, no one ever did anything about it,” Kruse says.

China has meanwhile diversified its suppliers. Brazil, which previously sold a similar amount of soybeans to China as the U.S. did, is now by far the largest source country for the Chinese market. Brazil has supplied 71 percent of China’s soybean imports so far this year, compared to slightly more than half in 2017, according to data from China’s General Administration of Customs.

The result is both a major opportunity and a significant risk for Brazil, says Alexandre Lima Nepomuceno, head of soybean research at Embrapa, a state-owned research group backed by the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture.

“The Brazilian firms are happy, but I keep saying we should be careful,” he says. “There is a huge dependence.”

The winner in all this appears to be China. It does not grow enough soybeans to meet domestic demand for the oilseed, which it mostly crushes into animal feed to support its pork industry. The country is currently paying less for the imports it needs — increased global production has brought soybean prices to near a five-year low — as it holds the promise of resumed purchases as a carrot in trade negotiations with Washington. Trump said on social media earlier this month that he planned to talk to Chinese President Xi Jinping about the issue, but on Friday wrote that Beijing’s recent rare earth controls gave the two men “no reason” to meet.

Even if the two leaders make a deal, it will be too late for this year’s crop because Chinese imports are seasonal, says Darin Friedrichs, managing director of research firm Sitonia Consulting, which focuses on Chinese agricultural markets.

China’s ability to go without buying U.S. soybeans this far into autumn is “unprecedented,” he adds. “Beijing is just in a very good position this time around.”

Noah Berman is a staff writer for The Wire based in New York. He previously wrote about economics and technology at the Council on Foreign Relations. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe and PBS News. He graduated from Georgetown University.