Yao Yang is one of China’s leading economists. As dean of Peking University’s National School of Development and director of the school’s Center for Economic Research, Yao has put a priority on research to further China’s economic and political development. As he explains in the interview below, top academics in China have a closer relationship with the government than do similar academics in the U.S. He is a member of the Chinese Economist 50 Forum, whose members often play significant

LISTEN NOW

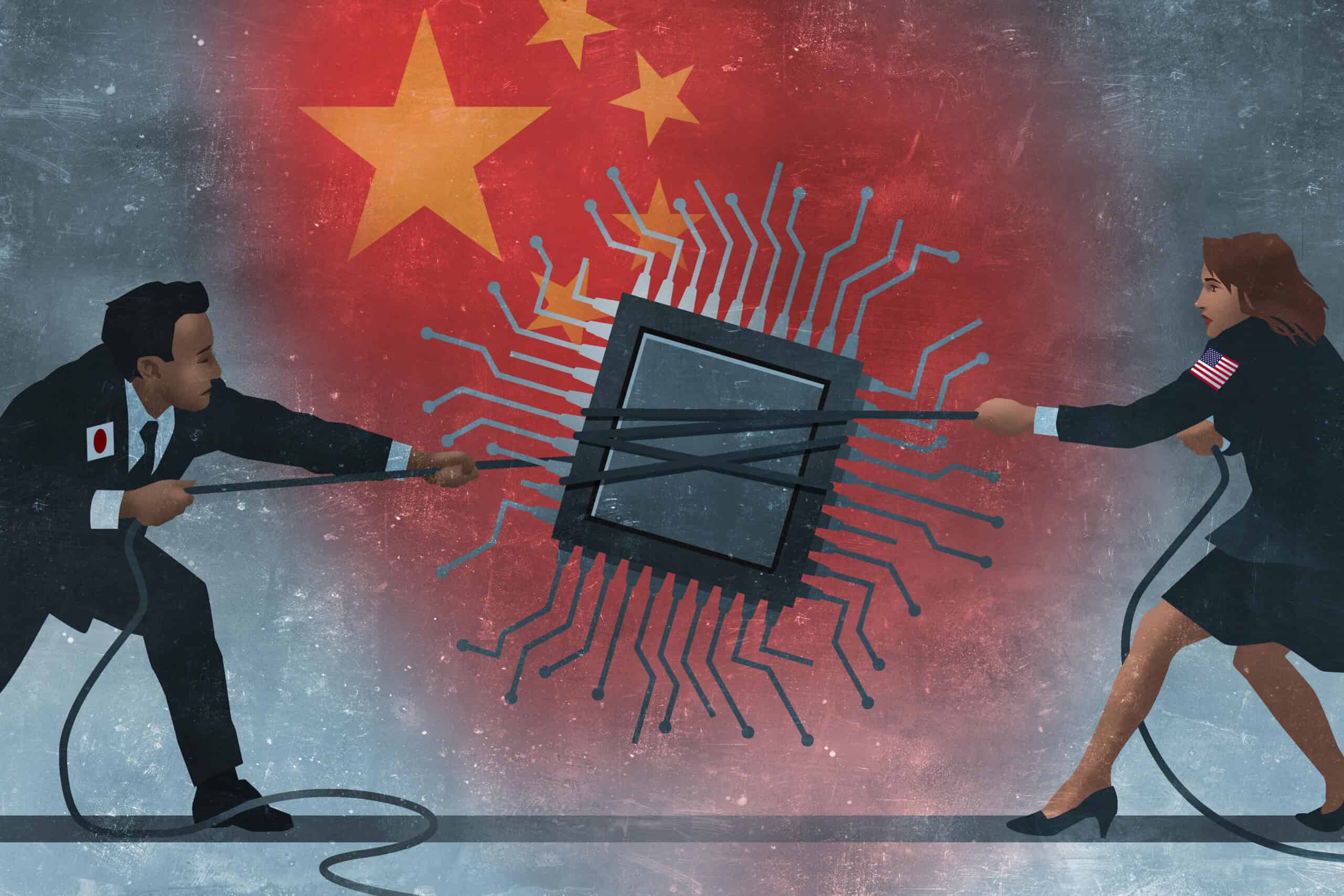

Face-Off: U.S. vs. China

A podcast about how the two nations,

once friends, are now foes.