Bonnie S. Glaser is director of the Asia Program at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, where she focuses on China’s foreign and security policy. Before that, she was a senior adviser for Asia and director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. She is also a nonresident fellow with the Lowy Institute in Sydney, Australia. Glaser has also served as a consultant for the State Department and the Department of Defense. She has a B

LISTEN NOW

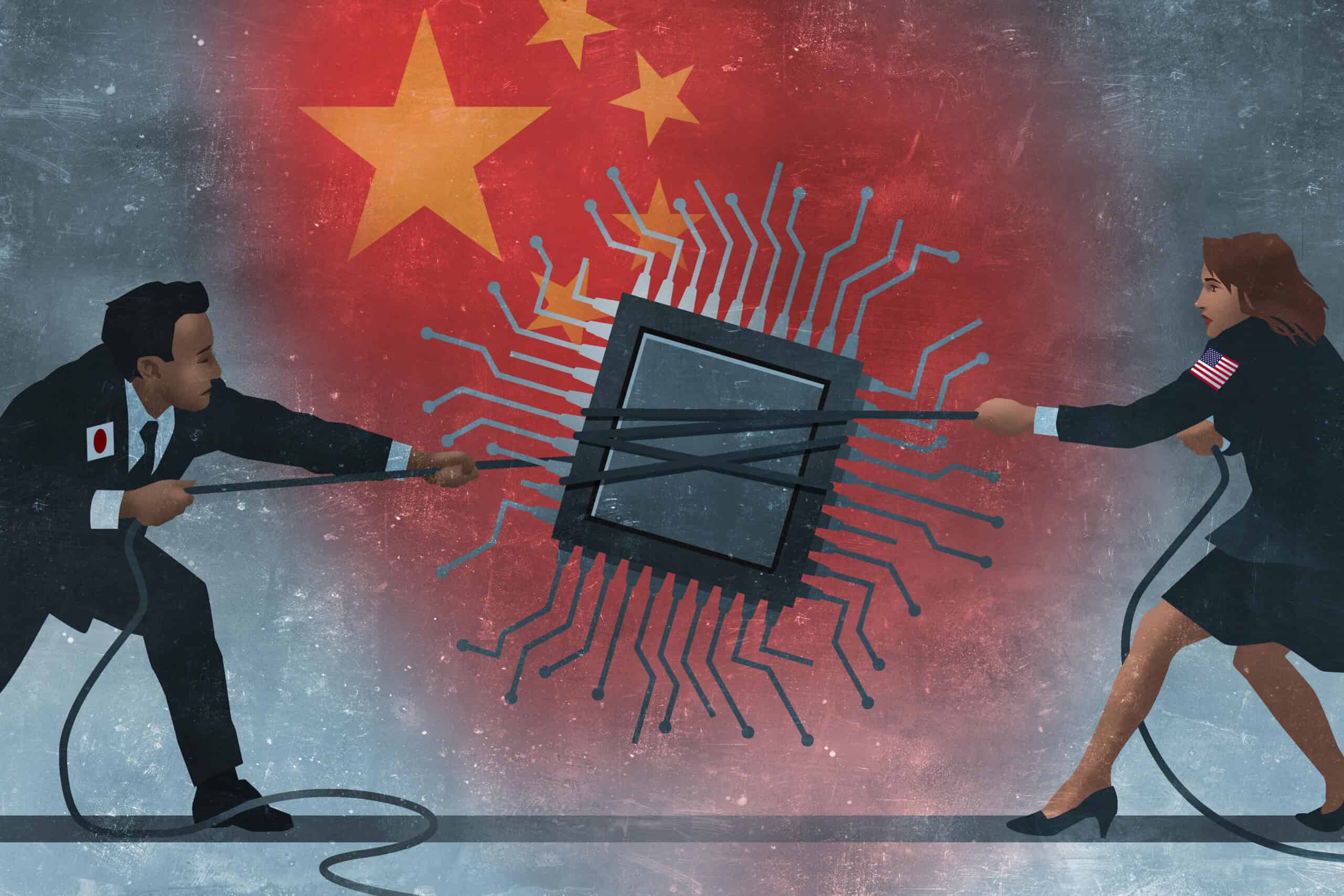

Face-Off: U.S. vs. China

A podcast about how the two nations,

once friends, are now foes.