General (Ret.) Joe Dunford served as the 19th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, from 2015-2019. In that capacity, he was the senior ranking U.S. officer and the principal military advisor to the President, Secretary of Defense, and the National Security Council. Prior assignments included service as the Commandant of the Marine Corps and the Commander of U.S. Forces and NATO Forces in Afghanistan. He is a graduate of St Michael’s College and has graduate degrees from Georgetown University

LISTEN NOW

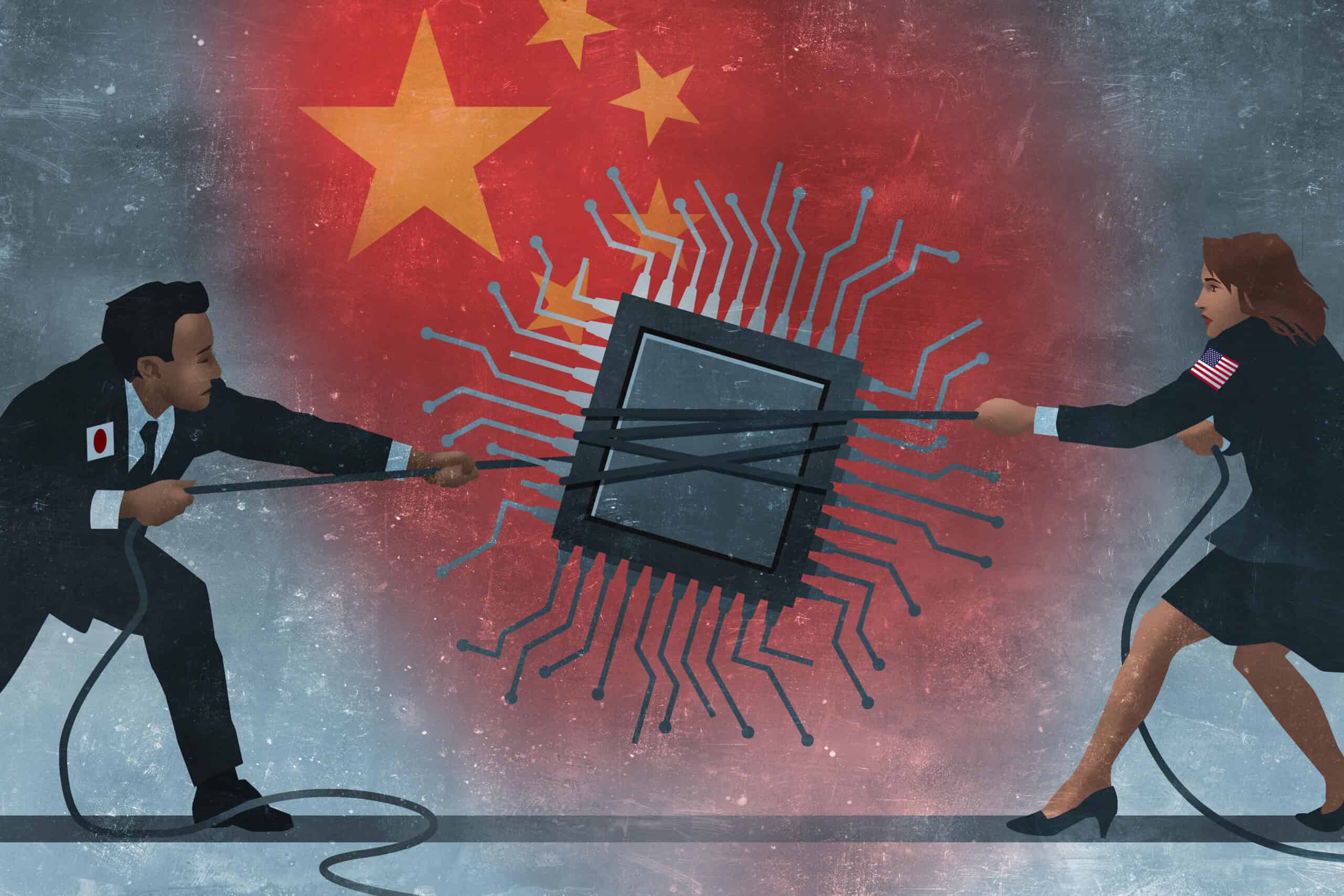

Face-Off: U.S. vs. China

A podcast about how the two nations,

once friends, are now foes.