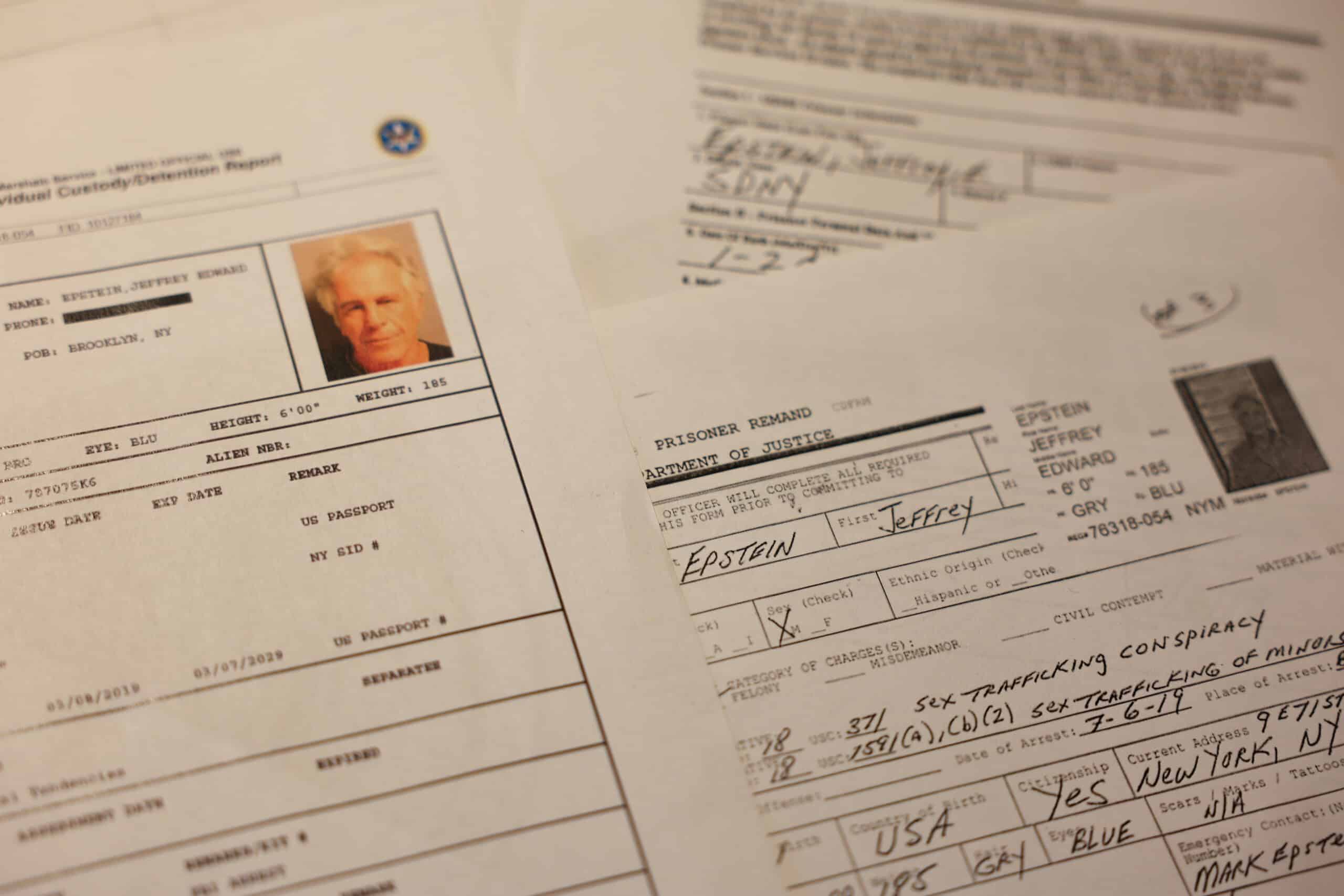

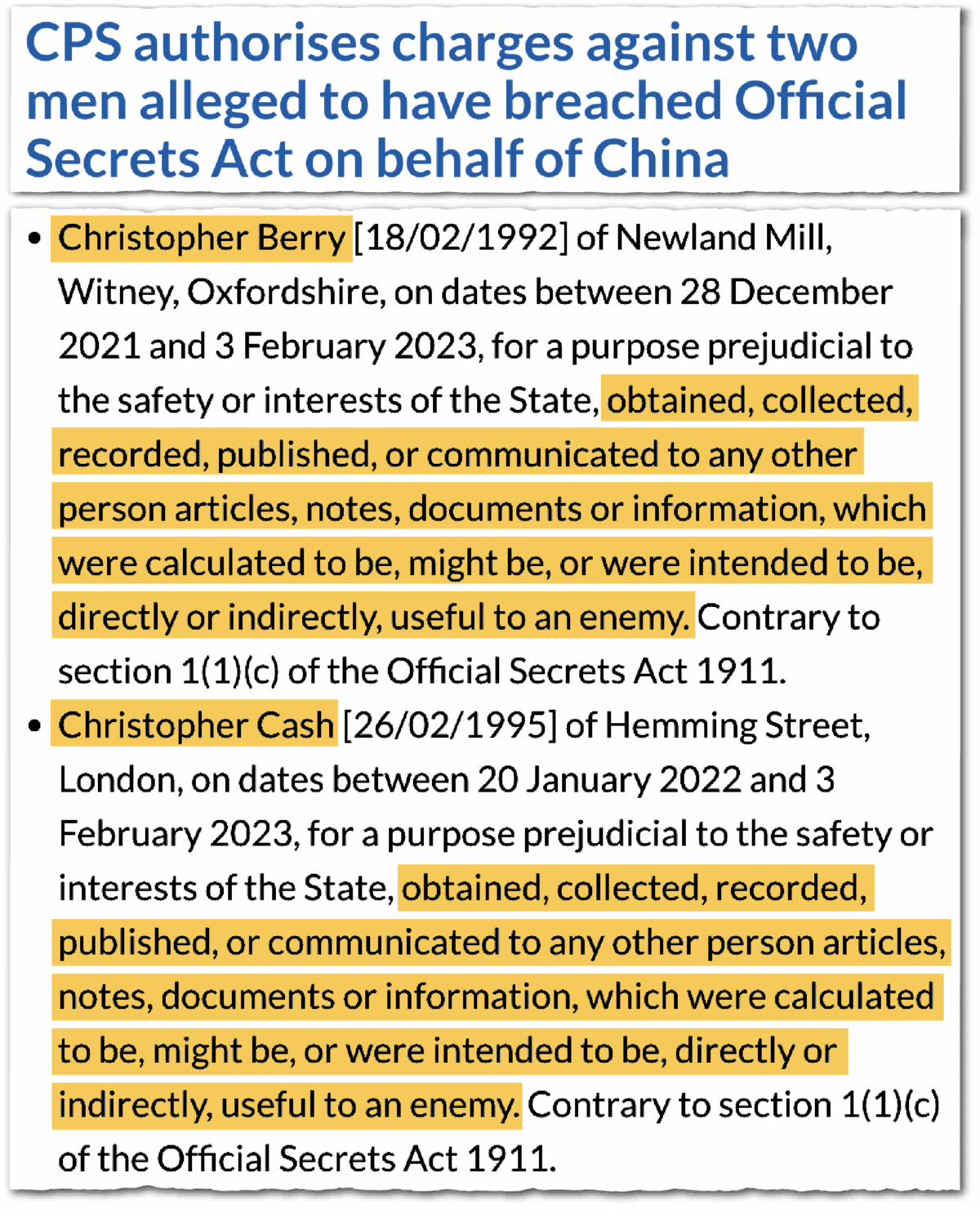

When the U.K.’s Crown Prosecution Service — the agency that brings criminal cases on behalf of the government — announced in April 2024 that it had arrested two British men for alleged acts of espionage with Chinese agents the news provoked intense media scrutiny at home and abroad. The formal indictment stated that Christopher Cash and Christopher Berry had been ‘charged with providing prejudicial information to a foreign state’.

Many commentators, while refraining from labeling the accused pair as fully convicted, did not hold back in their use of innuendo. For them it was clear that something untoward was going on at the heart of the British political establishment, and that China was the chief culprit standing behind it all. Cash’s job as a parliamentary researcher who worked with prominent politicians engaged in China policy has aroused particular scrutiny.

Almost 18 months later, and just weeks before the trial was due to begin, the charges against Cash and Berry were suddenly dropped last week: on reviewing the evidence, prosecutors were not convinced they had sufficient material to secure a conviction. This action is not the same as clearing the two accused, but does indicate that they have been given the benefit of the doubt. Both men had claimed they were innocent all along.

Inevitably a matter like this stirs up deep emotions. If anything, the media furore following the case’s collapse has been more intense than the one around the time of the initial arrest. At this point I should declare my own interest in the case: I had been due to appear as an expert witness for Berry during the trial, though only talking about Chinese internal politics, international relations and matters purely pertaining to such areas.

China, under its current Communist-run government, is clearly ideologically unaligned with a multi-party democracy like Britain’s. Moreover, in the space of a generation, it has gone from having a smaller economy to the UK’s, to one that now stands five times larger. It has built up a formidable military and is, according to some reports, one of the most active states when it comes to gathering information in cyberspace.

The logic of stating China is an enemy state would mean cutting Britain off from economic opportunities that matter to our prosperity, and being involved in critically important engagements with new Chinese research and development on health, climate and the environment…

The clear cultural and values difference between China and Britain creates yet more space for misunderstanding and, for some, fear and anxiety. The idea of Chinese agents, working for organizations like the United Front, seeking to influence and manipulate the British government, has deep traction and is the subject of almost daily claims and speculation.

It would indeed be strange if such a powerful and significant country — one with interests over Taiwan, its own region, and global governance that differ so much from those of the political West — were not trying to exert some influence overseas, and undertaking some covert campaigns. After all, every country is to some extent interested in what others are up to, particularly when there are obvious mutual disagreements.

But being clear about what sort of threat countries like the UK are facing, and what to do about it, is a far more valuable way to counter the problem than harboring a general feeling of panic and uneasiness.

One of the controversies around the dropping of the Cash-Berry case surrounds the part politics may or may not have played in what has transpired. The debate here centers on whether the two accused could or should have been accused of colluding with an ‘enemy state’ — and whether that framing would in turn cause offence to China once it went to public trial.

The allegation now being made by government critics is essentially that officials may have pressed for the case to be dropped to avoid this potential embarrassment, preserving the UK’s commercial interests with China at a time when the country is crying out for investment in its economy even if at the expense — allegedly — of its national security. According to BBC reporting, the head of the CPS said on Tuesday this week that it had ‘tried to obtain further evidence from the government “over many months” but witness statements did not meet the threshold to prosecute.’

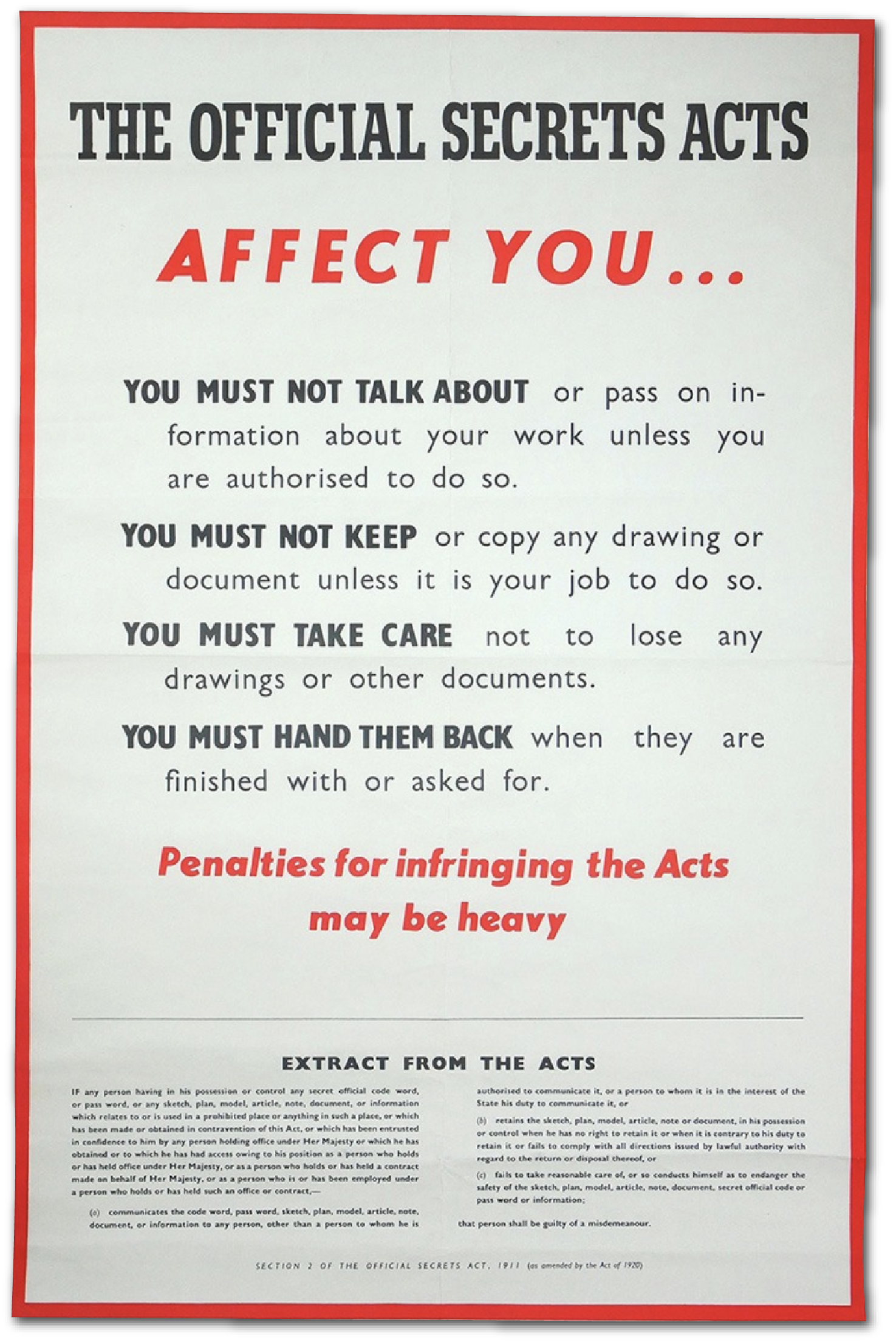

Here, things get technical. One of the special features of this case was that it is possibly the last to have been initially carried forward under the Official Secrets Act, which dates back more than a century, to 1911. That was repealed with the passing of more precise and updated legislation in the form of the National Security Act in 2023.

Cash and Berry’s alleged crimes were committed before this new law was on the statute books, even though their prosecution was to have occurred afterwards.

The 1911 act was from another age, and had language that was open to multiple interpretations — one of the reasons for its repeal. In its preamble, it states that people could be arraigned under it for gathering and then passing information that ‘might be or is intended to be directly or indirectly useful to an enemy.’

Partly thanks to its imprecise language, the 1911 act has a patchy history when it comes to being used to try to catch claimed spies. Perhaps most famously in 1985, its deployment against star civil servant Clive Ponting for leaking official classified information about the 1982 Falklands War to a Member of Parliament was turned down by a jury. More recently, however, it did succeed when used against a group of Bulgarians who were convicted of working for Russia in early 2025.

In the case of the Bulgarians, it is highly plausible to argue that Russia, through its attack on Ukraine in 2022 and the way that war indirectly involves NATO, is an enemy of the UK.

But Britain is not at the moment in any similar overt military engagement with China and, despite tensions over Taiwan, is not likely to be so any time soon. Indeed, since the Second Anglo-Chinese War from 1856 to 1860, Britain and China have not fought each other (although in the Korean War of 1950-53, Britain was part of the UN force fighting against North Korea, which was supported by significant Chinese forces). They were even allies in both the First and Second World Wars.

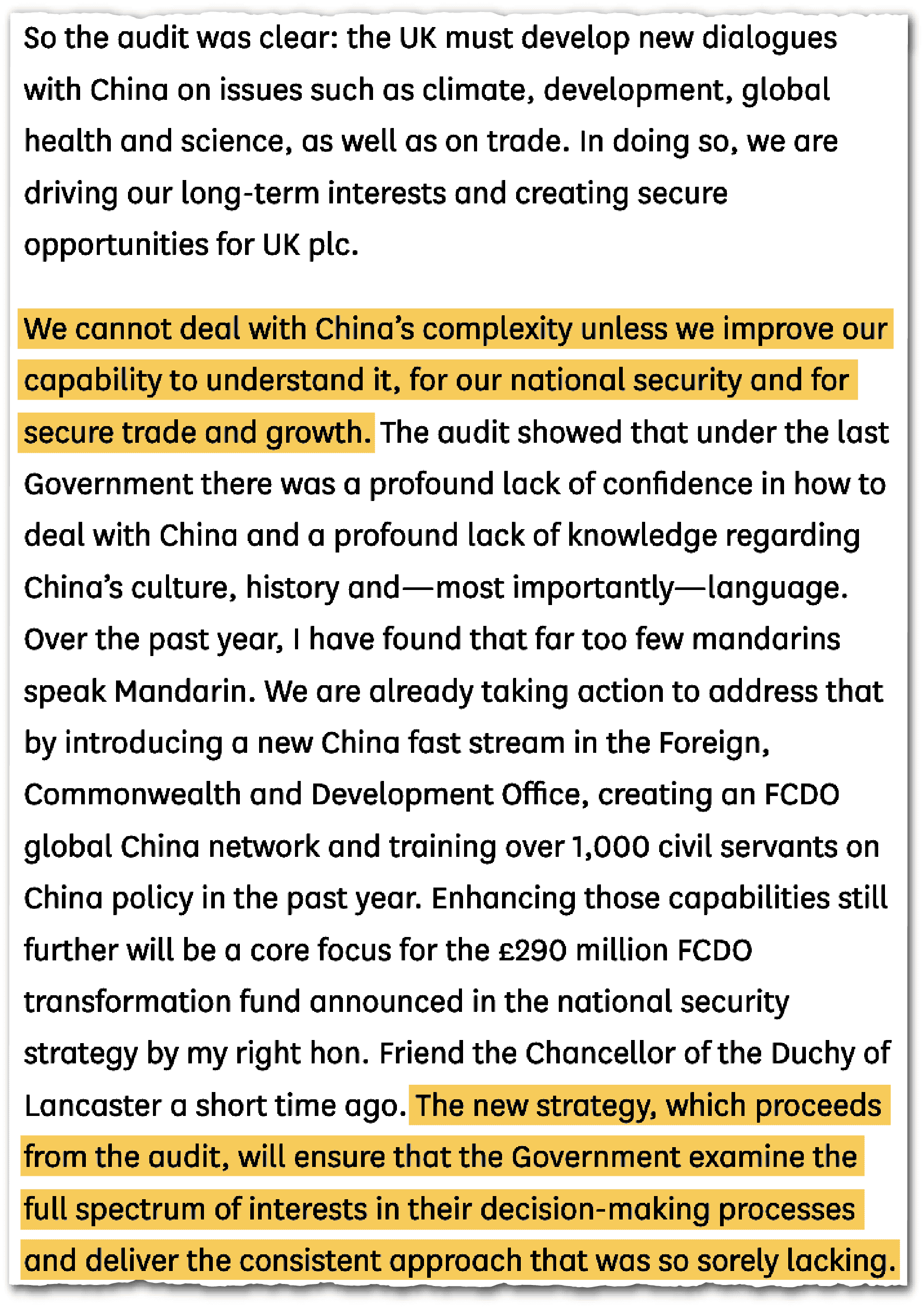

In more recent times, successive British governments have labeled the People’s Republic as a competitor, and, in some cases, an adversary — but the language used has never veered towards suggesting it is an enemy, actual or potential. The previous British government, led by former prime minister Rishi Sunak, published a major overview of British foreign policy in 2022-3 which did not hold back on the areas where relations with China were problematic. But nor did it raise these to ones where outright conflict was possible.

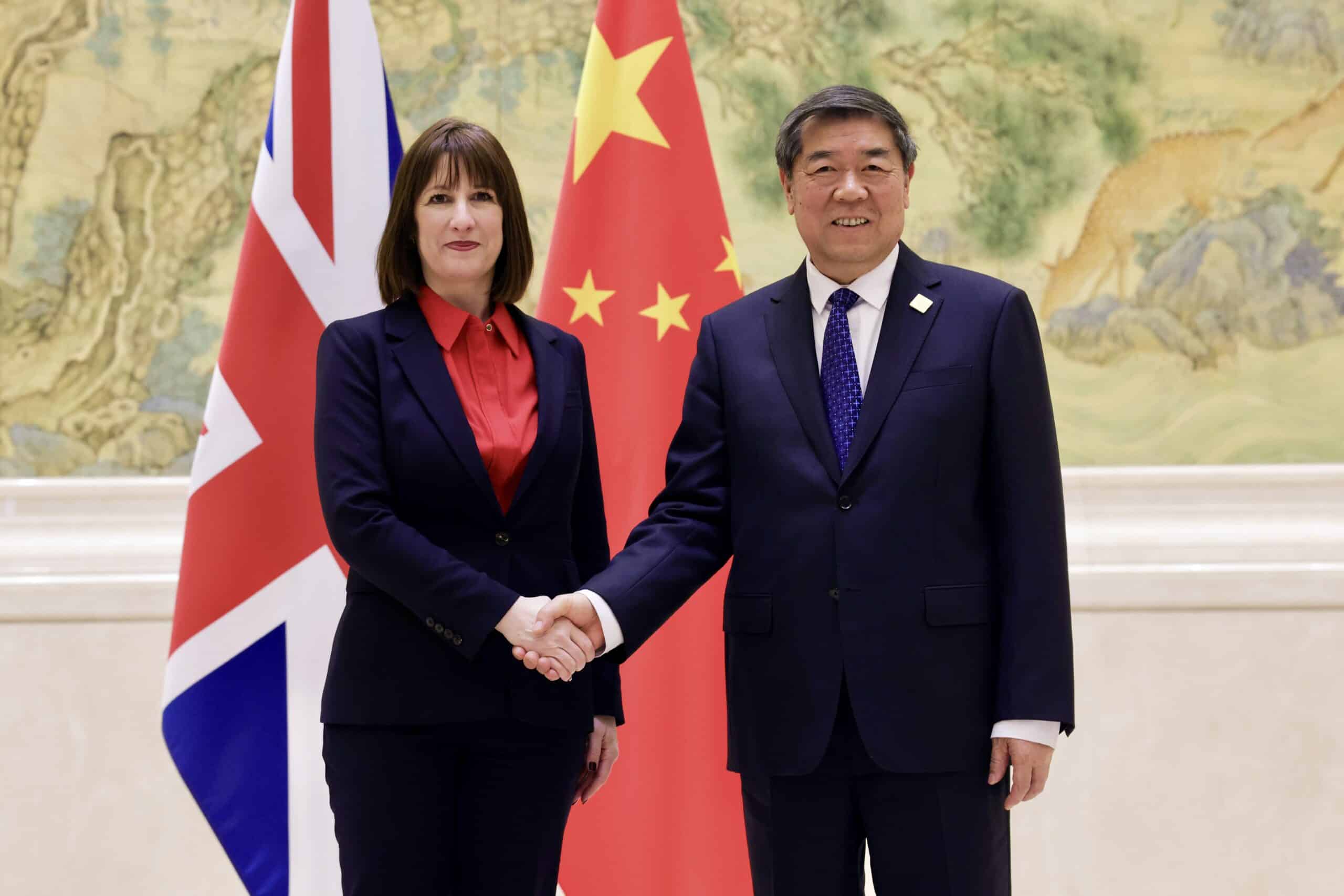

The current Labour government, led by Keir Starmer, has undertaken a so-called ‘China Audit’ which, in its topline conclusions revealed in June this year, made it abundantly clear that the default for the UK’s relations with Beijing would be engagement, except in cases where there were clearly understood disagreements. This would be a strange approach to take with a power labelled an enemy.

The China hawks in Britain — in politics, the security services, and elsewhere — get plenty of attention from bigging up potential threats that emanate from Beijing. To them, every Confucius Institute is a sleeper cell for civil unrest, and even the act of visiting China is akin to a sign of disloyalty and treachery.

But such a scattergun approach is as damaging as being complacent and pretending there are no problems whatsoever. The logic of stating China is an enemy state would mean cutting Britain off from economic opportunities that matter to our prosperity, and being involved in critically important engagements with new Chinese research and development on health, climate and the environment which are only going to matter more in the years ahead.

China is already the UK’s second largest collaborator by joint publications. According to British government data, there are over 800 projects ongoing, with £400 million matched funding on the UK and Chinese side, spread across 3500 research institutions. Sichuan University and Oxford University established a cancer research collaboration in 2020, one of many similar examples of both countries working deeply on combating common human challenges.

If there is one thing this case has proved it is that the current framework is no longer fit for purpose. It might be that the new National Security Law does provide improvements — but in the case of China, it has yet to be put to the test.

It is not in Britain’s national interests to block off possibilities that might arise from Chinese innovation and knowledge production like these in an era where, with a speed and scale that few predicted, China is now becoming a major technology player and an R&D powerhouse.

If the prosecution case against Messrs Cash and Berry did hinge on proving China was an enemy state, that would have involved legal and definitional issues, which the Crown Prosecution Service clearly — and in my view rightly — regarded as unlikely to be set out with the level of clarity and unambiguity necessary to secure a conviction. Sceptics might continue to insist that it was politics that played the main role in the dropping of this case, but the legal barriers look pretty formidable.

For the UK, there now needs to be much greater clarity on spelling out at least the principles on which one can decide what constitutes matters that should or should not be shared with a partner like China.

China is a complex partner, one that is posing uniquely difficult questions. If there is one thing this case has proved it is that the current framework is no longer fit for purpose. It might be that the new National Security Law does provide improvements — but in the case of China, it has yet to be put to the test. Let’s hope when and if that happens, there is far greater clarity around cases like the one we have just witnessed.

Kerry Brown is the Professor of Chinese Studies and Director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London. He is the author of The Great Reversal, a history of UK-China relations, among several other China-related books.