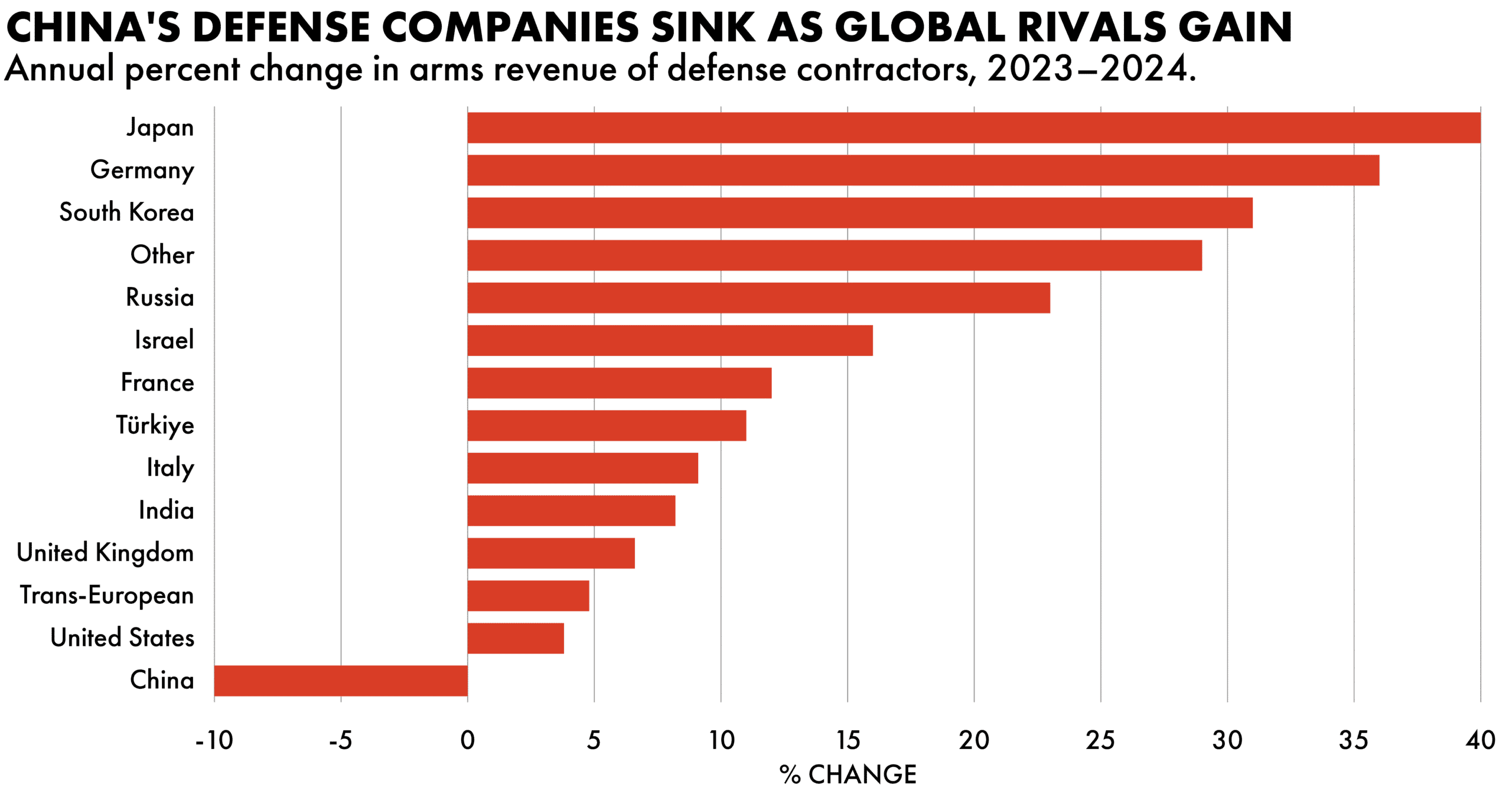

China has spent years building itself into a player in the global weapons industry. Those efforts are beginning to stall.

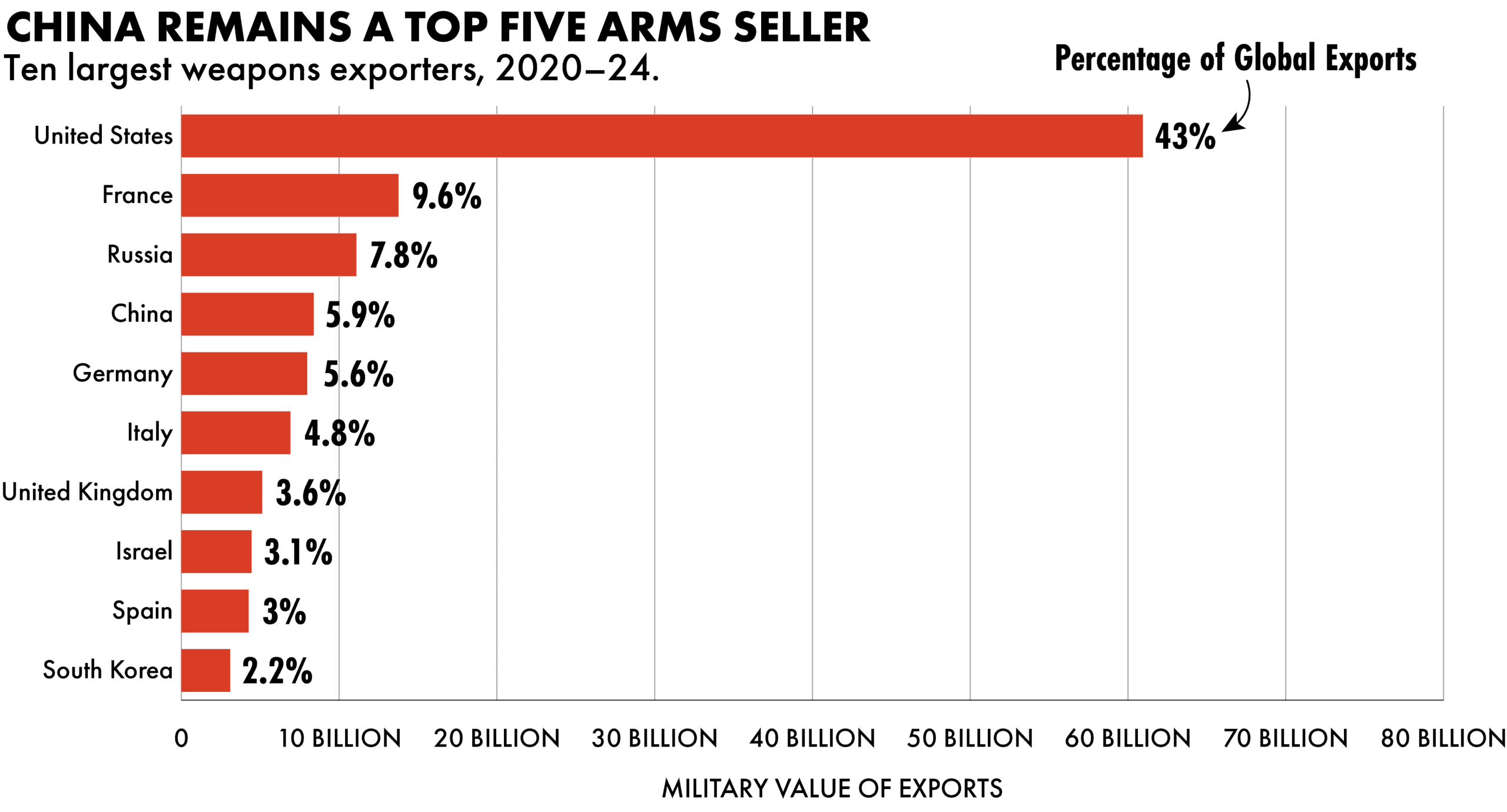

The eight Chinese defense companies tracked by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute recorded a 10 percent decline in their combined annual revenue in 2024, the most recent year with data available. Arms exporting companies in the rest of the world meanwhile saw their sales increase as wars continued to rage in Ukraine, Gaza and elsewhere, with total global arms exports reaching $679 billion, SIPRI data shows.

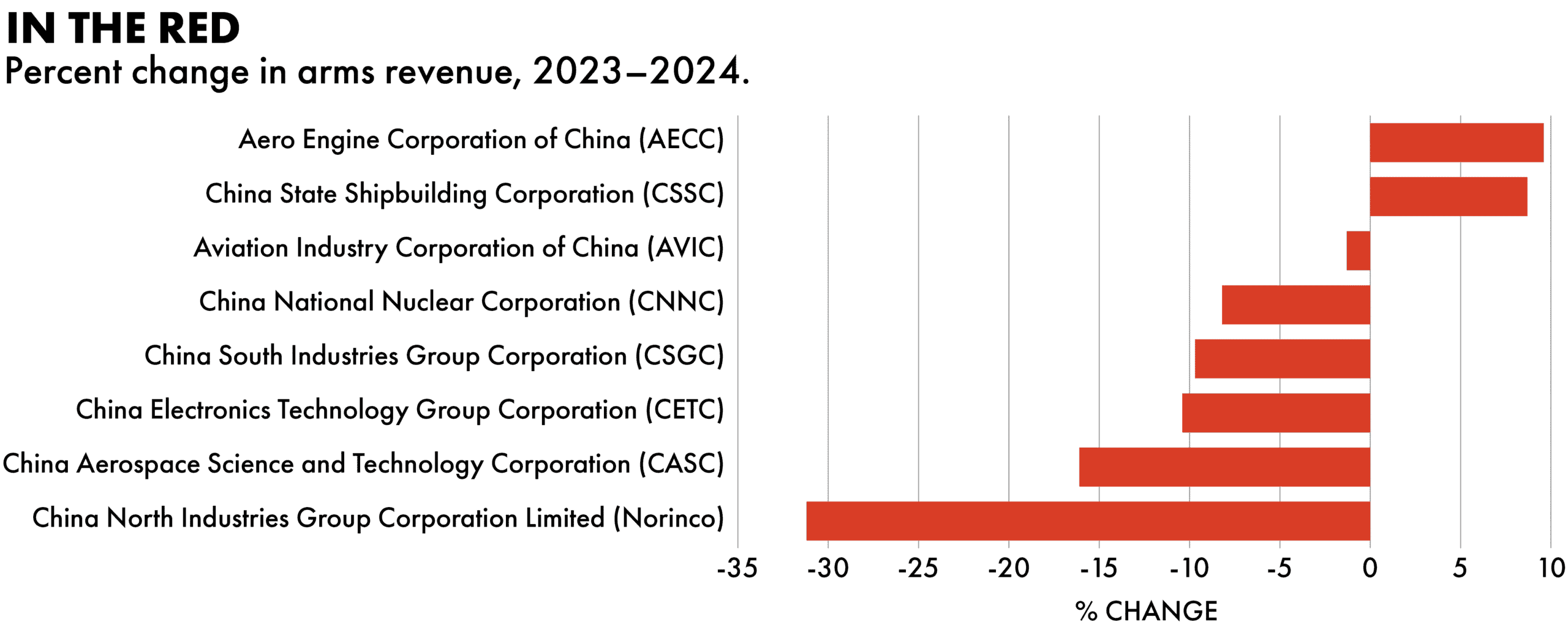

Excluding 2020, when arms sales sagged globally, the military value of China’s total weapons exports in 2024 was lower than in any year since 2009, according to SIPRI calculations. Only two of the eight Chinese firms it tracks saw yearly arms revenue increases in 2024; Norinco’s revenue from arms sales fell more than any other company’s, dropping 31.2 percent year-on-year.

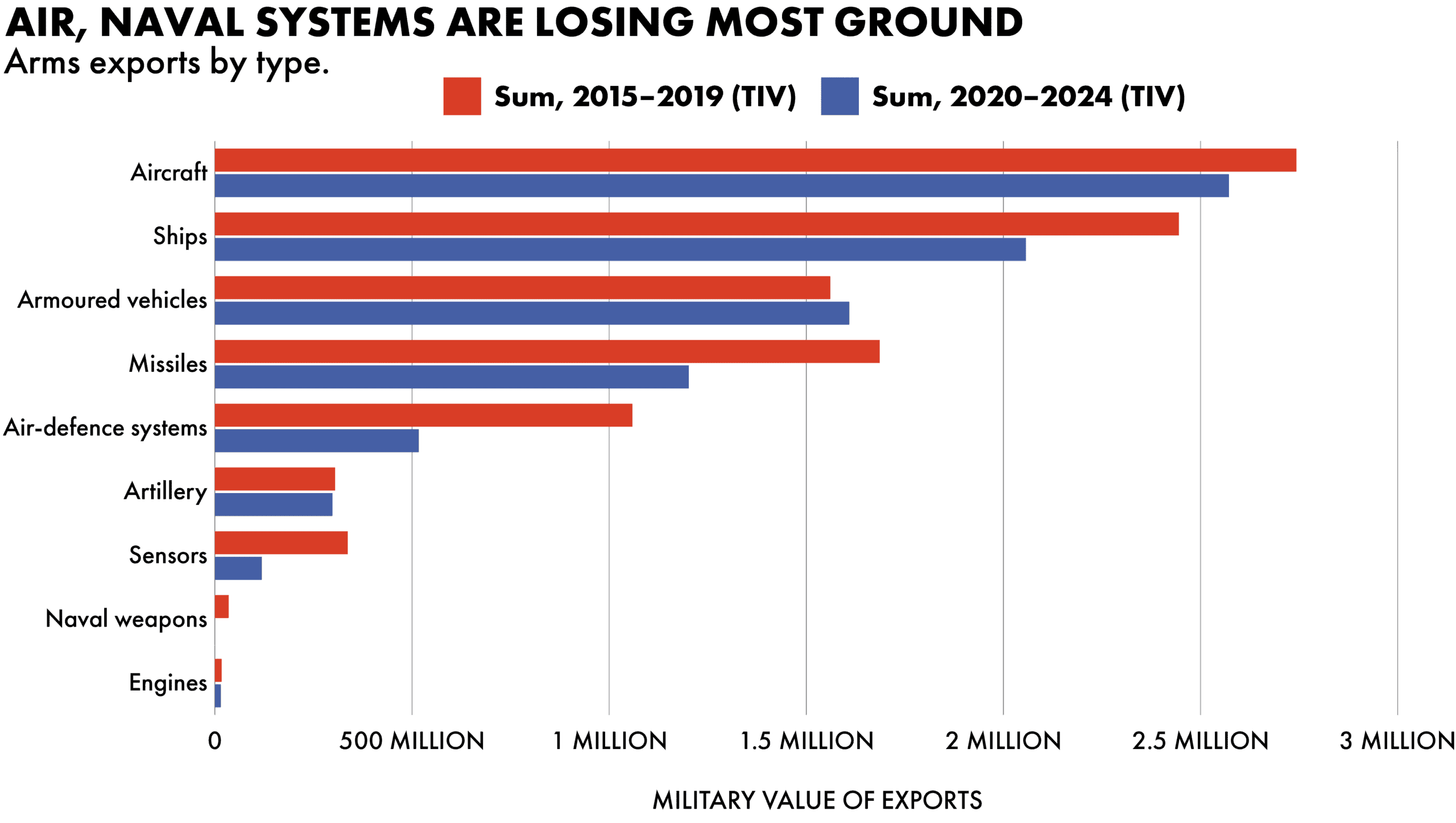

While 2024 could have been an outlier, there is some evidence of a persistent trend. The value of China’s total arms exports between 2020 and 2024 fell 5.4 percent relative to 2015–19, according to SIPRI. The nonprofit estimates that China’s defense spending has meanwhile increased from $258 billion in 2020 to $314 billion in 2024.

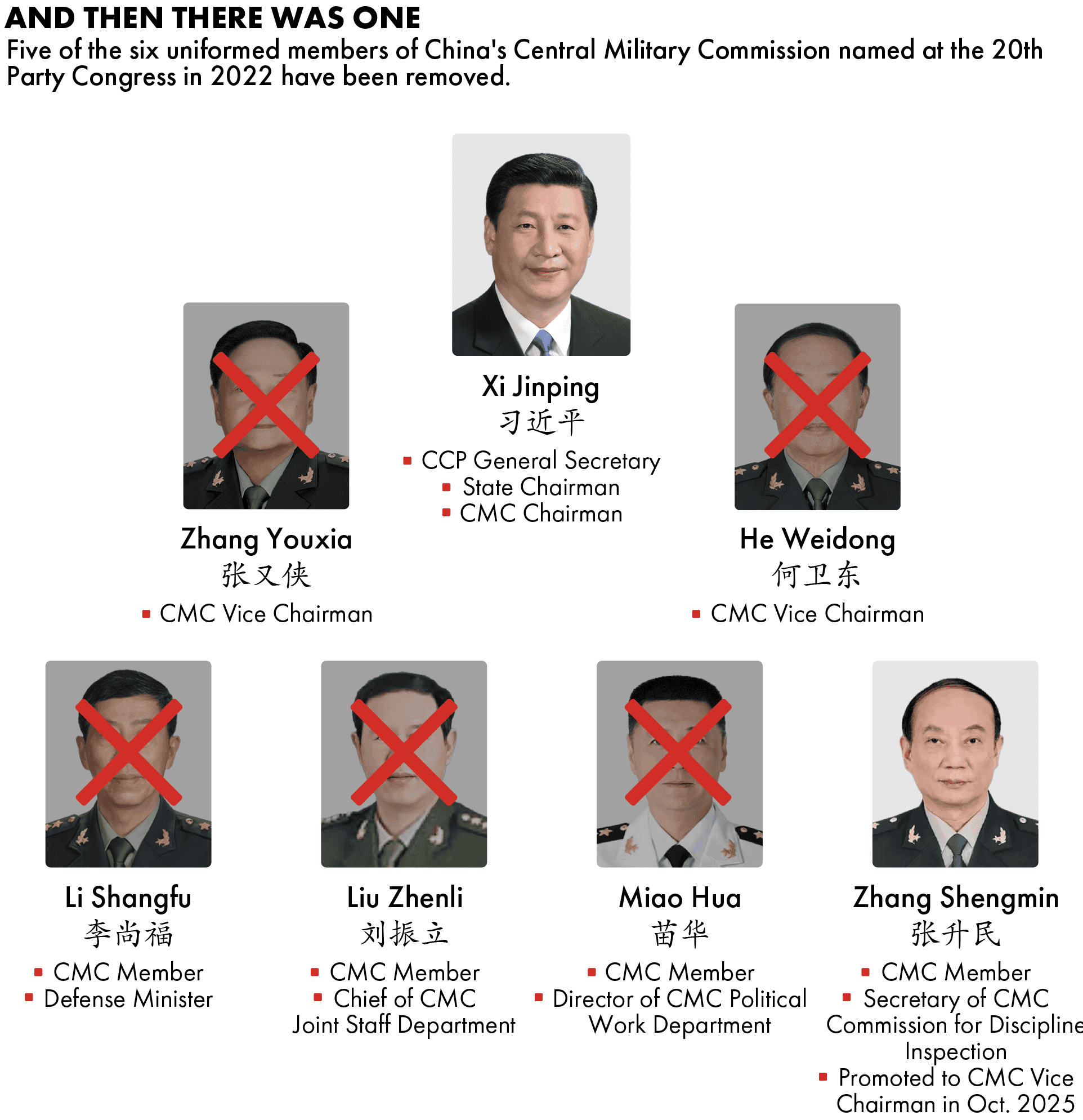

The decline comes as Xi Jinping purges top military officials, including executives at defense contractors. The chairmen of state-owned firms Norinco and China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) were both stripped of their political titles in China’s main political advisory body in 2023, according to state media outlet Xinhua, and later replaced in their roles.

Anti-corruption probes are “making the entire bureaucracy more careful,” says Shanshan Mei, a political scientist at the RAND Corporation. Another factor for the sales slowdown, she adds, may be that Beijing does not want the publicity of weapons exports, given President Xi Jinping’s “effort to frame China as a stabilizing and peace-promoting power.”

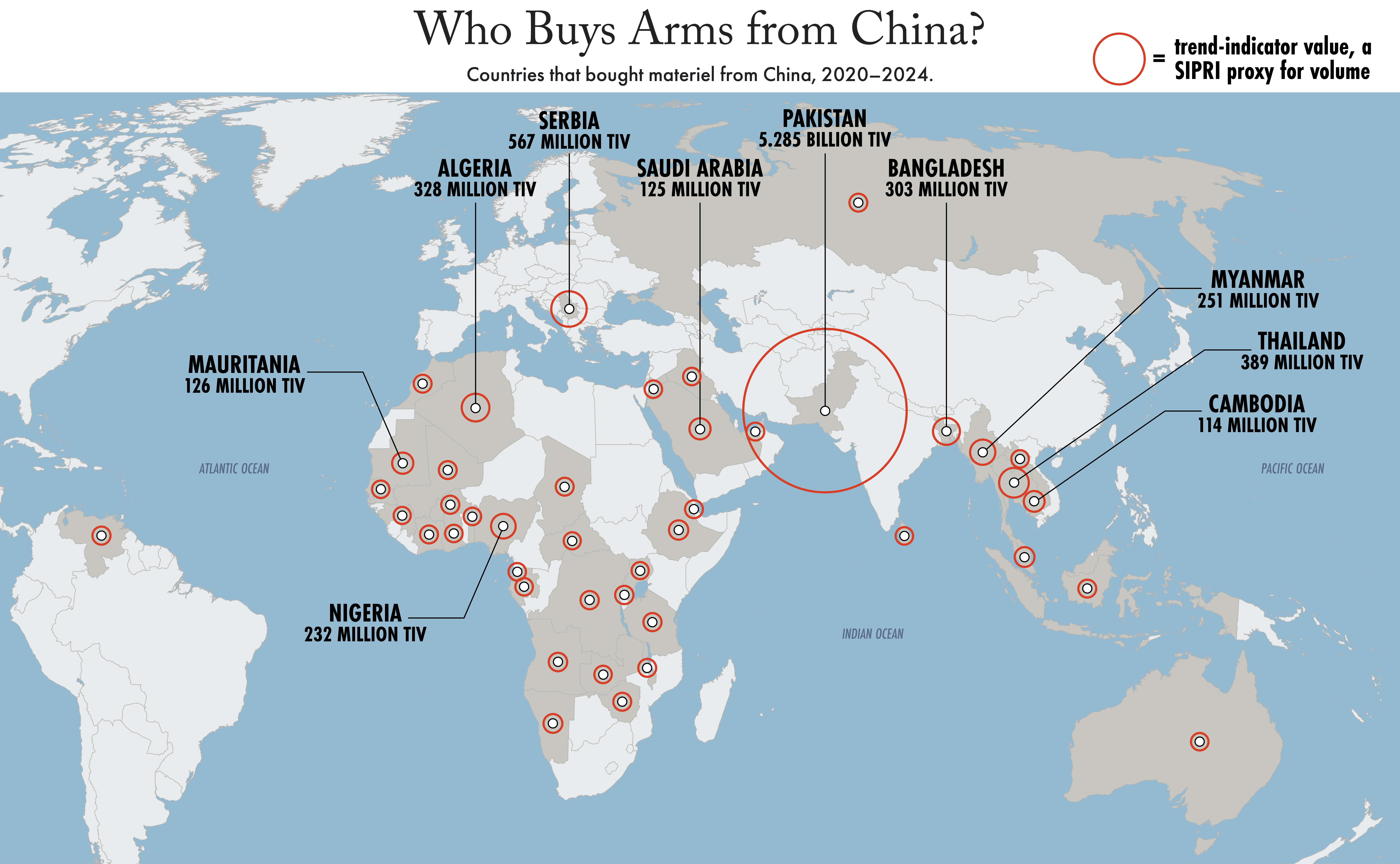

China has sold weapons to both Cambodia and Thailand, Mei notes, which have been engaged in an intermittent border conflict over the past year. But it still publicized a peace summit it held for the countries last December at a lake in Yunnan province. China has “been trying very hard to be the peacemaker, despite the fact that both countries have a history of buying Chinese weapons. It’s the ultimate irony.”

While there may be a dip in 2024, we shouldn’t write off China as one of the world’s major arms exporters. They still offer relatively cheap, increasingly sophisticated weaponry to markets that may not have good alternatives.

Bates Gill, an expert on Indo-Pacific security at the National Bureau of Asian Research

Beijing also has the problem of being too reliant on a single customer. Pakistan accounted for 63 percent of China’s weapons exports between 2020 and 2024, according to SIPRI, and bought more than two-thirds less arms in 2024 as it did in 2023.

“Perhaps China has reached a bit of a peak in terms of its recipient markets,” says Bates Gill, an expert on Indo-Pacific security at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

Still, China’s weapons sales are large enough to place it in the upper ranks of global weapons sellers. Gill, who was formerly SIPRI’s director, expects that it will remain there.

“While there may be a dip in 2024, we shouldn’t write off China as one of the world’s major arms exporters,” he says. “They still offer relatively cheap, increasingly sophisticated weaponry to markets that may not have good alternatives.”

Noah Berman is a staff writer for The Wire based in New York. He previously wrote about economics and technology at the Council on Foreign Relations. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe and PBS News. He graduated from Georgetown University.